Abstract

Objective

To test the specificity of the association between tobacco advertising and youth smoking initiation.

Design

Longitudinal survey with a 30 month interval.

Setting

21 public schools in three German states.

Participants

A total of 1320 sixth-to-eighth grade students who were never-smokers at baseline (age range at baseline, 10–15 years; mean, 12.3 years).

Exposures

Exposure to tobacco and non-tobacco advertisements was measured at baseline with images of six tobacco and eight non-tobacco advertisements; students indicated the number of times they had seen each ad and the sum score over all advertisements was used to represent inter-individual differences in the amount of advertising exposure.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Established smoking, defined as smoked >100 cigarettes during the observational period, and daily smoking at follow-up. Secondary outcome measures were any smoking and smoking in the last 30 days.

Results

During the observation period, 5% of the never-smokers at baseline smoked more than 100 cigarettes and 4.4% were classified as daily smokers. After controlling for age, gender, socioeconomic status, school performance, television screen time, personality characteristics and smoking status of peers and parents, each additional 10 tobacco advertising contacts increased the adjusted relative risk for established smoking by 38% (95% CI 16% to 63%; p<0.001) and for daily smoking by 30% (95% CI 3% to 64%; p<0.05). No significant association was found for non-tobacco advertising contact.

Conclusions

The study confirms a content-specific association between tobacco advertising and smoking behaviour and underlines that tobacco advertising exposure is not simply a marker for adolescents who are generally more receptive or attentive towards marketing.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH

Article summary.

Article focus

High exposure to tobacco advertising might just be an indicator of high advertising exposure in general.

In this study, we compare the potential of tobacco advertising versus non-tobacco advertising exposure in predicting established and daily smoking of formerly never-smoking German adolescents.

Key messages

Exposure to tobacco advertisements predicted established smoking and daily smoking, whereas exposure to non-tobacco advertising did not.

The study also shows that advertising allowed under partial bans still reaches adolescents.

Strengths and limitations of this study

It is one of the few studies to test the specificity of the association between tobacco advertising and smoking.

The long follow-up period with smoking outcomes is strongly predictive of an individual becoming an addicted smoker.

A high dropout rate and attrition bias are the limiting factors of this study.

Introduction

Tobacco companies were among the first companies to use integrated marketing strategies, and their products have long been among the most heavily marketed products in the USA and worldwide.1 The tobacco industry still denies that their marketing is targeted at young people. According to the industry, the purpose of tobacco advertising is to maintain and increase market shares of adult consumers.2 In contrast, empirical research indicates that adolescents are aware of, recognise and are influenced by tobacco marketing strategies. The US Surgeon General's 2012 comprehensive review of the tobacco marketing literature concluded that advertising and promotional activities by tobacco companies are key risk factors for the uptake to smoking in adolescents.3

A 2011 Cochrane review identified 19 longitudinal studies that followed up a total of over 29 000 subjects who were adolescents aged 18 or younger and were not regular smokers at baseline. In 18 of the 19 studies, the non-smoking adolescents, who were more aware of tobacco advertising or receptive to it, were more likely to experiment with cigarettes or become smokers at follow-up.4

Based on these research results, article 13 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control stipulates a comprehensive ban on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship.5 A number of countries all over the world follow these recommendations and have banned tobacco advertisements. However, other countries such as the USA and Germany have implemented considerably weaker tobacco marketing policies.6 Germany has banned tobacco advertisements in television, radio, newspapers and magazines, but there are still opportunities for the industry to promote their products: tobacco marketing is allowed at point of sale, on billboards and in cinemas before movies that show after 18:00. Brand extension, that is, the use of tobacco brand names for other products, is also allowed.

From a scientific point of view, the best way to study the effects of tobacco marketing would be a randomised controlled trial. But this kind of study design would be both unethical and impractical. Since experimental studies cannot be conducted, we have to rely on observational studies. Sir Austin Bradford Hill identified several criteria for evaluating causality in epidemiological studies.7 According to these criteria, the risk factor (eg, tobacco marketing) must clearly precede the hypothesised effect (eg, smoking uptake in young people). In addition, the association should be strong, consistent, expected from theory and specific.

