Abstract

Using a high throughput screen, we have identified a family of 12-residue long peptides that spontaneously translocate across membranes. These peptides function by a poorly understood mechanism that is very different from that of the well-known, highly cationic cell penetrating peptides such as the tat peptide from HIV. The newly discovered translocating peptides can carry polar cargoes across synthetic bilayers and across cellular membranes quickly and spontaneously without disrupting the membrane. Here we report on the biophysical characterization of a representative translocating peptide from the selected family, TP2, as well as a negative control peptide, ONEG, from the same library. We measured the binding of the two peptides to lipid bilayers, their secondary structure propensities, their dispositions in bilayers by neutron diffraction, and the response of the bilayer to the peptides. Compared to the negative control, TP2 has a greater propensity for membrane partitioning, although it still binds only weakly, and a higher propensity for secondary structure. Perhaps most revealing, TP2 has the ability to penetrate deep into the bilayer without causing significant bilayer perturbations, a property that may help explain its ability to translocate without bilayer permeabilization.

Introduction

The permeability barrier imposed by the lipid bilayer membrane is one of the essential requirements for life. However, this barrier also prevents the cellular entry of polar compounds that could be beneficial in the laboratory or in the clinic. There are many classes of potentially useful, but not membrane-permeable, compounds including drug-like small molecules, metabolite analogs, peptides, proteins, imaging agents, small RNAs, DNA, and nanoparticles, but currently there are few, if any, efficient nonperturbing methods of delivering such compounds into cells. Some of the existing methods that are used for this purpose are based on the physical disruption of the membrane. These include electroporation (1), detergent-like disruption (e.g., lipidic transfection reagents) (2), lipid vesicle fusion (3), use of pore-forming peptides (4), and use of membrane-permeabilizing proteins (5). These methods all have significant drawbacks, including low efficiency, toxicity, and disruption of cell physiology. Furthermore, few of these methods, if any, can be used in vivo. The other major category of techniques for delivery of polar compounds into cells are those that take advantage of existing cellular pathways. If properly targeted to a cellular pathway, polar compounds can enter cells via endocytosis, pinocytosis, or phagocytosis (6,7). These approaches can theoretically be used in vivo; however, they also have low efficiency, mainly because of inefficient release from the endosomal pathways (6).

A polypeptide sequence that can translocate spontaneously across membranes with an attached polar cargo would have advantages over the methods that are available to deliver polar compounds into living cells. For this reason, we have, to our knowledge, taken a new approach to discover novel spontaneous membrane-translocating peptides using combinatorial peptide libraries and orthogonal high throughput screens (8). By using an orthogonal screen that simultaneously assays for peptide-induced membrane permeabilization and for spontaneous peptide translocation across bilayers, we identified a family of translocating peptides from a rational 10,384-member peptide library (8). These 12-residue peptides, which have a conserved LRLLR sequence motif, cross synthetic lipid bilayers and cellular membranes quickly (rate > 0.1 s−1), even when attached to non-membrane-permeable cargoes. Translocation into cells is spontaneous and is independent of cellular energy-dependent processes such as endocytosis, allowing delivery of polar cargoes directly to the cytoplasm without toxicity (8). Thus, the spontaneous membrane-translocating peptides are very different from the highly cationic cell-penetrating peptides such as the tat peptide from the HIV Tat protein, which enters cells via endocytosis and is localized predominantly in endocytic compartments, and not the cytoplasm (6,8). Because of this, the cargo delivery capabilities of the two peptide classes are also different, with the cell-penetrating peptides being able to carry much larger cargo, but mainly to endocytic compartments. On the other hand, the spontaneously translocating peptides can deliver cargo up to 1000 Da directly across the plasma membrane (unpublished results).

Whereas the membrane translocation and cargo delivery capabilities of the identified peptides are now well established (8), the details of their interactions with lipid membranes and the mechanism of translocation are not known. This is a roadblock to their optimization and widespread utilization. Here we report on the first biophysical characterization of these peptides in membranes, to our knowledge. We investigate one membrane-translocating peptide, TP2, as well as an observed nontranslocating peptide from the same peptide library, ONEG, that is used here as a negative control. We measure the binding of the two peptides to bilayers, their secondary structures, their dispositions in the bilayers, and the response of the bilayers to the peptides. Our results demonstrate that the translocating peptide has the ability to penetrate deep into the bilayer without causing significant bilayer perturbations.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and peptides

POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) and DPPE-PEG2K (1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-n-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000]) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). The sequences of the peptides investigated here, TP2 and ONEG, are shown in Fig. 1. The peptides were synthesized and purified by Bio-Synthesis, Inc. (Lewisville, TX). For the neutron diffraction experiments, peptides were synthesized with deuterated leucines and glycines as indicated in Fig. 1. The deuterated amino acids were from C/D/N Isotopes (Pointe Claire, Québec, Canada).

Figure 1.

Amino-acid sequences of the translocating peptide TP2 and the inactive control ONEG. The amino acids that were deuterated for the neutron diffraction experiments are shown in bold and underlined.

Binding measurements

The mole fraction partition coefficients describing peptide binding to POPC large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) were measured using equilibrium dialysis (9). In this assay, a semipermeable membrane separates two compartments, with LUVs added to only one of them. The peptide is added to either compartment and allowed to equilibrate such that the aqueous concentration of the free peptide becomes the same in the two compartments. In addition to free peptide, the compartment with the LUVs also contains the bound peptide. Because the semipermeable membrane allows passage and equilibration of peptides but not vesicles, measurements of the total peptide concentration in the two chambers yield the free, [P]w, and the free+bound, [P]w + [P]b, peptide concentrations. These peptide concentrations were determined using HPLC as described previously by Wimley and co-workers (10–12). Mole fraction partition coefficients were calculated as

| (1) |

where [L] and [W] are the molar concentrations of lipid and water.

