Abstract

The Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB) is the international collaboration that manages the deposition, processing and distribution of the PDB archive. The wwPDB’s mission is to maintain a single archive of macromolecular structural data that are freely and publicly available to the global community. Its members [RCSB PDB (USA), PDBe (Europe), PDBj (Japan), and BMRB (USA)] host data-deposition sites and mirror the PDB ftp archive. To support future developments in structural biology, the wwPDB partners are addressing organizational, scientific, and technical challenges.

Keywords: Protein Data Bank, structural biology, archive

INTRODUCTION

Since 1971, 3D data for experimentally determined structures of proteins and nucleic acids have been deposited and archived in the Protein Data Bank (PDB).1 Established at Brookhaven National Laboratory2 with seven crystal structures, the archive has grown to contain more than 83,000 entries today, determined using X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, 3D electron microscopy, and hybrid methods.

The archive is managed by the Worldwide Protein Data Bank organization (wwPDB), whose mission is to ensure that a single, global PDB data archive is and will remain freely and publicly available.3 The wwPDB was established since the archive represents global science and its management requires collaborative international efforts. Its members are organizations that act as deposition, processing and distribution centers for PDB data: Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) PDB (USA), Protein Data Bank in Europe (PDBe), Protein Data Bank Japan (PDBj), and BioMagResBank (BMRB, USA). The wwPDB partners collaborate on all policy and technical issues surrounding the maintenance of the archive (deposition, distribution, format issues, validation, remediation, etc.), while creating independent tools and resources that deliver the data to users (Table I).4–7 An advisory committee, comprised of experts in structural biology and bioinformatics, meets annually.

Table I.

wwPDB Collaborations

| Activities Focus | Results |

|---|---|

| Data deposition | Deposition and annotation procedures |

| Format standards | |

| Specialized data dictionaries | |

| Data deposition help desk | |

| Software development | |

| Archive support | Coordinated, weekly releases of PDB data |

| Yearly snapshots | |

| Archive quality | Regular reviews of data across the archive |

| Remediation efforts | |

| Validation standards | |

| Community outreach | Policy issues |

| Task Force meetings | |

| Workshops | |

| Journal interactions | |

| Symposia | |

| Presentations and exhibitions at scientific meetings |

The four wwPDB members collaborate on several activities that support the existence of a single PDB archive of macromolecular data.

In this review we describe the past and current PDB together with the challenges it faces as well as plans for meeting these challenges.

PDB DATA: GROWTH AND CHALLENGES

As a 40-year-old global archive, the PDB reflects the development and current state of structural biology in terms of both science and technology. In 1971, X-ray crystallography was the only method available to determine structures of small globular proteins that were purified from natural sources. Data were collected on home sources with crystals mounted in capillaries. Film or diffractometers were used to measure the diffraction patterns. Multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR) was used to determine the phases using computers with orders of magnitude less capacity than modern machines. Models were built using brass parts and their coordinates were measured manually. Structures were usually not refined, and took a very long time to determine. Each year, only a few were deposited into the PDB. Once cloning methods were developed it became possible to express large quantities of material. Access to synchrotron sources and area detectors allowed data to be collected rapidly using intense sources of X-rays. Multiple-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) allowed for the direct determination of phases from proteins with anomalous scatterers. The structural genomics initiatives that began around the turn of the millennium promoted and implemented high-throughput structure determination where every step in the pipeline was optimized using automation and robotics. It became possible to determine structures in a matter of minutes or hours rather than months or years. All of these technological advances are reflected in the continuing growth of the number of structures deposited in the PDB.

Although X-ray crystallography remains the dominant method for structure determination, NMR-based structures now account for about 12% of the PDB archive. More recently, cryo-electron microscopy (EM) methods have been developed that allow structure determination of large macro-molecular machines. In 1990, the first EM-based entry was deposited in the PDB. In 2002, the EM Data Bank (EMDB) was founded as the primary archive of 3D EM maps.8 In 2012, the ftp archives of PDB and EMDB were joined to facilitate user access to EM maps and models.