The Cochrane review on the effects of tobacco advertising on young people4 listed our previous study8 9 as the only one that tested the specificity of tobacco advertising compared with advertisements of other consumer goods. Limitations of this study included (A) the short 9-month follow-up period, and (B) the outcome measure which defined smoking initiation during the observational period as any smoking including a few puffs. Clearly, not all adolescents who try smoking will go on to become addicted smokers. With the current study, we present findings from the same cohort, only for a much longer follow-up period (30 months). The longer follow-up period enables us to study established and daily smoking as outcomes in young people, outcomes that are more strongly predictive of becoming an addicted smoker.10

Methods

Study sample

In May 2008, we invited 120 randomly selected schools from three states of Germany (Brandenburg, Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein) to participate in a school-based survey. The German school system has different types of schools (Grundschule, Hauptschule, Realschule, Oberschule, Gemeinschaftsschule, Gymnasium) that mainly differ with regard to the academic skills of their students and graduation level. The selection was stratified by state and type of school, assuring a balanced representation of all school types of the respective states. Twenty-nine schools with 176 classes and 4195 sixth to eighth grade students agreed to participate after a 4-week recruitment interval. In September and October 2008, we surveyed a total of 174 classes with 3415 students (81.4% of the sampled students). Reasons for exclusion were either absence (2 classes, 134 students) or missing parental consent (646 students). From the 3415 students surveyed at baseline, 2346 were classified as never-smokers. Of these, 1320 (56.3%) could be reached again at the follow-up assessment in May/June 2011. Reasons for study dropout were loss of primary schools that end after sixth grade (7 schools, 14 classes, 194 students), refusal to participate at the follow-up assessment (1 school, 8 classes, 59 students) or class absence (24 classes, 291 students). Other reasons were unexplained absence on the day of data assessment or unmatchable student codes (482 students). The number of analysed never-smokers per school ranged from 3 to 232, and class-sizes ranged from 1 to 26.

Survey implementation

Data were collected through self-completed anonymous questionnaires during one school hour (45 min period), administered by trained research staff. Only students with written parental consent were qualified for participation, and parent consent forms were disseminated by class teachers 3 weeks prior to the baseline assessment. Students did not receive incentives for participation and irrespective of parental consent, all students were free to refuse participation (none refused). Class teachers assigned tasks for students who did not participate. After completion of the survey, questionnaires were placed in an envelope and sealed in front of the class. Students were assured that their individual information would not be seen by parents or teachers. To permit a linking of the baseline and follow-up questionnaires, students generated an anonymous seven-digit individual code, a procedure that had been tested in previous studies, slightly modified for this study.11 Implementation was approved by all Ministries of Cultural Affairs of the three involved states, and ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Kiel (Ref.: D 417/08).

Measures

Advertising exposure

Advertising exposure has been operationalised in numerous ways across studies.4 It has been measured both in terms of the physical presence of advertisements in individuals’ environments and in terms of the psychological processes underlying individuals’ memories for these advertisements.12 In the present study, we approximated the individual advertising contact frequency by providing masked coloured images of billboard advertisements for cigarettes and fixed-images of TV commercials for non-tobacco ads with all brand-identifying content digitally removed, asking the students to rate how often they had ever seen each ad extract (on a 4-point scale with scale points 0=‘never,’,1=‘1 to 4 times,’ 2=‘5 to 10 times’ and 3=‘more than 10 times’). The answers were postcoded as 0=0, 1=2.5, 2=7.5 and 3=11 and summed up to create the tobacco and non-tobacco ad scales, respectively.