The mole fraction partition coefficients were measured here in the presence of 10, 50, and 100 mM POPC. The partition coefficients can be used to calculate the fraction of peptide bound (fb), at any lipid concentration [L], using the following equation:

| (2) |

Circular dichroism

Circular dichroism (CD) is a technique that reports on the secondary structure of proteins (13–16). The CD spectra were collected using a model No. 810 spectropolarimeter (JASCO, Easton, MD). Samples were placed in a 1-mm path-length quartz cuvette at room temperature. At least three spectra were collected at a scan rate of 10 nm/min, and averaged. After subtraction of background, the mean residue ellipticity was calculated using the peptide concentration.

Oriented CD

Oriented CD (OCD) can provide information about the secondary structure of peptides embedded into multibilayer samples (17–20). Multilayer samples containing 5 mol % peptides were prepared by dissolving the peptides in methanol and POPC in chloroform (21,22). The two solutions were mixed in the appropriate ratios, and a multibilayer sample was prepared by applying the solution dropwise on a quartz slide. After solvent evaporation, the slide was placed perpendicular to the beam in a custom-designed chamber as described previously (18,19,23–25). To hydrate at 76% relative humidity (RH), a drop of saturated NaCl solution was placed in the chamber and the sample was equilibrated (25,26). Eight spectra were recorded while rotating the sample holder around the beam axis in increments of 45°. These spectra were averaged and then corrected for lipid background as described by Hristova and co-workers (25,26).

Neutron diffraction experiments: data collection and analysis

Neutron diffraction is a useful technique that yields information about the structure of lipid bilayers and the disposition of membrane-bound peptides (27–34). The neutron diffraction experiments were performed at the Advanced Neutron Diffractometer/Reflectometer at the National Institute of Standards and Technology Center for Neutron Research, Gaithersburg, MD (35).

The samples were prepared similarly to the samples used in the OCD experiments. The samples consisted of lipid bilayer stacks aligned along the surface of a solid support. The oriented multilayer samples, ∼5-μm thick, were prepared as dry lipid films spread over an area of ∼1.5 × 1.5 cm2 on thin glass slides, and hydrated from the vapor phase of a saturated salt solution. A relative humidity of 76% was maintained throughout the experiments by using containers with saturated NaCl solution placed next to the sample in a sealed aluminum chamber. Diffraction data were collected by rotating the average lipid bilayer plane through the angle Θ, and detecting the diffracted beam at angle 2Θ, relative to the beam direction. This configuration was chosen to ensure that the momentum transfer between the incident and diffracted neutron wave vectors was always perpendicular to the multilayer plane, thus probing the density distribution along the bilayer normal. Several (Θ–2Θ) scans were collected, monitoring changes in the diffraction pattern as the sample equilibrated. Only data collected after full sample equilibration were used for determining the bilayer density profile.

The sample was exposed to a neutron beam of wavelength 5 Å, and the intensity of the diffracted beam was recorded using a He-3 gas-filled 25.4-mm-wide pencil detector (GE/Reuter-Stokes, Twinsburg, OH) (36–38). Initial data processing was performed using the software package REFLRED, developed at the National Institute of Standards and Technology Center for Neutron Research. Data analysis was performed with the commercially available software package ORIGIN (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). The observed structure factors were calculated as

| (3) |

where I(h) is the intensity of the hth peak, and Θ is the Bragg angle.

The peaks were integrated in the software ORIGIN using two different methods: numerical integration of the areas under the peaks (IA), or by fitting Gaussians to the diffraction peaks and integrating analytically (IG). The average of the two areas given by the two methods yielded I(h) as used in Eq. 1. The experimental uncertainties in the peak intensities were calculated as the square-root of the intensities (neutron counts). The difference between IG and IA was similar to the uncertainties calculated in this way.

Absolute scaling

The absolute scattering length density ρ*(z) is the scattering density per lipid molecule, given by (39)

| (4) |

where f(h) values are the measured structure factors on an arbitrary scale; is the instrumental constant; d is the Bragg spacing; ρ0* is the average scattering length density of the unit cell; and hobs is the highest observed diffraction order. are the absolute structure factors, which are determined solely by the structure and the scattering of the unit cell (26,40).

The instrumental constant and the absolute structure factors can be determined if diffraction patterns are recorded for two samples with isomorphous unit cells, i.e., identical except for a few atoms with large differences in scattering lengths (26,40,41). Here we compared structure factors for POPC bilayers containing hydrogenated and deuterated peptides (sequences shown in Fig. 1), as discussed below. Five mol % deuterated TP2 and ONEG introduced 2.47 and 1.52 deuterons per lipid, respectively, providing sufficient contrast to scale the structure factors.

The absolute structure factors F(h) were obtained from the experimentally determined structure factors f(h) by calculating the instrumental constants k(h), as well as the width and the position of the deuterated amino acids within the thickness of the bilayer, AD and ZD, according to

| (5) |

| (6) |

Here bD is the neutron scattering length difference due to the hydrogen/deuterium substitution in the peptides (scattering length for hydrogen is −0.3739 × 10−12 cm and for deuterium is 0.6671 × 10−12 cm). Four orders of diffraction were recorded in all experiments, i.e., hobs = 4. The system of four expressions in Eq. 5 was used to calculate the four unknown parameters for TP2:

The set of expressions in Eq. 6 was used to determine the four unknown parameters for ONEG:

The absolute structure factors were calculated using the following equations:

| (7) |

Leakage of ANTS and DPX from POPC vesicles

We measured the peptide-induced leakage of the fluorophore/quencher pair ANTS/DPX from POPC vesicles as described in Ellens et al. (42) and Hristova et al. (43,44). Unilamellar vesicles of 0.1-μm diameter were made by extrusion of multilamellar vesicles through a polycarbonate filter with 0.1-μm diameter pores (Nucleopore; Millipore, Billerica, MA) (42–44). Unencapsulated ANTS and DPX were removed with gel filtration. In leakage experiments, ANTS fluorescence of 1 mM solution of ANTS/DPX-containing vesicles was measured as a function of time, before and after the addition of peptides at different concentration. The fluorescence for 100% leakage was determined by the addition of 0.4 vol % (v/v) of the detergent Triton X-100, which causes vesicle solubilization. Fluorescence was measured with a Fluorolog spectrophotometer from Horiba Jobin Yvon (Edison, NJ) using excitation and emission wavelengths of 355 nm (slit 2.5 nm) and 520 nm (slit 2.5 nm), respectively. The contribution of light scattering was negligible under these conditions.

