Introduction

Epigenetic inheritance refers to the transmission of modified genetic material from one generation to the next. These “epialleles” are not caused by mutations in the DNA sequence, but instead by covalent modification of chromatin and DNA, guided by developmental and environmental cues. In general, epigenetic modifications that are programmed during development must be reset in the germline, so that the zygote is restored to pluripotency and can once again initiate embryonic development. For example, imprinted genes in the mouse are expressed predominantly from either the paternal allele or from the maternal allele in the diploid embryo, and so must be reprogrammed in the germline depending on its sex (Bartolomei and Ferguson-Smith, 2011). Indeed, the mouse genome undergoes several rounds of DNA methylation, demethylation and repair as germ cells differentiate, as well as in the embryo after fertilization when imprinted genes are largely immune (Bartolomei and Ferguson-Smith, 2011; Feng et al., 2010; Popp et al., 2010). For this reason, epigenetic inheritance is thought to be rare in mammals, and is generally restricted to non-essential genes.

Flowering plants are an important exception to this rule, as epigenetic modification during development can be inherited for hundreds of generations with dramatic developmental consequences (Cubas et al., 1999). The first (and most common) examples of epigenetic inheritance in plants involved transposable elements (TE), which can regulate nearby genes, and undergo epigenetic switches during development, resulting in the inheritance of epialleles (Martienssen et al., 1990; McClintock, 1965). As in mammals, epigenetic inheritance of transposon activity in plants involves DNA methylation (Becker et al., 2011; Cubas et al., 1999; Martienssen and Baron, 1994; Schmitz et al., 2011). Imprinted genes tend to be flanked by transposable elements, whose methylation can influence their expression (Radford et al., 2011). However, imprinting in plants is largely restricted to the extra-embryonic endosperm, a terminally differentiated tissue within the seed, so that imprinted chromatin and DNA modifications need not be removed once they are established (Feng et al., 2010; Jullien and Berger, 2009; Raissig et al., 2011). The extent of reprogramming in the plant germline thus remains an important question.

Unlike mammals, which set aside their germline in early development, flowering plants give rise to germ cells during post-embryonic growth and development, in some cases many years after embryogenesis is complete. The pollen mother cell (PMC) on the paternal side and the megaspore mother cell (MMC) on the maternal side are specified from somatic cells in developing flowers (Boavida et al., 2005). In the anthers, the PMC undergoes meiosis resulting in four haploid microspores. Each microspore subsequently undergoes an asymmetric division to differentiate a larger vegetative cell and a smaller generative cell, which represents the male germline (Figure 1A). The vegetative cell exits the cell cycle into G0, while the generative cell undergoes a further symmetric division to produce two identical sperm cells that are surrounded by the vegetative cell (Berger and Twell, 2011).

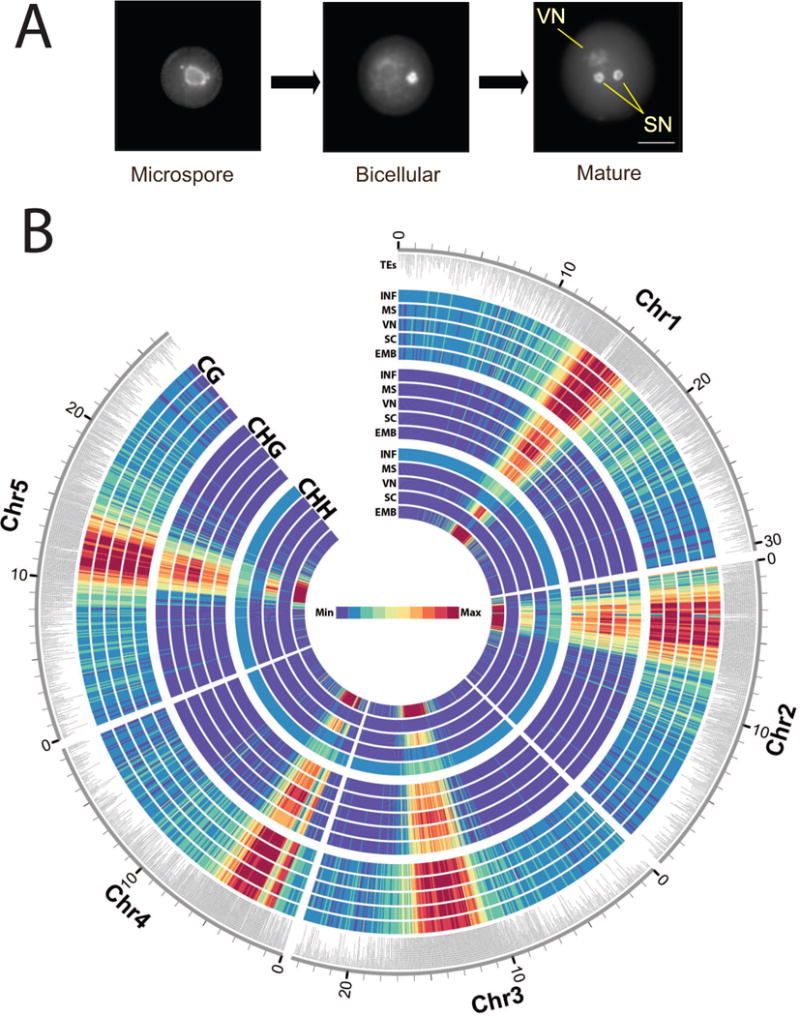

Figure 1. DNA methylation and small RNA accumulation during pollen development.

(A) Pollen development: the uninucleate microspore divides asymmetrically giving rise to bicellular pollen, which consists of a larger vegetative cell embedding a smaller generative cell. A second mitotic division of the generative cell originates two sperm cells. The three cell types analyzed in this study were stained with DAPI to highlight heterochromatin, which is lost in the vegetative nucleus (VN) but not in the sperm cell nuclei (SC) (bar = 10μm). (B) Heat map representation of DNA methylation. Bisulfite sequencing of genomic DNA from each cell type was performed as described. Methylation density is represented in 10kb blocks, separated by context and cell type. CG (CG methylation), CHG (CHG methylation), CHH (CHH methylation), INF (Inflorescence), MS (Microspore), VN (Vegetative nucleus), SC (Sperm Cell), EMB (Embryo). The maximum value of the heat map is calibrated to the VN. The outer annotation track highlights the position of transposons (TEs).

The most conspicuous evidence of reprogramming in the plant germline is that the vegetative nucleus (VN) of the pollen grain has completely decondensed heterochromatin, in contrast to the tightly condensed chromatin found in sperm cell (SC) nuclei (Figure 1A). Heterochromatin in plants is mostly occupied by TEs and repeats (Lippman et al., 2004). TE repression is important for genome integrity and mutants in DDM1 (DECREASE in DNA METHYLATION 1) and MET1 (DNA METHYLTRANSFERASE 1) have reduced DNA methylation levels resulting in up regulation of TEs (Lippman et al., 2004). MET1 maintains CG methylation, and its activity in the germline impacts epigenetic inheritance (Jullien et al., 2006; Saze et al., 2003). In plants, CHROMOMETHYLASE3 (CMT3) maintains CHG methylation, guided by histone modification, and cytosines can also be methylated in an asymmetric CHH context guided by RNA interference (RNAi) (Law and Jacobsen, 2010). RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) requires the DNA methyltransferase DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLASE 2 (DRM2), and the RNA polymerase IV and V subunits NRPD1a, and NRPE1a, which are involved in production and utilization of 24nt siRNA (Haag and Pikaard, 2011). These mechanisms interact, so that RdDM is required to remethylate TEs in ddm1 mutants. TEs without matching siRNA cannot be remethylated even when DDM1 function is restored through crosses to wild-type plants (Teixeira et al., 2009).

Loss of heterochromatin in the vegetative nucleus of the pollen grain is accompanied by the loss of DDM1, the activation of TEs, and the production of a novel class of 21nt siRNAs which accumulate in sperm cells (Slotkin et al., 2009). However, while some TEs and repeats were found to be demethylated in the VN, others were hypermethylated so that the role of DNA methylation in pollen reprogramming was unclear (Schoft et al., 2011; Schoft et al., 2009; Slotkin et al., 2009). We set out to determine the dynamics of DNA methylation during pollen development, via bisulfite sequencing of genomic DNA from Arabidopsis microspores, and from their derivative sperm and vegetative cells (Figure 1A). We found that symmetric CG and CHG methylation were largely retained in Arabidopsis pollen. However, CHH methylation was lost from at least 1500 TEs, mostly long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons, in microspores and sperm cells. In the VN, more than 100 DNA transposons and non-LTR retrotransposons were targeted for CG demethylation by DNA glycosylases. Many of these transposons, including those that flank imprinted genes, gave rise to 24nt siRNA in sperm cells where DNA glycosylases are not expressed. Recently discovered recurrent epialleles were pre-methylated in sperm cells guided by a similar mechanism. Thus reprogramming of DNA methylation in pollen contributes to transposon silencing, the transgenerational recurrence of epialleles, and imprinting of maternally expressed genes.