The images included six cigarette brands, and eight ‘control’ ads for products that included sweets, clothes, mobile phones and cars. The following cigarette brands were included in the survey (with the ad theme or cue in parentheses): (1) Marlboro (cowboy; horses); (2) F6 (sunrise); (3) Gauloises (couple); (4) Pall Mall (Empire State Building); (5) L&M (couple); (6) Lucky Strike (cigarette packs). These six cigarette brands are among the eight most popular cigarette brands in Germany.13 For other commercial products, the following ads were included in the survey (with the product type and ad theme or cue in parentheses): (1) Jack Wolfskin (trekking-clothing; climber); (2) Volkswagen (car; the performer Seal); (3) Tic Tac (candy; elevator); (4) Dr Best (toothbrush; tomato); (5) Kinder Pingui (chocolate bar; penguins); (6) T-Mobile (mobile phone; dog); (7) Spee (detergent; fox); (8) Toyota (car). Advertising selection was based on a pilot study on 28 tobacco and non-tobacco ads (110 students aged 11–16 years, mean age 13.6 years), selecting half of the ads that revealed neither the ceiling nor floor effects and had corrected item-test correlations above rit=0.40.

We assessed ad exposure to non-tobacco products to control for the propensity to be receptive or attentive to advertising in general, which could confound the relation between tobacco-specific advertising exposure and smoking behaviour.

Smoking behaviour

We assessed lifetime smoking experience by asking ‘how many cigarettes have you smoked in your life?’ (never-smoked, just a few puffs, 1–19 cigarettes, 20–100 cigarettes, >100 cigarettes).14 Students who indicated any smoking at baseline, even just a few puffs, were excluded from the analysis. Having smoked more than 100 cigarettes at the follow-up assessment was defined as being an established smoker. Current smoking frequency was measured by asking, ‘how often do you smoke at present?’ to which respondents could answer, ‘I don't smoke,’ ‘less than once a month,’ ‘at least once a month, but not weekly,’ ‘at least once a week, but not daily,’ or ‘daily.’ For the present analysis, this variable was dichotomised into daily and non-daily smoking. To account for different smoking susceptibility in never-smokers at baseline, we also assessed future use intentions (‘do you think you will ever smoke in the future?’) and refusal intentions (‘if one of your friends offered you a cigarette, would you take it?’), with response categories ‘definitely not’, ‘probably not’, ‘probably yes’, and ‘definitely yes’.15

Covariates

Covariate measures were derived from studies that focused on risk factors of adolescent tobacco use, to control for confounding variables that would be theoretically related to ad exposure and the smoking measures.16–18

Sociodemographics: age, gender, study region and socioeconomic status (SES); SES of the students was approximated with a combination of student and class teacher ratings: students answered three items of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) cultural and social capital assessment,19 asking for the number of books in the household (five-point scale from 0=‘none’ to 4=‘more than 100’) and parenting characteristics (‘my parents always know where I am’ and ‘my parents know other parents from my school’), class teachers filled out an 11-item school evaluation sheet related to SES of their students (examples: ‘most students of the school live in families with financial problems’, ‘most students of the school come from underprivileged families’, ‘our school has a good reputation’, scale range from 0=‘not true at all’ to 3=‘totally true’, Cronbach's α=0.85); student and teacher ratings positively correlated r=0.57, α=0.72.

Personal characteristics: self-reported school performance (‘how would you describe your grades last year?,’ scale points ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘average’, ‘below average’); average TV screen time (‘how many hours do you usually watch TV in your leisure time?’, scale points: ‘none’, ‘about half an hour’, ‘about an hour’, ‘about 2 h’, ‘about 3 h’, ‘about 4 h’, ‘more than 4 h a day’); rebelliousness and sensation-seeking, assessed with four items combined into a single index, with higher scores indicating greater propensity for rebelliousness and sensation seeking20 (‘I get in trouble in school’; ‘I do things my parents wouldn't want me to do’; ‘I like scary things’; ‘I like to do dangerous things’, scale points 0=‘not at all like me’, 1=‘a little like me’, 2=‘pretty much like me’, and 3=‘exactly like me’, Cronbach's α=0.76).