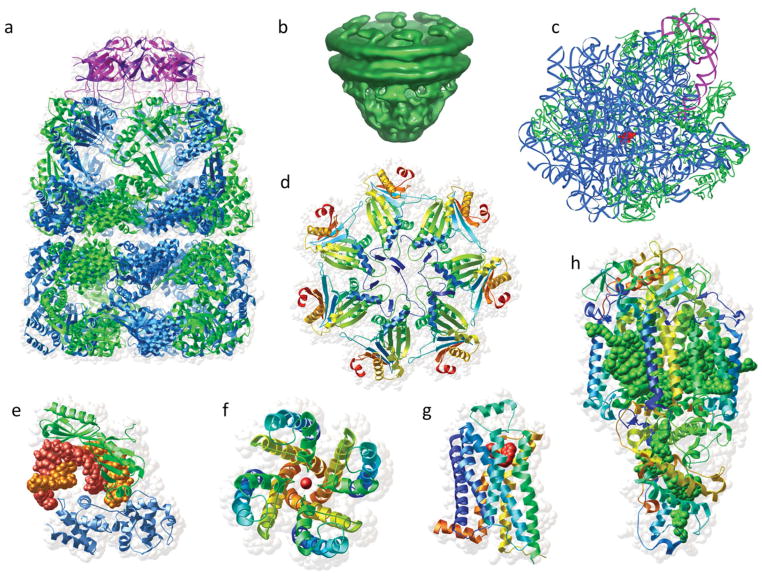

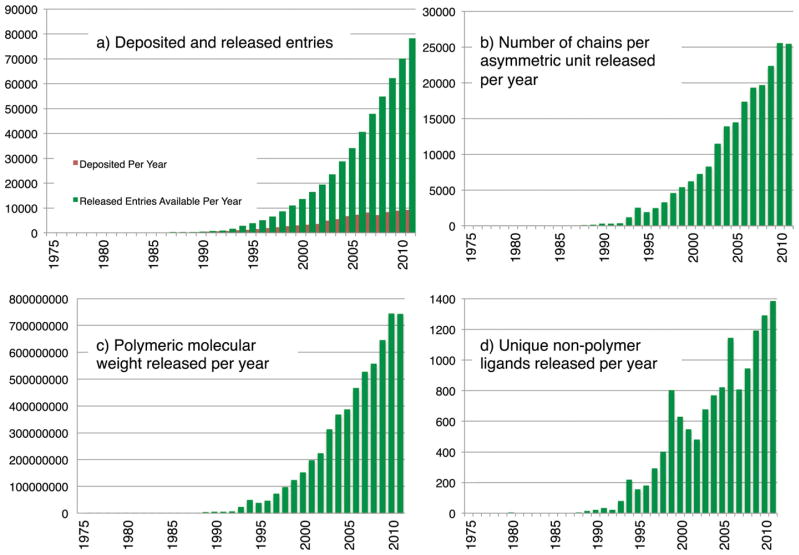

The diversity and complexity of structures archived in the PDB is ever increasing (Figure 1). In addition to single-chain globular proteins, the PDB now contains large complexes, some of which contain more than 50 polymer chains of various combinations of proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecule ligands (Figure 2). The average number of residues per entry has grown from ~230 in the 1970s to almost 800 in 2011.

FIGURE 1.

Some examples of the diversity and complexity of modern structural biology: a) GroEL-GroES from PDB entry 1pcq18; b) the nuclear pore complex (EMD-1097)19; c) ribosome from 3pio20; d) archaeal proteasome gate from 2ku121; e) transcription factor IIB (TFIIB)/TATA box-binding protein from 1vol22; f) potassium channel from 1bl823; g) beta-adrenergic GPCR from 2rh124; h) photosynthetic reaction center from 1prc.25

FIGURE 2.

Growth of the PDB archive: a) deposited and all released structures over time; b) number of chains per asymmetric unit released per year; c) polymeric molecular weight released per year; d) number of unique non-polymer ligands released per year.

A very important factor in the growth of the PDB has been the change in attitudes regarding data sharing. In 1971, the incentives to deposit data in the PDB were very practical: by putting data in the archive, depositors would ensure that the data would not get lost. The task of distributing data resident on magnetic tapes to interested parties located around the world became the job of the PDB. In spite of these conveniences, it was not the norm to deposit data. It wasn’t until the 1980s that several community groups began to establish guidelines for data sharing. Once published, the funding agencies and the journals began to adopt these guidelines. Today, structure deposition into the PDB is a prerequisite for publication in virtually every journal. These scientific, technological, and cultural changes have driven the continual growth of the PDB (Figure 2).