Results

Sequencing of the methylome from individual pollen cell types presents a significant challenge, especially in Arabidopsis where pollen yields are limiting. Sperm cells and vegetative nuclei were isolated using Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS), through the use of cell specific promoters driving the expression of Red and Green Fluorescent Protein (RFP and GFP) (Borges et al., 2012). Microspores were obtained from young flower buds through a combination of mechanical filtration and purification through FACS, taking advantage of their small size and autofluorescent properties (Borges et al., 2012). Genomic DNA was isolated from each nuclear fraction, treated with sodium bisulfite and sequenced at 7–17x coverage (Table S1). To test whether each cytosine was methylated, the proportion of methylated reads to unmethylated reads was compared to the background error rate using a binomial test for each cytosine with sufficient coverage. The data was plotted as a heatmap on all five chromosomes, compared with the methylome of somatic cells from leaves (Figure 1B).

We observed a strong enrichment of DNA methylation in the pericentromeric heterochromatin in pollen (Figure 1B) resembling methylation profiles obtained previously from somatic cells (Cokus et al., 2008). The observed maintenance of symmetric CG and CHG methylation in pollen is consistent with expression of the maintenance DNA methyltransferases MET1 and CMT3 during microspore and generative cell division (Honys and Twell, 2004). Strikingly, however, CHH methylation in microspores and sperm cells was lost from pericentromeric retrotransposons and satellite repeats, and subsequently restored in the VN (Figure 1B).

Differential methylation of transposons in pollen cell types

To identify regions of the genome subject to differential methylation, we first identified Single Methylation Polymorphisms (SMPs) in a pairwise fashion (VN vs. microspore, SC vs. microspore, and VN vs. SC). Using the SMP information we next identified differentially methylated regions (DMRs). For CHH methylation, DMRs were defined as regions containing at least five SMPs, each < 50bp apart and containing a minimum of ten methylated cytosines. For CG and CHG methylation (which were far less variable), DMRs were defined as regions containing at least three SMPs, each < 50bp apart and containing at least five methylated cytosines. For each putative DMR the methylation calls were pooled across the whole region and then tested using Fisher’s exact test.

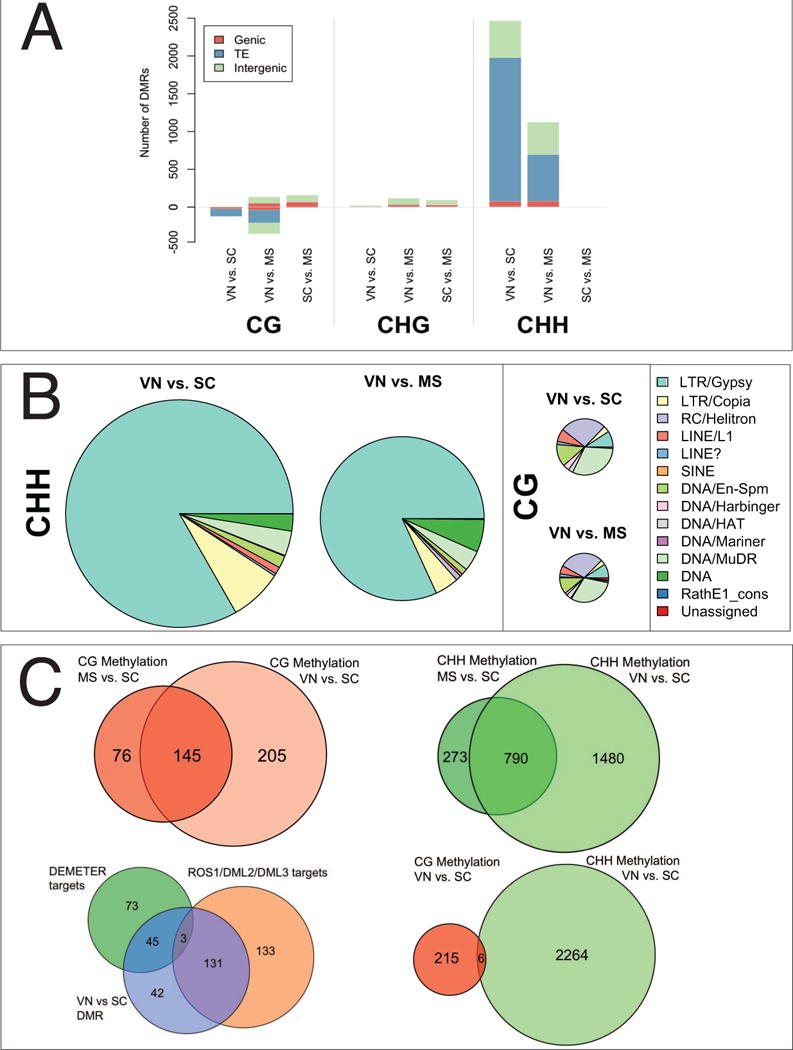

We found that almost all DMRs corresponded to intergenic regions and transposable elements, and strikingly, that almost all CHH DMRs were hypomethylated in sperm cells while CG DMRs were hypomethylated in the VN (Figure 2A). We found that 2270 CHH DMRs overlapped with 1781 different TEs, including 1483 LTR/Gypsy elements and 139 DNA transposons (Figure 2B, Table S2). Pairwise comparisons of VN vs. microspore and VN vs. SC yielded similar results (Figure 2A, B; Table S2) indicating that these retrotransposons were similarly unmethylated in microspores. An example of an Athila LTR retrotransposon, in which CHH methylation is reduced in microspores and sperm cells, is shown in Figure S1.

Figure 2. Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs) during pollen development.

(A) DMRs were detected in a pairwise manner by comparing the bisulfite-sequence profiles from each of the three pollen cell types (vegetative nucleus-VN, sperm cell-SC, and microspore-MS) in each methylation context (CG, CHG, CHH). Annotated features (Genic, TE and Intergenic) overlapping one or more DMR in each cell type and methylation context were identified using TAIR10 annotation. Bars represent the number of DMRs overlapping each feature class. Where a DMR overlaps two or more features each feature is counted once. (B) Scaled distribution of transposon classes overlapping DMRs in the VN. TEs that matched each DMR were identified. Where a DMR overlaps two or more TE superfamilies each overlap is counted once. DMRs that lost CG methylation in the VN were enriched for class II DNA transposons, while DMRs that lost CHH methylation in sperm cells were enriched for class I LTR/gypsy transposons. There were very few CHG DMRs (data not shown) and these did not overlap transposons. (C) CG DMRs (red, upper left) and CHH DMRs (green, upper right) were similar in pairwise comparisons between the VN and the microspore, and the VN and the SC. CG DMRs in the VN (blue, bottom left) overlap with DMRs detected between WT endosperm and dme endosperm (green, bottom left), which are targets of DEMETER (Hsieh et al., 2009), and with DMRs between inflorescence and ros1/dml2/dml3 inflorescence (Lister et al., 2008) which are targets of ROS1 and its homologs (orange, bottom left). In the VN, CG DMRs (pink, bottom right) and CHH DMRs (green, bottom right) do not overlap.

We uncovered 221 CG hypomethylated regions (CG DMRs) in the VN relative to the SC (Figure 2, Table S2) that overlapped with 109 different TEs (Table S2), including AtMu1a (At4g08680), as previously reported (Schoft et al., 2011; Slotkin et al., 2009). 29 of these TEs were RC/helitrons, 34 were DNA/MuDR transposons, and the remainders were mostly non-LTR retrotransposons (Figure 2B). A similar trend was observed in a pairwise comparison between VN and microspores (Figure 2A, B) and there was a high degree of overlap between CG DMRs in the VN in both pairwise comparisons (Figure 2C). In contrast, CG methylation was very similar in SC and microspores with only a very few loci demethylated in microspores (Figure 2A). These same loci (15/21 DMR) were also demethylated in the CHG context in microspores relative to VN and SC (Figure 2A). CG DMRs in the VN and CHH DMRs in SC did not overlap (Figure 2C), suggesting that differential methylation might be due to differential expression of DNA methyltransferases and DNA demethylases in each pollen cell type.

