Abstract

To investigate the possibility of a Hispanic mortality advantage, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the published longitudinal literature reporting Hispanic individuals’ mortality from any cause compared with any other race/ethnicity. We searched MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, HealthSTAR, and PsycINFO for published literature from January 1990 to July 2010.

Across 58 studies (4 615 747 participants), Hispanic populations had a 17.5% lower risk of mortality compared with other racial groups (odds ratio = 0.825; P < .001; 95% confidence interval = 0.75, 0.91). The difference in mortality risk was greater among older populations and varied by preexisting health conditions, with effects apparent for initially healthy samples and those with cardiovascular diseases. The results also differed by racial group: Hispanics had lower overall risk of mortality than did non-Hispanic Whites and non-Hispanic Blacks, but overall higher risk of mortality than did Asian Americans.

These findings provided strong evidence of a Hispanic mortality advantage, with implications for conceptualizing and addressing racial/ethnic health disparities.

DESPITE A SIGNIFICANTLY more disadvantaged risk factor profile, Hispanics in the United States often experience similar or better health outcomes across a range of health and disease contexts compared with non-Hispanic Whites (NHWs), an epidemiological phenomenon commonly referred to as the “Hispanic paradox.” Among the most salient features of this advantage is evidence that Hispanics appear to live longer than NHWs.1–3 These findings are largely based on national cohort data, with mortality data from the US Vital Statistics System used in the numerator and population counts from the US Census used in the denominator, yielding a death rate statistic. The classic explanations for these paradoxical findings suggest that either the denominator is artificially low because of Hispanics returning to their countries of origin before death (the “salmon bias hypotheses”) or that the numerator is not representative due to the healthiest Hispanics migrating to the United States (the “healthy migrant hypothesis”). These hypotheses have been largely refuted.4 The contemporary overarching concern is that the statistical estimation approach remains flawed because of underreporting of ethnicity on death certificates. Despite recent data suggesting that the associated error is negligible,5,6 the validity of the paradox remains in question due to its strong ties to this methodology.

One solution to these issues is to examine longitudinal studies in which race and ethnicity are assessed at study entry and participants are followed longitudinally to mortality. This literature has added a wealth of data for and against a Hispanic mortality advantage, but has failed to clarify the overall relationship. A number of factors impede consensus, including differences in sample size, selection criteria, methodologies, follow-up time, statistical reporting, and outcomes (i.e., morbidity, specific-cause mortality, all-cause mortality). In addition, at least 5 narrative literature reviews of the associated data7–11 were published in the last decade, asserting the level of interest but failing to provide an empirical test (e.g., meta-analysis) to clarify the discrepancy. Hence, the current status of the Hispanic mortality paradox can best be described as one of great interest with significant logistical confusion.

We systematically reviewed the longitudinal literature, comparing Hispanic mortality rates with those of other racial/ethnic groups and conducted a meta-analysis of the available data as a definitive test of whether there is a relative Hispanic mortality advantage. Resolving the validity of the phenomenon would facilitate future research efforts to identify contributing resilience factors that might lead to targeted interventions. In the present study, we focused on all-cause mortality (death from any cause) as the primary dependent variable and evaluated mortality within specific disease contexts to the extent that sufficient data were available. We improved on previous reviews by using meta-analytic procedures that took into account the differences in available studies regarding sample size, participant characteristics, selection criteria, and outcomes.

METHODS

Studies were identified through 2 techniques. First, we conducted extensive electronic database searches from January 1990 to July 2010, using MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, HealthSTAR, and PsycINFO. January 1990 was used as the beginning search date because of methodological changes in the use of the terms such as Hispanic in race and ethnicity data collection and publication efforts.12,13 To capture the broadest possible sample of relevant articles, 3 search term categories were used: (1) Hispanic (Hispanic, Latino, Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban), (2) mortality (mortality, death, longevity, survival, life span), and (3) design (prospective, longitudinal). Second, we manually examined the reference sections of past reviews and of studies meeting the inclusion criteria to locate articles not identified in the database searches.

Inclusion Criteria

We included only published studies meeting the following criteria in the meta-analysis: (1) written in English or Spanish, (2) used a longitudinal design, and (3) provided quantitative data regarding Hispanic mortality at the individual level compared with that of other racial/ethnic groups.

We excluded studies in which the outcome was not explicitly stated as mortality (e.g., combined outcomes of morbidity and mortality), studies of infant mortality, single-case designs, and reports with exclusively aggregated data (e.g., census-level statistics). We included all other types of quantitative research designs that were longitudinal and yielded a statistical estimate of the risk of mortality among Hispanic populations compared with that of other racial/ethnic groups. There were no age limitations other than those related to studies of infant mortality. However, the published literature on mortality was largely skewed toward older ages, as reflected here.

Data Abstraction

Articles were independently coded by 2 teams with 2 members each. A third independent member then compared the 2 ratings, resolving discrepancies through joint review with the teams. Coders extracted several objectively verifiable characteristics of the studies: (1) the number of participants and their composition by age, ethnicity, gender, and preexisting health conditions (if any), as well as the cause of mortality; (2) length of follow-up; and (3) research design. Given the substantial heterogeneity among Hispanic peoples exemplified by differences in culture, traditions, and importantly, health outcomes, we further sought to code by country of origin or nativity when such data were available.