Supported bilayers and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

Previously we have characterized the response of asymmetric, diphytanoyl PC-containing bilayers to TP2 and ONEG (45). To make a direct comparison using a variety of techniques for POPC bilayers, we performed a new set of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) experiments in POPC. As described in detail in Lin et al. (46), we prepared polymer-cushioned, surface-supported POPC bilayers on silicon by Langmuir-Blodgett deposition of monolayers composed of POPC and 5.9 mol % DPPE-PEG2K, followed by fusion of 0.1-μm unilamellar POPC vesicles. The support was highly doped n-silicon (47), cleaned with consecutive washes of IPA, acetone, IPA, and a Piranha etch solution (34% hydrogen peroxide, 66% sulfuric acid). A 1 mg/mL chloroform solution of POPC with 5.9 mol % DPPE-PEG2K was deposited onto the surface of a Langmuir-Blodgett trough (KSV NIMA, Biolin Scientific, Linthicum Heights, MD). After solvent evaporation, the monolayer was compressed to 32 mN/m. Deposition of the POPC/DPPE-PEG2K monolayer on the silicon wafer was accomplished by withdrawing the silicon from the buffer through the monolayer at a speed of 15 mm/s, while maintaining constant surface pressure. Next, a Teflon electrochemical cell was sealed to the surface of the silicon and 450 μL of a 1.3-mM solution of POPC unilamellar vesicles was added to the cell. Incubation for 1 h allowed for a surface-supported bilayer to form by vesicle fusion. After that, 10 mL phosphate buffer containing 100 mM KCl was added to the cell, bringing the vesicle concentration to 60 μM and the bilayer was allowed to equilibrate for 24 h before measurements.

An Ag/AgCl reference electrode and a Pt counter electrode were placed in contact with the buffer solution, and a ground connection was made to the silicon (46). The impedance spectra were measured across the frequency range from 105 to 1 Hz with a DC bias voltage of zero. In each experiment, the impedance of the bilayer was first measured, and then the peptide was added to the vesicle solution in the chamber (48,49) such that the overall peptide/lipid was defined. After peptide addition, the impedance response was measured every 2 min continuously for 1 h. The impedance response was analyzed by fitting the measured response to an ideal RC circuit as described in Lin et al. (47).

Results

Binding of TP2 and ONEG to POPC bilayers

We measured the mole fraction partition coefficients for TP2 and ONEG, using equilibrium dialysis as described in Materials and Methods and White et al. (9). Briefly, we used HPLC to measure the concentrations of free and bound peptides at equilibrium in the presence of POPC vesicles at lipid concentrations of 10, 50, and 100 mM (the range over which binding was experimentally measurable). The calculated mole fraction partition coefficients are shown in Table 1. The averages of all experiments are KTP2 = 3200 ± 800 and KONEG = 190 ± 10. Importantly, the partition coefficients were independent of the lipid concentration over the measurable range. This finding suggests that binding is not influenced by peptide self-association in the membrane, as has been observed for other families of peptides (50). Thus, the peptides likely partition into the bilayer as monomers. The measured partition coefficients can therefore be converted to fraction of peptide bound for any lipid concentrations, such as in the CD experiments described below, using Eq. 2.

Table 1.

Binding of TP2 and ONEG to POPC large unilamellar vesicles measured by equilibrium dialysis

| Lipid (mM) | TP2 |

ONEG |

|---|---|---|

| Partition coefficient | ||

| 10 | 3600 ± 500 | 180 ± 6 |

| 50 | 2300 ± 500 | 210 ± 6 |

| 100 | 3900 ± 500 | 200 ± 6 |

| Average | 3200 ± 800 | 190 ± 10 |

The uncertainties are standard errors.

The weak, but measurable binding of TP2 is consistent with its observed membrane translocation. We previously estimated the rate of translocation of TP2-TAMRA across a bilayer to be between 0.1 and 1 s−1 by assuming that 10% of the peptide was bound (8). Based on the data presented here, we calculate that ∼5% of TP2 is bound at 1 mM POPC so the previous estimate of translocation rate must be close to the true value. In the presence of cells or lipid vesicles, there is a small, but nonnegligible steady-state population of bound peptide. This bound peptide, coupled with an inherently high rate of translocation, is sufficient to explain the observed behavior of TP2.

Peptide secondary structure

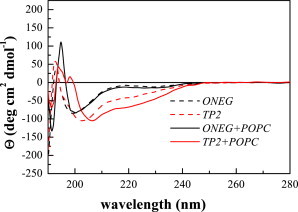

The CD spectra of the two peptides in phosphate buffer at pH 7 are shown in Fig. 2. ONEG is unstructured in buffer, as evident from the minimum at 200 nm which is indicative of a random coil. TP2 is also mostly random coil in buffer, but the shallow minimum at 210–220 nm suggests that there may be a small amount of unidentifiable secondary structure.

Figure 2.

CD spectra of 100 μM TP2 and ONEG in buffer and in the presence of 5 mM POPC liposomes. In both samples, TP2 has more secondary structure.

Fig. 2 also shows the CD spectra in the presence of 5 mM LUVs. There is no change in the signal for ONEG, with the minimum remaining at ∼200 nm. However, from the binding measurements, we calculate that only ∼2% of the peptide is bound to the vesicles at this lipid concentration, and thus the contribution of bound ONEG to the CD spectrum is small and we cannot conclude whether or not ONEG is structured in membranes from this experiment. The TP2 spectrum changes slightly in the presence of vesicles. In this case, ∼20% of TP2 is bound to the vesicles. However, the change in the CD signal is small, and thus the exact secondary structure of bound TP2 cannot be determined from the spectra. We can conclude, however, that:

-

1.