Changes in science and technology have also necessitated changes in the way data are represented in the archive. For instance, atom nomenclature now conforms to IUPAC and IUBMB standards. New content associated with PDB entries defines quaternary structure and symmetry. Since 2005, periodic reviews of the entire archive have prompted remediation efforts that bring all the data to the same standard.10,11 In addition, validation methods developed by the community have been adopted for the PDB. The requirement of depositing experimental data (structure factors and NMR restraints) along with the coordinate model in 2008 has made it possible to review the data and have much better quality assurance. In 2008, an X-ray Validation Task Force (VTF) was established to assess best practices in validation. The VTF has formulated a set of recommendations for validation procedures that are being implemented in the PDB deposition and annotation pipeline.12,13 Task forces for NMR spectroscopy, Electron Microscopy14 and Small Angle Scattering have also been established and work is underway to recommend or develop validation procedures for these methods.

MEETING TECHNICAL CHALLENGES

As structures began to push the limits of the tools and resources used to deposit, annotate, and store PDB data, it became clear that these tools and resources would need to evolve. It also became clear that review and remediation of the data across the archive was not a one-off project, but something that would need to be done on an ongoing basis. The collaboration of the wwPDB partners on all aspects of data representation and processing made it possible to design and develop a new unified system for data deposition, annotation and remediation.

This new wwPDB Deposition and Annotation (D&A) system will allow coordinate and experimental data produced by current structure-determination methods to be submitted to the PDB, EMDB and BMRB using a common interface. Requirements for the system were defined by all the wwPDB partners, taking into account the many years of experience they have in managing the data, while using the opportunity to streamline and improve various processes. Straightforward steps will be automated so that the focus of the annotation staff can be on difficult scientific problems. All structures will be validated during deposition, alerting the experimentalist to any problems or inconsistencies that need to be addressed urgently. wwPDB annotation staff will perform further annotation and full validation of the data. The actual annotation site will be assigned based on factors such as geography, scientific expertise, and current workload. The D&A system and procedures will also allow remediation of the archive with reliable tracking of the changes made to the data. It is expected that the D&A system will speed up data processing and result in entries of high quality.

A key aspect of the project has been the decision to make PDBx the exchange data format. PDBx is based on mmCIF and is much more expressive and software-accessible than the legacy PDB format.15,16 At a 2011 wwPDB workshop with the developers of key structure-determination software, it was agreed the PDBx will be adopted as the format used for deposition and as an exchange format between programs for macromolecular crystallography. Thus, the data that will come to the PDB will already be properly formatted thereby eliminating many sources of error.

MEETING ORGANIZATIONAL CHALLENGES

From its inception, the PDB has been a global archive and unlike other biological resources, it has remained singular and uniform. The wwPDB management structure ensures that all data centers conform to the same standards for formatting, annotation, and validation of the archival data. Policies are continually reviewed by the organization to make certain that they adequately address evolving issues. All this guarantees that the community of users is provided with reliable and consistent data. The operation of the wwPDB requires a considerable amount of effort and collaboration from the member organizations, each of which is independently funded and on different funding cycles. Moreover, the wwPDB collaboration itself does not receive any dedicated funds.

A charitable wwPDB Foundation was recently formed to support education outreach, continued collaboration with the community on standards, and meetings related to our strategic goals. The first community outreach project of this new organization was the PDB40 symposium that commemorated the 40th anniversary of the archive.17

THE FUTURE

There is no doubt that the number, size, and complexity of the structures in the PDB will continue to grow. The same is true for the armament of methods that will be brought to bear on determining structures. Hybrid methods, which use a variety of biophysical, biochemical, and modeling techniques, will be used increasingly to determine the shapes of complex molecular machines. The challenge to the wwPDB partners is to work with community experts to ensure that the PDB continues to provide data of the highest quality. As has been the case for the last 40 years, all this work will have to be done in an unpredictable funding climate. As long as the science contained within the PDB remains as vital as it is, we predict that the PDB will continue to thrive.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsors: RCSB PDB by NSF DBI 0829586, NIGMS, DOE, NLM, NCI, NINDS, NIDDK, PDBe by EMBL-EBI, Wellcome Trust, BBSRC, NIGMS, and EU; PDBj by NBDC-JST, BMRB by NLM

