Abstract

Aim of the study

Erlotinib and gefitinib are reversible EGFR-TKI administered orally. Results of the phase III study JBR.21 proved the clinical efficacy of erlotinib-based regimens as second- or third-line treatment of advanced NSCLC. We analyze efficacy of treatment with erlotinib in patients suffering from advanced stage NSCLC who participated in the multicentre, international phase IV study – MO 18109 TRUST (expanded access clinical program of Tarceva™ in patients with advanced stage IIIB/IV NSCLC). Our analysis was performed based on clinical data derived from centres with the largest number of patients who received erlotinib.

Material and methods

Between May and November 2005, a total of 56 patients (19 women and 37 men) with histologic or cytologic diagnosis of NSCLC were included in the study. The histological diagnosis was: squamous-cell (n = 23), adenocarcinoma (n = 20), broncho-alveolar carcinoma (n = 2). In 11 patients the type of NSCLC was not specified.

Results

Patients received erlotinib in a single dose of 150 mg per day. Partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) were observed in 5 (9%), 33 (59%) and 16 (29%) patients respectively. Median PFS was 16.0 weeks. In the study population adverse events (AE) were noted in 12 (21%) patients.

Conclusions

Results of the TRUST study in the Polish population confirmed the efficacy of erlotinib in advanced NSCLC after failure of prior platinum-based chemotherapy. Treatment with erlotinib was associated with longer PFS as compared to the JBR.2 study, whole TRUST study population and Italian population included in the TRUST study.

Keywords: non-small cell lung cancer, erlotinib, TRUST, prognostic factors

Introduction

Each year, more than one million people die of lung cancer worldwide, whereas in Poland it is responsible for more than 20 000 deaths [1, 2]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for about 85% of all primary lung neoplasms. The majority of patients (approximately 80%) present with advanced disease and their prognosis is poor. However, if the management is tailored based on clinical characteristics, patients might derive some benefit from treatment in terms of survival and quality of life. The value of chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC was first confirmed in a meta-analysis published in 1995 [3]. Two-drug platinum-based regimens and novel chemotherapeutic-based regimens are recommended as the first-line chemotherapy, which usually consists of four cycles [4–9]. Selected patients with disease progression after a prior chemotherapy regimen may benefit from second-line treatment with docetaxel or pemetrexed, which is particularly justified in the subgroup with at least three-months long response to first-line chemotherapy [4, 10, 11]. Clinical efficacy of other cytotoxic agents or multidrug regimens as a second-line chemotherapy has not yet been proven [4, 12–15]. However, in case of cancer progression or contraindications to chemotherapy, the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) should be considered within second-line treatment. Furthermore, palliative radiotherapy or best supportive care only are also optional treatment methods of patients with advanced stage NSCLC.

Erlotinib and gefitinib are reversible EGFR-TKI administered orally [16]. Results of the phase III study BR.21 proved the clinical efficacy of erlotinib-based regimens as second- or third-line treatment of advanced NSCLC [17]. The trial showed significant survival prolongation compared to placebo in patients with disease progression after at least one chemotherapy line. In addition to prolongation of survival, patients who received erlotinib had longer median time to symptom deterioration (cough and dyspnoea) as well as improved quality of life. Treatment with erlotinib was well-tolerated – rash and diarrhoea were the most commonly observed adverse effects. The rate of response to erlotinib was higher among Asians, women, patients with adenocarcinoma, and lifetime non-smokers. However, the only significant independent predictors of beneficial effect on survival were Asian origin, a history of not smoking, presence of activating mutations in the EGFR gene, and a high number of EGFR copies [18].

The aim of this study was to analyse the efficacy of treatment with erlotinib in patients suffering from advanced stage NSCLC who participated in the multicentre, international phase IV study MO 18109 TRUST (expanded access clinical program of Tarceva™ in patients with advanced stage IIIB/IV NSCLC). Our analysis was performed based on clinical data derived from centres with the largest number of patients who received erlotinib.