TP2 is more structured than ONEG both in the absence and presence of vesicles; and

-

2.

The degree of TP2 secondary structure increases upon binding to membranes.

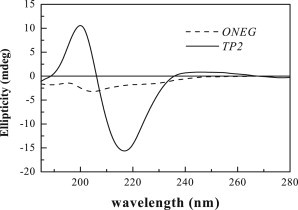

To better assess the differences in secondary structure propensity between TP2 and ONEG when they are associated with bilayers, we used oriented circular dichroism (OCD). In an OCD experiment, samples consist of oriented multibilayer stacks containing peptides (18–20). These samples are produced by aliquoting peptides and lipids, codissolved in methanol, onto a quartz disk, followed by solvent removal and hydration of the lipid/peptide film through the vapor phase. Although the oriented bilayers are in the fluid phase, there is no bulk aqueous phase for the peptides to explore. Therefore, all peptides are associated with the bilayer, at least interfacially. The concentration of both TP2 and ONEG in the bilayers are 5 mol %, as aliquoted. The OCD spectra are shown are Fig. 3, and they are distinctly different for the two peptides. The minimum at 200 nm observed for ONEG is indicative of a random coil, although the very low intensity may suggest the presence of some small amount of secondary structure. The OCD signal of TP2, on the other hand, shows a distinct single minimum at ∼215 nm indicative of an extended or β-sheet-like structure. We therefore conclude that the translocating peptide TP2 has a significantly higher propensity for secondary structure than the nontranslocating peptide ONEG. As the binding experiments suggest that no significant TP2 oligomerization occurs in the membrane, the structure of membrane-bound TP2 is not likely a β-sheet oligomer.

Figure 3.

OCD spectra of 5 mol % TP2 and ONEG in oriented multibilayers of POPC, equilibrated at 76% relative humidity in a sealed chamber through the vapor phase.

Peptide disposition in bilayers

We used neutron diffraction to assess the disposition of the two peptides in POPC bilayers. Samples for the neutron diffraction experiments, like the OCD samples, were stacked multilayer samples containing TP2 and ONEG, or their deuterated versions TP2-D and ONEG-D. The deuterated amino acids in TP2-D and ONEG-D are shown in bold in Fig. 1. The multilamellar samples were placed in the neutron beam and equilibrated at 76% RH. The thermal disorder in the structure is lower at 76% RH than at full hydration, which allowed us to observe four orders of diffraction in all experiments (a requirement for subsequent data analysis (26)). Just like in the OCD experiments, there is no bulk aqueous phase for the peptides to explore and the peptide concentration is 5 mol % in all cases.

The goal of these experiments was to measure the transbilayer distribution of the deuterium labels in bilayers containing either TP2 or ONEG. To compare the neutron scattering length density profiles of different samples, the profiles were scaled and placed on the so-called absolute scale using the scaling protocol given in Materials and Methods and elsewhere (26,37,38,40,41). The absolute structure factors for POPC bilayers with 5 mol % TP2, TP2-D, ONEG, and ONEG-D, together with the measured Bragg spacings, are shown in Table 2. In Table 3 we show the center and the 1/e half-width of the Gaussians that describe the deuterium distribution across the bilayers. Whereas the widths of the two deuterium distributions, and , are similar, the centers of the deuterium distributions, and , are different. In particular, the center of the TP2 deuterium distribution is closer to the bilayer center, indicating that TP2 resides deeper in the POPC bilayer, as compared to ONEG.

Table 2.

Absolute structure factors and their experimental uncertainties for POPC multilayers with 5 mol % peptide

| ha | TP2 | TP2-D | ONEG | ONEG-D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −7.90 ± 0.1c | −8.82 ± 0.1 | −2.44 ± 0.02 | −3.78 ± 0.02 |

| 2 | −3.76 ± 0.2 | −6.20 ± 0.2 | −1.28 ± 0.03 | −1.94 ± 0.03 |

| 3 | 4.68 ± 0.3 | 5.70 ± 0.3 | 1.34 ± 0.03 | 1.96 ± 0.04 |

| 4 | −3.80 ± 0.2 | −3.60 ± 0.3 | −0.53 ± 0.03 | −0.64 ± 0.04 |

| d (Å)b | 51.3 ± 0.5 | 51.3 ± 0.5 | 47.4 ± 0.3 | 47.4 ± 0.3 |

Diffraction order.

Bragg spacing. For comparison, the Bragg spacing of neat POPC bilayers at 76% RH is 52.4 ± 0.3 Å.

Uncertainties in the structure factors are standard deviations calculated using the square-root of the number of raw counts collected.

Table 3.

Gaussian parameters for the TP2 and ONEG deuterium distributions in POPC bilayers containing 5 mol % TP2 or ONEG

Center of the deuterium distribution.

Width of the deuterium distribution.

Uncertainties in fit parameters are standard deviations calculated by numerical propagation of the errors in the structure factors.

