Abstract

Most incarcerated individuals will return to the community, and their successful reentry requires consideration of their health and how their health will affect their families and communities. We propose the use of a prevention science framework that integrates universal, selective, and indicated strategies to facilitate the successful reentry of men released from prison. Understanding how health risks and disparities affect the transition from prison to the community will enhance reentry intervention efforts. To explore the application of the prevention rubric, we evaluated a community-based prisoner reentry initiative. The findings challenge all involved in reentry initiatives to reconceptualize prisoner reentry from a program model to a prevention model that considers multilevel risks to and facilitators of successful reentry.

The economic and social costs of incarceration necessitate efforts to promote successful reintegration into the community. Changes in sentencing, release, and community supervision policies and practices have led to an increase in prison populations, overrepresentation of people of color in correctional facilities, and a subsequent increase in the number of individuals returning to the community from prison (D. M. G., L. N.W., and W. D., unpublished manuscript, March 2007).1 Ninety-five percent of the more than 2 million adults who are incarcerated in the United States will be released from prison,2,3 and most will face a variety of reintegration challenges. Those who are at highest risk for unsuccessful return to the community are single men of color who do not participate in educational or vocational courses in prison, do not seek or do not obtain employment following release, have a history of substance abuse, and are repeat offenders.4–6 A critical component of this profile is insufficient resources, opportunities, and supports. When individuals are not adequately supported in their transitions, the impact is significant for them, their families, the community, and the criminal justice system.

One of the unintentional consequences of incarceration is the impact on the health and functioning of those incarcerated and their social networks.7–10 Because men of color are disproportionately incarcerated, the health and social effects of incarceration are particularly devastating in these communities.10–12 Thus, addressing prison reentry is an essential strategy to address health disparities and increase health equity. Any intervention focusing on health for these communities must consider the role of incarceration in the observed differences in morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, increasing the health of formerly incarcerated men can positively affect the health of the communities to which they return.13

Recognizing the barriers faced by the formerly incarcerated, some have called for interventions that specifically target those risks.10,13–16 The transition from prison to the community presents a unique opportunity for prevention efforts to address the needs of formerly incarcerated individuals, including their health-related needs. We propose applying a prevention science framework to reentry initiatives to reduce the barriers to reintegration and the physical, mental, and emotional health risks that formerly incarcerated men face. We present observations from an ongoing evaluation of a pilot reentry program to illuminate strengths and areas of development for recidivism prevention initiatives. We also offer recommendations for strengthening the ability of reentry initiatives to facilitate the successful reentry of individuals returning to the community from prison.

APPLYING PREVENTION SCIENCE PRINCIPLES TO REENTRY

Central to public health approaches to prevention science is a focus on etiology and intervention development and implementation. Once malleable risk and protective factors are identified, preventive interventions are planned to prevent disorders, reduce risks, and promote health, taking into consideration the cultural and community context in which the interventions will be implemented.17,18 The principles of prevention therefore apply to prisoner reentry. Formerly incarcerated individuals face a variety of barriers to successful and permanent reentry that can be reduced when anticipated and adequately addressed. Consistent with an ecological prevention framework that considers the individual- to societal-level factors that influence risk,17,19 providing multilevel supports prior to release helps prisoners, service providers, community supports, and correctional staff anticipate and prepare for the transition to the community. Strengths-based universal, selective, and indicated preventive interventions are needed to help formerly incarcerated individuals reduce their risks for unsuccessful reentry. Universal preventive interventions are directed at the entire population of interest, selective interventions are for a subgroup of the population that is at increased risk of difficulties, and indicated interventions are designed for those at greatest risk.20,21

Conceptualizing both barriers to and facilitators of reentry from a universal, selective, and indicated level of risk perspective is critical to understanding formerly incarcerated individuals’ strengths and needs and to developing effective interventions to address them. A prevention framework provides structure not only to plan for treatment and immediate needs but also to anticipate a broader array of challenges, identify strengths and resources (e.g., education, informal supports) to overcome those challenges, and help all individuals prepare for their reintegration into the community. This framework can increase awareness of the importance of promoting the health of all returning to the community—not just those with acute or chronic conditions—and takes into account all areas of individuals’ lives that affect their health and that will change when they return to the community.