Loss of symmetric CG methylation in vegetative cells

The DNA glycosylase DEMETER (DME) is expressed in the VN, along with its homologs ROS1, DEMETER-LIKE2 (DML2) and DML3 (Schoft et al., 2011). DME is required for the demethylation of transposons and repeats that surround the imprinted Maternally Expressed Genes (MEGs) MEDEA (MEA) and FLOWERING OF WAGENINGEN (FWA). These genes are normally expressed from the maternal allele in the endosperm, but are also expressed in the VN of the pollen grain (Schoft et al., 2011). In order to determine whether CG DMRs in the VN were targets of DNA glycosylases, we performed pairwise analysis of CG DMRs between VN and SC, between endosperm and dme mutant endosperm (Hsieh et al., 2009), and between WT inflorescence and ros1/dml2/dml3 mutant inflorescence (Lister et al., 2008). Using the same DMR analytical pipeline, we found 267 targets of ROS1/DML2/DML3 (RDD) in inflorescence, and 121 targets of DME in the endosperm (Hsieh et al., 2009; Lister et al., 2008). Of the 221 DMRs hypomethylated in the VN, 134 DMRs were targets of RDD, and 48 were targeted by DME (Figure 2C). This accounts for 83% of all the DMRs which show decreased CG methylation in the VN compared to SC (Figure 2C). Similar values were obtained for CG DMRs between VN and microspore (Figure S2A). DME is only expressed in the VN of pollen and in the central cell of the female gametophyte, while ROS1, DML2 and DML3 are widely expressed in somatic tissues as well as in the VN. However, none of these genes are expressed in sperm cells (Schoft et al., 2011). Hence, DNA demethylases are responsible for the loss of CG in the VN.

Loss of asymmetric CHH methylation in sperm cells

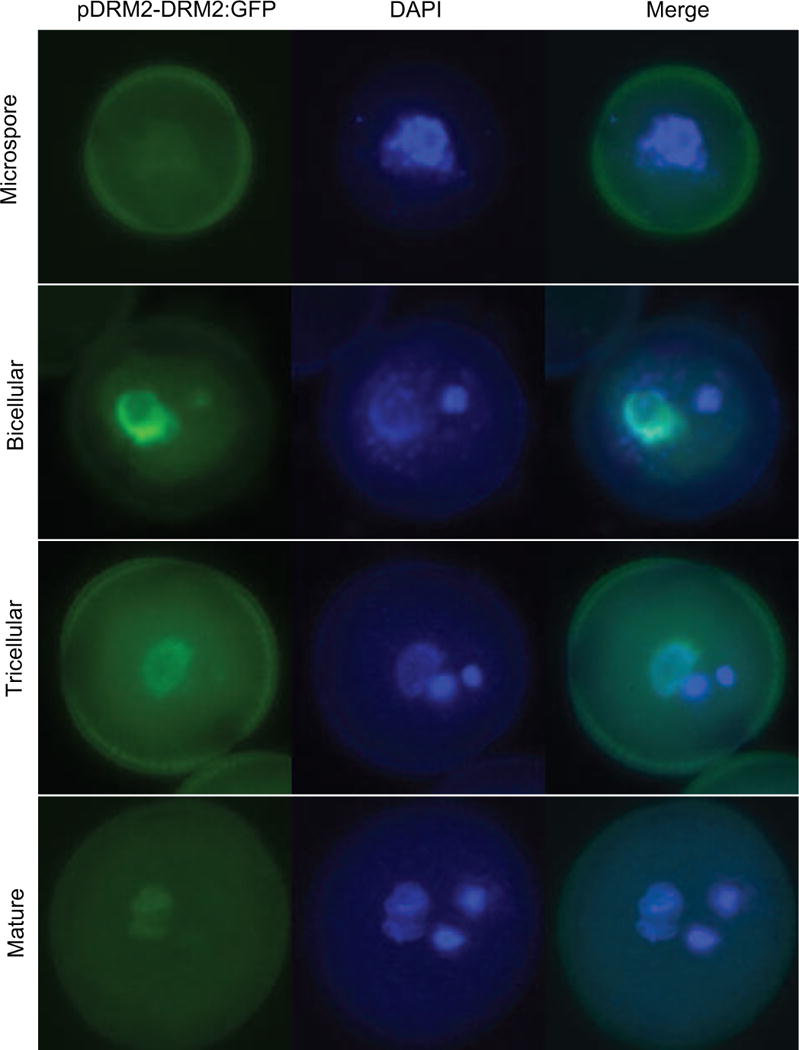

The overall level of CHH methylation in microspores was approximately half the level found in the inflorescence (Table S1), as if reductional division during meiosis was not accompanied by RNA directed DNA methylation (RdDM). CHH methylation in sperm cells was further reduced, and the remnants were observed on both DNA strands (Table S1), likely reflecting random segregation of unmethylated strands after meiosis (Schoft et al., 2009). We hypothesized that loss of CHH methylation in the SC could be the result of differential expression of proteins required for CHH methylation. The DNA methyltransferase DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE2 (DRM2), a homolog of mammalian Dnmt3, is required for CHH methylation, guided by 24nt siRNA (Cao and Jacobsen, 2002). We constructed a DRM2-GFP transgene fusion driven by the DRM2 promoter that was introduced into plants. We found that the DRM2-GFP fusion protein was barely detectable in microspores, but accumulated prominently in the VN at the bicellular stage (Figure 3). Very low levels were detected in the generative cell and in mature sperm cells (Figure 3), implying that the male germline has only a limited capacity for de novo CHH methylation which would account for progressive loss of CHH methylation from microspores to sperm cells.

Figure 3. DRM2 expression during pollen development.

GFP expression (green) was visualized in pollen from a pDRM2-DRM2::GFP transgenic plant, counterstained with DAPI (blue). Microspores and pollen at the bicellular, tricellular and mature stages are shown. DRM2 was expressed at a low level in the microspore and sperm cells, and at a much higher level in the vegetative nucleus at the bicellular and tricellular stage.

Small RNA guide remethylation of transposons and imprinted genes

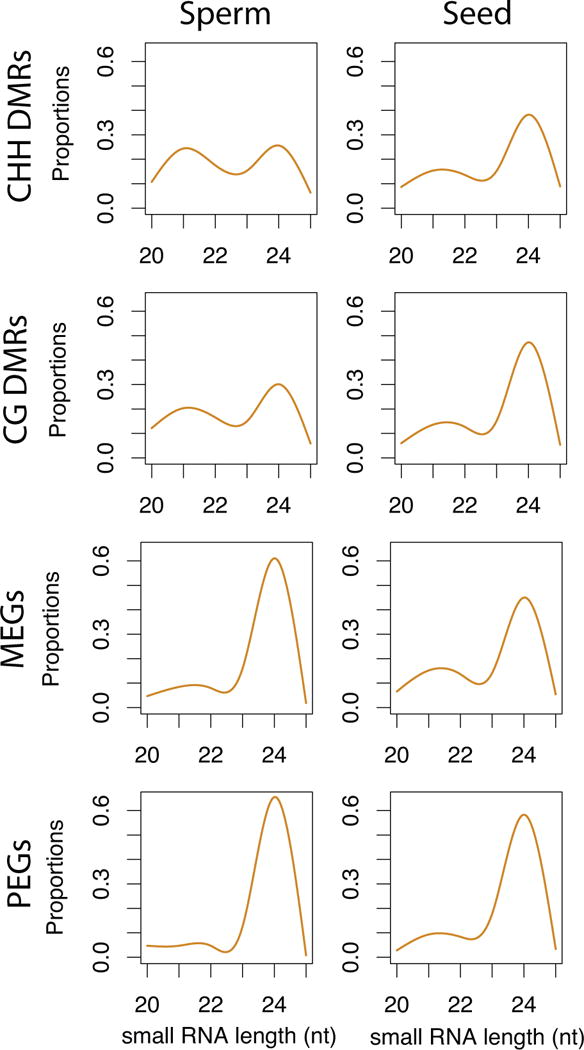

CHH methylation of retrotransposons is guided by 24nt small RNA (Haag and Pikaard, 2011; Law and Jacobsen, 2010). In sperm cells, CHH methylation is sharply reduced (Table S1; Figure 1B) and several genes required for 24nt siRNA biogenesis are no longer expressed in mature pollen (Grant-Downton et al., 2009; Honys and Twell, 2004; Pina et al., 2005) or sperm (Borges et al., 2008). CHH methylation is restored in the embryo (Hsieh et al., 2009; Jullien and Berger, 2012), and therefore must occur during or after fertilization. 24nt siRNA accumulate to high levels in the seed, and are maternal in origin in the seed coat and the endosperm (Lu et al., 2012; Mosher et al., 2009). Therefore, maternal 24nt siRNA might guide restoration of CHH methylation to incoming retrotransposons from sperm. To test this idea, we examined the size distribution of small RNA in sperm cells (Slotkin et al., 2009) and in seeds (Lu et al., 2012) corresponding to CHH DMRs in pollen (Figure 4). We found that DMRs that had lost CHH methylation in sperm cells matched both 21nt and 24nt siRNA in sperm cells but matched mostly 24nt siRNA in seeds (Figure 4). Thus retrotransposons that lost CHH methylation in sperm cells would be remethylated in seeds, guided at least in part by maternal 24nt siRNA, and high levels of RdDM activity during embryogenesis (Jullien and Berger, 2012).