Data within studies were often reported in terms of odds ratios (ORs), the likelihood of mortality contrasted by ethnic group. Because OR values cannot be meaningfully aggregated, all effect sizes reported within studies were transformed to the natural log ORs for analyses and then transformed back to ORs for interpretation. When effect size data were reported in any metric other than ORs or the natural log ORs, we transformed those values using statistical software programs and macros (Comprehensive Meta-Analysis14). In many cases, we calculated effect sizes from frequency data in matrixes of mortality status by ethnicity. In cases when frequency data were not reported, we recovered the cell probabilities from the reported risk ratio and marginal probabilities. Across studies, we assigned OR values less than 1.00 to data indicative of decreased mortality among Hispanics and OR values greater than 1.00 to data indicative of increased mortality among Hispanics relative to the comparison group(s).

When multiple effect sizes were reported within a study at the same time, we averaged the values (weighted by SE) to avoid violating the assumption of independent samples. When a study contained multiple effect sizes across time, we extracted the data from the longest follow-up period. If a study used statistical controls in calculating an effect size, we extracted the data from the model utilizing the fewest statistical controls. We coded the research design used rather than the estimate risk of individual study bias. The coding protocol is available from the authors.

Information obtained from the studies was extracted directly from the reports. As a result, the interrater agreement was high for categorical variables (mean Cohen’s κ = 0.97; SD = 0.02) and for continuous variables (mean intraclass correlation = 0.93; SD = 0.14). Discrepancies across coders were resolved through further scrutiny of the article until consensus was obtained.

Aggregate effect sizes were calculated using random effects models following confirmation of heterogeneity. A random effects approach yields results that generalize beyond the sample of studies actually reviewed.15 We assumed that the results would differ as a function of participant characteristics (i.e., age, gender) and study design (i.e., length of follow-up). Random effects models take this between-studies variation into account, whereas fixed effects models do not.16

RESULTS

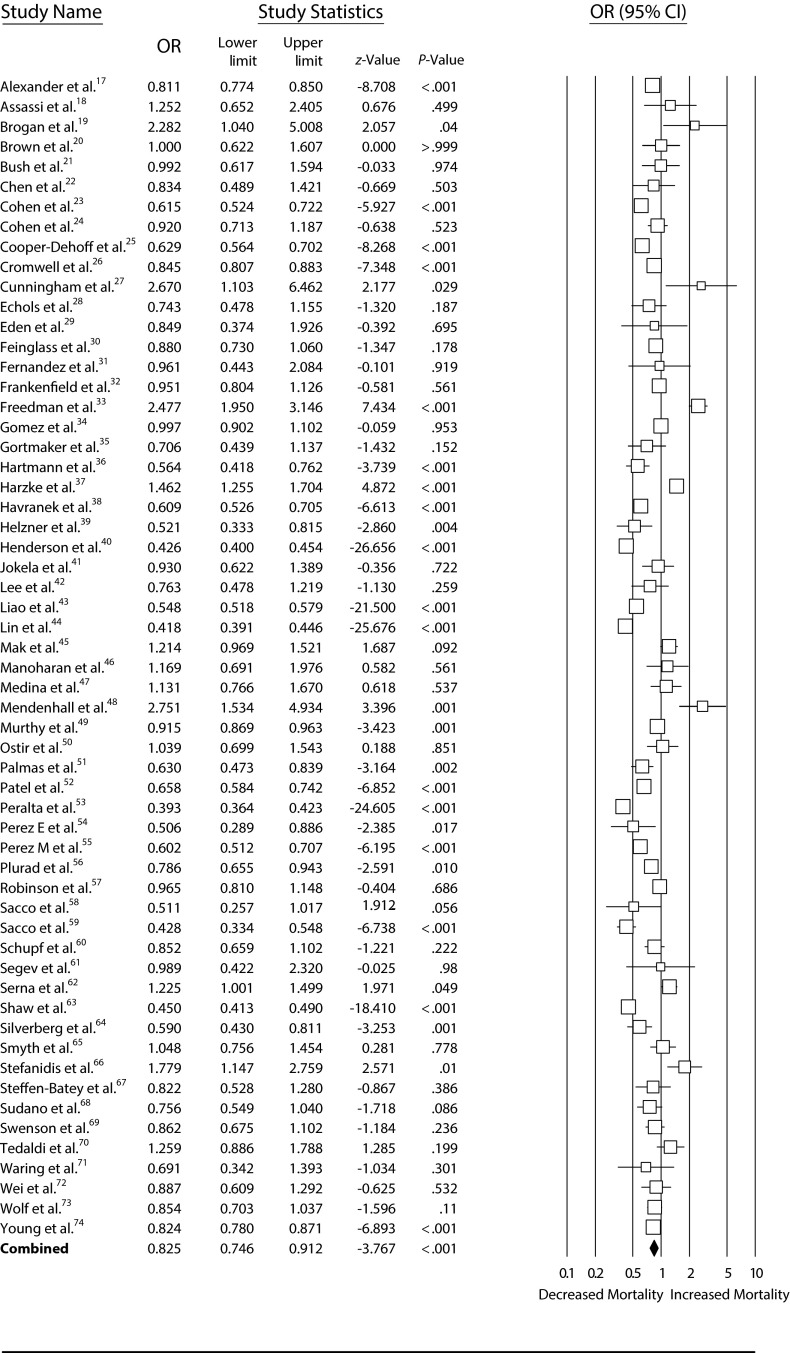

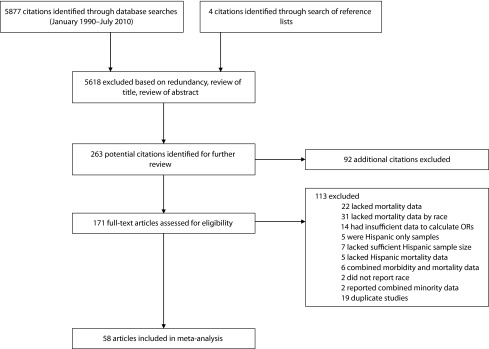

Figure 1 shows the study selection process. Statistically nonredundant effect sizes were extracted from 58 studies (Table 1).17–74 Data were reported from 4 615 747 total participants, with an average composition of 26% Hispanic participants within studies. The mean ages of participants at initial evaluation were 54.6 years (SD = 11.6) for Hispanics and 56.1 years (SD = 11.7) for comparison groups. Hispanic participants consisted of 44% women, and comparison groups included 45% women.