Social environment: parent smoking (0=‘no’, 1=‘yes, 2) and peer smoking (0=‘none’, 1=‘some, 2=‘most’, 3=‘all’). As mentioned above, we also controlled for the adolescent's ability to recall advertising in general with the non-tobacco ad scale.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were conducted with Stata V.12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). χ2 tests and t tests were performed to check whether the subjects included in the analysis differed systematically from those not reached at the follow-up assessment. Bivariate associations between the study variables were analysed using Spearman rank correlations. The multivariate associations between the amount of advertising exposure and smoking initiation were analysed with Poisson regressions. A Poisson regression allows for the presentation of adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% CIs for the relationship between exposure to advertising and smoking at follow-up, having the advantage of not being influenced by the prevalence of the exposure. IRRs were calculated for every 10 advertising contacts, indicating the relative increase in smoking incidence (established smoking and daily smoking) for each additional 10 contacts. The dichotomised outcome variables were regressed on advertising exposure after inclusion of all covariates and with clustered robust standard errors to account for intraclass correlations within schools. In a subsequent analysis, we repeated the Poisson regressions with advertising contact frequency being parsed into tertiles to account for the skewed distribution of tobacco advertising contact and to replicate the approach used in our previous analysis.9 Missing data were handled by listwise deletion.

Results

Descriptive statistics at baseline and attrition analysis

Table 1 gives the descriptive statistics for all interviewed never-smokers at baseline, for those lost to follow-up, and the final analysed sample, allowing comparisons of differences owing to attrition. Never-smokers lost to follow-up were of significantly younger age, more often male, had lower scores on the SES scale, rated their school performance more poorly, had higher scores in sensation seeking/rebelliousness and more often reported at least one parent who smoked. No differences were found with regard to tobacco or non-tobacco advertising contact.

Table 1.

Descriptive sample statistics at baseline and attrition analysis

| Baseline never-smokers (n=2346) (%) | Lost to follow-up (n=1026) (%) | Analysed sample (n=1320) (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||||

| Age at baseline, mean (SD) | 12.24 (1.01) | 12.16 (1.09) | 12.30 (0.93) | 0.001 |

| Gender (female) | 54.9 | 51.9 | 57.3 | 0.008 |

| SES (below median) | 51.1 | 60.6 | 43.8 | <0.001 |

| State | ||||

| Schleswig-Holstein | 41.6 | 39.8 | 43.0 | 0.279 |

| Hamburg | 28.4 | 29.1 | 27.8 | |

| Brandenburg | 30.0 | 31.1 | 29.2 | |

| Personal characteristics | ||||

| School performance | ||||

| Below average | 2.5 | 3.7 | 1.5 | <0.001 |

| Average | 33.7 | 37.8 | 30.6 | |

| Good | 49.9 | 44.9 | 53.9 | |

| Excellent | 13.9 | 13.6 | 14.0 | |

| TV screen time | ||||

| ≤30 min | 16.8 | 15.5 | 17.8 | 0.051 |

| 1–2 h | 59.5 | 58.8 | 60.1 | |

| 3–4 h | 19.0 | 19.8 | 18.3 | |

| >4 h | 4.7 | 5.9 | 3.8 | |

| Sens. seek. and rebelliousness, mean (SD), range 0–3 | 0.53 (0.50) | 0.56 (0.51) | 0.50 (0.49) | 0.010 |

| Social environment | ||||

| Peer smoking (none) | 71.7 | 71.5 | 71.9 | 0.858 |

| Parent smoking (no) | 53.3 | 49.3 | 56.4 | 0.001 |

| Advertising exposure | ||||

| Tobacco advertising, range 0–55 | ||||

| Low (<1) | 35.3 | 35.3 | 35.4 | 0.600 |

| Medium (1–10) | 38.7 | 39.7 | 38.0 | |

| High (>10) | 26.0 | 25.0 | 26.6 | |

| Non-tobacco advertising, range 0–88 | ||||

| Low (<35) | 39.8 | 40.8 | 39.0 | 0.469 |

| Medium (35–54) | 32.1 | 32.4 | 32.0 | |

| High (>54) | 28.1 | 26.8 | 29.0 | |

Sens. seek., sensation seeking; SES, socioeconomic status.

Smoking initiation during the observational period

Post-30 months of the baseline assessment, 436 never-smokers reported trying cigarette smoking, including a few puffs (33% incidence rate); 138 reported smoking in the past 30 days (10.5% incidence rate), 66 had smoked more than 100 cigarettes and were classified as established smokers (incidence rate 5%), and 58 reported daily smoking (incidence rate 4.4%). Daily smoking incidence was not significantly related to age (p=0.526) or sex (p=0.153), with 33% of the daily smokers at follow-up being 14 years of age or younger and 24% being 16 or older.