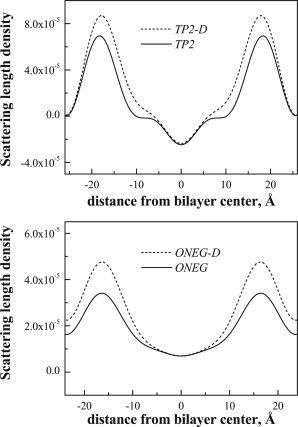

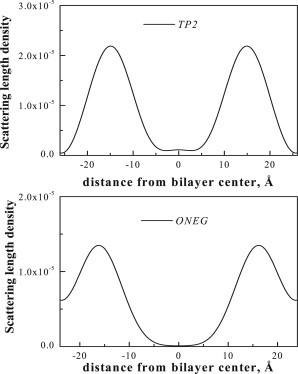

The direct comparison of the absolute profiles in Fig. 4 reveal the position of the deuterated amino acids within the bilayer thickness. The top panel in Fig. 4 compares the profiles of POPC bilayers with 5 mol % TP2 (solid line) and 5 mol % TP2-D (dashed line), hydrated at 76% RH. The difference between the profiles for TP2 and TP2-D is due to the replacement of hydrogens with deuterons in the leucines in TP2 (Fig. 1). The bottom panel compares the profiles for ONEG and ONEG-D. The deuterium label profile for TP2, obtained by subtracting the POPC/TP2 profile from the POPC/TP2-D profile, is shown in Fig. 5 (top) and the difference profile for POPC/ONEG is shown in Fig. 5 (bottom). The difference profiles show that the TP2 deuterium distribution goes to zero at the edge of the unit cell. In the case of ONEG, however, there is significant electron density due to the peptide at the edge of the unit cell, because of the overlap of peptide distributions from the neighboring unit cells. This finding is consistent with the fact that the center of the deuterium Gaussian distribution for TP2 is closer to the bilayer center. As the deuterated amino acids are distributed throughout the peptide sequence, these results suggest that TP2 penetrates deeper into the bilayer, as compared to ONEG. Thus, the incorporation of ONEG into the bilayers is more superficial.

Figure 4.

Absolute neutron scattering length density profiles for bilayers with (top) 5 mol % TP2 (solid line) and TP2-D (dashed line), as well as (bottom) 5 mol % ONEG (solid line) and ONEG-D (dashed line). The profiles are created using the absolute structure factors shown in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Difference neutron scattering profiles, showing the transbilayer distribution of the deuterated amino acids in TP2 (top) and ONEG (bottom).

The Bragg spacing measured in diffraction experiments is very sensitive to peptide-induced changes in bilayer structure. While the Bragg spacing for pure POPC bilayers at 76% RH was 52.4 ± 0.3 Å, the incorporation of ONEG into bilayers decreases the bilayer spacing to 47.4 ± 0.3 Å, indicative of a significant bilayer thinning (Table 2). Bilayer thinning suggests that the area per lipid molecule increases in the presence of ONEG, likely due to increased trans-gauche isomerization of the acyl chains, i.e., due to increased thermal disorder in the bilayer. Despite its deeper penetration into the membrane, 5 mol % TP2 has only a very small effect on the bilayer structure, decreasing the Bragg spacing by 1.1 ± 0.6 Å to 51.3 ± 0.5 Å, a change that is not much larger that the experimental uncertainty in the measurement. Therefore, the TP2 sequence is very well tolerated by the lipids and does not cause large bilayer perturbations even at the high concentration of 5 mol %.

Bilayer destabilization by TP2 and ONEG

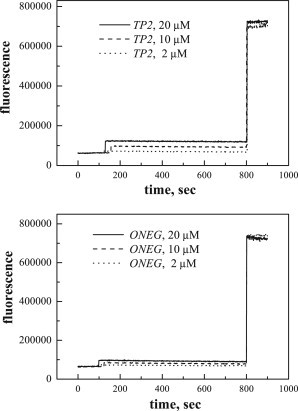

Next, we investigated the effect of TP2 and ONEG on the integrity of POPC bilayers by measuring bilayer permeabilization using the ANTS/DPX vesicle leakage assay. In this assay, the ANTS fluorescence is quenched inside the vesicles due to the presence of DPX, but increases when the encapsulated contents leak out due to ANTS/DPX dilution. The addition of the detergent Triton-X 100, which solubilizes the vesicles, is used to measure the fluorescence for 100% leakage. In Fig. 6, we show that the increase in ANTS fluorescence caused by the addition of TP2 is very small. Although only 5% of TP2 is bound in this experiment, these are the conditions under which translocation takes place (8), and we would expect to see membrane destabilization if it occurs. When the aqueous TP2 concentration is 20 μM, the ratio of bound peptide/lipid is ∼1:1000, a ratio for which many membrane-active peptides cause substantial membrane leakage (24,25,51,52). Similarly to TP2, ONEG causes no leakage from POPC vesicles, but this result is trivial because the bound fraction is only 0.3% under these conditions.

Figure 6.

Leakage of the dye ANTS and the quencher DPX from vesicles in response to TP2 and ONEG. Lipid concentration is 1 mM total. Peptide concentrations are 2, 10, and 20 μM.

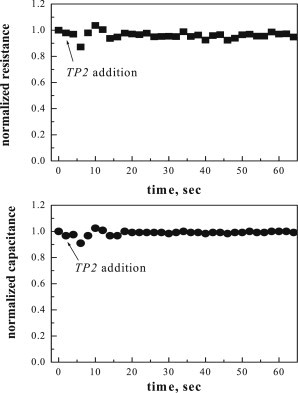

The effect of TP2 on the integrity of surface-supported POPC bilayers was probed using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). EIS yields direct measurements of bilayer resistance and capacitance as a function of time (47). This technique is highly sensitive to subtle defects in bilayer structure that may not be observable in vesicle leakage experiments (45). Supported POPC bilayers on PEG cushions were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The resistance and the capacitance were obtained by fitting the impedance spectra to an ideal parallel RC circuit as described in detail in the literature (45–47,49). The initial membrane resistance (Rm) values were 1.24 × 104 ± 4.6 × 103 Ω cm2. While higher values have been reported (53), this value is very similar to resistances measured for lipid bilayers formed on the tips of patch pipettes (54). The initial capacitance value was 0.74 ± 0.08 μF/cm2, corresponding to a bilayer thickness of 4.8 ± 0.8 nm, assuming a relative permittivity of 4.

Fig. 7 shows the normalized resistance (top) and capacitance (bottom) after the addition of TP2 to a final concentration of 100 μM, corresponding to 1:200 bound peptide/lipid. TP2 does not affect either the resistance or the capacitance of the bilayer at this high concentration. No effects were observed at lower concentrations, either (results not shown).