FIGURE 1—

Selection of articles for meta-analysis: 1990 to 2010.

Note. OR = odds ratio.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of Included Studies: 1990–2010

| Source | Total, No. | Hispanic, No. (%) | Female, % | Mean Age, Years | Follow-Up, Years | Health Status at Study Entry | Analysis Category |

| Alexander et al.17 | 90 316 | 9835 (11) | 55 | 69 | 1 | CVD | CVD |

| Assassi et al.18 | 250 | 71 (28) | 87 | 47 | 6 | Scleroderma | Other |

| Brogan et al.19 | 1027 | 31 (3) | 35 | 35 | < 1 | Respiratory failure | Other |

| Brown et al.20 | 327 | 125 (38) | 38 | 37 | 5 | HIV/AIDS | HIV/AIDS |

| Bush et al.21 | 2486 | 92 (4) | 40 | 65 | 5 | CVD | CVD |

| Chen et al.22 | 281 | 100 (36) | 19 | 59 | 3 | Cancer | Cancer |

| Cohen et al.23 | 15 610 | 2600 (17) | 17 | 36 | 3 | HIV/AIDS | HIV/AIDS |

| Cohen et al.24 | 27 788 | 734 (3) | 26 | 59 | < 1 | CVD | CVD |

| Cooper-Dehoff et al.25 | 22 576 | 8045 (36) | 61 | 66 | 3 | CVD | CVD |

| Cromwell et al.26 | 692 574 | 9868 (1) | NA | > 65 | 1 | CVD | CVD |

| Cunningham et al.27 | 200 | 36 (18) | 5 | 38 | 6 | HIV/AIDS | HIV/AIDS |

| Echols et al.28 | 7007 | 344 (5) | 38 | 63 | 1 | CVD | CVD |

| Eden et al.29 | 107 | 64 (60) | 73 | 62 | 7 | Stroke | Other |

| Feinglass et al.30 | 25 568 | 3628 (14) | 44 | 72 | 5 | Extremity bypass | Other |

| Fernandez et al.31 | 396 | 220 (56) | 86 | 35 | 10 | Autoimmune | Other |

| Frankenfield et al.32 | 7723 | 994 (13) | 46 | 59 | 1 | Kidney disease | Other |

| Freedman et al.33 | 15 329 | 970 (6) | 55 | 44 | 12 | Cancer | Cancer |

| Gomez et al.34 | 41 901 | 2061 (5) | 50 | > 65 | 7 | Cancer | Cancer |

| Gortmaker et al.35 | 1028 | 358 (35) | 50 | 7 | 4 | HIV/AIDS | HIV/AIDS |

| Hartmann et al.36 | 980 | 483 (41) | 50 | 66 | 5 | Stroke | Other |

| Harzke et al.37 | 1 238 317 | 311 082 (25) | 0 | 28 | 5 | None apparent | None/community |

| Havranek et al.38 | 7495 | 1789 (24) | 49 | 56 | < 1 | CVD | CVD |

| Helzner et al.39 | 323 | 179 (55) | 70 | 87 | 4 | Dementia | Other |

| Henderson et al.40 | 71 798 | 41 665 (58) | 52 | 63 | 6 | None apparent | None/community |

| Jokela et al.41 | 8544 | 1736 (20) | 50 | 20 | 25 | None apparent | None/community |

| Lee et al.42 | 446 | 312 (70) | 61 | > 60 | 8 | None apparent | None/community |

| Liao et al.43 | 696 697 | 52 725 (8) | 53 | 38 | 9 | None apparent | None/community |

| Lin et al.44 | 553 307 | 33 954 (6) | 54 | > 25 | 11 | None apparent | None/community |

| Mak et al.45 | 15 376 | 1613 (10) | 34 | 64 | 3 | CVD | CVD |

| Manoharan et al.46 | 400 | 67 (17) | 33 | 67 | 14 | Cancer | Cancer |

| Medina et al.47 | 584 | 236 (40) | 60 | 62 | 4 | Diabetes | Other |

| Mendenhall et al.48 | 428 | 63 (15) | 0 | 49 | 5 | Liver Disease | Other |

| Murthy et al.49 | 100 618 | 10 393 (10) | 47 | 59 | 2 | Kidney disease | Other |

| Ostir et al.50 | 506 | 153 (30) | 51 | 81 | 5 | None apparent | None/community |

| Palmas et al.51 | 1178 | 451 (38) | 55 | 72 | 7 | Diabetes | Other |

| Patel et al.52 | 66 397 | 1114 (2) | 56 | 73 | 8 | None apparent | None/community |

| Peralta et al.53 | 39 550 | 12 076 (31) | 59 | 62 | 4 | Kidney disease | Other |

| Perez E et al.54 | 312 | 91 (29) | 46 | 58 | 20 | Cancer | Cancer |

| Perez M et al.55 | 44 171 | 2625 (6) | 9 | 54 | 8 | CVD | CVD |

| Plurad et al.56 | 3998 | 2495 (62) | 18 | 33 | 7 | Sepsis | Other |

| Robinson et al.57 | 6677 | 673 (10) | 45 | 57 | 5 | Kidney disease | Other |

| Sacco et al.58 | 394 | 82 (21) | 51 | 63 | 1 | Stroke | Other |

| Sacco et al.59 | 2670 | 1443 (54) | 63 | 66 | 9 | None apparent | None/community |

