The mammalian target of rapamycin, mTOR kinase is a compelling cancer drug target. mTOR, which exists in two distinct multi-protein complexes (mTORC1 and mTORC2), transduces growth factor receptor signals via the PI3K pathway and integrates them with nutrient and energy status to control a diverse array of functions including protein translation, glycolysis and lipogenesis.1 Thus, mTOR serves as a critical regulatory node in the cell, controlling proliferation. In cancer, mutations in growth factor receptor signaling pathways persistently activate mTOR, supporting unrestrained tumor growth. The highly lethal form of adult brain cancer, glioblastoma (GBM), is one characteristic example. PI3K pathway activating mutations in growth factor receptor signaling pathways occur in nearly 90% of GBMs,2 with frequent amplification and mutation of EGFR and deletion and mutation of PTEN,2 providing compelling rationale for mTOR inhibitor therapy. However to date, attempts to target mTOR in GBM patients have failed. The allosteric mTOR inhibitor rapamycin and its analogs show no clinical benefit, failing to fully suppress mTORC1 signaling and paradoxically reactivating Akt signaling in tumor tissue3 including through an mTORC2-dependent feedback loop.4 ATP-competitive mTOR kinase inhibitors and dual PI3K/mTOR kinase inhibitors that can potentially suppress both mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling have moved forward into early clinical testing in GBM. However, it is anticipated that other mechanisms of resistance may arise.

In a recent paper, we showed that the promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML), promotes a highly unexpected, but potentially targetable mechanism of mTOR inhibitor resistance in GBM.5 PML is the core component of a nuclear substructure (PML nuclear bodies) that contains more than 70 proteins to enact a diverse array of functions including regulation of gene transcription and protein modification.6 PML’s relevance to cancer was first highlighted by its identification as part of the PML-RARα fusion oncogene in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Remarkably, adding arsenic trioxide (ATO), which was derived from an ancient Chinese herbal formula and was subsequently shown to target PML for degradation through SUMOylation-dependent ubiquitination, induces complete remission or cure in this previously deadly form of cancer, providing one of the most compelling success stories for targeted cancer therapy and suggesting the potential targetability of PML in the clinic.7 PML also appears to play an important role in other cancers. In chronic myeloid leukemia, PML initiates a quiescent state, enabling tumor to evade cytotoxic chemotherapy, which can be overcome by the addition of ATO.8

In solid cancers, the role of PML and its impact on treatment response is less certain. We hypothesized that PML could render GBMs resistant to mTOR targeted therapies by inducing quiescence through suppression of mTOR signaling. Immunohistochemical analysis of GBM clinical samples demonstrated that PML expression was inversely correlated with mTOR signaling and with Ki67 labeling, a measure of tumor cell proliferation. Mechanistically confirming these observations, overexpression of PML suppressed mTOR signaling and limited proliferation in GBM cells. Further, in glioblastoma cell lines, xenograft models and most importantly in tumor tissue from patients treated with rapamycin or erlotinib, mTOR inhibition resulted in potent upregulation of PML levels. Genetic depletion of PML by siRNA knockdown, or treatment with low dose ATO sensitized GBM cells mTOR inhibitor-mediated tumor cell death, converting the normal cytostatic response to an apoptotic one. Most importantly, in tumor xenografts, ATO and the mTOR kinase inhibitor pp242 were relatively ineffective when given alone, but potently synergized, suppressing PML upregulation and causing massive tumor cell death.5

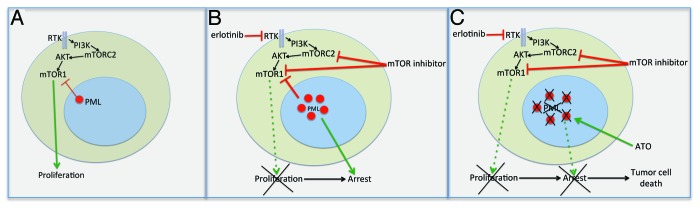

These results raise a number of intriguing questions. mTOR is a compelling drug target in multiple solid cancer types. Does PML upregulation similarly contribute to mTOR inhibitor resistance in other cancer types, and if so, is it similarly targetable by ATO? mTOR and PML are both critical regulatory nodes in the cell, each functioning as a rheostat to “tune” and integrate complex signaling cascades. What are the mechanisms by which PML becomes upregulated in response to mTOR inhibition and do they present a potential drug targets? PML is considered to be a tumor suppressor, but its role in promoting cancer drug resistance, demonstrates a more nuanced function, hindering or aiding tumor survival depending on genetic and biochemical context. Well-designed clinical trials combining mTOR inhibitors with ATO may improve the outcome for GBM patients and are likely to shed new light on the role of PML in cancer, particularly with regard to its interaction with mTOR. (Fig. 1)

Figure 1. PML mediates resistance to mTOR targeted therapies in GBM, which is reversed by ATO. (A) Schematic diagram showing that persistent mTOR signaling promotes tumor cell proliferation, while PML opposes it. (B) In GBMs treated with mTOR inhibitors or EGFR inhibitors such as erlotinib that also block mTOR signaling, PML is upregulated, promoting tumor cell arrest. (C) ATO, which leads to degradation of PML protein, synergizes with mTOR inhibitors, potently causing tumor cell death.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/24747

References

- 1.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cloughesy TF, Yoshimoto K, Nghiemphu P, Brown K, Dang J, Zhu S, et al. Antitumor activity of rapamycin in a Phase I trial for patients with recurrent PTEN-deficient glioblastoma. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tanaka K, Babic I, Nathanson D, Akhavan D, Guo D, Gini B, et al. Oncogenic EGFR signaling activates an mTORC2-NF-κB pathway that promotes chemotherapy resistance. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:524–38. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwanami A, Gini B, Zanca C, Matsutani T, Assuncao A, Nael A, et al. PML mediates glioblastoma resistance to mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-targeted therapies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4339–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217602110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carracedo A, Ito K, Pandolfi PP. The nuclear bodies inside out: PML conquers the cytoplasm. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:360–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu J, Liu YF, Wu CF, Xu F, Shen ZX, Zhu YM, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of all-trans retinoic acid/arsenic trioxide-based therapy in newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3342–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813280106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito K, Bernardi R, Morotti A, Matsuoka S, Saglio G, Ikeda Y, et al. PML targeting eradicates quiescent leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 2008;453:1072–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]