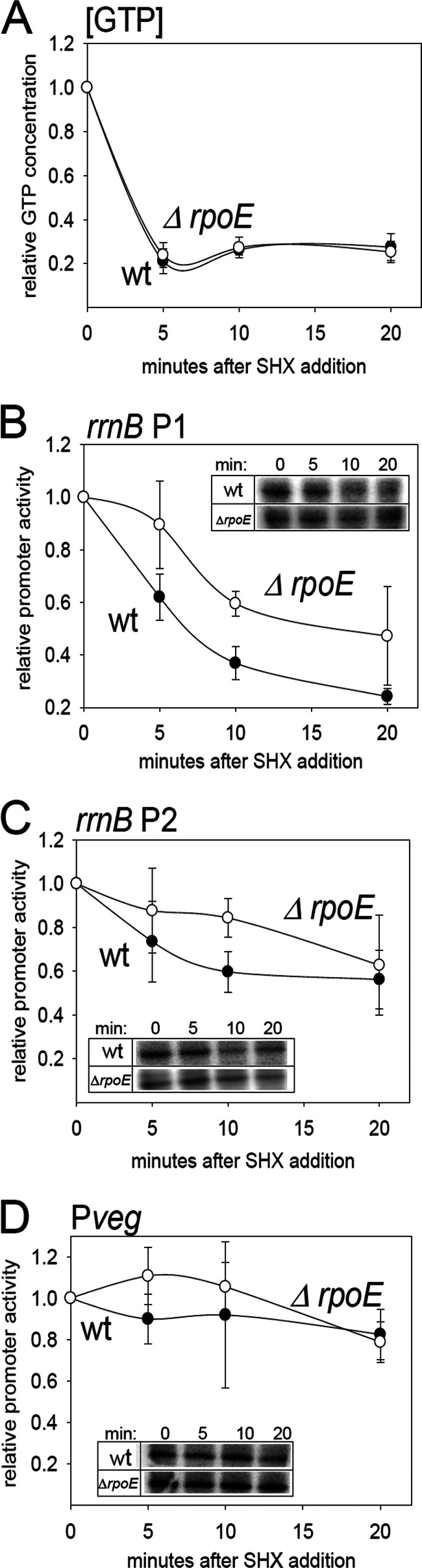

Fig 4.

δ affects the kinetics of promoter response to amino acid starvation in vivo. (A) Quantitation of the relative changes in the intracellular GTP concentration in the wt strain (RLG7554) and the ΔrpoE strain (LK642). The cells were growing in a defined MOPS-buffered medium with all 20 amino acids in the presence of 32P. At time zero, SHX was added, inducing starvation for amino acids. At time zero (before the addition of SHX) and at indicated time intervals, aliquots of the cells were withdrawn and NTPs extracted and quantified. The graph shows the averages from two independent experiments. The bars indicate the range. (B) Kinetics of the rrnBp1 promoter response to amino acid starvation in wt (filled circles; RLG7554) and ΔrpoE (open circles; LK642) strains. The amino acid starvation was induced as described for panel A. At selected time intervals, RNA was extracted, reverse transcribed, and quantified (see Materials and Methods for details). The amount of the mRNA that originated from the rrnBp1-marker gene fusion was used as a measure of the relative promoter activity. (C) Kinetics of the rrnBp2 promoter response to amino acid starvation in wt (filled circles; RLG7553) and ΔrpoE (open circles; LK293) strains. (D) Kinetics of the Pveg promoter response to amino acid starvation in wt (filled circles; RLG7555) and ΔrpoE (open circles; LK643) strains. The insets show representative reverse-transcribed 5′-end portions of the lacZ mRNAs that originated from the tested promoters.