BARRIERS TO REENTRY

All levels of risk—universal, selective, and indicated—can affect the health of individuals returning to the community from prison. These risks encompass not only needs related to the health system but also social determinants of health that affect the formerly incarcerated. From a universal perspective, all individuals returning to the community from prison will need access to health care, housing, employment, and social support. Economic and social instability are primary barriers to successful reentry into the community. Individuals’ criminal charge history and legal status often limit their employment opportunities, also limiting their access to health insurance or their means to pay for care. Incarceration can jeopardize released individuals’ roles in their families and can impose emotional and financial strain on family members.22,23 Furthermore, informal supports such as community organizations may feel mistrustful of formerly incarcerated individuals.24 The return of large numbers of individuals to the community from prison can negatively affect the health, stability, cohesion, organization, and economic well-being of the community.25–27

From a selective perspective, a subgroup of formerly incarcerated individuals has specific needs that place them at increased risk of recidivism. For instance, environmental and social factors (e.g., housing) affect individuals’ health, and formerly incarcerated individuals often return to environments that jeopardize their health.14,28 The communities to which individuals return are often resource poor and have high rates of violence or other environmental hazards (D. M.G., L. N.W., and W. D., unpublished manuscript, March 2007). Many incarcerated individuals also have less education, fewer job skills, and a more limited work history than do individuals in the community, which can decrease their earning potential, financial stability, and access to health care services.13,27 In addition, substance abuse and dependence significantly affect the recidivism of formerly incarcerated individuals.27,29 Substance abuse is a selective risk in this population, with research indicating that more than 75% of inmates have a history of substance abuse.30 (However, substance abuse and dependence are indicated risks in the general population, with a prevalence of 13% among men.31)

From an indicated perspective, the economic and social challenges to reintegration are exacerbated when an individual’s health is compromised, making health a risk for the subset of released individuals with acute and chronic health conditions. Acute and chronic physical and mental illnesses as well as substance abuse can impede individuals’ ability to surmount other barriers to reentry, thereby increasing their risk of relapse and recidivism.16,32,33 A disproportionate number of medical problems and psychiatric difficulties exist in prison, such that the health of prisoners is comparable to that of individuals in the community who are 10 years their senior.13,30,32 Infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, hepatitis, and tuberculosis are particularly common.30,33 Prisoners are significantly more likely than members of the general population to be diagnosed with a severe mental disorder.7,29,34 Psychiatric and substance abuse disorders can be exacerbated by incarceration and overcrowding. Prisoners typically receive treatment only for disorders that are severe or were present at the time of the offense; inadequate treatment planning often further worsens their health.29,35

The higher prevalence of physical and mental conditions among the prison population, coupled with the racial/ethnic disparities in health and in incarceration rates, put men of color at even greater risk.28,36 Stigma, mistrust of the health system, socialization, masculinity, and shame and guilt can cause men—particularly African Americans and Latinos—to be unwilling to seek care.37–40 Returning to the community without medical services and other necessary supports can contribute to the spread of infectious diseases, decompensation, and relapse.27,30,33,41

CURRENT REENTRY PRACTICES

Best practice in preventive reentry interventions encompasses environmental and systemic strategies and policies to promote successful reintegration and to decrease recidivism.42 Best practice also includes reentry processes that begin prior to release from prison, are connected to the community, and build on individuals’ strengths while attending to the needs that affect successful reintegration.24,26,30,43 To be effective, reentry interventions must also be culturally competent and appropriate and consider racial/ethnic disparities and the particular needs, strengths, and resources of diverse groups.22,23,26,44 Research and policy (e.g., the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) suggest that cultural competency is critical to effective services generally and is particularly critical to reducing health disparities and increasing health equity.45,46

Pre- and postrelease services that focus on vocational skills, housing, and substance abuse have been found effective.27,47,48 Yet comprehensive and integrated program models that not only focus on these areas but also attend to other key factors, such as men’s health, environment, and social support, are needed to reduce the multiple risks for recidivism that men face.49 A strengths-based prevention framework that helps men maintain their health, monitor health risks, and seek treatment of acute conditions is necessary to target multilevel challenges and support holistic well-being.27,49