Figure 7.

Normalized resistance and capacitance of polymer cushioned, surface-supported POPC bilayers after the addition of TP2. The peptide concentration was 100 μM, the lipid concentration was 60 μM, and the bound peptide/lipid was ∼1:200.

We recently published an EIS study of the membrane-permeabilizing peptides melittin and alamethicin using exactly the same methodology and supported bilayers as used in this work (55). The EIS response of the bilayers is extremely sensitive to these pore-forming peptides at bound concentrations that are much lower than the concentration of TP2 used here. For example, alamethicin causes an exponential decrease in the equilibrium bilayer resistance of ∼50%, at the very low bound peptide/lipid of 1:2000. The equilibrium resistance decreases by >90% when this ratio is 1:200 (55). The EIS results in Fig. 7 thus demonstrate that the translocating peptide is causing essentially no disruption of the bilayer at bound concentrations for which alamethicin destroys the bilayer. ONEG binding to bilayers is much lower, such that a direct comparison of the effect of TP2, ONEG, and alamethicin at identical bound concentrations is not feasible.

Discussion

The permeability barrier of the lipid bilayer to polar compounds is due to the hydrophobic nature of the membrane, especially the hydrocarbon core. A small hydrophobic molecule, such as a drug, will likely translocate across a lipid bilayer membrane without disrupting it (56). This occurs by simple stepwise partitioning from water into the bilayer interface, and then from the interface across the hydrocarbon core, which proceeds without any insurmountable energy barriers. A very different mechanism of membrane translocation is used by highly amphipathic molecules such as detergents or pore-forming peptides (57,58). They cross bilayers by disrupting bilayer integrity via various mechanisms, and their translocation is a consequence of bilayer permeabilization.

Both of the peptides studied here were selected in a screen that specifically assayed for lack of bilayer permeabilization. ONEG was selected for lack of permeabilization in a high-throughput Tb3+/dipicolinic acid assay (8) and for lack of translocation at a peptide/lipid of 1:200. TP2 was selected for lack of permeabilization and for rapid translocation. To further validate this functional selection, here we used two different methods to assess the peptide-induced membrane permeabilization at various peptide concentrations, including higher concentrations than the ones used in the high-throughput screen. While the screen was conducted in POPC vesicles containing 10% anionic POPG, the selected peptides were shown to translocate just as efficiently through bilayers made of 100% POPC (8). Therefore, anionic lipids are not required for translocation. In this work, all experiments were conducted with 100% POPC.

First, we used a vesicle-based assay to show that neither peptide causes leakage of the fluorescent probe ANTS or its quencher DPX in experiments conducted at total peptide/lipid up to 1:50 (Fig. 6).

Second, we used impedance spectroscopy, which is much more sensitive to bilayer disruption than the vesicle leakage assays, and we showed that TP2 does not increase the permeability of the surface-supported POPC bilayers at very high concentrations (1 bound peptide per 200 lipids (Fig. 7)).

To further investigate the behavior of the two peptides in bilayers, we assayed membrane binding, peptide secondary structure, peptide disposition in the bilayer, and effects on bilayer structure. We observed modest but obvious differences in the behavior of the two peptides. The translocating peptide TP2, as compared to ONEG:

-

1.

Binds somewhat better as shown by equilibrium dialysis;

-

2.

Is more prone to secondary structure, shown by circular dichroism;

-

3.

Penetrates deeper into bilayers, as evidenced from the position of the Gaussian distribution of the peptides from neutron diffraction; and

-

4.

Is less perturbing to the bilayer structure, as suggested by the smaller decrease in Bragg spacing in diffraction experiments.

Perhaps the most revealing result of these studies is the deeper bilayer insertion of the translocating peptide TP2, in combination with its very small effect on bilayer structure, even at high TP2 bilayer concentrations (5 mol %). At this concentration, TP2 decreased the Bragg spacing by ∼1 Å, while the same amount of the negative peptide ONEG decreased the Bragg spacing of the bilayer by ∼5 Å. Similar bilayer thinning effects have been observed for other membrane-active peptides (24,25,51,52). The thinning effect is attributed to the peptide inserting between lipids at the interface and increasing chain disorder via increased trans-gauche isomerization (24). The small effect of TP2 on bilayer structure suggests that the packing of the lipids is not much affected by peptide insertion, despite the fact that TP2 inserts deeper into the membrane than ONEG.

How can a polycationic peptide like TP2 translocate across bilayers? TP2 would not be predicted to cross bilayers by spontaneous passive diffusion based on octanol partition coefficients, i.e., hydropathy (10) or LogP values (56), because the multiple arginine residues make it much too polar (59). At the same time, it does not cross bilayers using the mechanism of other amphipathic peptides that translocate as a result of bilayer permeabilization. This unusual behavior could be due to the conserved LRLLR motif contained within TP2 and within most of the other translocating peptide sequences that were selected in the screen (8). Very similar highly conserved motifs are also found, concatenated together three times, in the S4 voltage sensor helices of voltage-gated potassium channels (60). In ion channel gating, the S4 segment with its four arginines has been proposed to move freely across the bilayer in response to membrane voltage (61). We have shown experimentally that isolated S4 helices, with four arginine residues, translocate spontaneously across synthetic bilayers (62).

The available evidence in this and previous work suggests that TP2 partitions into and translocates across the membrane as a monomer. For example, the binding experiments reported here for TP2 show no dependence of the partition coefficient on peptide concentrations (Table 1). Previously reported translocation experiments in Marks et al. (8) and recent unpublished data demonstrate that the rate of translocation does not depend on the peptide concentration and on the peptide/lipid, for ratios from 0.00017 (1:6000) to 0.005 (1:200). The lack of concentration dependence of the translocation rate is consistent with the idea that TP2 translocates as a monomer. The isolated S4 helix also translocates at very low peptide/lipid (0.00017), similar to TP2, suggesting that it also translocates as a monomer in synthetic systems, just as it moves across the bilayer as a monomer within the context of the full-length potassium channel.