Exposure to advertisements at baseline

Table 2 gives contact frequencies (how often the students had seen the ad) for all advertised products at baseline. The cigarette ad with the highest contact frequency was Lucky Strike, for which about half of the sample reported at least one contact. The lowest tobacco ad contact frequency rate was found for F6, a regional German cigarette brand sold mainly in eastern Germany. Ad contact frequency for non-tobacco products was generally much higher than for tobacco products. For example, almost all students (96%) reported having seen the ad for Kinder Pingui, a chocolate bar. The range of the sum of contacts over all depicted advertisements was 0–55 (mean=7.9) for the tobacco ads, and 0–88 (mean=42.2) for the non-tobacco ads, also reflecting the lower number of tobacco ads (6 vs 8).

Table 2.

Contact frequency for tobacco and non-tobacco advertisings (n=1320 never-smokers at baseline)

| Seen at least once (%) | Seen more than 10 times (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco ads (product type) | ||

| Lucky Strike (cigarettes) | 49 | 13 |

| Marlboro (cigarettes) | 28 | 6 |

| Pall Mall (cigarettes) | 24 | 6 |

| Gauloises (cigarettes) | 19 | 2 |

| L&M (cigarettes) | 18 | 4 |

| F6 (cigarettes) | 12 | 1 |

| Non-tobacco ads (product type) | ||

| Kinder Pingui (sweet) | 96 | 71 |

| Tic Tac (candy) | 87 | 44 |

| Dr. Best (tooth brush) | 83 | 36 |

| T-Mobile (mobile phone) | 85 | 35 |

| Spee (detergent) | 76 | 24 |

| Volkswagen (car) | 50 | 14 |

| Toyota (car) | 54 | 10 |

| Jack Wolfskin (trekking-clothing) | 45 | 9 |

Zero order associations

Table 3 shows pairwise Spearman rank correlations between the study variables, demonstrating significant crude associations between the assessed covariates and smoking behaviour as well as between covariates and advertising contact, justifying their inclusion in the multivariate analyses. The highest correlation with all smoking outcomes was found for peer smoking, followed by tobacco advertising contact. There were some differences in the correlational pattern between tobacco and non-tobacco advertising contact. Compared to the amount of contact with tobacco ads, non-tobacco advertising exposure was stronger related to age, showing no association with gender, and also had a stronger correlation with SES, TV screen time and parental smoking. The zero-order correlation between tobacco and non-tobacco advertising contact indicated a proportion of about 20% shared variance.

Table 3.

Zero-order correlation matrix for all study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 2. Gender (0=female, 1=male) | 0.02 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 3. SES | −0.07* | 0.02 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 4. Region (0=west, 1=east) | 0.25*** | −0.01 | −0.10* | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 5. School performance | 0.11*** | 0.03 | −0.16*** | −0.05 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 6. TV screen time | 0.17*** | 0.07** | −0.30*** | 0.25*** | 0.15*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 7. Sensation seeking | 0.09*** | 0.24*** | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.16*** | 0.18*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 8. Peer smoking | 0.28*** | 0.02 | −0.22*** | 0.28*** | 0.15*** | 0.24*** | 0.24*** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 9. Parent smoking | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.26*** | 0.09*** | 0.11** | 0.22*** | 0.08** | 0.17*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 10. Tobacco ad exposure | 0.14*** | 0.13*** | 0.02 | −0.06* | 0.05 | 0.11** | 0.24*** | 0.13*** | 0.08** | 1.00 | ||||

| 11. Non-tobacco ad exposure | 0.20*** | 0.05 | −0.08** | 0.11** | 0.06* | 0.36*** | 0.21*** | 0.18*** | 0.18*** | 0.44*** | 1.00 | |||

| 12. Ever smoking | 0.15*** | 0.01 | −0.17*** | 0.14*** | 0.09** | 0.14*** | 0.18*** | 0.24*** | 0.13*** | 0.19*** | 0.15*** | 1.00 | ||