Material and methods

Patients

Between May and November 2005, a total of 56 patients (19 women and 37 men) with histological or cytological diagnosis of NSCLC were included in the study. Most of them maintained very good or good performance status (ECOG 0-2). Disease stage at entry was IIIB or IV in 7 and 49 patients, respectively. The histological diagnosis was squamous-cell (n = 23), adenocarcinoma (n = 20), or broncho-alveolar carcinoma (n = 2). In 11 patients the type of NSCLC was not specified. Most patients (n = 46 – 82%) were active or lifetime smokers. The protocol of the MO 18109 study allowed the use of erlotinib as first-line therapy in case of contraindications to chemotherapy. However, erlotinib was administered only in one patient (2%) as a first-line treatment. The majority of patients received erlotinib as second- (n = 19 – 34%) or third-line (n = 36 – 64%) treatment. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the patients included in this analysis in comparison with the whole population of patients who participated in the TRUST study.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | TRUST – Poland | TRUST – Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number | % | number | % | ||

| No. of patients | 56 | 7039 | |||

| Age | median | 61 | 63 | ||

| minimum | 45 | 19 | |||

| maximum | 75 | 95 | |||

| Sex | female | 19 | 34 | 2795 | 40 |

| male | 37 | 66 | 4238 | 60 | |

| Race | white | 56 | 100 | 5136 | 73 |

| black | 0 | 0 | 29 | < 1 | |

| east Asian | 0 | 0 | 1348 | 19 | |

| other | 0 | 0 | 499 | 7 | |

| unknown | 0 | 0 | 27 | < 1 | |

| ECOG | 0 | 14 | 25 | 1572 | 22 |

| Performance status | 1 | 26 | 46 | 3662 | 52 |

| 2 | 12 | 21 | 1350 | 19 | |

| 3 | 4 | 7 | 438 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 17 | < 1 | |

| Disease stage at diagnosis | IIIB | 7 | 13 | 1540 | 22 |

| IV | 49 | 88 | 5422 | 77 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 15 | < 1 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 62 | < 1 | |

| Pathology | adenocarcinoma | 20 | 36 | 3867 | 55 |

| bronchoalveolar carcinoma | 2 | 4 | 390 | 6 | |

| large-cell carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 400 | 6 | |

| squamous-cell carcinoma | 23 | 41 | 1650 | 23 | |

| NSCLC unspecified | 11 | 20 | 708 | 10 | |

| unknown | 0 | 0 | 14 | < 1 | |

| Line of treatment | first line | 1 | 2 | 983 | 14 |

| second line | 19 | 34 | 3450 | 49 | |

| third line | 36 | 64 | 2538 | 36 | |

| other | 0 | 0 | 54 | < 1 | |

| unknown | 0 | 0 | 14 | < 1 | |

| Smoking status | never smoked | 10 | 18 | 2199 | 31 |

| active or lifetime smoker | 46 | 82 | 4805 | 68 | |

| unknown | 0 | 0 | 35 | < 1 | |

Patients younger than 18 years, with previous history of other cancer disease, pregnant women, and patients with metastases in the central nervous system or with psychiatric, psychological and social contraindications to chemotherapy were excluded from the study.

Haematological and biochemical parameters of all patients were within acceptable limits.

Treatment

Patients received erlotinib in a single dose of 150 mg per day. Treatment modifications (dose reduction from 100 mg to 50 mg daily) were performed in accordance with the study protocol. Erlotinib was continued until progression of disease or discontinued due to adverse effects or patient's request.

Trial methodology

The primary objective of this study was to determine the response rate, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) as well as to assess the safety and toxicity of treatment with erlotinib (presented analysis does not include OS).

Response to the study treatment was assessed at eight-week intervals according to RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors). The analysis of safety and toxicity of the study drug was performed every four weeks. Partial or complete responses had to be confirmed within 28 days after the first evaluation.

Statistical analysis was performed using the program SAS v.8.2.

Results

Response rate

None of the patients from our study group met the RECIST criteria for complete response (CR). Partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD) was observed in 5 (9%), 33 (59%) and 16 (29%) patients respectively. Evaluation of response was not performed in one patient (2%) as he was still receiving erlotinib at the end of the observation period. One patient was excluded from the analysis due to missing data, and one due to discontinuation of treatment. We performed renewed analysis of final response excluding the patient with missing data. Results were comparable with those from previous analysis: CR, PR, SD and PD were 0 (0%), 5 (9%), 33 (60%) and 16 (29%) respectively. The disease control rate (DCR), defined as the sum of CR, PR and SD, was 69% (38 out of 55 patients). Response rates are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Response rates to study treatment

| Response to treatment | n = 56 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response | 0 | 0 |

| Partial response | 5 | 9 |

| Stable disease | 33 | 59 |

| Progressive disease | 16 | 29 |

| Undetermined | 1 | 2 |

| No data | 1 | 2 |

Table 3.