References

- 1.Berman H. Acta Crystallogr A: Foundations of Crystallography. 2008;64:88–95. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307035623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein FC, Koetzle TF, Williams GJB, Meyer EF, Jr, Brice MD, Rodgers JR, Kennard O, Shimanouchi T, Tasumi M. J Mol Biol. 1977;112:535–542. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(77)80200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berman HM, Henrick K, Nakamura H. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:980. doi: 10.1038/nsb1203-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berman HM, Westbrook JD, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velankar S, Alhroub Y, Best C, Caboche S, Conroy MJ, Dana JM, Fernandez Montecelo MA, van Ginkel G, Golovin A, Gore SP, Gutmanas A, Haslam P, Hendrickx PM, Heuson E, Hirshberg M, John M, Lagerstedt I, Mir S, Newman LE, Oldfield TJ, Patwardhan A, Rinaldi L, Sahni G, Sanz-Garcia E, Sen S, Slowley R, Suarez-Uruena A, Swaminathan GJ, Symmons MF, Vranken WF, Wainwright M, Kleywegt GJ. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D445–D452. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinjo AR, Suzuki H, Yamashita R, Ikegawa Y, Kudou T, Igarashi R, Kengaku Y, Cho H, Standley DM, Nakagawa A, Nakamura H. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D453–D460. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulrich EL, Akutsu H, Doreleijers JF, Harano Y, Ioannidis YE, Lin J, Livny M, Mading S, Maziuk D, Miller Z, Nakatani E, Schulte CF, Tolmie DE, Kent Wenger R, Yao H, Markley JL. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D402–D408. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tagari M, Newman R, Chagoyen M, Carazo JM, Henrick K. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:589. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henrick K, Feng Z, Bluhm WF, Dimitropoulos D, Doreleijers JF, Dutta S, Flippen-Anderson JL, Ionides J, Kamada C, Krissinel E, Lawson CL, Markley JL, Nakamura H, Newman R, Shimizu Y, Swaminathan J, Velankar S, Ory J, Ulrich EL, Vranken W, Westbrook J, Yamashita R, Yang H, Young J, Yousufuddin M, Berman HM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D426–D433. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson CL, Dutta S, Westbrook JD, Henrick K, Berman HM. Acta Cryst. 2008;D64:874–882. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908017393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Read RJ, Adams PD, Arendall WB, III, Brunger AT, Emsley P, Joosten RP, Kleywegt GJ, Krissinel EB, Lutteke T, Otwinowski Z, Perrakis A, Richardson JS, Sheffler WH, Smith JL, Tickle IJ, Vriend G, Zwart PH. Structure. 2011;19:1395–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gore S, Velankar S, Kleywegt GJ. Acta Crystallographica. 2012;D68:478–483. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911050359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson R, Sali A, Baker ML, Carragher B, Devkota B, Downing KH, Egelman EH, Feng Z, Frank J, Grigorieff N, Jiang W, Ludtke SJ, Medalia O, Penczek PA, Rosenthal PB, Rossmann MG, Schmid MF, Schroder GF, Steven AC, Stokes DL, Westbrook JD, Wriggers W, Yang H, Young J, Berman HM, Chiu W, Kleywegt GJ, Lawson CL. Structure. 2012;20:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzgerald PMD, Westbrook JD, Bourne PE, McMahon B, Watenpaugh KD, Berman HM. In: International Tables for Crystallography. Hall SR, McMahon B, editors. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2005. pp. 295–443. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westbrook JD, Fitzgerald PMD. In: Structural Bioinformatics. 2. Bourne PE, Gu J, editors. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. pp. 271–291. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berman HM, Kleywegt GJ, Nakamura H, Markley JL. Structure. 2012;20:391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaudhry C, Farr GW, Todd MJ, Rye HS, Brunger AT, Adams PD, Horwich AL, Sigler PB. EMBO J. 2003;22:4877–4887. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck M, Forster F, Ecke M, Plitzko JM, Melchior F, Gerisch G, Baumeister W, Medalia O. Science. 2004;306:1387–1390. doi: 10.1126/science.1104808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belousoff MJ, Shapira T, Bashan A, Zimmerman E, Rozenberg H, Arakawa K, Kinashi H, Yonath A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2717–2722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019406108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Religa TL, Sprangers R, Kay LE. Science. 2010;328:98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1184991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikolov DB, Chen H, Halay ED, Usheva AA, Hisatake K, Lee DK, Roeder RG, Burley SK. Nature. 1995;377:119–128. doi: 10.1038/377119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doyle DA, Morais Cabral J, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cherezov V, Rosenbaum DM, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SG, Thian FS, Kobilka TS, Choi HJ, Kuhn P, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, Stevens RC. Science. 2007;318:1258–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.1150577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deisenhofer J, Epp O, Sinning I, Michel H. J Mol Biol. 1995;246:429–457. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]