| Schupf et al.60 | 2247 | 876 (39) | 66 | 76 | 3 | None apparent | None/community |

| Segev et al.61 | 79 034 | 9846 (12) | 59 | 39 | 6 | None apparent | None/community |

| Serna et al.62 | 5122 | 413 (8) | 41 | NA | 5 | Cancer | Cancer |

| Shaw et al.63 | 346 075 | 7823 (2) | 47 | 61 | < 1 | CVD | CVD |

| Silverberg et al.64 | 4787 | 661 (14) | 10 | 37 | 9 | HIV/AIDS | HIV/AIDS |

| Smyth et al.65 | 581 | 323 (56) | 0 | 25 | 33 | Heroin addiction | Other |

| Stefanidis et al.66 | 408 | 296 (73) | 44 | 54 | 16 | Cancer | Cancer |

| Steffen-Batey et al.67 | 406 | 196 (48) | 41 | 59 | 7 | CVD | CVD |

| Sudano et al.68 | 8400 | 723 (9) | 52 | 56 | 6 | None apparent | None/community |

| Swenson et al.69 | 1862 | 921 (49) | 57 | 52 | 11 | Diabetes | Other |

| Tedaldi et al.70 | 1301 | 225 (17) | 20 | 38 | 5 | HIV/AIDS | HIV/AIDS |

| Waring et al.71 | 956 | 37 (4) | 73 | 72 | 13 | Dementia | Other |

| Wei et al.72 | 3735 | 2630 (70) | 59 | 43 | 8 | None apparent | None/community |

| Wolf et al.73 | 9303 | 979 (11) | 44 | 61 | 1 | Kidney disease | Other |

| Young et al.74 | 337 870 | 26 544 (8) | 1 | 64 | 2 | Diabetes | Other |

Note. CVD = cardiovascular disease; NA = not available.

Research reports typically failed to describe the specific ethnic heritage of the Hispanic participants (80% omitted this information), but 8 studies (15%) were specific to Mexican Americans,20,29,33,42,47,52,67,72 1 study was specific to Puerto Rican Americans,48 and 5 studies (9%) involved participants from a variety of ethnic backgrounds.24,25,31,36,51 Several studies (22%) involved initially healthy participants, but 24% of studies involved patients with cardiovascular disease (CVD), 12% with cancer, 10% with HIV infection, 7% with diabetes, 5% with renal disease, and the remaining 20% with a variety of conditions, including liver disease and dementia. Research reports most often (91%) considered all-cause mortality, but some restricted evaluations to mortality associated with CVD (5%) or other specific causes (4%). Only 8 studies (14%) involved a medical intervention21,24,25,33,35,45,62,73; most merely tracked participants’ mortality over time. Participants were followed for an average of 6.9 years (SD = 5.9; range = 1 month to 33 years). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines were adhered to in the design and reporting of this study.75,76

Omnibus Analysis

Across the 58 studies, the random effects weighted average effect size was OR = 0.825 (P < .001; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.75, 0.91). Consistent with the hypothesis, Hispanic ethnicity was associated with a 17.5% mortality advantage.

As shown in Figure 2, ORs ranged from 0.39 to 2.75, with a very large degree of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 96%; Q(57) = 1564; P < .001; τ2 = 0.12), suggesting that systematic effect size variability was unaccounted for. Thus, it was likely that factors associated with the studies themselves (e.g., publication status), participant characteristics (e.g., age, health status), and, or the research design (e.g., length of follow-up) might have moderated the overall results. We therefore conducted additional analyses to determine the extent to which the variability in the effect sizes was moderated by these variables.

FIGURE 2—

Meta-analysis of Hispanic ethnicity and all-cause mortality: 1990–2010.

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Evaluation for Publication Bias

To assess the possibility of publication bias,77 we conducted 4 analyses. First, we calculated Orwin’s fail-safe N,78 the theoretical number of unpublished studies with effect sizes averaging zero (no effect) that would need to be located to reduce the overall magnitude of the results obtained to a trivial estimate of 1.0 > OR > 0.95. Based on this calculation, at least 367 additional studies averaging OR = 1.0 would need to be found to render the results of the present meta-analysis as negligible. Second, we utilized both Egger’s regression test79 and the alternative to that test recommended by Peters et al.,80 which is better suited to data in OR format. The results of these 2 analyses failed to reach statistical significance (P > .05). Third, we generated a “funnel plot”81 of the studies’ log ORs by the SEs. The data obtained from this meta-analysis were not symmetrically distributed around the grand mean; there appeared to be multiple studies “missing” from the bottom left corner of the distribution. However, these studies were in the opposite corner from what would have been expected. Typically, “missing” studies were in the region of nonsignificance if publication bias was present. In this case, the data underrepresented studies with relatively fewer participants that demonstrated lower mortality rates among Hispanics. Finally, we employed the “trim and fill” methodology described by Duval and Tweedie.82,83 This analysis indicated that when 14 estimated “missing” studies were included in the analysis, the overall effect size was calculated to be OR = 0.70 (95% CI = 0.64, 0.77), indicating that Hispanic participants were 30% less likely to die than were comparison group members over the same time period.

Based on these 4 analyses, we concluded that the data did not reflect publication bias per se, but that they might represent a conservative estimate of risk for mortality among Hispanic populations.