Figure 4. Small RNA from Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs).

Small RNA in sperm cells (Slotkin et al., 2009) and seeds (Lu et al., 2012) were mapped to DMRs and plotted according to size. CHH DMRs were hypomethylated in sperm cells, while CG DMRs were hypermethylated. CG DMRs flanking Maternally and Paternally Expressed imprinted Genes (MEGs and PEGs) were also analyzed separately. Relative abundance of size classes is shown as proportions.

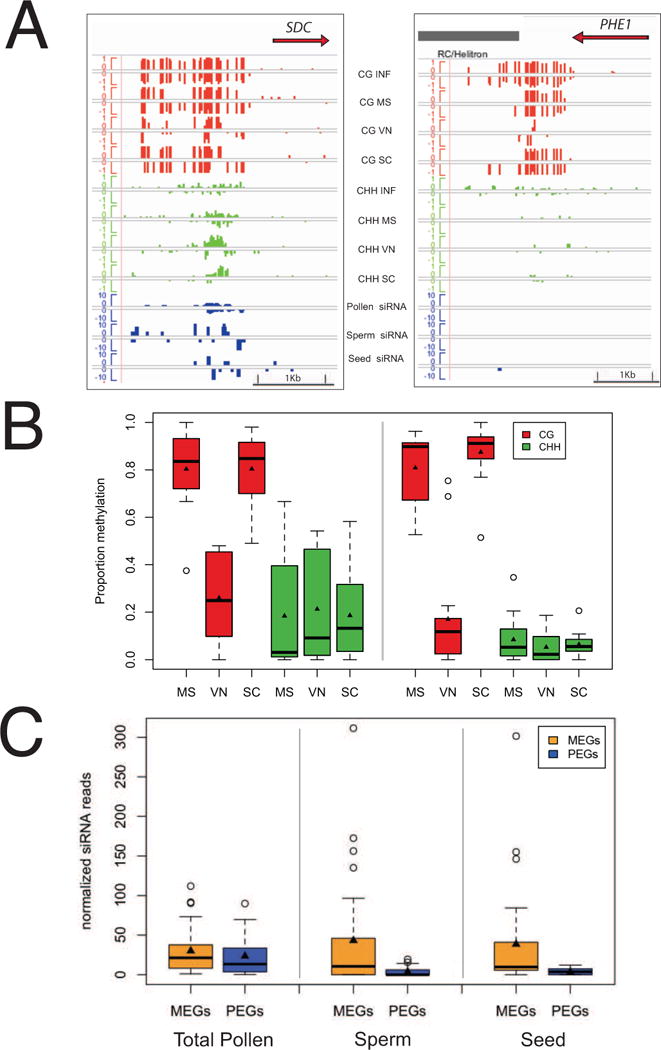

In somatic cells, the activity of DNA glycosylases such as ROS1, DML2 and DML3 results in loss of siRNA production as well as loss of DNA methylation, so that RDD targets tend to gain small RNAs in rdd mutants (Lister et al., 2008; Ortega-Galisteo et al., 2008). Sperm cells do not express DME, ROS1, DML2 and DML3 resembling rdd mutants in this respect, and we found that many DMRs that lost CG methylation in the VN accumulated siRNA in sperm cells (Figure 4). As many of these CG DMR flank imprinted genes (Gehring et al., 2009), we examined methylation patterns in repeats flanking the imprinted Maternally Expressed Gene (MEG) SUPPRESSOR OF DRM2/CMT3 (SDC) and the imprinted Paternally Expressed Gene (PEG) PHERES1 (PHE1) (Figure 5A). SDC is expressed when flanking repeats are unmethylated (Henderson and Jacobsen, 2008), but PHE1 is only expressed when a tandem repeat downstream of the coding sequence is methylated, likely because methylation prevents inhibition by the MEA/FIS2 Polycomb Group (PcG) complex (Makarevich et al., 2008). We found that tandem repeats flanking both genes lose CG methylation in the VN (Figure 5A). However, CHH methylation was only detected at SDC and not at PHE1. Furthermore, SDC accumulated 24nt siRNA in sperm cells (Figure 5A) unlike PHE1. The siRNA accumulated to even higher levels in total pollen grains, indicating they may (also) be generated in the VN.

Figure 5. DNA methylation and small RNA abundance at imprinted genes in pollen.

(A) Genome browser view of the Maternally Expressed Gene (MEG) SDC and the Paternally Expressed Gene (PEG) PHE1. Tracks display CG (red) and CHH (green) methylation as well as 24nt siRNAs (blue) from pollen, seeds and purified sperm cells. Methylation is represented on a scale of 0–100% and siRNAs for total normalized reads from 0–20 RPM (reads per million). MS (microspore), SC (sperm cell), VN (vegetative nucleus), INF (Inflorescence). (B) Box-plot representation of DNA methylation percentages at MEGs and PEGs. TEs neighboring both MEGs and PEGs are demethylated in the CG context specifically in the vegetative nucleus. Higher CHH methylation levels were detected at MEGs in comparison with PEGs. (C) Box plot representation of 24nt siRNA corresponding to TEs surrounding PEGs and MEGs in total pollen, sperm cells, and seeds. Boxes represent lower and upper quartiles surrounding the median (line). Triangles represent the mean.

We extended these observations to a larger number of putative imprinted genes (Gehring et al., 2011; Hsieh et al., 2011; McKeown et al., 2011; Wolff et al., 2011) filtered to include only experimentally validated PEGs and MEGs, resulting in 28 imprinted loci (12 MEGs and 16 PEGs) that passed our filter for methylation calls and had a TE within 2kb of the coding sequence (Table S3). All 28 TEs lost CG methylation in the VN relative to the progenitor microspore, but interestingly only those surrounding MEGs were targeted by siRNA and CHH methylation in pollen (Figure 5B). We plotted the size distribution of siRNA corresponding to CG DMRs, and found that while CG DMRs accumulated both 21 and 24nt siRNA in sperm cells, MEGs and PEGs accumulated only 24nt siRNA in sperm cells and in seeds (Figure 4). siRNA levels for MEGs were much higher than PEGs in sperm cells and in seeds, but not in total pollen (Figure 5C). We conclude that 24nt siRNA from repeats surrounding MEGs accumulate preferentially in sperm cells. It is possible that these are derived from the VN, resembling 21nt siRNA in this respect (Slotkin et al., 2009).

Reprogramming leads to spontaneous epigenetic variation

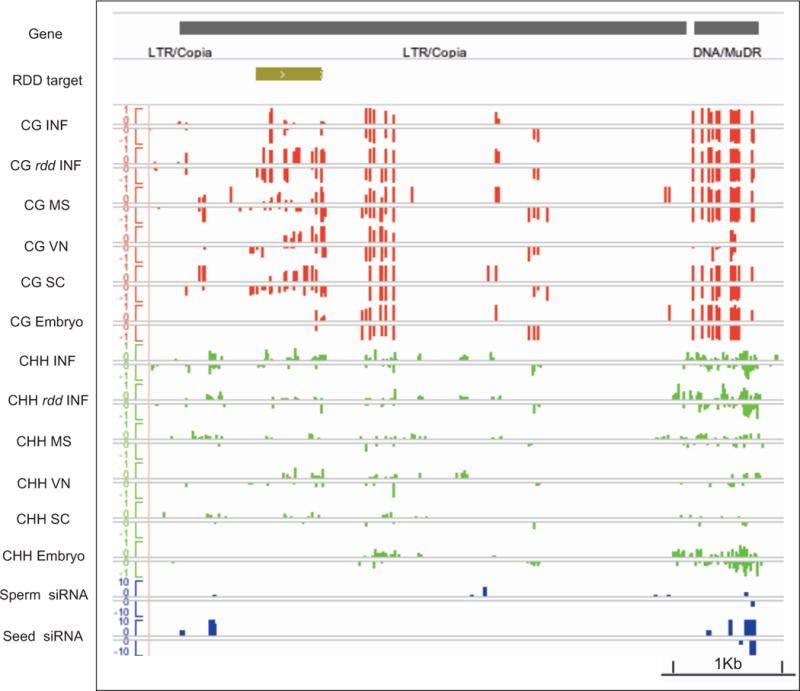

In plants, epigenetic changes in gene expression are frequently inherited from one generation to the next, and gains and losses of DNA methylation arise as spontaneous epigenetic variation (Martienssen and Colot, 2001). In two recent studies, more than 100 loci (DMRs) were found to gain DNA methylation sporadically in young leaf tissue after 30 generations of inbreeding by single seed descent (Becker et al., 2011; Schmitz et al., 2011). Methylation gains were recurrent, occurring at the same loci in multiple independent lines, leading to the proposal that methylation gains and losses might be pre-programmed in the germline (Schmitz et al., 2011). Among 100 hypervariable loci that gain methylation, we identified several ROS1/DML2/DML3 (RDD) targets that were completely re-methylated in rdd mutants compared to wild-type (Lister et al., 2008). Most of the remaining hypervariable loci already showed high methylation levels in wild-type inflorescence tissue (Lister et al., 2008). Remarkably, we observed that 56 of these 100 variable DMRs were hypermethylated in wild-type sperm cells. An example of a RDD target, corresponding to one of the hypervariable epialleles, is shown in Figure 6. This target is contained within a COPIA LTR retrotransposon (Atg409455) that is heavily methylated at CG sites in sperm cells, and less so in the microspore and VN (Figure 6). Further examples are shown in Figure S3. DME, ROS1, DML2 and DML3 are expressed at low levels in the microspore (Honys and Twell, 2004), and high levels in the VN (Schoft et al., 2011), accounting for differential CG methylation observed in sperm. Importantly, CG methylation found in sperm cells was removed in the embryo, reflecting the restoration of ROS1 activity after fertilization (Figure 6).