THE COMMUNITY REENTRY INITIATIVE

The Connecticut Building Bridges Community Reentry Initiative (CRI) was developed in response to the Connecticut General Assembly's 2004 Public Act Concerning Prison Overcrowding.50 The act mandated the development and implementation of a comprehensive reentry strategy to reduce recidivism and increase successful reentry through a network of community services, such as treatment, vocational counseling, education, and supervision, thereby reducing the $34 000 annual cost per individual of incarceration.51 Local legislators, policy analysts, social service providers, and community advocates began to develop pilot programs in 2005 for men returning to the largest urban areas in Connecticut, because these communities have the highest proportion of incarcerated individuals in the state.

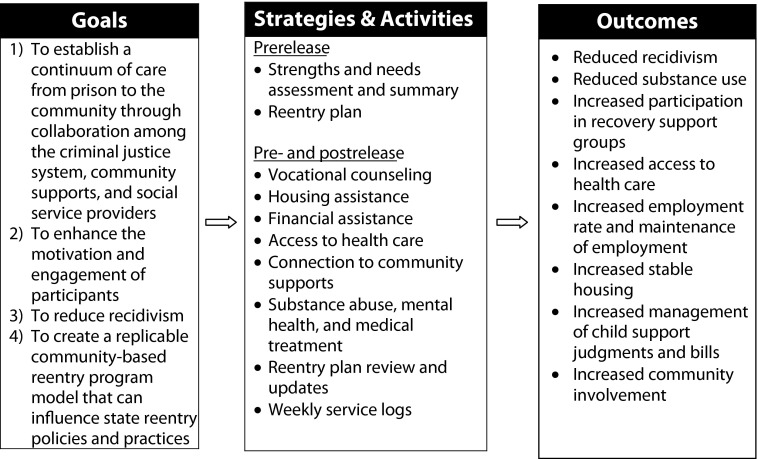

The CRI was designed to be consistent with best-practice literature,26,48,50,52 serving as a bridge between prison and the community. The program was guided by a strengths-based case management and intervention model,53 focusing on stable employment and housing, access to health care, community supports, formal supports (e.g., entitlements), and substance abuse and mental health treatment and aftercare. As shown in Figure 1, the CRI pilot program aimed to establish a continuum of care from prison to the community and to reduce recidivism rates. The $500 000 program was designed to serve 150 men, with a per-individual cost of approximately $3300.

FIGURE 1—

Conceptual model of the Connecticut Building Bridges Community Reentry Initiative, 2005–2007.

Men who participated in the CRI were expected to have lower recidivism and substance use rates as well as greater access to health care, stable employment and housing, fiscal responsibility, participation in substance abuse treatment, and involvement in community support programs than did men who received transitional supports through the usual mechanisms provided through the State of Connecticut Department of Correction (DOC).54 (Prior to release, DOC staff complete discharge plans with inmates and arrange linkages to community release programs, relapse prevention programs, medical treatment, and other community services, according to inmates’ needs. In addition to community supervision, the DOC funds community programs to support individuals after release, such as halfway houses, supportive housing for mental health and substance abuse difficulties, and employment assistance.)

Program Features

The CRI was piloted in 2 level 2 minimum-security correctional facilities in Connecticut with a combined population of 1600 inmates. The facilities focus on educational and addiction programming; inmates with significant physical or mental health needs are transferred to other facilities.52 To be eligible for the CRI and the evaluation, men had to be aged 18 years or older, within 3 to 6 months of release from prison, and willing and able to provide written consent to participate. Prior to release, each client who agreed to enroll in the CRI was assigned to a case manager, who completed a reentry plan with the client, provided support services, and coordinated care with other community service providers. Clients were expected to be centrally involved in the process of setting goals and planning for their reintegration into the community. Prior to and after release, case managers provided or arranged vocational counseling, assisted with housing and finances, facilitated access to health care, connected men to community supports, and coordinated substance abuse treatment, which are all consistent with universal and selective preventive interventions. Leveraging community and informal (natural) supports is a key factor in providing culturally competent services.46 Case managers also coordinated mental health and medical treatment in the community, which is consistent with indicated interventions. Case managers reviewed and updated the reentry plans every 60 days. To monitor progress, case managers completed weekly service logs for each client (Figure 1). Clients could stay in the CRI for up to 3 years; research suggests that individuals are at greatest risk of recidivism within 3 years of release.2