Moderation by Participant and Study Characteristics

To investigate whether the lower risk of mortality among Hispanic populations varied as a function of participant characteristics within studies, we conducted analyses involving participants’ age, gender, and preexisting diagnoses. We also investigated any differences across studies that may be due to length of follow-up, type of research design, and cause of mortality.

To establish whether the average age of the sample accounted for significant between-studies variance, the effect sizes from the 53 studies that reported participants’ average age at intake were correlated with the corresponding effect size for that study. The resulting random effects weighted correlation was −0.28 (P = .03), indicating that studies with older populations tended to demonstrate lower risk of mortality among Hispanic participants relative to comparison groups. As a first step to verify that this association was specific to chronological age, we investigated the possible confounding association with trends over time. However, when we correlated the effect sizes with the year of initial data collection and with a variable created by subtracting the average age of participants at the start of the study from the year of initial data collection (an estimate of the average year of participant birth), the resulting values of r = −0.08 and r = 0.22 did not approach statistical significance (P > .1). Thus, the findings within studies did not consistently change over time. Because older populations were more likely to receive treatment than were younger populations, we conducted a second analysis to verify the association observed with participant age by simultaneously regressing participant age and the type of research study (intervention vs observation) on study effect size. In this model, the average age of participants remained statistically significant (b = −0.28, P = .04), but the type of research study (intervention vs observation) did not. The differences observed in risk for mortality appeared to be moderated by participant age.

Similar random effects weighted correlations with the gender composition of each sample (using percentage who were female; r = −0.23) and the length of time participants were followed (r = 0.07) did not reach statistical significance (P > .05). Furthermore, no differences in the average effect sizes were found between studies using prospective versus retrospective designs (Q1,57 = 0.1; P > .05). Studies evaluating all-cause mortality had effect sizes of equivalent magnitude to those from the studies in which a specific cause of death was evaluated (i.e., cancer; Q = 0.3; P > .05). Thus, the omnibus results presented earlier were not moderated by these variables.

As shown in Table 2, statistically significant differences were found across participants’ type of health condition at the point of initial evaluation (Q = 11.5; P = .02). Community samples of Hispanics with no identified health impairment had the greatest mortality advantage (estimated 30%) relative to non-Hispanics. Hispanic ethnicity was also associated with a 25% reduced mortality advantage among individuals with CVD and an estimated 16% advantage among persons with a variety of other preexisting health conditions. However, Hispanics diagnosed with HIV/AIDS or cancer had a risk of mortality that did not significantly differ from non-Hispanics.

TABLE 2—

Analyses of Weighted Average Effect Sizes Across Type of Preexisting Health Condition: 1990–2010

| Type of Health Conditiona | Studies, No. | OR (95% CI) |

| None apparent (community samples) | 13 | 0.70 (0.58, 0.85) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 11 | 0.75 (0.61, 0.91) |

| Cancer | 7 | 1.21 (0.92, 1.59) |

| HIV/AIDS | 6 | 0.86 (0.64, 1.17) |

| Other conditions | 21 | 0.84 (0.72, 0.99) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio, transformed from random effects weighted natural log OR; Qb = Q-value for variance between groups.

Qb = 115; P = .02.

Because studies compared Hispanic participants with different ethnic groups, we conducted a random effects weighted analysis of variance across the several comparisons conducted within studies (such that each study contributed as many effect sizes as it had unique comparisons with different ethnic groups84). As shown in Table 3, there was a significant difference across ethnicity (Q = 6.5; P < .05). Hispanic participants were less likely to die over time compared with both NHWs and non-Hispanic Blacks (NHBs), but they were more likely to die than were Asian Americans during the same follow-up period.

TABLE 3—

Odds of Survival by Race Compared With Hispanics: 1990–2010

| Racea | Studies, No. | OR (95% CI) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 40 | 0.87 (0.76, 0.99) |

| Asian | 9 | 1.19 (0.90, 1.56) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 53 | 0.81 (0.73, 0.91) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio, transformed from random effects weighted natural log OR; Qb = Q-value for variance between groups.

Qb = 6.5; P = .04.

DISCUSSION

Results of this meta-analysis showed that Hispanic ethnicity was associated with a 17.5% lower mortality rate relative to non-Hispanics, a rate that was highly comparable to the 20% advantage reported by Arias et al.5 using the alternative death statistic estimation strategy. The omnibus finding in the present study was moderated by age, such that the effect became stronger among older participants, a finding similar to that which was recently reported using the estimation approach.85 However, the date of data collection did not moderate the effect, suggesting that the trajectory of this mortality effect did not change (i.e., weaken) over time. The Hispanic mortality advantage varied as a function of preexisting health status at study entry. Specifically, Hispanics displayed a significant mortality advantage among studies of initially healthy samples and in the context of CVD and other health conditions, such as renal disease. With respect to studies of persons with cancer and HIV/AIDS, Hispanics and non-Hispanics experienced equivalent mortality risk. Findings also indicated that although Hispanics had a significant overall mortality advantage relative to NHWs and NHBs, they were marginally disadvantaged relative to Asian Americans.

When considered along with the consistent state and national vital statistics evidence, including the recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report clearly stating a Hispanic ethnicity mortality advantage,3 it might be time to move beyond the question of the existence of the Hispanic mortality paradox and onto investigations into the causes of such resilience. An important conceptual consideration was that the observed mortality advantage, as well as the broader health outcome advantages evident in the Hispanic paradox, may reflect resilience at several points in the course of disease. Hispanics might be less susceptible than some other races to illness in general or to specific conditions with high mortality rates, such as CVD. It was also possible that the rate of disease progression might be slower among Hispanics, resulting in lower morbidity and greater longevity. Finally, the mortality advantage might reflect an advantage in survival and recovery from acute clinical events (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke). Hence, further research is needed to ascertain whether the observed Hispanic mortality advantage reflects advantages at specific points in the disease course and whether such time-point differences vary by disease context.