Response rates to the study treatment excluding missing data

| Response to treatment | n = 55 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Complete response | 0 | 0 |

| Partial response | 5 | 9 |

| Stable disease | 33 | 60 |

| Progressive disease | 16 | 29 |

| Undetermined | 1 | 2 |

Duration of treatment

The majority of patients received treatment over a period of 8 to 16 weeks. Twenty patients (36%) were treated longer than 16 weeks. Distribution of treatment duration is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Duration of treatment

| Weeks | Number of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 4 | 3 | 5 |

| > 4-8 | 8 | 15 |

| > 8-16 | 24 | 44 |

| > 16-26 | 9 | 16 |

| > 26-52 | 8 | 15 |

| > 52-104 | 3 | 5 |

Median duration of treatment performed as a first-, second- or third-line therapy was respectively 8.0, 15.9 and 12.9 weeks. Data on duration of treatment depending on the line of treatment are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Duration of treatment according to the line of treatment (weeks)

| Weeks | Total | First line | Second line | Third line |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 55 | 1 | 19 | 35 |

| Minimum | 3.1 | 8.0 | 4.6 | 3.1 |

| Median | 13.1 | 8.0 | 15.9 | 12.9 |

| Maximum | 77.1 | 8.0 | 43.9 | 77.1 |

Progression-free survival

Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as time from the beginning of erlotinib administration to the first sign of PD according to the RECIST criteria or death. In 7 patients, who either still continued treatment with erlotinib or had no progression, PFS was determined on the basis of the latest examination date. The study group was analysed twice. The first analysis, based on 49 patients, included only individuals with confirmed PD. The second analysis also covered patients without well-documented PD, thus including 51 cases.

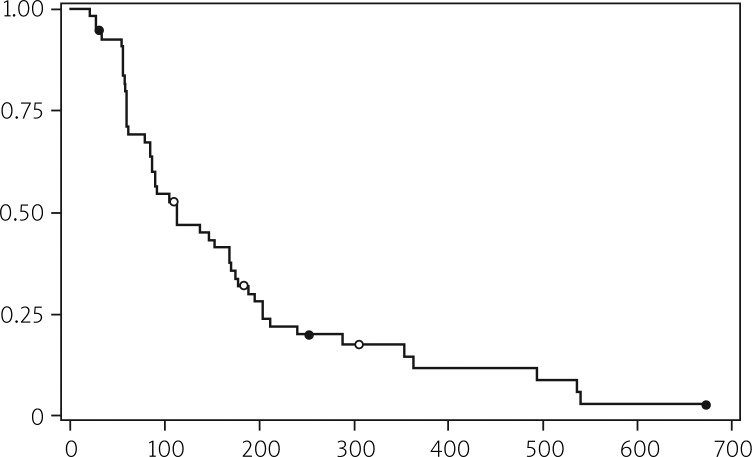

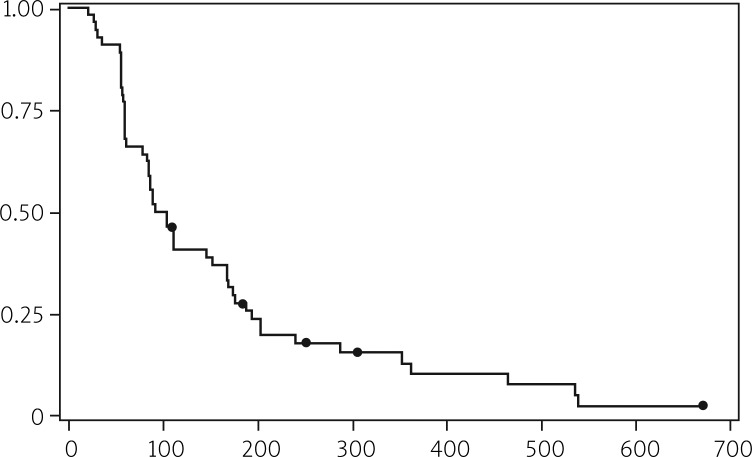

Median PFS in both analyses was 16.0 and 13.9 weeks, respectively. More detailed information is shown in Tables 6 and 7 and illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 6.

