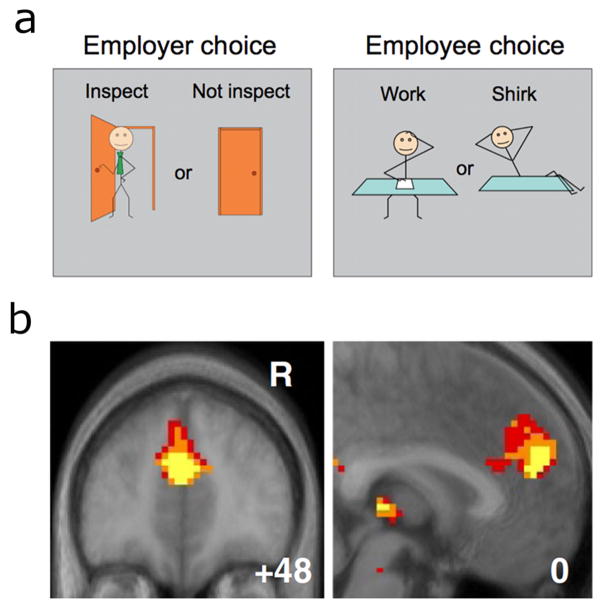

Figure 2.

Strategic game used by Hampton et al. [17]. (a) In this task, one participant acted as an “employer” and the other as an “employee”. Each player could perform one of two actions: the employer could “inspect” or “not inspect” her employee while the employee could “work” or “shirk”. The interests of the two players are divergent in that the employee prefers to shirk, while the employer would prefer the employee to work, and the employer would prefer to not inspect her employer than to inspect – yet for an employee it is disadvantageous to be caught shirking if the employer inspects, and disadvantageous for the employer if the employee shirks while she doesn’t inspect. (b) In such a context it is crucial to form an accurate prediction of an opponent’s next action. This could involve simply tracking the probability with which they choose each of the two strategies available to them. However, if an opponent is tracking ones own actions in this way, then it is advantageous for a player to update their prediction of their opponent’s action to incorporate the effect of the player’s own previous action on their opponent. Hampton et al. found that the effect of this update at mPFC (−3, 51, 24 mm) was modulated by the model-predicted degree to which a subject behaves as if his actions influence his opponent.