Several risk and resilience factors might contribute to these effects, including potential biological (e.g., genetics, immune functioning), behavioral (e.g., diet, smoking), psychological (e.g., stress, personality), and social (e.g., acculturation, social cohesion) differences.86 Although not assessed in the present study, lower socioeconomic status (SES) is a robust predictor of worse health outcomes.87 However, the present findings challenged the generalizability of this relationship given the typically lower SES of Hispanics relative to NHWs. It is possible that SES either does not contribute to risk among Hispanics or confers risk only as moderated by some third variable. For example, emerging data suggested that acculturation moderates the relationship between SES and disease risk among Hispanics, such that there is a buffering effect of SES associated with low levels of acculturation and a more traditional SES gradient effect at higher acculturation levels.88 Acculturation might be a proxy for social behaviors and cultural values that buffer against the stress of economic and environmental disadvantages. It was also possible that the relative impact of traditional risk factors, such as diabetes and lipids, differ by ethnicity and contribute to the observed paradox. More research is needed to identify risk and resilience mechanisms as well as to understand potentially complex interaction patterns that may explain the observed effects.

The present study is a reminder to physicians and researchers about the heterogeneity in racial/ethnic minority health. Despite similar risk factor profiles, Hispanics had significantly lower all-cause mortality relative to NHBs. Such findings support a need for Hispanic-specific comparative research to determine where such differences occur in specific disease courses and outcomes and to investigate potential racial and ethnic differences in the relative weight or influence of identified risk factors for disease. Given evidence of Hispanic heterogeneity in health outcomes, subgroup comparative research is also warranted.

Limitations

We could not entirely rule out the possibility of selection bias as an alternative explanation for the findings. Although we made significant efforts to identify all relevant published studies, and data checks indicated no significant violations of publication distribution, our results might yet reflect some degree of bias. For example, limiting inclusion to only those studies in English or Spanish might have resulted in a language bias. The number of available studies also limited our ability to examine mortality in specific contexts, including diabetes, autoimmune conditions, injury, neurologic disorders, and others, as well as test effects of acculturation or generational status. We were also unable to address questions regarding whether the observed effect was constant or decreased over time. Study availability might also have limited our ability to detect subtle effects, as in the context of cancer and HIV, where observed effects might have been significant with a larger number of studies. Lack of reporting also limited our ability to examine several key moderators, including SES and health behaviors, which were shown to influence outcomes.89 To these points, we would note that we did not examine unpublished manuscripts that could also affect findings. Finally, the analyzed sample was predominantly Mexican American, which likely limited generalizability across Hispanic subgroups, particularly given evidence of significant heterogeneity in Hispanic subgroup mortality outcomes.90,91

Conclusions

These findings should serve as a cornerstone to document a comparative Hispanic mortality advantage in the context of a disadvantaged risk factor profile and to demonstrate important heterogeneity in racial/ethnic minority health. Furthermore, these findings highlighted the need for specific comparative studies involving Hispanics as opposed to generalizing findings of Black-White differences. A next challenge is to identify factors that promote resilience across the life span, and in turn, have the potential for informing interventions for all.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Departments of Psychology at the University of North Texas and Brigham Young University.

We would like to thank Erin Kauffman, Courtney C. Prather, Lauren Smith (University of North Texas) and Jameson VanDyke and Randy Gilliland (Brigham Young University) for their assistance in the literature search and coding. We would also like to thank Linda Gallo (San Diego State University), Karen Matthews (University of Pittsburgh), and Bert Uchino (University of Utah) for their useful comments on this article.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because data were obtained from secondary sources. After consultation with our respective institutional review boards, approval was not sought given the nature of the study and its use of published, de-identified data.