Evaluation Methods

We used a longitudinal, quasi-experimental evaluation design to determine the effectiveness of the CRI. The staff members at 1 of the participating correctional facilities determined eligibility and ascertained inmates’ interest in being part of the CRI. A demographically matched sample of inmates from the other facility, who would receive only the standard prerelease services provided through the DOC, was recruited as the comparison group. Individuals interested in participating in the intervention or in the comparison group for the evaluation completed the consent and release of health information procedures with a member of the evaluation team. Men were informed about their participation rights through informed consent forms, and participants’ information was protected from release under subpoena through a Department of Health and Human Services Certificate of Confidentiality. Participants were informed that the evaluation team would gather information to assist their case managers in treatment planning and to evaluate the program. We explained that declining to participate in the evaluation would not affect their services or status with the staff.

Following consent, the enrolled men completed an assessment that identified their strengths, needs, and goals for each target area for the intervention: education, employment, housing, financial resources, formal supports, informal supports, substance abuse, mental health, and physical health. An evaluation team member administered the assessments through semistructured interviews conducted during 3 distinct periods: before release (3 months prior to release), release (within 1 week of release), and after release (6-month intervals after release for up to 3 years or until clients’ discharge). We adapted the comprehensive assessment from the Criminal Justice–Drug Abuse Treatment Research Studies Intake Form,55 Transitional Case Management Strengths Inventory,56 Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale,57 Texas Christian University Drug Screen II,58 and psychological well-being scales.59 The DOC also provided health summaries to corroborate men’s self-reported mental and physical health information.

We used the assessment responses to generate a summary of each client's strengths, needs, and goals. Case managers used the strengths and needs summary to develop a reentry plan in collaboration with each client within 1 month of the prerelease intake. The reentry plans comprised a summary of the clients’ strengths and needs, goals and objectives, key prevention activities, and target problem resolution dates. We conducted multivariate analyses of data from the strengths and needs assessments, DOC health summaries, and service logs as well as content analyses of the reentry plans to examine men’s strengths, needs, and interventions that were consistent with universal, selective, and indicated risk factors.

Participants

The preliminary evaluation of the CRI was based on data for the 173 clients who were enrolled during the first 18 months of the program, between 2005 and 2007. More than two thirds (68.20%; n = 118) of the clients were African American, 24.86% (n = 43) were Latino, 4.05% (n = 7) were White, 0.58% (n = 1) were Asian American, and 2.31% (n = 4) self-identified as other. The high proportion of African American and Latino men is reflective of the incarcerated population as a whole. The men ranged in age from 19 to 54 years, with a mean age of 32.23 years (SD = 8.01). We used the Level of Service Inventory–Revised risk factors60 to classify the majority of clients (64.74%; n = 112) as at moderate risk for reoffending. Case managers reported spending up to 120 minutes per week with clients, with a mean meeting time of about 35 minutes. The number of contacts per week ranged from 1 to 5.

GOAL ATTAINMENT

All aspects of the men’s strengths and needs had health implications, which are presented in Table 1. Universal constructs measured were employment, housing status, informal supports, and access to health care. Among clients’ strengths were that most were employed and had stable housing prior to incarceration. Most men also reported having social and family supports. By contrast, many men reported barriers to reentry such as lack of medical insurance and inadequate community supports. Many of the men also were uncertain of their housing arrangements after release.

