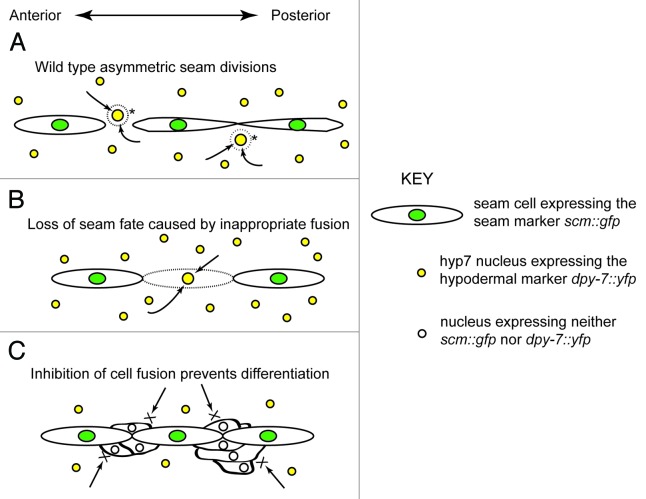

Figure 1.

The role of seam cell contacts and boundaries in maintaining the stem-like fate. (A) During asymmetric seam cell divisions, anterior daughters (marked by asterisks) leave the line of the seam and lose expression of scm::gfp (green shading). Breakdown of the cell membrane likely allows differentiation signals from the surrounding hypodermis (arrows) to enter the cells, which consequently switch on expression of the hypodermal marker, dpy-7::yfp (yellow shading). In this diagram, the two posterior-most seam cells have already joined up after the division. This contact is essential for subsequent divisions of the seam; maintenance of the correct (i.e., end-to-end) cell contacts is required for propagation of the stem fate. (B) In animals subjected to knockdown of ajm-1, dlg-1, elt-1 or let-413 by RNAi, inappropriate loss of cell membranes is observed (dashed line). As in (A), dissolution of the membrane surrounding seam cells may facilitate the entry of differentiation signals from the hypodermis, resulting in affected seam cells making the transition from the stem to the differentiated fate. (C) In eff-1 mutants the anterior daughters of seam divisions fail to fuse with the hypodermal syncytium. These cells leave the line of the seam, accumulating alongside the lineage. They cease dividing and most lose scm::gfp expression. They are, however, unable to differentiate–DPY-7::YFP is never observed–and thus are in what we term a state of “developmental limbo.” According to our model, the differentiation signals from the hypodermis (arrows, as in A and B), which would normally enter these cells as the membrane breaks down, are prevented from doing so. As a result, differentiation does not occur; the membrane effectively acts as a protective niche, shielding the seam from the influence of the surrounding hypodermis.