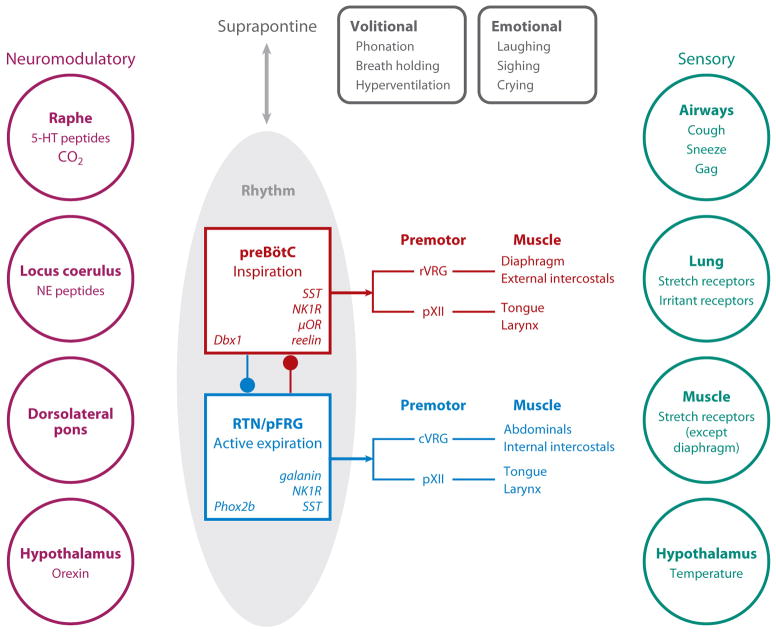

Figure 1. Overview of the central pattern generator for breathing.

Core rhythm generating circuits appear to have two distinct brainstem oscillators, the endogenously active preBötC (red box) driving inspiratory activity by projections to various premotor populations that in turn project to inspiratory muscles that pump air, e.g., diaphragm and external intercostals, and those that modulate airflow resistance, e.g., laryngeal and tongue muscles, and the conditionally active RTN/pFRG (blue box) that have a similar functional path to expiratory muscles. There are numerous influences: i) Neuromodulatory (left). Respiratory pattern is highly labile. When you go from quiet sitting to slow walking, your O2 consumption increases ~3-fold, and if your ventilation does not increase rapidly you probably will pass out within 100 meters. There is widespread agreement that peptides, serotonin, norepinephrine and other endogenous neuromodulators can affect rhythmogenesis (Garcia et al 2011). These actions are essential for normal regulation and may go awry in diseases affecting breathing. ii) Suprapontine inputs (top) related to volition and emotion. iii) Sensory inputs (right) essential for proper regulation of blood gases and for mechanical adjustments related to posture, body mechanics and likely metabolic efficiency. This review focuses on the core oscillators.