TABLE 1—

Clients’ Strengths and Needs: Connecticut Building Bridges Community Reentry Initiative, 2005–2007

| Assessment or DOC Health Summary Item | No. (%) |

| Universal risks a | |

| Employed prior to incarcerationb | 102 (58.96) |

| Housing | |

| Lived in own residence or with family prior to incarcerationb | 151 (87.28) |

| No permanent housing arrangements after releasec | 52 (30.06) |

| Access to health care | |

| Uninsured prior to incarcerationc | 78 (45.09) |

| No HIV test in past yc | 74 (42.77) |

| No physical, eye, or dental exam in past yc | 40 (23.12) |

| Informal supports | |

| Social and family supportsa | 138 (79.77) |

| Inadequate community resourcesc | 70 (40.46) |

| Feeling of isolationc | 55 (31.79) |

| Selective risks d | |

| Education | |

| Enrollment in postsecondary education programb | 151 (87.28) |

| Educational attainment of high school or equivalentb | 114 (65.90) |

| Participation in vocational/technical training in prisonb | 59 (34.10) |

| Financial stability | |

| Debtsc | 126 (72.83) |

| Received government assistance prior to incarcerationc | 123 (71.10) |

| Child support arrearagesc | 42 (24.28) |

| Substance abuse | |

| Substance abuse treatment in lifetimea | 107e (86.99) |

| Regular substance usec | 123 (71.10) |

| History of drug abuse or dependencec | 107 (62.00) |

| Tobacco usec | 104 (60.00) |

| Diagnosis of substance abusec,61 | 100 (58.00) |

| Substance abuse treatment in prisonb | 55 (44.72) |

| History of alcohol abuse or dependencec | 66 (38.00) |

| History of polysubstance abuse or dependencec | 42 (24.00) |

| Indicated risks f | |

| Mental health | |

| Good to excellent mental healthb | 153 (88.44) |

| Psychiatric disorders,c total | (< 25.00) |

| Anxiety | 40 (23.12) |

| Paranoia | 29 (16.76) |

| Depression | 28 (16.18) |

| Suicidal ideation or attempts | 10 (5.78) |

| Substance-induced delirium, hallucinations, or mood disordersc | 31 (18) |

| Physical health | |

| Good to excellent physical healthb | 153 (88.44) |

| Current prescription medicationsc | 27 (15.61) |

| Chronic health conditions,c total | (< 10) |

| Asthma | 17 (9.83) |

| High blood pressure | 15 (8.67) |

| Arthritis | 11 (6.36) |

| Diabetes | 4 (2.31) |

| Heart disease | 2 (1.16) |

| Sexually transmitted infectionsc | 6g (3.47) |

Note. DOC = Department of Correction. Health conditions and substance use were self-reported. The sample size was n = 173.

Applies to entire population of interest.

Strength.

Need.

Applies to a subgroup of the population that is at increased risk of difficulties.

Based on 123 men with substance abuse histories.

Applies to those at greatest risk.

No clients reported being HIV positive.

In reentry plans related to universal interventions, case managers used multiple strategies to facilitate housing and employment as well as to strengthen men’s connection to the community. They helped clients apply for housing funds, arranged temporary housing, met with vocational counselors, and referred clients to job training. Case managers connected clients to community supports, such as mentors, peers who had successfully reintegrated, family mediators to assist with restoration of family relationships, and community members to reinforce to men their value as citizens in their communities. To facilitate access to health care, managers helped clients apply for medical insurance entitlements.

Selective risks were histories of substance abuse or dependence and treatment, returning to unhealthy environments, inadequate educational attainment, and financial needs. The modal age of initiation of alcohol or illicit drug use was 16 years. The majority of men reported regular substance use (i.e., ≥ 1–5 times/week) prior to incarceration; participation in substance abuse treatment programs was a strength. Most men had at least a high school equivalent education; more than one third had participated in vocational training during incarceration. Most men also reported having significant debt and receiving government assistance in the past. The aspects of reentry plans that case managers developed related to selective interventions included arranging placement in sober houses, enrolling clients in zero-tolerance programs, connecting clients with self-help groups, helping clients enroll in adult education programs, and helping them apply for financial aid and open checking and savings accounts.

Indicated risks were mental illness, poor physical health, and chronic health conditions. Fewer than 25% of clients reported a history of psychiatric disorders or chronic physical health conditions. The DOC health summaries generally were consistent with the men’s self-reports, with few men receiving mental health diagnoses other than substance use disorders or diagnoses of chronic physical health conditions. The strategies that case managers developed with clients related to indicated interventions included arranging outpatient treatment, helping clients adhere to medication regimens, and scheduling physical exams.