Figure 6. DNA methylation at hypervariable recurrent epialleles.

100 hypervariable epialleles gain DNA methylation recurrently in plants propagated by single seed descent (Becker et al., 2011; Schmitz et al., 2011). Many are targets of ROS1 and its homologs DML1 and DML2 (RDD). An example is shown (ATCOPIA51, At4g09455), along with a neighboring MuDR element for comparison. Tracks represent the RDD target region, and methylation levels in CG and CHH contexts in microspores (MS), vegetative nucleus (VN), and sperm cells (SC), along with inflorescence (INF) and embryo. CG methylation at the RDD target site is found in rdd triple mutant inflorescence (rdd INF) (Lister et al., 2008) and in pollen, but not in inflorescence or embryo. Small RNA from sperm cells (Slotkin et al., 2009) and seed (Lu et al., 2012) are also shown.

Discussion

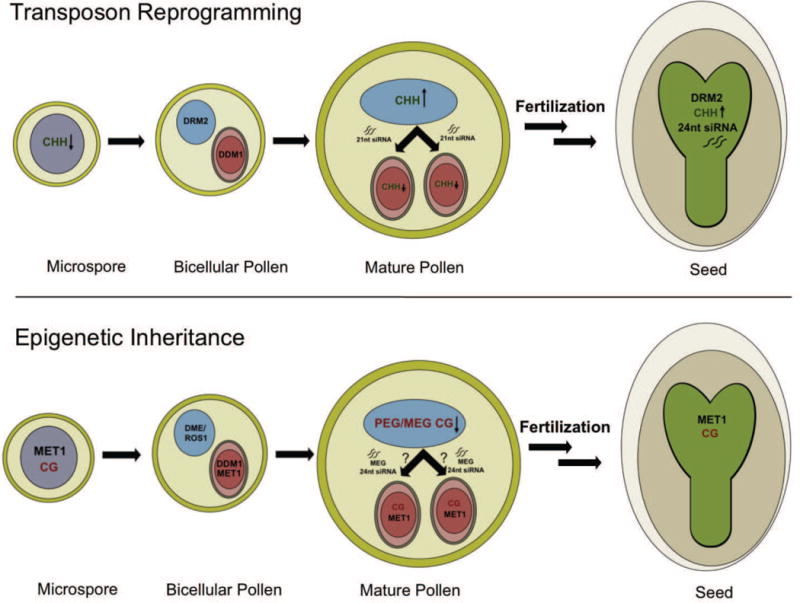

In mammals, 5-methylcytosine occurs mainly in symmetric CG dinucleotides, and is depleted in male primordial germ cells by loss of DNA methyltransferases and by active demethylation (Feng et al., 2010; Popp et al., 2010) resulting in TE activation (Castaneda et al., 2011). Methylation is restored in mature round spermatids (Feng et al., 2010; Popp et al., 2010) and then extensively modified by hydroxylation just before fertilization (Salvaing et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). Further rounds of methylation and demethylation occur in the blastocyst and early embryo (Feng et al., 2010) resulting in a complex pattern of DNA methylation that is reset in each generation (Bartolomei and Ferguson-Smith, 2011). In pollen, we have found that symmetric CG and CHG methylation are largely retained in the germline (Figure 7). This may account for the prevalence of epigenetic inheritance in plants, compared with mammals. Strikingly, however, asymmetric CHH methylation of transposons is reduced in the microspore, accompanied by down regulation of the RdDM methyltransferase DRM2, a homolog of the mammalian Dnmt3 (Figure 7). CHH methylation is restored in the embryo, and may reflect an ancient mechanism for transposon recognition.

Figure 7. Genome reprogramming during pollen development.

Differential expression of DRM2, MET1, ROS1, DME and DDM1 is depicted in bicellular pollen and persists in tricellular and mature pollen after the vegetative nucleus (VN, blue) and sperm cells (SC, red) differentiate (not shown). This results in reprogramming of transposons, imprinted genes and epialleles, as shown. Transposon reprogramming. DRM2 is down regulated in the microspore and sperm cells, so that CHH methylation is lost from retrotransposons, and is only restored after fertilization in the embryo (green), guided in part by maternal 24nt siRNA. DRM2 restores CHH methylation in the VN, guided by pollen 24nt siRNAs. In the vegetative cell, the chromatin remodeler DDM1 is lost, and retrotransposon activation generates 21nt siRNA that accumulate in sperm cells (arrow). Epigenetic inheritance. In the VN the DNA glycosylases DME and ROS1 target specific transposons for demethylation, including those that flank imprinted genes. In SC, CG methylation is maintained, and 24nt siRNA accumulate specifically from transposons that flank Maternally Expressed imprinted Genes (MEGs). These 24nt siRNAs may arise in the VN, resembling 21nt retrotransposon siRNA in this respect. A similar mechanism targets recurrent epialleles in pollen, contributing to their sporadic occurrence and to their subsequent inheritance in the embryo.

Transposon reprogramming in pollen

The loss of asymmetric CHH methylation in sperm cells means that paternal retrotransposons are delivered to the zygote stripped of CHH methylation. Restoration of DNA methylation in the embryo (Hsieh et al., 2009), indicates that CHH methylation must occur during or after fertilization, when the RdDM pathway is active (Jullien and Berger, 2012) (Figure 7). We demonstrate that 24nt siRNAs in seeds match retrotransposons that have lost CHH methylation in sperm (Figure 6). CHH methylation is restored in seeds (Hsieh et al., 2009), guided by these 24nt siRNAs (Jullien and Berger, 2012). It has been proposed that most 24nt small RNA in seeds are maternal in origin, especially in the seed coat and the endosperm (Mosher et al., 2009), and target retrotransposons (Lu et al., 2012). We can speculate that paternal retrotransposons that have lost CHH methylation, but do not match maternal siRNA, might escape silencing immediately after fertilization (Josefsson et al., 2006).

DRM2 expression is restored in the VN, and retrotransposons are remethylated in these companion cells (Figure 7), most likely at the bicellular stage when DCL3 and other components of the 24nt siRNA biogenesis pathway are expressed (Grant-Downton et al., 2009). However, TEs are strongly activated in the VN and give rise to mobile 21nt siRNA that accumulate in sperm cells (Slotkin et al., 2009). CHH methylation by RdDM would not be expected to prevent transcription in the absence of the chromatin remodeler DDM1 (Teixeira et al., 2009), which is not expressed in the VN, accounting for transposon activation (Slotkin et al., 2009). Loss of chromatin remodeling can result in transposon transcription even in the presence of DNA methylation (Lorkovic et al., 2012; Mittelsten Scheid et al., 2002; Moissiard et al., 2012; Vaillant et al., 2006). Furthermore, the VN undergoes extensive histone replacement, with the loss of many canonical histones including the centromeric histone CENH3, which may contribute to transposon activation (Berger and Twell, 2011; Schoft et al., 2009). It is possible therefore that CHH methylation in the VN compensates for the loss of pericentromeric heterochromatin (Schoft et al., 2009).

Reprogramming of imprinted genes

Although CG methylation was globally retained, a subset of DNA transposons, some non-LTR retrotransposons, and intergenic regions lost CG methylation in the VN (Figure 7). These transposons are targets of the DNA glycosylases DME, ROS1, DML2 and DML3, which are expressed in the VN. In sperm cells, these enzymes are not expressed, and 24nt siRNA corresponding to some of their targets accumulate, resembling ros1/dml2/dml3 triple mutants in this respect (Lister et al., 2008). This is particularly true for transposons that flank imprinted genes which are expressed from the maternal allele in the endosperm (MEGs), and imprinting at the SDC locus is lost in the endosperm when inherited from mutant pollen impaired in RdDM (Vu et al., 2012). These results indicate that 24nt siRNA in sperm cells contribute to RdDM and transcriptional silencing before fertilization in at least some cases (Figure 7). Like 21nt siRNA, these specific 24nt siRNA may also be derived from the VN, although this has not been tested directly (Figure 7). In this way, imprinted genes are protected from the global loss of methylation, reminiscent of mammalian imprinted genes, which regain methylation in the germline before fertilization (Feng et al., 2010).