Progression-free survival according to the RECIST classification

| All patients | 56 | ||

| Patients with progressive disease | 49 | ||

| Patients without progressive disease (censored) | 7 | ||

| % censored | 12.50 | ||

| Progression-free survival | Days | Weeks | Months |

| Median | 112 | 16.0 | 3.68 |

| 95% confidence interval | 86-169 | 12.3-24.1 | 2.83-5.55 |

| Range | 21-673 | 3.0-96.1 | 0.69-22.11 |

Table 7.

Progression-free survival (progressive disease according to RECIST + clinical progression)

| All patients | 56 | ||

| Patients with progressive disease | 51 | ||

| Patients without progressive disease (censored) | 5 | ||

| % censored | 8.93 | ||

| Progression-free survival | Days | Weeks | Months |

| Median | 98 | 13.9 | 3.20 |

| 95% confidence interval | 83-152 | 11.9-21.7 | 2.73-4.99 |

| Range | 21-673 | 3.0-96.1 | 0.69-22.11 |

Fig. 1.

Progression-free survival (objective progression)

Fig. 2.

Progression free survival (objective and undocumented)

Adverse events

Safety and toxicity of treatment were analysed according to System Organ Class of MedDRA version 10 and Common Toxicity Criteria-Adverse Events (CTC-AE) version 3.0. In the study population adverse events (AE) were noted in 12 (21%) patients. Grade 1-5 of AE intensity was noted in 1 (2%), 1 (2%), 3 (5%), 3 (5%) and 4 (7%) cases, respectively. In 11 patients (20%) serious adverse events (SAE) were diagnosed. None of the SAE, discontinuations or deaths were associated with erlotinib. Frequency and severity of AE and SAE are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8.

Frequency and severity of adverse events and serious adverse events

| Number | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with at least one adverse events | 12 | 21 | |

| Adverse events grade | grade 1 | 1 | 2 |

| grade 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| grade 3 | 3 | 5 | |

| grade 4 | 3 | 5 | |

| grade 5 | 4 | 7 | |

| Patients with at least one serious adverse events | 11 | 20 | |

| Patients with at least one serious adverse events induced by treatment | 0 | 0 | |

| Patients who discontinued treatment due to serious adverse events | 0 | 0 | |

| Deaths during the treatment or 30 days after the end of the study | 6 | 11 | |

| Deaths linked to adverse events induced by the treatment | 0 | 0 | |

The most common adverse effect (68%, n = 38) was rash reported during treatment. Rash of grade 1 or 2 was observed in 33 (59%) cases whereas grade 3 or 4 was noted in only 5 (9%) patients. Seven (13%) patients required dose reductions due to drug-related toxicity. Distribution of necessary erlotinib dose reductions is shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Reduction of erlotinib doses

| Number | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients who received dose modification | 7 | 13 |

| Reduction to 100 mg | 7 | 13 |

| Reduction to 50 mg | 1 | 2 |

| Other reductions | 1 | 2 |

The most frequent reasons for erlotinib dose reduction were rash (n = 4 – 7%), diarrhoea (n = 2 – 3.6%) and conjunctivitis (n = 1 – 1.8%).

Haematological or biochemical abnormalities during erlotinib treatment were not clinically significant. Table 10 shows frequencies of abnormal findings in laboratory examination noted in particular weeks of treatment.

The most common reason for treatment interruption was PD, which was noted in 44 (80%) individuals. Other causes were deterioration of performance status in 5 (9%) patients and patient's request to discontinue treatment in 6 (11%).

Discussion

Expression of EGFR, which has been noted in the majority of patients with NSCLC, justifies the use of anti-EGFR drugs, such as monoclonal antibodies or TKI-EGFR [16]. Erlotinib and gefitinib bind to the intracellular domain of EGFR TK, blocking signal transduction and tumourigenic effects associated with EGFR activation [4]. However, phase III studies did not prove that adding gefitinib or erlotinib to standard chemotherapy improves rates of survival in patients with advanced stage NSCLC [19–22]. In spite of promising results of IDEAL-1 and IDEAL-2 clinical trials, the efficacy of gefitinib in monotherapy after failure of the first-line platinum-based regimen has not been definitely confirmed [25]. There was also no difference in response rates and survival rates between patients treated with gefitinib in comparison with those treated with docetaxel in second-or third-line chemotherapy after the failure of the first-line platinum-based regimen [26, 27].