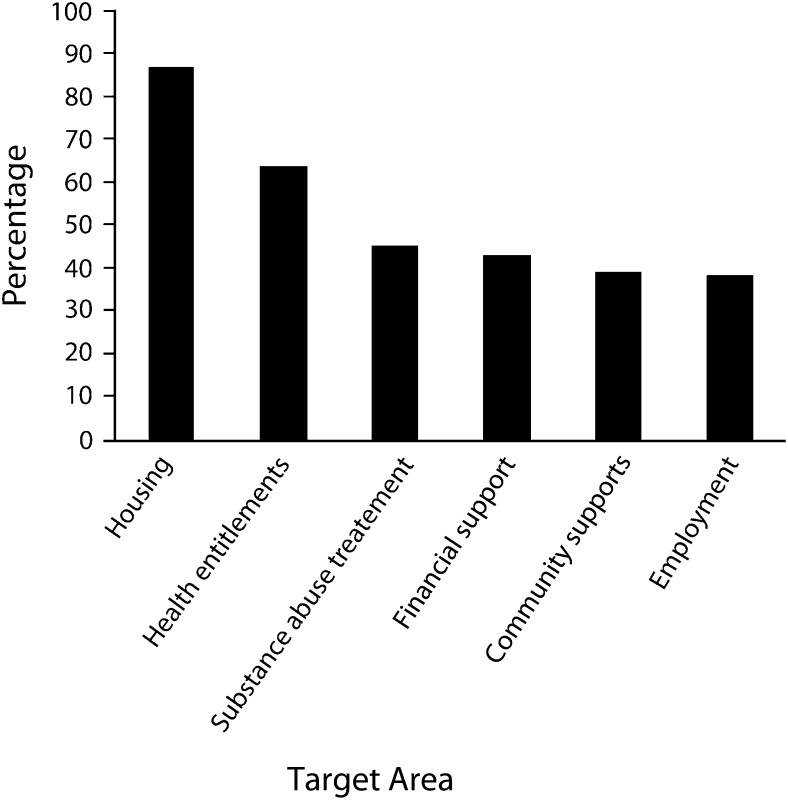

We examined the postrelease service log data for the 126 clients who had been released from prison by the time of the evaluation to assess preliminary intervention outcomes. Case managers reported that most men transitioned into halfway houses or private residences after release and received assistance with obtaining medical insurance. Nearly one half of the men with reported substance abuse histories received substance abuse treatment through a halfway or sober house or in outpatient or inpatient programs. More than one third of the clients secured employment, received financial support (e.g., vouchers), and received informal supports through community support and mentorship programs. Figure 2 presents the percentage of clients who achieved goals in each target area.

FIGURE 2—

Percentage of clients who met program goals (n = 126): Connecticut Building Bridges Community Reentry Initiative, 2005–2007.

COMMUNITY REINTEGRATION

We reviewed service log data to examine CRI participants’ reintegration into the community. At the end of the first 18 months of the CRI, approximately 65% (n = 82) of the clients who were released remained actively involved in the CRI, and 35% (n = 44) were discharged. Reasons for discharge included noncompliance, loss of contact, and request for withdrawal. Approximately 16% (n = 20) of the men recidivated, as defined by rearrest and reincarceration. (The total number of recidivated clients was greater than the number of clients who were discharged from the CRI because of recidivism. Clients with sentences of less than 1 year continued to be served, and some clients who were reincarcerated were discharged for other reasons, such as a request to withdraw.) The median time to recidivism was 90 days, and all of the 20 clients recidivated within 235 days of release.