Many imprinted genes are expressed in pollen (Table S3), and dme mutants are transmitted poorly because of defective pollen germination (Schoft et al., 2011). Similarly, ros1 mutants exhibit severe fertility defects after 3 generations of inbreeding (Gong et al., 2002). It is likely therefore that the targets of DME and ROS1 play a role in fertilization when the vegetative nucleus supports pollen tube growth (Berger and Twell, 2011). Silencing in sperm cells would restrict expression to the pollen tube, as well as resulting in imprinting in the endosperm. A small number of target were also demethylated in the microspore, and may have a function earlier in pollen development (Figure S2B).

Epigenetic inheritance in the plant germline

Similar silencing mechanisms may account for the methylation we observe in sperm at hypervariable epialleles. These epialleles acquire heritable methylation sporadically on inbreeding, prompting speculation that they might be reprogrammed in sperm (Becker et al., 2011; Schmitz et al., 2011). Some of these epialleles are silenced in ros1/dml2/dml3 mutants, and many correspond to TEs (Schmitz et al., 2011). We show that these variable epialleles are indeed methylated in sperm cells, and that many of them are methylated already in the inflorescence (Lister et al., 2008). Sperm cells do not express ROS1 and its homologs, accounting for higher methylation of RDD targets in sperm, and providing a mechanism for gain of heritable methylation if 24nt siRNA accumulate after fertilization to prevent demethylation by ROS1.

When transposon methylation is lost, it can be regained through RNAi (Teixeira et al., 2009) which seems to occur stepwise in subsequent generations consistent with its occurrence in the germline (Teixeira and Colot, 2010). Loss and gain of class II DNA transposon activity in maize occurs over generations (McClintock, 1965), during development (Li et al., 2010; Martienssen and Baron, 1994; Martienssen and Colot, 2001) and is inherited in the germline resembling the epialleles recently described in Arabidopsis (Becker et al., 2011; Schmitz et al., 2011). Our results suggest that similar epigenetic mechanisms silence epialleles and imprinted genes in pollen, which escape reprogramming in subsequent generations because of the retention of DNA methylation in sperm.

Materials and Methods

Cell sorting by FACS

A detailed protocol for isolation of sperm cells, vegetative nuclei and microspores by Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) will be published elsewhere (Borges et al., 2012). In brief, open flowers from transgenic plants expressing MGH3p-MGH3-GFP (MGH3/HTR10, At1g19890) and ACT11p-H2B-mRFP (ACT11, At3g12110) transgenes were collected into a 2mL eppendorf tube. The tissue was vigorously vortexed in Galbraith buffer (45mM MgCl2, 30mM Sodium Citrate, 20mM MOPS, 1% Triton-100, pH to 7.0) for 3 minutes to release mature pollen (Galbraith et al., 1983). This crude fraction was then filtered though a 30 micron mesh into a tube containing 100uL of glass beads, and vortexed for additional 3 minutes in order to break the pollen cell wall. Sperm cells and VN were then isolated by FACS based on their distinct fluorescent signals (Borges et al., 2012). In order to isolate microspores, young flower buds were gently ground in a mortar and pestle in pollen extraction buffer (PEB: 10mM CaCl2, 2mM MES, 1mM KCl, 1% H3BO3, 10% Sucrose, pH 7.5) in order to release the spores (Becker et al., 2003). This crude fraction was initially filtered through Miracloth to remove larger debris, and concentrated by centrifugation (800g, 5 min). The resulting pellet enriched in pollen spores was resuspended in 1–2mL of PEB, and filtered through a 20 micron mesh before FACS. Microspores were sorted based on their small size and autofluorescent properties (Borges et al., 2012).

Library preparation from bisulfite treated DNA

Genomic DNA was isolated from approximately 600,000 sperm cells, 300,000 vegetative nuclei and 1,000,000 microspores isolated by FACS (Borges et al., 2012) and fragmented by Covaris in 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Fragments were end repaired, A-tailed and ligated to methylated Illumina adaptors. Ligated fragments were bisulfite treated using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo), and PCR enriched with Expand High-Fidelity Polymerase (Roche). Amplified fragments of 340–360bp were size selected by gel extraction, and sequenced on an Illumina GAII platform as paired end 50 nt (PE50) reads.

Identification of methylated cytosines

To test whether each cytosine (covered by at least four reads) was methylated, the proportion of methylated reads to un-methylated reads was compared to the background error rate using a binomial test. The background false positive error rate (sequencing errors + conversion errors) was calculated using reads mapping to the unmethylated chloroplast genome. The number of methylated cytosines was calculated independently for each library. Correction for multiple testing was performed using Storey’s q-values (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003) with an FDR of 0.05. The circos plot (www.circos.ca) was calculated as follows: The mean methylation across 10kb windows was calculated separately for each methylation context. Heatmaps were scaled based on the maximum level of methylation found within each methylation context across all tissues tested (CG: 0 to 0.95, CHG: 0 to 0.83 and CHH: 0 to 0.34).

Identification of Single Methylation Polymorphisms (SMPs)

For each pairwise comparison (VN vs. SC, VN vs. microspore and SC vs. microspore) the union of methylated cytosines were tested for SMPs using Fisher’s exact test. For CpG and CHG (symmetrical) contexts, reads from both strands were used. For CHH (non-symmetrical) contexts, each strand was interrogated independently. Correction for multiple testing was performed using Storey’s q-values. For CHH methylation a FDR of 0.05 was used. For CG and CHG methylation an FDR of 0.1 was used to reflect the more subtle changes in methylation expected.

Identification and analysis of Differentially Methylated Regions (DMRs)

For CHH methylation, putative DMRs were defined as regions containing at least five SMPs each < 50bp away from its neighboring SMP and containing a minimum of ten methylated cytosines. For CG and CHG methylation, putative DMRs were defined as regions containing at least three SMPs each < 50bp from its neighboring SMPs and containing at least five methylated cytosines. These regions were tested using the sum of reads (methylated and un-methylated) across the region using Fisher’s exact test.

DMR were detected in published genome-wide methylation profiles using the same pipeline. This analysis uncovered 1624 CG DMRs between ros1/dml2/dml3 inflorescence and wild type inflorescence (Lister et al., 2008), and 171 DMRs between endosperm vs. dme mutant endosperm (Hsieh et al., 2009). This combined list was compared to regions of differential methylation between VN vs. SC and VN vs. microspore. We found an overlap of 131 of the 221 (60%) CG DMRs observed between SC and VN, and 83 of 164 (51%) CG DMRs observed between SC and microspore. When the list was refined to include only TEs, the overlap was (85%) as described in the text (Figure 2B).

Analysis of small RNA

Small RNAs from sperm (Slotkin et al., 2009) and seed (Lu et al., 2012) were collapsed and mapped to the Arabidopsis genome (TAIR10). All 20–25 nt smallRNAs overlapping CHH and CG DMRs, plus TEs within 2kb of MEGs and PEGs were then identified. The size distribution of those overlapping small RNAs was then calculated for each genomic feature. In purified SC, the median number of reads mapping to MEG TEs is 10.53 (Q1: 0, Q3: 46.07) per MEG and a median of 0.0 (Q1: 0.0, Q3: 6.142) for PEGs. In total pollen, the median number of mapping reads to MEG TEs is 21.34 (Q1: 8.326, Q3: 36.876) per MEG and a median of 13.4519 (Q1: 3.6158, Q3: 33.703) for PEG TEs. In seeds, the median number of mapping reads to MEG TEs is 9.764 (Q1: 5.633, Q3: 41.012) per MEG and a median of 3.755 (Q1: 0.0, Q3: 7.041) for PEG TEs.

Methyltransferase gene fusions

pDRM2-DRM2:GFP was generated as described (Jullien and Berger, 2012). At least ten transgenic lines were analyzed and showed a consistent pattern of expression of the fluorescent reporter. Three complementing lines were used for further detailed analysis. The expression pattern of DNA methyltransferases in pollen was observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope Zeiss LSM510.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Loss of CHH methylation at the pericentromeric LTR retrotransposon Athila6A. A genome browser view of an Athila element from chromosome 4. Methylated cytosines in CG and CHH contexts are shown wild-type (INF) and rdd mutant inflorescence (rdd INF), microspore (MS), vegetative nucleus (VN), sperm cells (SC) and Embryo. CG methylation is maintained in the three cell types throughout pollen development relative to the wild-type inflorescence. CHH methylation is reduced in the microspore and sperm cells, but restored in the VN in the embryo. Small RNAs reads corresponding to SC and seed are presented. 21nt small RNA were detected in sperm cells as previously reported (Slotkin et al., 2009).

