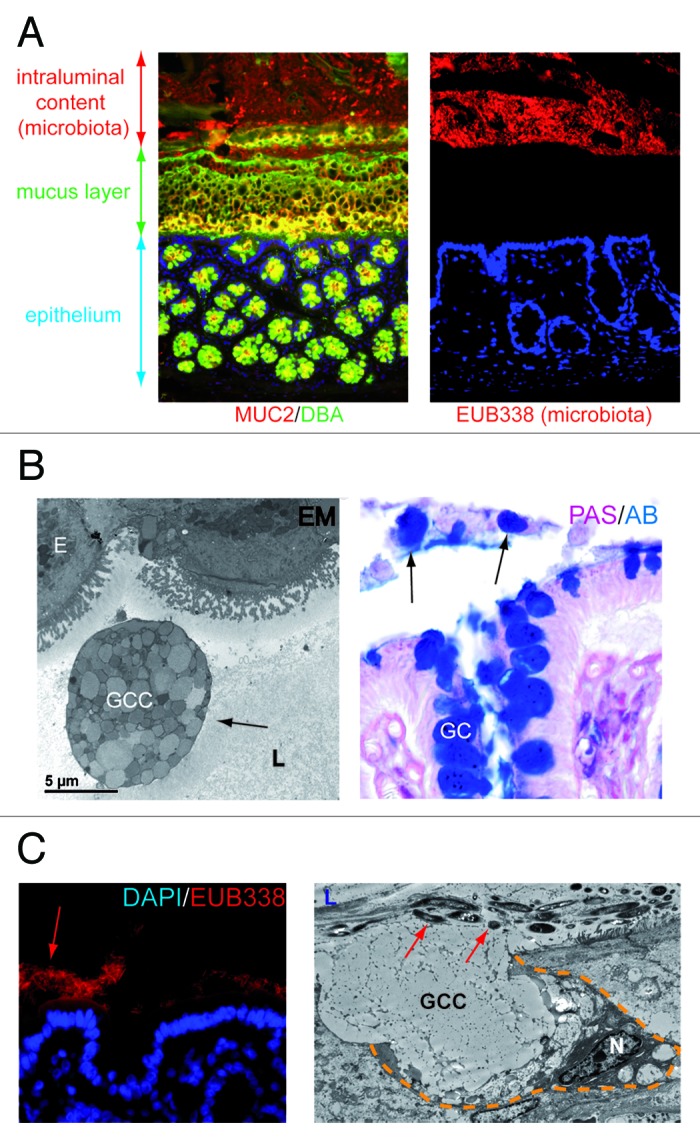

Figure 1.(A) The colonic mucus layer provides a physical barrier between intraluminal microbiota and the colonic epithelium. Left panel: immunofluorescent staining of healthy rat colon. Healthy mucus is composed of highly glycosylated MUC2 (MUC2, red; Dolichus Biflorus Agglutinin (DBA), green; overlay, yellow). Right panel: the mucus layer provides a physical barrier preventing interaction of intraluminal bacteria (stained in red, EUB388 stains rDNA of bacteria) with the colonic epithelial cells (blue, nuclei of the cells in the colonic mucosa). (B) Goblet cells are released into the gut lumen upon colonic ischemia. Electron microscopy picture (left panel) and PAS/AB staining (right panel) of human colon exposed to ischemia. Note the presence of entire goblet cell contents in the colonic lumen (arrows), which might indicate impaired dissemination of goblet cell granules. (E, epithelial cell; GC, Goblet cell; GCC, Goblet cell contents; L, lumen) (C) Loss of the mucus layer allows physical interaction of bacteria with epithelial cells which triggers goblet cell mucus release. Left panel: fluorescent in situ hybridization with EUB388, which stains rDNA of bacteria, shows intraluminal bacteria in close proximity with the colonic epithelium in rat colon exposed to ischemia. Right panel: Electron microscopy reveals that goblet cells release their contents (GCC, goblet cell contents) into the crypt lumen (L) upon IR in an attempt to flush bacteria (red arrows) from the crypts. (N, nucleus; yellow dashed line demarcates a goblet cell).