| 13. Past 30 days smoking | 0.09** | −0.02 | −0.12** | 0.08** | 0.06* | 0.12** | 0.15*** | 0.21*** | 0.14*** | 0.17*** | 0.12*** | 0.61*** | 1.00 | |

| 14. Established smoking (>100 cig.) | 0.07* | 0.09** | −0.07* | 0.08** | 0.05 | 0.10* | 0.12** | 0.16*** | 0.09*** | 0.13*** | 0.09** | 0.33*** | 0.51*** | 1.00 |

| 15. Daily smoking | 0.02 | 0.04 | −0.14*** | 0.08** | 0.07* | 0.10* | 0.09** | 0.14*** | 0.13*** | 0.08** | 0.03 | 0.30*** | 0.49*** | 0.75*** |

Italic figures represent significant associations.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

SES, socioeconomic status.

Association between advertising contact and smoking initiation

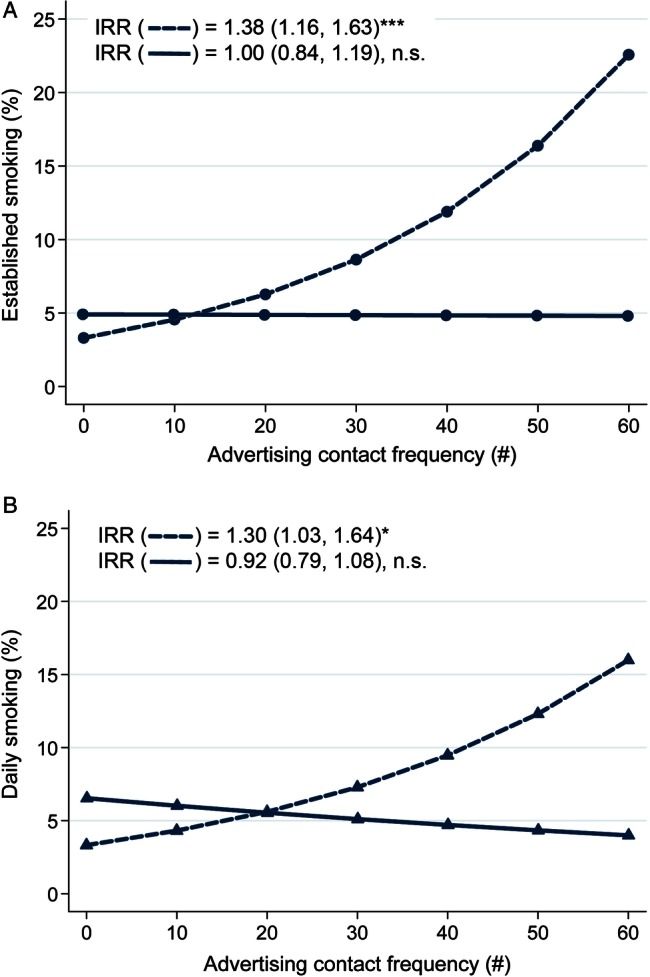

Figure 1A,B shows the adjusted predictions of established smoking and daily smoking based on the amount of tobacco and non-tobacco advertising contact. The curves illustrate an increasing risk for the two smoking outcomes dependent on the amount of tobacco ad contact, but not for non-tobacco advertising contact.

Figure 1.

Dotted line represents tobacco advertising; solid line represents non-tobacco advertising. Figures in brackets = 95% CI. IRR, Incidence Rate Ratio for 10 additional advertising contacts. n.s., not significant; *=p<0.05; ***=p<0.001.

The figures also report the adjusted incidence rate ratios associated with an increase in advertising exposure. There was an adjusted IRR for established smoking of 1.38 (95% CI 1.16 to 1.63; p<0.001) for each additional 10 tobacco ad contacts and 1.00 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.19; p=0.996) for each additional 10 non-tobacco ad contacts. For daily smoking, the corresponding IRRs were 1.30 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.64; p=0.029) for 10 tobacco ad contacts and 0.92 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.08; p=0.296) for 10 non-tobacco ad contacts, respectively.