Figure S2. Demethylation in the vegetative cell and in the microspore. (A) CG DMRs in the vegetative nucleus (VN) vs microspore (MS) (blue) overlap with DMRs detected between WT endosperm and dme endosperm (green), which are targets of DEMETER (Hsieh et al., 2009), and with DMR detected between WT inflorescence and ros1/dml2/dml3 inflorescence (Lister et al., 2008), which are targets of ROS1 and its homologs (orange). These targets lose methylation in the VN. (B) CG DMRs in the MS vs sperm cells (SC), these regions lose methylation before pollen mitosis I and are predominately targets of ROS1 and its homologs.

Figure S3. Examples of hypervariable epialleles corresponding to targets of the DNA glycosylases ROS1, DML2 and DML3 (RDD). Genome browser views of two genes that overlap hypervariable epialleles (Becker et al., 2011; Schmitz et al., 2011) corresponding to targets of the RDD glycosylases (“RDD targets”). Methylated cytosines in CG and CHH contexts are shown in microspore (MS), vegetative nucleus (VN) and sperm cells (SC), as well as in inflorescence (INF) and inflorescence from triple ros1/dml2/dml3 DNA glycosylase mutants (rdd INF), and embryo. RDD targets gain methylation in rdd inflorescence (Lister et al., 2008), but are unmethylated in embryo and wild-type inflorescence. These genes are fully methylated in SC and in the VN but not in MS cells. In both examples, CG methylation in the WT inflorescence is also increased suggesting methylation may have already occurred during flower development. The presence of siRNA may protect the allele from ROS1 activity after fertilization, resulting in the inheritance of DNA methylation.

Table S1. Sequencing statistics, reads, coverage depth and coverage width. % mC is tabulated in each sequence context, CG, CHG and CHH, where H = A,C or T.

Table S2. Differentially Methylated Regions in each sequence context, annotated by Transposable Element class.

Table S3. Imprinted genes used in this study. Validated Maternally Expressed Genes (MEGs) and Paternally Expressed Genes (PEGs) were filtered for adequate bisulfite sequencing coverage. Most are expressed during pollen development, either in mature pollen (MP), in sperm cells (SC), microspores (UNM) and/or bicellular pollen (BCP). Signal expression values are shown along with absence/presence calls (Borges et al., 2008; Honys and Twell, 2004).

Table S4. DMRs corresponding to hypervariable epialleles. Hypervariable epiallelic loci that gain methylation in inbred lines derived by single seed descent (Becker et al., 2011) are tabulated according to genome co-ordinates, methylation levels in leaf, sperm cells, vegetative nuclei and microspores.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Regulski, Jude Kendall, Evan Ernst, Emily Hodges and Antoine Molaro for advice with bisulfite sequencing and analysis, Vincent Colot, Arp Schnittger and Daniel Bouyer for helpful discussions and Shiran Pasternak for help with graphic presentation. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 GM067014 to RM, grants PTDC/AGR-GPL/103778/2008 and PTDC/BIA-BCM/103787/2008 from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) to JDB and FCT grant PTDC/BIA-BCM/108044/2008 to JAF. FB and PJ were supported by Temasek Lifescience Laboratory. JPC was supported by a graduate student fellowship from NSERC and by a grant from the Fred C. Gloeckner Foundation, F. Borges was supported by a FCT PhD fellowship SFRH/BD/48761/2008, and FVE was funded by a Herbert Hoover postdoctoral fellowship from the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bartolomei MS, Ferguson-Smith AC. Mammalian genomic imprinting. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a002592. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C, Hagmann J, Muller J, Koenig D, Stegle O, Borgwardt K, Weigel D. Spontaneous epigenetic variation in the Arabidopsis thaliana methylome. Nature. 2011;480:245–249. doi: 10.1038/nature10555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JD, Boavida LC, Carneiro J, Haury M, Feijo JA. Transcriptional profiling of Arabidopsis tissues reveals the unique characteristics of the pollen transcriptome. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:713–725. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.028241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger F, Twell D. Germline specification and function in plants. Annu Rev. Plant Biol. 2011;62:461–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boavida LC, Becker JD, Feijo JA. The making of gametes in higher plants. Int J Dev Biol. 2005;49:595–614. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052019lb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges F, Gardner R, Lopes T, Calarco JP, Slotkin RK, Martienssen RA, Becker JD. FACS-based Purification of Arabidopsis Microspores, Sperm Cells and Vegetative Nuclei. BMC Plant Methods. 2012 doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-8-44. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges F, Gomes G, Gardner R, Moreno N, McCormick S, Feijo JA, Becker JD. Comparative Transcriptomics of Arabidopsis thaliana Sperm Cells. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1168–1181. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.125229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Jacobsen SE. Role of the arabidopsis DRM methyltransferases in de novo DNA methylation and gene silencing. Current Biology. 2002;12:1138–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda J, Genzor P, Bortvin A. piRNAs, transposon silencing, and germline genome integrity. Mutat Res. 2011;714:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokus SJ, Feng S, Zhang X, Chen Z, Merriman B, Haudenschild CD, Pradhan S, Nelson SF, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE. Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature. 2008;452:215–219. doi: 10.1038/nature06745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubas P, Vincent C, Coen E. An epigenetic mutation responsible for natural variation in floral symmetry. Nature. 1999;401:157–161. doi: 10.1038/43657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Jacobsen SE, Reik W. Epigenetic reprogramming in plant and animal development. Science. 2010;330:622–627. doi: 10.1126/science.1190614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith DW, Harkins KR, Maddox JM, Ayres NM, Sharma DP, Firoozabady E. Rapid flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle in intact plant tissues. Science. 1983;220:1049–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.220.4601.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring M, Bubb KL, Henikoff S. Extensive demethylation of repetitive elements during seed development underlies gene imprinting. Science. 2009;324:1447–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1171609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring M, Missirian V, Henikoff S. Genomic analysis of parent-of-origin allelic expression in Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z, Morales-Ruiz T, Ariza RR, Roldan-Arjona T, David L, Zhu JK. ROS1, a repressor of transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis, encodes a DNA glycosylase/lyase. Cell. 2002;111:803–814. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant-Downton R, Hafidh S, Twell D, Dickinson HG. Small RNA pathways are present and functional in the angiosperm male gametophyte. Mol Plant. 2009;2:500–512. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag JR, Pikaard CS. Multisubunit RNA polymerases IV and V: purveyors of non-coding RNA for plant gene silencing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:483–492. doi: 10.1038/nrm3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE. Tandem repeats upstream of the Arabidopsis endogene SDC recruit non-CG DNA methylation and initiate siRNA spreading. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1597–1606. doi: 10.1101/gad.1667808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honys D, Twell D. Transcriptome analysis of haploid male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Genome Biology. 2004;5:R85. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-11-r85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh TF, Ibarra CA, Silva P, Zemach A, Eshed-Williams L, Fischer RL, Zilberman D. Genome-wide demethylation of Arabidopsis endosperm. Science. 2009;324:1451–1454. doi: 10.1126/science.1172417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh TF, Shin J, Uzawa R, Silva P, Cohen S, Bauer MJ, Hashimoto M, Kirkbride RC, Harada JJ, Zilberman D, et al. Regulation of imprinted gene expression in Arabidopsis endosperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1755–1762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019273108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefsson C, Dilkes B, Comai L. Parent-dependent loss of gene silencing during interspecies hybridization. Current Biology. 2006;16:1322–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullien PE, Berger F. Gamete-specific epigenetic mechanisms shape genomic imprinting. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12:637–642. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullien PE, Berger F. DNA methylation dynamics during sexual reproduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Current Biology. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.07.061. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullien PE, Kinoshita T, Ohad N, Berger F. Maintenance of DNA methylation during the Arabidopsis life cycle is essential for parental imprinting. Plant Cell. 2006;18:1360–1372. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.041178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law JA, Jacobsen SE. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Freeling M, Lisch D. Epigenetic reprogramming during vegetative phase change in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:22184–22189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016884108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman Z, Gendrel AV, Black M, Vaughn MW, Dedhia N, McCombie WR, Lavine K, Mittal V, May B, Kasschau KD, et al. Role of transposable elements in heterochromatin and epigenetic control. Nature. 2004;430:471–476. doi: 10.1038/nature02651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lister R, O’Malley RC, Tonti-Filippini J, Gregory BD, Berry CC, Millar AH, Ecker JR. Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2008;133:523–536. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorkovic ZJ, Naumann U, Matzke AJ, Matzke M. Involvement of a GHKL ATPase in RNA-directed DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Current Biology. 2012;22:933–938. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Zhang C, Baulcombe DC, Chen ZJ. Maternal siRNAs as regulators of parental genome imbalance and gene expression in endosperm of Arabidopsis seeds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5529–5534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203094109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarevich G, Villar CB, Erilova A, Kohler C. Mechanism of PHERES1 imprinting in Arabidopsis. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:906–912. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen R, Barkan A, Taylor WC, Freeling M. Somatically heritable switches in the DNA modification of Mu transposable elements monitored with a suppressible mutant in maize. Genes Dev. 1990;4:331–343. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen R, Baron A. Coordinate suppression of mutations caused by Robertson’s mutator transposons in maize. Genetics. 1994;136:1157–1170. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen RA, Colot V. DNA methylation and epigenetic inheritance in plants and filamentous fungi. Science. 2001;293:1070–1074. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5532.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B. The control of gene action in maize. Brookhaven Symposia in. Biology. 1965;18:162–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown PC, Laouielle-Duprat S, Prins P, Wolff P, Schmid MW, Donoghue MT, Fort A, Duszynska D, Comte A, Lao NT, et al. Identification of imprinted genes subject to parent-of-origin specific expression in Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelsten Scheid O, Probst AV, Afsar K, Paszkowski J. Two regulatory levels of transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13659–13662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202380499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moissiard G, Cokus SJ, Cary J, Feng S, Billi AC, Stroud H, Husmann D, Zhan Y, Lajoie BR, McCord RP, et al. MORC family ATPases required for heterochromatin condensation and gene silencing. Science. 2012;336:1448–1451. doi: 10.1126/science.1221472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher RA, Melnyk CW, Kelly KA, Dunn RM, Studholme DJ, Baulcombe DC. Uniparental expression of PolIV-dependent siRNAs in developing endosperm of Arabidopsis. Nature. 2009;460:283–286. doi: 10.1038/nature08084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Galisteo AP, Morales-Ruiz T, Ariza RR, Roldan-Arjona T. Arabidopsis DEMETER-LIKE proteins DML2 and DML3 are required for appropriate distribution of DNA methylation marks. Plant Mol Biol. 2008;67:671–681. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pina C, Pinto F, Feijo JA, Becker JD. Gene family analysis of the Arabidopsis pollen transcriptome reveals biological implications for cell growth, division control, and gene expression regulation. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:744–756. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.057935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp C, Dean W, Feng S, Cokus SJ, Andrews S, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE, Reik W. Genome-wide erasure of DNA methylation in mouse primordial germ cells is affected by AID deficiency. Nature. 2010;463:1101–1105. doi: 10.1038/nature08829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford EJ, Ferron SR, Ferguson-Smith AC. Genomic imprinting as an adaptative model of developmental plasticity. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2059–2066. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raissig MT, Baroux C, Grossniklaus U. Regulation and flexibility of genomic imprinting during seed development. Plant Cell. 2011;23:16–26. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.081018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvaing J, Aguirre-Lavin T, Boulesteix C, Lehmann G, Debey P, Beaujean N. 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine spatiotemporal profiles in the mouse zygote. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saze H, Scheid OM, Paszkowski J. Maintenance of CpG methylation is essential for epigenetic inheritance during plant gametogenesis. Nat Genet. 2003;34:65–69. doi: 10.1038/ng1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz RJ, Schultz MD, Lewsey MG, O’Malley RC, Urich MA, Libiger O, Schork NJ, Ecker JR. Transgenerational Epigenetic Instability Is a Source of Novel Methylation Variants. Science. 2011;334:369–373. doi: 10.1126/science.1212959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoft VK, Chumak N, Choi Y, Hannon M, Garcia-Aguilar M, Machlicova A, Slusarz L, Mosiolek M, Park JS, Park GT, et al. Function of the DEMETER DNA glycosylase in the Arabidopsis thaliana male gametophyte. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8042–8047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105117108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoft VK, Chumak N, Mosiolek M, Slusarz L, Komnenovic V, Brownfield L, Twell D, Kakutani T, Tamaru H. Induction of RNA-directed DNA methylation upon decondensation of constitutive heterochromatin. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1015–1021. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin RK, Vaughn M, Borges F, Tanurdzic M, Becker JD, Feijo JA, Martienssen RA. Epigenetic reprogramming and small RNA silencing of transposable elements in pollen. Cell. 2009;136:461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira FK, Colot V. Repeat elements and the Arabidopsis DNA methylation landscape. Heredity. 2010;105:14–23. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira FK, Heredia F, Sarazin A, Roudier F, Boccara M, Ciaudo C, Cruaud C, Poulain J, Berdasco M, Fraga MF, et al. A role for RNAi in the selective correction of DNA methylation defects. Science. 2009;323:1600–1604. doi: 10.1126/science.1165313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant I, Schubert I, Tourmente S, Mathieu O. MOM1 mediates DNA-methylation-independent silencing of repetitive sequences in Arabidopsis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:1273–1278. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu TM, Nakamura M, Calarco JP, Susaki D, Lim PQ, Kinoshita T, Higashiyama T, Martienssen R, Berger F. RNA-directed DNA methylation controls parental imprinting in Arabidopsis. 2012. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff P, Weinhofer I, Seguin J, Roszak P, Beisel C, Donoghue MT, Spillane C, Nordborg M, Rehmsmeier M, Kohler C. High-resolution analysis of parent-of-origin allelic expression in the Arabidopsis Endosperm. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Su L, Wang Z, Zhang S, Guan J, Chen Y, Yin Y, Gao F, Tang B, Li Z. The involvement of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in active DNA demethylation in mice. Biol Reprod. 2012;86:104. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.096073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Loss of CHH methylation at the pericentromeric LTR retrotransposon Athila6A. A genome browser view of an Athila element from chromosome 4. Methylated cytosines in CG and CHH contexts are shown wild-type (INF) and rdd mutant inflorescence (rdd INF), microspore (MS), vegetative nucleus (VN), sperm cells (SC) and Embryo. CG methylation is maintained in the three cell types throughout pollen development relative to the wild-type inflorescence. CHH methylation is reduced in the microspore and sperm cells, but restored in the VN in the embryo. Small RNAs reads corresponding to SC and seed are presented. 21nt small RNA were detected in sperm cells as previously reported (Slotkin et al., 2009).