The LRLLR motif has the same general amino-acid composition as most membrane-destabilizing peptides such as melittin or the antimicrobial peptides, which are rich in cationic and hydrophobic amino acids. Such membrane-destabilizing peptides have “imperfect amphipathicity” (57) in which nonpolar surfaces are interrupted by polar and/or charged residues. When an imperfectly amphipathic, membrane-active peptide partitions into a bilayer, the nonpolar residues are thought to force the insertion of polar residues, thereby disrupting the bilayer structure and allowing the flow of polar solutes across the membrane. As the bilayer is remarkably unperturbed by TP2, the LRLLR motif obviously does not behave like the imperfectly amphipathic antimicrobial peptides even at high concentration. Instead, we speculate that the LRLLR motif is an ideal lipid interaction motif, with the arginine residues in relative positions and separation that allows them to interact with lipid phosphate groups without disrupting the bilayer. When chaperoned by lipid phosphates, the entire complex of peptide and lipid can translocate across the bilayer spontaneously without bilayer disruption. This idea not only explains the selection of the LRLLR motif in the high throughput screen for translocating peptides but also provides a testable hypothesis for the next stage of this work. In particular, it will be interesting to create sequence variants, and then seek correlations among translocation, bilayer disruption, and Bragg spacing from neutron diffraction experiments for these sequence variants.

Acknowledgments

The identification of any commercial product or trade name does not imply endorsement or recommendation by the US National Institute of Standards and Technology.

This study was supported by National Science Foundation grants No. DMR 1003441 and No. DMR 1003411.