References

- 1.Markides KS, Coreil J. The health of Hispanics in the southwestern United States: an epidemiologic paradox. Public Health Rep. 1986;101(3):253–265 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, Rogot E. Mortality by Hispanic status in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(20):2464–2468 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arias E. United States Life Tables by Hispanic Origin. Vol 152 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abraído-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1543–1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias E, Eschbach K, Schauman WS, Backlund EL, Sorlie PD. The Hispanic mortality advantage and ethnic misclassification on US death certificates. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(Suppl 1):S171–S177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith DP, Bradshaw BS. Rethinking the Hispanic paradox: death rates and life expectancy for US non-Hispanic White and Hispanic populations. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1686–1692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(3):496–518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Markides KS, Eschbach K. Aging, migration, and mortality: current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(Spec No 2):S68–S75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lerman-Garber I, Villa AR, Caballero E. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Is there a true Hispanic paradox? Rev Invest Clin. 2004;56(3):282–296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morales LS, Lara M, Kington RS, Valdez RO, Escarce JJ. Socioeconomic, cultural, and behavioral factors affecting Hispanic health outcomes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2002;13(4):477–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palloni A, Morenoff JD. Interpreting the paradoxical in the Hispanic paradox: demographic and epidemiologic approaches. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;954:140–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greico EM, Cassidy R. C. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson C, Jung K. Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States Regions, Divisions, and States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Rothstein H. Comprehensive Meta-analysis. Version 2 Englewood, NJ: Biostat; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychol Methods. 1998;3(4):486–504 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosteller F, Colditz GA. Understanding research synthesis (meta-analysis). Annu Rev Public Health. 1996;17:1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander M, Grumbach K, Remy L, Rowell R, Massie BM. Congestive heart failure hospitalizations and survival in California: patterns according to race/ethnicity. Am Heart J. 1999;137(5):919–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Assassi S, Del Junco D, Sutter Ket al. Clinical and genetic factors predictive of mortality in early systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(10):1403–1411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brogan TV, Thiagarajan RR, Rycus PT, Bartlett RH, Bratton SL. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults with severe respiratory failure: a multi-center database. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(12):2105–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown LS, Jr, Siddiqui NS, Chu AF. Natural history of HIV-1 infection and predictors of survival in a cohort of HIV-1 seropositive injecting drug users. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88(1):37–42 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bush D, Martin LW, Leman R, Chandler M, Haywood LJ. Atrial fibrillation among African Americans, Hispanics and Caucasians: clinical features and outcomes from the AFFIRM trial. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(3):330–339 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen LM, Li G, Reitzel LRet al. Matched-pair analysis of race or ethnicity in outcomes of head and neck cancer patients receiving similar multidisciplinary care. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2009;2(9):782–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen CJ, Iwane MK, Palensky JBet al. A national HIV community cohort: design, baseline, and follow-up of the AmFAR Observational Database. American Foundation for AIDS Research Community-Based Clinical Trials Network. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(9):779–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen MG, Granger CB, Ohman EMet al. Outcome of Hispanic patients treated with thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: results from the GUSTO-I and III trials. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPA for Occluded Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34(6):1729–1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper-DeHoff RM, Aranda JM, Jr, Gaxiola Eet al. Blood pressure control and cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk Hispanic patients–findings from the International Verapamil SR/Trandolapril Study (INVEST). Am Heart J. 2006;151(5):1072–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cromwell J, McCall NT, Burton J, Urato C. Race/ethnic disparities in utilization of lifesaving technologies by Medicare ischemic heart disease beneficiaries. Med Care. 2005;43(4):330–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham WE, Mosen DM, Morales LS, Andersen RM, Shapiro MF, Hays RD. Ethnic and racial differences in long-term survival from hospitalization for HIV infection. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2000;11(2):163–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Echols MR, Mahaffey KW, Banerjee Aet al. Racial differences among high-risk patients presenting with non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (results from the SYNERGY trial). Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(3):315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eden SV, Meurer WJ, Sanchez BNet al. Gender and ethnic differences in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurology. 2008;71(10):731–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feinglass J, Sohn MW, Rodriguez H, Martin GJ, Pearce WH. Perioperative outcomes and amputation-free survival after lower extremity bypass surgery in California hospitals, 1996-1999, with follow-up through 2004. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50(4):776–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernández M, Alarcon GS, McGwin G, Jret al. Using the Short Form 6D, as an overall measure of health, to predict damage accrual and mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: XLVII, results from a multiethnic US cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(6):986–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frankenfield DL, Rocco MV, Roman SH, McClellan WM. Survival advantage for adult Hispanic hemodialysis patients? Findings from the end-stage renal disease clinical performance measures project. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(1):180–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freedman DM, Looker AC, Chang SC, Graubard BI. Prospective study of serum vitamin D and cancer mortality in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(21):1594–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez SL, O’Malley CD, Stroup A, Shema SJ, Satariano WA. Longitudinal, population-based study of racial/ethnic differences in colorectal cancer survival: impact of neighborhood socioeconomic status, treatment and comorbidity. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gortmaker SL, Hughes M, Cervia Jet al. Effect of combination therapy including protease inhibitors on mortality among children and adolescents infected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(21):1522–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartmann A, Rundek T, Mast Het al. Mortality and causes of death after first ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Neurology. 2001;57(11):2000–2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harzke AJ, Baillargeon J, Paar DP, Pulvino J, Murray OJ. Chronic liver disease mortality among male prison inmates in Texas, 1989-2003. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1412–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Havranek EP, Froshaug DB, Emserman CDet al. Left ventricular hypertrophy and cardiovascular mortality by race and ethnicity. Am J Med. 2008;121(10):870–875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Helzner EP, Scarmeas N, Cosentino S, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y. Survival in Alzheimer disease: a multiethnic, population-based study of incident cases. Neurology. 2008;71(19):1489–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henderson SO, Bretsky P, Henderson BE, Stram DO. Risk factors for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular death among African Americans and Hispanics in Los Angeles, California. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8(12):1163–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jokela M, Elovainio M, Singh-Manoux A, Kivimaki MIQ. Socioeconomic status, and early death: the US National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(3):322–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee DJ, Markides KS. Activity and mortality among aged persons over an eight-year period. J Gerontol. 1990;45(1):S39–S42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao Y, McGee DL, Cooper RS. Mortality among US adult Asians and Pacific Islanders: findings from the National Health Interview Surveys and the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(3):423–433 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin CC, Rogot E, Johnson NJ, Sorlie PD, Arias E. A further study of life expectancy by socioeconomic factors in the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(2):240–247 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mak KH, Bhatt DL, Shao Met al. Ethnic variation in adverse cardiovascular outcomes and bleeding complications in the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) study. Am Heart J. 2009;157(4):658–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Manoharan M, Ayyathurai R, de Los Santos R, Nieder AM, Soloway MS. Presentation and outcome following radical cystectomy in Hispanics with bladder cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2008;34(6):691–698, discussion 698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medina RA, Pugh JA, Monterrosa A, Cornell J. Minority advantage in diabetic end-stage renal disease survival on hemodialysis: due to different proportions of diabetic type? Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28(2):226–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mendenhall CL, Gartside PS, Roselle GA, Grossman CJ, Weesner RE, Chedid A. Longevity among ethnic groups in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Alcohol. 1989;24(1):11–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murthy BV, Molony DA, Stack AG. Survival advantage of Hispanic patients initiating dialysis in the United States is modified by race. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(3):782–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ostir GV, Goodwin JS. High anxiety is associated with an increased risk of death in an older tri-ethnic population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(5):534–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palmas W, Pickering TG, Teresi Jet al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and all-cause mortality in elderly people with diabetes mellitus. Hypertension. 2009;53(2):120–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Patel KV, Eschbach K, Ray LA, Markides KS. Evaluation of mortality data for older Mexican Americans: implications for the Hispanic paradox. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):707–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peralta CA, Shlipak MG, Fan Det al. Risks for end-stage renal disease, cardiovascular events, and death in Hispanic versus non-Hispanic white adults with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(10):2892–2899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perez EA, Gutierrez JC, Moffat FL, Jret al. Retroperitoneal and truncal sarcomas: prognosis depends upon type not location. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(3):1114–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perez MV, Yaw TS, Myers J, Froelicher VF. Prognostic value of the computerized ECG in Hispanics. Clin Cardiol. 2007;30(4):189–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Plurad DS, Lustenberger T, Kilday Pet al. The association of race and survival from sepsis after injury. Am Surg. 2010;76(1):43–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Robinson BM, Joffe MM, Pisoni RL, Port FK, Feldman HI. Revisiting survival differences by race and ethnicity among hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(10):2910–2918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sacco RL, Hauser WA, Mohr JP, Foulkes MA. One-year outcome after cerebral infarction in whites, blacks, and Hispanics. Stroke. 1991;22(3):305–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sacco RL, Khatri M, Rundek Tet al. Improving global vascular risk prediction with behavioral and anthropometric factors. The multiethnic NOMAS (Northern Manhattan Cohort Study). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(24):2303–2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schupf N, Costa R, Luchsinger J, Tang MX, Lee JH, Mayeux R. Relationship between plasma lipids and all-cause mortality in nondemented elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BSet al. Perioperative mortality and long-term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2010;303(10):959–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Serna DS, Lee SJ, Zhang MJet al. Trends in survival rates after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute and chronic leukemia by ethnicity in the United States and Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(20):3754–3760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shaw LJ, Shaw RE, Merz CNet al. Impact of ethnicity and gender differences on angiographic coronary artery disease prevalence and in-hospital mortality in the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Circulation. 2008;117(14):1787–1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silverberg MJ, Leyden W, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Horberg MA. Race/ethnicity and risk of AIDS and death among HIV-infected patients with access to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1065–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smyth B, Hoffman V, Fan J, Hser YI. Years of potential life lost among heroin addicts 33 years after treatment. Prev Med. 2007;44(4):369–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stefanidis D, Pollock BH, Miranda Jet al. Colorectal cancer in Hispanics: a population at risk for earlier onset, advanced disease, and decreased survival. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29(2):123–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steffen-Batey L, Nichaman MZ, Goff DC, Jret al. Change in level of physical activity and risk of all-cause mortality or reinfarction: The Corpus Christi Heart Project. Circulation. 2000;102(18):2204–2209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sudano JJ, Baker DW. Explaining US racial/ethnic disparities in health declines and mortality in late middle age: the roles of socioeconomic status, health behaviors, and health insurance. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(4):909–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Swenson CJ, Trepka MJ, Rewers MJ, Scarbro S, Hiatt WR, Hamman RF. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(10):919–928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tedaldi EM, Absalon J, Thomas AJ, Shlay JC, van den Berg-Wolf M. Ethnicity, race, and gender. Differences in serious adverse events among participants in an antiretroviral initiation trial: results of CPCRA 058 (FIRST Study). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(4):441–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Waring SC, Doody RS, Pavlik VN, Massman PJ, Chan W. Survival among patients with dementia from a large multi-ethnic population. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19(4):178–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wei M, Valdez RA, Mitchell BD, Haffner SM, Stern MP, Hazuda HP. Migration status, socioeconomic status, and mortality rates in Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites: the San Antonio Heart Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6(4):307–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wolf M, Betancourt J, Chang Yet al. Impact of activated vitamin D and race on survival among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(7):1379–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Young BA, Maynard C, Boyko EJ. Racial differences in diabetic nephropathy, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in a national population of veterans. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(8):2392–2399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SCet al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(3):638–641 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Orwin RG. A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. J Educ Stat. 1983;8(2):157–159 [Google Scholar]