Owing to the skewed distribution of tobacco ad contact frequency (more than half of the never-smoking students had fewer than 10 contacts), we repeated the analysis using contact frequency parsed into tertiles, representing relative low (0–2.5), medium (5–10) and high (11–55) advertising contact. For established smoking, the adjusted IRRs were 1.52 for tobacco ads (95% CI 1.14 to 2.03; p=0.004) and 1.05 for non-tobacco ads (95% CI 0.68 to 1.62; p=0.819). Using daily smoking as an outcome variable, the IRRs were 1.43 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.90; p=0.012) and 0.84 (95% CI 0.58 to 1.22; p=0.363) for each additional tertile of tobacco and non-tobacco advertising contact. These IRRs relate to a 3.1%, 4.8% and 7.3% established smoking attributable incidence rate or a 3.1%, 4.6% and 6.4% daily smoking incidence for low, medium and high tobacco advertising contact, respectively, assuming that the adjusted analysis adequately controlled for the third variable influence.

To address the question if some never-smokers had higher tobacco advertising contact because they were already more susceptible to smoking at baseline, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with only never-smokers with low susceptibility. These students reported at baseline that they would definitely never-smoke in the future and also would definitely not try cigarettes if a friend offered one (n=803). In this restricted subsample, the adjusted IRR for each additional 10 tobacco ad contacts was 1.37 for established smoking (95% CI 1.07 to 1.76; p=0.012) and 1.33 for daily smoking (95% CI 1.02 to 1.75; p=0.038). Again, no significant associations were found for non-tobacco advertisements.

Discussion

This longitudinal study is a further test of the relationship between tobacco advertising exposure and youth smoking behaviour, confirming the specificity of the advertising-smoking link by comparing the effects of tobacco versus non-tobacco advertising. The study extends previous work by using two less prevalent outcome measures (established and daily smoking) and a longer follow-up period of 2.5 years, measures likely to indicate an addiction component to the smoking.21 Compared with the results reported on smoking initiation in terms of ever smoking (even a few puffs),9 the increase in the adjusted relative risk for daily smoking dependent on tobacco advertising exposure was even more pronounced. Specificity was shown by the finding that tobacco advertising at baseline predicted these outcomes independent of the amount of general advertising contact and after controlling for a number of well-known risk factors for smoking initiation. This result confirms the content-specific association between tobacco advertising and smoking behaviour and underlines that tobacco advertising exposure is not simply a marker for adolescents who are generally more receptive or attentive to marketing. In addition, a subsample sensitivity analysis revealed that the association between tobacco advertising exposure and smoking uptake was also found in the group of unsusceptible never-smokers. This is important as one could argue that never-smokers with a higher exposure were already more susceptible to smoking at baseline and therefore more attentive to the tobacco ads.

This longitudinal study also clearly points out the implications of partial tobacco advertising bans in countries like the USA and Germany. One-third of the adolescents in the highest tertile of advertising had rates of daily and established smoking that were double (three percentage points higher) those of adolescents in the first tertile. By contrast, assuming that the models were fully adjusted for other confounding influences, one might expect a significant further decrease in youth smoking uptake in these countries after total elimination of tobacco advertising.

Some limitations of the study have to be considered. There was a severe loss of students during the 30 month interval (44%). To a large degree, the drop-out was related to organisational issues (eg, school and class changes) that are unlikely to be systematically related to advertising exposure or smoking behaviour on an individual level. However, the lost students differed on a couple of dimensions from the retained students, that is, age, gender, socioeconomic status, school performance, sensation seeking and parental smoking. With the exception of lower age, the drop-out markers indicate that lower risk adolescents were more likely to be retained. This might have biased the results as the effect of one risk factor might not be independent of other risk factors. Generally, one would assume that the associations become more conservative if higher risk adolescents are excluded, because this group has a higher likelihood of starting to smoke. However, in the context of media effects on smoking initiation, there is also evidence that lower risk adolescents have a higher responsiveness towards media effects,22 23 indicating that the present results might not be generalised to the whole population of adolescents. Second, as with any observational study, the results may be biased by unmeasured confounding—that is, an unmeasured risk factor could alter the estimates reported for the association between tobacco advertising and smoking onset. Third, the memory-based measure of ad exposure could be biased by memory effects other than the ones we controlled for. The potential to remember ads (in terms of contact frequency) should, however, not be completely independent of actual exposure. Finally, because the implemented method did not use a representative sample of all broadcasted ads, it does not allow for an accurate estimation of the total amount of tobacco and non-tobacco advertising exposure or the advertising pressure of specific brands. This is amplified by the modification of the stimulus material which did not contain any brand information.