References

- 1.Tsong T.Y. Electroporation of cell membranes. Biophys. J. 1991;60:297–306. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82054-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao N.M. Cationic lipid-mediated nucleic acid delivery: beyond being cationic. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2010;163:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowey K., Tanguay J.F., Tabrizian M. Liposome technology for cardiovascular disease treatment and diagnosis. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2012;9:249–265. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2012.647908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerlach S.L., Rathinakumar R., Mondal D. Anticancer and chemosensitizing abilities of cycloviolacin 02 from Viola odorata and psyle cyclotides from Psychotria leptothyrsa. Biopolymers. 2010;94:617–625. doi: 10.1002/bip.21435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayley H., Jayasinghe L. Functional engineered channels and pores (Review) Mol. Membr. Biol. 2004;21:209–220. doi: 10.1080/09687680410001716853. (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heitz F., Morris M.C., Divita G. Twenty years of cell-penetrating peptides: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;157:195–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris M.C., Chaloin L., Divita G. Translocating peptides and proteins and their use for gene delivery. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000;11:461–466. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marks J.R., Placone J., Wimley W.C. Spontaneous membrane-translocating peptides by orthogonal high-throughput screening. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8995–9004. doi: 10.1021/ja2017416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White S.H., Wimley W.C., Hristova K. Protein folding in membranes: determining energetics of peptide-bilayer interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1998;295:62–87. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)95035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wimley W.C., Creamer T.P., White S.H. Solvation energies of amino acid side chains and backbone in a family of host-guest pentapeptides. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5109–5124. doi: 10.1021/bi9600153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wimley W.C., Gawrisch K., White S.H. Direct measurement of salt-bridge solvation energies using a peptide model system: implications for protein stability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:2985–2990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wimley W.C., White S.H. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:842–848. doi: 10.1038/nsb1096-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson W.C., Jr. Secondary structure of proteins through circular dichroism spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1988;17:145–166. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.17.060188.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson W.C., Jr. Protein secondary structure and circular dichroism: a practical guide. Proteins. 1990;7:205–214. doi: 10.1002/prot.340070302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson W.C. Analyzing protein circular dichroism spectra for accurate secondary structures. Proteins. 1999;35:307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasman G.D. Plenum Press; New York: 1996. Circular Dichroism and the Conformational Analysis of Biomolecules. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harroun T.A., Heller W.T., Huang H.W. States of natural melittin by oriented circular dichroism and neutron diffraction. Biophys. J. 1999;76:A124. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olah G.A., Huang H.W. Circular dichroism of oriented α-helices. I. Proof of the exciton theory. J. Chem. Phys. 1988;89:2531–2538. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olah G.A., Huang H.W. Circular dichroism of oriented α-helices. II. Electric field oriented polypeptides. J. Chem. Phys. 1988;89:6956–6962. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu Y., Huang H.W., Olah G.A. Method of oriented circular dichroism. Biophys. J. 1990;57:797–806. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82599-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li E., Hristova K. Imaging Förster resonance energy transfer measurements of transmembrane helix interactions in lipid bilayers on a solid support. Langmuir. 2004;20:9053–9060. doi: 10.1021/la048676l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.You M., Li E., Hristova K. Förster resonance energy transfer in liposomes: measurements of TM helix dimerization in the native bilayer environment. Anal. Biochem. 2005;340:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vogel H. Comparison of the conformation and orientation of alamethicin and melittin in lipid membranes. Biochemistry. 1987;26:4562–4572. doi: 10.1021/bi00388a060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hristova K., Wimley W.C., White S.H. An amphipathic α-helix at a membrane interface: a structural study using a novel x-ray diffraction method. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;290:99–117. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hristova K., Dempsey C.E., White S.H. Structure, location, and lipid perturbations of melittin at the membrane interface. Biophys. J. 2001;80:801–811. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hristova K., White S.H. Determination of the hydrocarbon core structure of fluid dioleoylphosphocholine (DOPC) bilayers by x-ray diffraction using specific bromination of the double-bonds: effect of hydration. Biophys. J. 1998;74:2419–2433. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77950-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Worthington C.R., King G.I. Electron density profiles of nerve myelin. Nature. 1971;234:143–145. doi: 10.1038/234143a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herbette L.G., Chester D.W., Rhodes D.G. Structural analysis of drug molecules in biological membranes. Biophys. J. 1986;49:91–94. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83605-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McIntosh T.J. X-ray diffraction analysis of membrane lipids. In: Brasseur R., editor. Molecular Description of Biological Membrane by Computer-Aided Conformational Analysis. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1990. pp. 241–266. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagle J.F., Zhang R., Suter R.M. X-ray structure determination of fully hydrated Lα phase dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine bilayers. Biophys. J. 1996;70:1419–1431. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79701-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang R., Suter R.M., Nagle J.F. Theory of the structure factor of lipid bilayers. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics. 1994;50:5047–5060. doi: 10.1103/physreve.50.5047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krepkiy D., Mihailescu M., Swartz K.J. Structure and hydration of membranes embedded with voltage-sensing domains. Nature. 2009;462:473–479. doi: 10.1038/nature08542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He K., Ludtke S.J., Huang H.W. Neutron scattering in the plane of membranes: structure of alamethicin pores. Biophys. J. 1996;70:2659–2666. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79835-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsaras J., Yang D.S.C., Epand R.M. Fatty-acid chain tilt angles and directions in dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine bilayers. Biophys. J. 1992;63:1170–1175. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81680-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dura J.A., Pierce D.J., White S.H. AND/R: advanced neutron diffractometer/reflectometer for investigation of thin films and multilayers for the life sciences. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2006;77:74301. doi: 10.1063/1.2219744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han X., Mihailescu M., Hristova K. Neutron diffraction studies of fluid bilayers with transmembrane proteins: structural consequences of the achondroplasia mutation. Biophys. J. 2006;91:3736–3747. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.092247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han X., Hristova K., Wimley W.C. Protein folding in membranes: insights from neutron diffraction studies of a membrane β-sheet oligomer. Biophys. J. 2008;94:492–505. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han X., Hristova K. Viewing the bilayer hydrocarbon core using neutron diffraction. J. Membr. Biol. 2009;227:123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00232-008-9151-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs R.E., White S.H. The nature of the hydrophobic binding of small peptides at the bilayer interface: implications for the insertion of transbilayer helices. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3421–3437. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiener M.C., White S.H. Transbilayer distribution of bromine in fluid bilayers containing a specifically brominated analogue of dioleoylphosphatidylcholine. Biochemistry. 1991;30:6997–7008. doi: 10.1021/bi00242a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiener M.C., King G.I., White S.H. Structure of a fluid dioleoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer determined by joint refinement of x-ray and neutron diffraction data. I. Scaling of neutron data and the distributions of double bonds and water. Biophys. J. 1991;60:568–576. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82086-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellens H., Bentz J., Szoka F.C. pH-induced destabilization of phosphatidylethanolamine-containing liposomes: role of bilayer contact. Biochemistry. 1984;23:1532–1538. doi: 10.1021/bi00302a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hristova K., Selsted M.E., White S.H. Interactions of monomeric rabbit neutrophil defensins with bilayers: comparison with dimeric human defensin HNP-2. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11888–11894. doi: 10.1021/bi961100d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hristova K., Selsted M.E., White S.H. Critical role of lipid composition in membrane permeabilization by rabbit neutrophil defensins. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24224–24233. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin J., Motylinski J., Hristova K. Interactions of membrane active peptides with planar supported bilayers: an impedance spectroscopy study. Langmuir. 2012;28:6088–6096. doi: 10.1021/la300274n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin J., Szymanski J., Hristova K. Electrically addressable, biologically relevant surface-supported bilayers. Langmuir. 2010;26:12054–12059. doi: 10.1021/la101084b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin J., Merzlyakov M., Searson P.C. Impedance spectroscopy of bilayer membranes on single crystal silicon. Biointerphases. 2008;3:FA33–FA40. doi: 10.1116/1.2896117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang W.K., Wimley W.C., Merzlyakov M. Characterization of antimicrobial peptide activity by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:2430–2436. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin J., Szymanski J., Hristova K. Effect of a polymer cushion on the electrical properties and stability of surface-supported lipid bilayers. Langmuir. 2010;26:3544–3548. doi: 10.1021/la903232b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wimley W.C., Hristova K., White S.H. Folding of β-sheet membrane proteins: a hydrophobic hexapeptide model. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;277:1091–1110. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heller W.T., Waring A.J., Huang H.W. Membrane thinning effect of the β-sheet antimicrobial protegrin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:139–145. doi: 10.1021/bi991892m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ludtke S., He K., Huang H. Membrane thinning caused by magainin 2. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16764–16769. doi: 10.1021/bi00051a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Montal M., Mueller P. Formation of bimolecular membranes from lipid monolayers and a study of their electrical properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1972;69:3561–3566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coronado R., Latorre R. Phospholipid bilayers made from monolayers on patch-clamp pipettes. Biophys. J. 1983;43:231–236. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(83)84343-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiedman G., Herman K., Hristova K. The electrical response of bilayers to the bee venom toxin melittin: evidence for transient bilayer permeabilization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828:1357–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhal S.K., Kassam K., Pearl G.M. The Rule of Five revisited: applying log D in place of log P in drug-likeness filters. Mol. Pharm. 2007;4:556–560. doi: 10.1021/mp0700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wimley W.C. Describing the mechanism of antimicrobial peptide action with the interfacial activity model. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:905–917. doi: 10.1021/cb1001558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wimley W.C., Hristova K. Antimicrobial peptides: successes, challenges and unanswered questions. J. Membr. Biol. 2011;239:27–34. doi: 10.1007/s00232-011-9343-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hristova K., Wimley W.C. A look at arginine in membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 2011;239:49–56. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9323-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang Y.X., Lee A., MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature. 2003;423:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nature01580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang Y.X., Ruta V., MacKinnon R. The principle of gating charge movement in a voltage-dependent K+ channel. Nature. 2003;423:42–48. doi: 10.1038/nature01581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.He J., Hristova K., Wimley W.C. A highly charged voltage-sensor helix spontaneously translocates across membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:7150–7153. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]