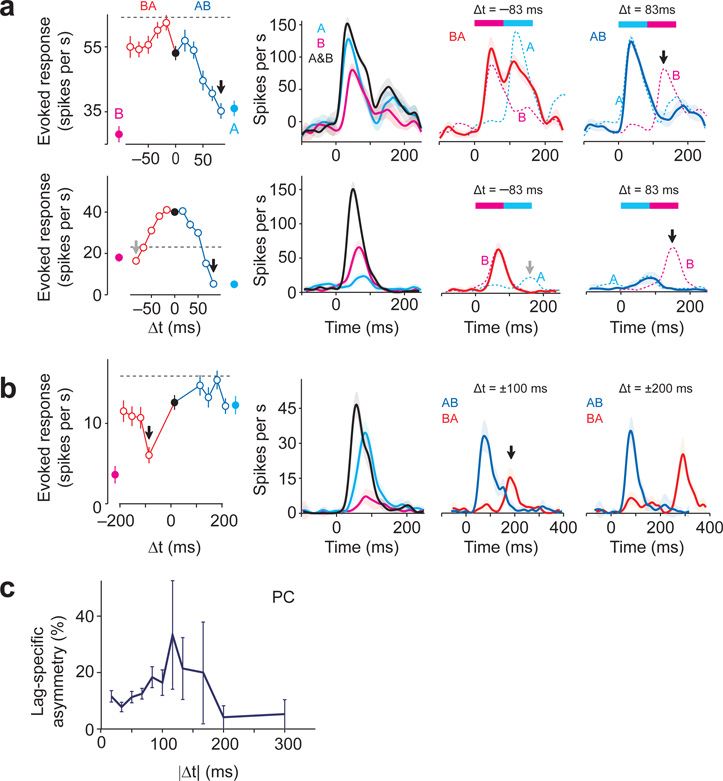

Figure 5. Delayed inhibition shapes the responsivity of PCNs.

(a) Upper panel, TTC of an example pPC neuron. The same neurons as in Fig. 2d, h. Second panel, PETHs of the responses. The response decreased steeply with increasing Δt for A→B but not for B→A. Middle panel, Δt = −83 ms; right panel, Δt = 83 ms. Dashed lines in the right two panels represent expected firing rate changes in response to the corresponding spot (A or B). The second stimulation was effective in evoking responses with Δt = 83 ms (third panel), but not with Δt = −83 ms (fourth panel, black arrow). Lower panel, TTC of a pPC neuron. With Δt = ±83 ms, the response to A→B differed significantly from that of B→A (left panel, black and gray arrows). Note that second spot stimulation did not elicit the expected responses in both orders (third and fourth panels, black and gray arrows).

(b) TTC of a pPC neuron which was tested with longer lags (Δt = 100, 133, 167 and 200 ms). The TTC is asymmetric at Δt = ±100 ms (black arrow, P = 0.000023, t78 = 4.5, t-test, n = 40 repetitions) but similar for Δt = 200 ms (P = 0.72, t-test, t78 = 0.36). With Δt = −100 ms, stimulation of the second spot A does not elicit a strong response (third panel, B→A, red line and black arrow). However, with a larger lag (Δt = ±200 ms), the response to spot A resumed (red line in the fourth panel).

(c) Percentages of lag-specific asymmetry in TTCs for each lag for all PCNs. Mean ± s.e.m. based on the binomial model.