Figure S2. Demethylation in the vegetative cell and in the microspore. (A) CG DMRs in the vegetative nucleus (VN) vs microspore (MS) (blue) overlap with DMRs detected between WT endosperm and dme endosperm (green), which are targets of DEMETER (Hsieh et al., 2009), and with DMR detected between WT inflorescence and ros1/dml2/dml3 inflorescence (Lister et al., 2008), which are targets of ROS1 and its homologs (orange). These targets lose methylation in the VN. (B) CG DMRs in the MS vs sperm cells (SC), these regions lose methylation before pollen mitosis I and are predominately targets of ROS1 and its homologs.

Figure S3. Examples of hypervariable epialleles corresponding to targets of the DNA glycosylases ROS1, DML2 and DML3 (RDD). Genome browser views of two genes that overlap hypervariable epialleles (Becker et al., 2011; Schmitz et al., 2011) corresponding to targets of the RDD glycosylases (“RDD targets”). Methylated cytosines in CG and CHH contexts are shown in microspore (MS), vegetative nucleus (VN) and sperm cells (SC), as well as in inflorescence (INF) and inflorescence from triple ros1/dml2/dml3 DNA glycosylase mutants (rdd INF), and embryo. RDD targets gain methylation in rdd inflorescence (Lister et al., 2008), but are unmethylated in embryo and wild-type inflorescence. These genes are fully methylated in SC and in the VN but not in MS cells. In both examples, CG methylation in the WT inflorescence is also increased suggesting methylation may have already occurred during flower development. The presence of siRNA may protect the allele from ROS1 activity after fertilization, resulting in the inheritance of DNA methylation.

Table S1. Sequencing statistics, reads, coverage depth and coverage width. % mC is tabulated in each sequence context, CG, CHG and CHH, where H = A,C or T.

Table S2. Differentially Methylated Regions in each sequence context, annotated by Transposable Element class.

Table S3. Imprinted genes used in this study. Validated Maternally Expressed Genes (MEGs) and Paternally Expressed Genes (PEGs) were filtered for adequate bisulfite sequencing coverage. Most are expressed during pollen development, either in mature pollen (MP), in sperm cells (SC), microspores (UNM) and/or bicellular pollen (BCP). Signal expression values are shown along with absence/presence calls (Borges et al., 2008; Honys and Twell, 2004).

Table S4. DMRs corresponding to hypervariable epialleles. Hypervariable epiallelic loci that gain methylation in inbred lines derived by single seed descent (Becker et al., 2011) are tabulated according to genome co-ordinates, methylation levels in leaf, sperm cells, vegetative nuclei and microspores.