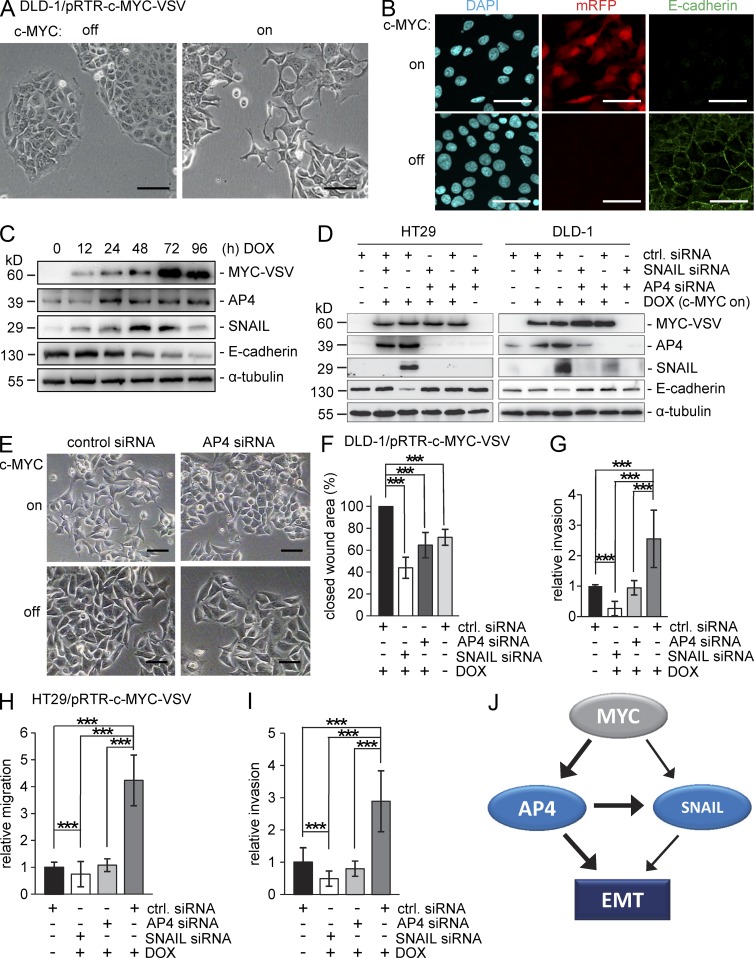

Figure 8.

A circuitry involving c-MYC, AP4, and SNAIL regulates EMT and invasion. (A) Representative phase-contrast pictures of DLD-1/pRTR–c-MYC–VSV cells after addition of DOX for 96 h. (B) Confocal microscopy analysis 96 h after DOX treatment as in Fig. 5 (C–E). (C) Protein lysates obtained after DOX treatment for the indicated periods were subjected to immunoblot analysis. Detection of α-tubulin served as a loading control. (D and E) Immunoblot analysis of the indicated cell lines 96 h after c-MYC activation by DOX and concomitant siRNA transfection (D) and phase-contrast microscopy of DLD-1/pRTR–c-MYC–VSV cells 96 h after addition of DOX and/or transfection with the indicated siRNAs (E). (A, B, and E) Bars, 50 µm. (F) 72 h after c-MYC activation and/or transfection with the indicated siRNAs, cells were subjected to a wound healing assay. Wound closure was determined 48 h after scratching. (G) Cellular invasion was determined in a transwell Boyden chamber assay 96 h after addition of DOX and/or transfection with the indicated siRNAs. After 48 h, cells were fixed and stained with DAPI. The mean number of cells in five fields per membrane was counted in three different inserts. (H and I) Cellular migration (H) and invasion (I) of HT29 ectopically expressing c-MYC as described in G. Relative invasion or migration is expressed as the value of test cells to control cells. (J) Schematic model of the c-MYC/AP4/SNAIL circuitry. (D–G) For siRNA transfections, identical total siRNA concentrations (20 nM) were achieved by reconstitution with control siRNA. (F–I) Experiments were performed in triplicates (n = 3); error bars indicate SD; significance level as indicated: ***, P < 0.001.