We examined the relationship between the multilevel interventions and men’s successful reentry (i.e., engagement in the CRI and low risk of recidivism) by binary logistic regression. Clients who obtained employment after release were less likely to become inactive or withdraw from the program than were clients who remained unemployed (odds ratio [OR] = 0.31; P < .05). Employment within 30 days of release did not affect engagement. Clients who lived with family members or in their own residence after release were more likely to become inactive or withdraw from the program than were men who lived in transitional housing (OR = 3.12; P < .05). Clients who participated in community support programs (i.e., mentorship, peer support, family, mediation, community member conversations) were less likely to recidivate than were those who did not receive such supports (OR = 0.28; P < .05). Increasing access to health care by assisting clients with obtaining medical insurance did not significantly affect engagement or recidivism. With respect to the subset of clients who needed financial supports, assistance with financial and child support needs did not significantly affect engagement or recidivism. For the subset of clients with substance abuse histories, those who received substance abuse treatment were less likely to become inactive or withdraw than were those who did not receive treatment (OR = 0.22; P = .01). Men who were connected with treatment services outside of those provided through halfway and sober houses were particularly likely to remain engaged (OR = 0.07; P = .05). Participation in substance abuse treatment was not significantly related to recidivism. Table 2 displays the regression results for each level of intervention.

TABLE 2—

Binary Logistic Regression of Client Engagement and Recidivism on Universal, Selective, and Indicated Interventions: Connecticut Building Bridges Community Reentry Initiative, 2005–2007

| Poor Engagement |

Recidivism |

|||

| Intervention Variable | OR (95% CI) | B or −2 Log Likelihood (χ2) | OR (95% CI) | B or −2 Log Likelihood (χ2) |

| Universal (n = 110) | 108.06* (12.24) | 96.74 (7.57) | ||

| Employment | 0.31* (0.11, 0.89) | −1.16 | 1.74 (0.62, 4.94) | 0.55 |

| Private residence (independent or with family) | 3.12* (1.20, 8.11) | 1.14 | 0.60 (0.21, 1.76) | -0.51 |

| Community supports | 1.15 (0.43, 3.08) | 0.14 | 0.26* (0.08, 0.88) | −1.35 |

| Access to health care | 0.47 (0.18, 1.26) | -0.75 | 1.03 (0.36, 2.95) | 0.03 |

| Selective (n = 94) | 97.76 (4.54) | 70.50 (1.30) | ||

| Financial assistance | 0.89 (0.32, 2.51) | -0.12 | 1.44 (0.42, 5.00) | 0.36 |

| Child support arrangements | 0.00 | −20.13 | 2.51 (0.44, 14.23) | 0.92 |

| Indicated (n = 100) | 103.50** (8.97) | 97.19 (0.05) | ||

| Any substance abuse treatment | 0.22** (0.07, 64) | −1.52 | 1.13 (0.41, 3.06) | 0.12 |

| Nontransitional housing treatment | 0.07* (0.01, 0.54) | −2.68 | 1.28 (0.41, 3.98) | 0.25 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Universal preventive interventions are directed at the entire population of interest, selective interventions are for a subgroup of the population that is at increased risk of difficulties, and indicated interventions are designed for those at greatest risk.

*P < .05; **P < .01.

PROGRAM STRENGTHS AND CLIENT ENGAGEMENT

The observations from a preliminary evaluation of the CRI suggest a continued need to target all identified risk factors of individuals reentering the community from prison to support their physical, mental, and emotional health. Men in the CRI reported the greatest strengths in the areas of housing, social supports, education, and quality of health. They reported the greatest need in the areas of substance use, health insurance, preventive health care, finances, and community resources. The majority of men met their goals related to health insurance; most did not meet their goals in their other areas of greatest need. Case managers reported using multiple strategies to address areas such as substance use, housing, and employment. However, they developed fewer strategies for areas more related to prevention than to treatment or immediate needs. Case managers reported limited plans for health promotion (e.g., medical homes, health education), which are critical to ensuring men’s health and reintegration after release.