Erlotinib is currently the only one epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for use as the subsequent line of chemotherapy after failure of the first and other line platinum-based regimen. In one phase III study, treatment with erlotinib resulted in statistically longer survival as compared with placebo – median OS 6.7 vs. 4.7 months (p < 0.001), median PFS 2.2 vs. 1.8 months (p < 0.001), 1-year survival rate 31% vs. 21% – while response rate was 8.9% as compared to less than 1% (p < 0.001) [17]. Significantly more patients in the erlotinib group had a clinically significant improvement in quality of life, assessed by prolongation of median time to symptomatic deterioration (dyspnoea – 4.7 vs. 2.9 months, cough – 4.9 vs. 3.7 months, and pain – 2.8 vs. 1.9 months) [17, 28].

Detailed comparison between characteristics of the present study group and the whole TRUST population revealed some differences. First of all, our study population consisted only of white Caucasians, whereas 20% of the TRUST study population were patients of Asian origin. The higher percentage of Asians in the whole TRUST study may have contributed to the better response to treatment. Secondly, the distribution of histological features of tumours in the studies differed – we noted twice as many squamous-cell carcinomas as in the total TRUST population (41% vs. 23%), while adenocarcinoma were more rarely observed in our study group (36% vs. 55%). There was also a marked difference in the smoking status of patients. Lifetime smokers constituted 18% of our study population and 31% in the total TRUST study group. Finally, erlotinib was administered as a different line of treatment in these two studies. Only 2% of patients from our analysis received erlotinib as a first-line treatment in comparison with 14% in the total TRUST study population. Erlotinib was administered in our patients as a second and third line of chemotherapy in 34% and 64% cases in comparison with 49% and 36% in the total TRUST population. In our analysis the majority of patients were given erlotinib as a third-line treatment (64%). No significant differences in age or sex, performance status or stage of disease were noted between the two studies.

Analysis of our study results compared to the BR.21 study results revealed the same differences as were observed when comparing our study patients with the total TRUST study population [17, 29, 30]. Objective response rates (CR + PR) were similar to those in BR.21 (9.0 vs. 8.9%) [17]. There was no difference in DCR (CR + PR + SD) between our study population and the total TRUST study population (69% vs. 69%) [30]. Median progression-free survival in our study was longer not only in comparison with BR.21 (16.0 vs. 9.7 weeks), but also with respect to PFS observed in the total TRUST study population (16.0 vs. 14.1 weeks) and in the Italian TRUST study population (16.0 vs. 15.0 weeks). Because of the fact that more patients in the BR.21 and TRUST studies were non-smoking East Asians with adenocarcinoma (factors known to be predictive for benefit from erlotinib) the difference in median OS and PFS is somewhat surprising [4, 30].

There was a similar rate of toxicity induced by erlotinib in our study population in comparison with the total TRUST study population. The most common adverse event (68%) was a rash reported during treatment (BR.21 – 75%, TRUST – 70%) [17, 30]. There was no difference between the population of our study and BR.21 in frequency of rash of grades 3 and 4 [17]. In both studies the most frequent reasons for erlotinib dose reduction were rash and diarrhoea [17]. None of the SAE were associated with erlotinib or contributed to discontinuation of chemotherapy, whereas in the TRUST, Italian TRUST and BR.21 studies SAE constituted 5%, 4% and 5% respectively [17, 30, 31]. Moreover, in our analysis the frequency of adverse events was lower (21%) than that found in the TRUST (52%) and Italian TRUST (35%) population [30, 31]. However, inclusion of patients in these three analysed studies was based neither on EGFR expression nor EGFR gene amplification and mutation, which are predictive factors of efficacy for TKI-EGFR. The positive predictive value of EGFR expression [32] as well as EGFR amplification and mutation must be confirmed in prospective trials [18, 33–35].