- 79.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295(6):676–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Begg CB. Publication bias. : Cooper H, Hedges LV, The Handbook of Research Synthesis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1994:399–409 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Duval S, Tweedie R. A non-parametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95(449):89–98 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cooper HM, Lindsay JJ. Research synthesis and meta-analysis. : Bickman L, Rog DJ, Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1998:315–337 [Google Scholar]

- 85.Borrell LN, Lancet EA. Race/ethnicity and all-cause mortality in US adults: revisiting the Hispanic paradox. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):836–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ruiz JM, Steffen P. Latino Health. : Friedman HS, The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011:805–823 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ruiz JM, Steffen P, Prather CC. Socioeconomic status and health. : Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, Handbook of Health Psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2012:539–568 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gallo LC, de Los Monteros KE, Allison Met al. Do socioeconomic gradients in subclinical atherosclerosis vary according to acculturation level? Analyses of Mexican-Americans in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(7):756–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Blue L, Fenelon A. Explaining low mortality among US immigrants relative to native-born Americans: the role of smoking. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(3):786–793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57(14):1–134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Borrell LN, Crawford ND. All-cause mortality among Hispanics in the United States: exploring heterogeneity by nativity status, country of origin, and race in the National Health Interview Survey-linked Mortality Files. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19(5):336–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]