The finding that exposure to tobacco advertising predicts smoking in youth could have important public health implications. A total ban of tobacco advertising and promotion around the world is one key policy measure of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).24 Under Article 13.1 of FCTC, ‘Parties recognise that a comprehensive ban on advertising, promotion and sponsorship would reduce the consumption of tobacco products’. Data from this study support this measure, because only exposure to tobacco advertisements predicted smoking initiation, which cannot be attributed to a general receptiveness to marketing, and because it shows that advertising allowed under partial bans is still reaching adolescents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mandy Gauditz, Lars Grabbe, Sven Heid, Frank Kirschneck, Carmen and Sarah Koynowski, Detlef Kraut, Corinna Liefeld, Karin Maruska, Danuta Meinhardt, Marc Räder, Jan Sänger and Gesa Sander for assessing the data.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the completion of the project. MM and RH performed the analysis and interpretation of data. MM and BI contributed to the collection and assembly of data. MM, JDS and RH helped in the drafting of the article. All authors conducted a critical revision of the article and granted final approval of the article for important intellectual content. All authors had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study implementation was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Kiel (Ref.: D 417/08).

Funding: This study was financed by DAK-Gesundheit, a German health insurance firm.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Kiel (Ref.: D 417/08).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Brandt AM. The cigarette century: the rise, fall and deadly persistence of the product that defined America. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollay RW. Targeting youth and concerned smokers: evidence from Canadian tobacco industry documents. Tob Control 2000;9:136–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(10):CD003439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henriksen L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob Control 2012;21:147–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strasburger VC. Policy statement—children, adolescents, substance abuse, and the media. Pediatrics 2010;126:791–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill AB. The environment and disease: association or causation?. Proc R Soc Med 1965;58:295–300 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanewinkel R, Isensee B, Sargent JD, et al. Cigarette advertising and adolescent smoking. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:359–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanewinkel R, Isensee B, Sargent JD, et al. Cigarette advertising and teen smoking initiation. Pediatrics 2011;127:e271–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kenford SL, Wetter DW, Welsch SK, et al. Progression of college-age cigarette samplers: what influences outcome. Addict Behav 2005;30:285–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galanti MR, Siliquini R, Cuomo L, et al. Testing anonymous link procedures for follow-up of adolescents in a school-based trial: the EU-DAP pilot study. Prev Med 2007;44:174–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klitzner M, Gruenewald PJ, Bamberger E. Cigarette advertising and adolescent experimentation with smoking. Br J Addict 1991;86:287–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum The Tobacco Atlas Germany 2009. Heidelberg: Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (in German), 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bondy SJ, Victor JC, Diemert LM. Origin and use of the 100 cigarette criterion in tobacco surveys. Tob Control 2009;18:317–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, et al. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol 1996;15:355–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Predicting young adults’ health risk behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;69:505–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychol Bull 1992;112:64–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychol Bull 1995;117:67–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunter M, Schümer G, Artelt C, et al. Pisa 2000: Documentation of measures. Berlin: Max-Planck-Institiut für Bildungsforschung (in German), 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russo MF, Stokes GS, Lahey BB, et al. A sensation seeking scale for children: further refinement and psychometric development. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 1993;15:69–85 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sargent JD, Mott LA, Stevens M. Predictors of smoking cessation in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998;152:388–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, et al. Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: a cohort study. Lancet 2003;362:281–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD. Exposure to smoking in internationally distributed American movies and youth smoking in Germany: a cross-cultural cohort study. Pediatrics 2008;121:e108–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibuya K, Ciecierski C, Guindon E, et al. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: development of an evidence based global public health treaty. BMJ 2003;327:154–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.