In conclusion: results of the TRUST study in the Polish population confirmed the efficacy of erlotinib in advanced NSCLC after failure of prior platinum-based chemotherapy. Treatment with erlotinib was associated with longer PFS as compared to the BR.21 study, the whole TRUST study population and the Italian population included in the TRUST study. Response rates were nearly identical to those noted in the BR.21 and TRUST studies. Erlotinib was well tolerated, with rash being the most frequently noted adverse event.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Murray T, Ward E, Samuels A, Tiwari RC, Ghafoor A, Feuer EJ, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2005. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:10–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rachtan J, Sokolowski A, Niepsuj S, Zemla B, Zwierko M. Familial lung cancer risk among women in Poland. Lung Cancer. 2009;65:138–43. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. BMJ. 1995;311:899–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Socinski MA, Morris DE, Masters GA, Lilenbaum R. American College of Chest Physicians. Chemotherapeutic management of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2003;123:226S–43S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.226s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baggstrom MQ, Stinchcombe TE, Fried DB, Poole C, Hensing TA, Socinski MA. Third-generation chemotherapy agents in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:845–53. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31814617a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delbaldo C, Michiels S, Syz N, Soria JC, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP. Benefits of adding a drug to a single agent or a 2-agent chemotherapy regimen in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:470–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotta K, Matsuo K, Ueoka H, Kiura K, Tabata M, Tanimoto M. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing Cisplatin to Carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3852–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ardizzoni A, Boni L, Tiseo M, et al. Cisplatin versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:847–57. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkelstein DM, Ettinger DS, Ruckdeschel JC. Long-term survivors in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: a Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:702–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.5.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2095–103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krzakowski M. Leczenie drugiej linii w niedrobnokomórkowym raku płuca. Onkol Prakt Klin. 2009;5:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeda K, Negoro S, Tamura T, et al. Phase III trial of docetaxel plus gemcitabine versus docetaxel in second-line treatment for non-small cell lung cancer: results of a Japan Clinical Oncology Group trial (JCOG0104) Ann Oncol. 2009;20:835–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krzakowski M, Douillard JY, Ramlau R, et al. Phase III study of vinflunine versus docetaxel in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with a platinium containing regimen. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(Suppl. 18):387. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramlau R, Gervais R, Krzakowski M, et al. Phase III study comparing topotecan to intravenous docetaxel in patients with pretreated advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2800–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciardiello F, De Vita F, Orditura M, Tortora G. The role of EGFR inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2004;16:130–5. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200403000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer – molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:133–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III trial – INTACT 1. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:777–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, Schiller JH, et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III trial – INTACT 2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:785–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatzemeier U, Pluzanska A, Szczesna A, et al. Phase III study of erlotinib in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the Tarceva Lung Cancer Investigation Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1545–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R, et al. TRIBUTE: a phase III trial of erlotinib hydrochloride (OSI-774) combined with carboplatin in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5892–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (the IDEAL Trial) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2237–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2149–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niho S, Ichionese Y, Tamura T. Results of a randomized phase III study to compare the overall survival of gefitinib (IRESSA) versus docetaxel in Japanese patients with non-small cell lung cancer who failed one or two chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18S):LBA 7509. ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings, Part I. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Douillard JY, Kim ES, Hirsh V, et al. Phase III, randomized, open-label, parallel-group study of oral gefitinib (IRESSA) versus intravenous docetaxel in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer who have previously received platinum-based chemotherapy (INTREST) Eur J Cancer Supplements. 2007;6:2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bezjak A, Tu D, Seymour L, et al. Symptom improvement in lung cancer patients treated with erlotinib: quality of life analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trial Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3831–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ardizzoni A, Evangelia R, Mikhail L, et al. Interim safety results from TRUST, a global open-label study of erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(Suppl. 4):S342. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groen H, Arrieta OG, Riska H, et al. The global TRUST study of erlotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1900. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tiseo M, Gridelli C, Cascinu S, et al. An expanded access program of erlotinib (Tarceva) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): data from Italy. Lung Cancer. 2009;64:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark GM, Zborowski DM, Culbertson JL, et al. Clinical utility of epidermal growth factor receptor expression for selecting patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer for treatment with erlotinib. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:837–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sequist LV, Bell DW, Lynch TJ, Haber DA. Molecular predictors of response to epidermal factor receptor antagonists in non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:587–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gridelli C, Ardizzoni A, Ciardiello F, et al. Second-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:430–40. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318168c815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]