Consistent with extant reentry initiative evaluation literature,29,47,48 assistance with employment and substance abuse treatment positively affected engagement in the program, and community support was protective against recidivism. Substance abuse treatment outside of transitional housing was particularly effective, possibly because men who sought such programs were more motivated than were men participating in treatment that was part of existing structured programs. By contrast to the literature, living in private residences was related to decreased engagement in the program. Men with such stability might not have recognized the importance of multiple supports, seeing their families or themselves as sufficient rather than taking advantage of the additional resources and support that the CRI could provide.40 The findings underscore the importance of employment, substance abuse treatment, and informal supports in successful reintegration into the community but also reveal the necessity of understanding clients’ perception of their recidivism risk. Service providers should help educate clients about the various risks to recidivism beyond basic needs, which many clients recognize. Particularly for men with substance abuse histories, it also is important to help them understand triggers for past behaviors that increase the risk of relapse, consequences of use, and poor engagement in reentry services.15

HEALTH NEEDS

In part because of the type of correctional facilities in which the CRI was piloted, men in the program reported few acute health conditions. Their health status affords an opportunity to further promote their health and that of their communities. Often, addressing health in prison is a more indicated realm, with staff providing treatment to acute conditions; however, focus must be more on prevention to best serve all individuals returning to the community from prison. To increase men’s capacity to stay healthy, it is essential to educate them on increased health risks attributable to incarceration, to educate them on ways that they can self-manage health, and to emphasize the importance of receiving regular health care in the community. Ensuring access to health care is a good first step, but individuals returning to the community need to take advantage of health care services. To prevent relapse and reduce the risk of developing significant health concerns, it is necessary for these men to understand their risks related to substance abuse, mental health, and physical health and to continue any treatment or care they received in prison. It is important to provide consultation to clients about potential health challenges, preventive care, and health-promoting behaviors to reduce the likelihood that they will seek care only for urgent or chronic health issues. Helping formerly incarcerated men become proactive about their health is especially important in light of racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care30 as well as gender-related issues regarding health, such as masculinity, shame, and guilt.38–40

The CRI model began to fill the gap in ensuring the health of individuals returning to the community from prison, but more work is needed to support men’s health and expand the definition of continuum of care. At the time of the preliminary evaluation, the comparison group sample was too small to use as a comparison for the CRI clients. In addition, a selection bias may have operated: men who were most motivated to reintegrate may have agreed to participate in the CRI. We did not have access to data on the individuals who did not consent to enroll and therefore could not test for significant differences between men who did and did not enroll. Another limitation of the evaluation was that self-reported information was a primary source of data. Although the DOC health summaries augmented the self-reported data, they did not address all of the universal, selective, and indicated health risks that could have been present for the sample. Future research should continue to examine multilevel health risks, interventions, and outcomes for formerly incarcerated individuals.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our evaluation showed that case managers and providers appeared to have the capacity to address employment, education, and housing, as suggested by the variety of planned interventions and strategies in these areas. Case managers reported fewer strategies for helping men use preventive health services, which all men need. Specific recommendations to ensure continuity of care and support after release to facilitate successful reentry are as follows:

Use the prevention science framework for education, planning, and service delivery. Case managers can work collaboratively with clients to develop reentry action plans that identify needs at each level of risk, plan strategies that build on their strengths and resources to reduce these risks, and revisit the plans to track progress. Case managers can use the framework to educate clients on health implications for each level of risk and the multiple systems in which they will be a part (e.g., workforce, community, family) when they return to the community.

Build case managers’ capacity to help individuals understand the social determinants of health and identify all types of needs that increase risk of recidivism to ensure that areas that typically receive more focus (e.g., employment, housing) and those that also are important but might be considered less in planning (e.g., preventive care, informal supports) are adequately addressed. Increase providers’ capacity to leverage informal supports and other resources to help men achieve their goals, reduce risks, and increase health equity by continuing to develop cultural competency to serve African American, Latino, and other overrepresented—and historically underserved—prisoner and former prisoner populations.

Work with individuals to recognize environmental triggers (e.g., previous neighborhoods, friends, family members) that might threaten their engagement and success. Determine the level of outreach required to engage individuals and encourage consistent, active participation.

CONCLUSIONS

The impact of incarceration is not confined to the prison walls.7,11,16,32 Changes in sentencing and release policies have substantially increased the number of individuals—especially African American and Latino men—in the correctional system and the number who are released back to the community. Threats to successful community reintegration include lack of adequate housing, community and social supports, education, and employment; physical and mental health concerns; and substance abuse. A lack of resources and opportunities often contributes to incarceration and to difficulties after release. Rather than simply looking at overall program effects of interventions, allowing some nuances to be lost, it is essential to consider individuals’ universal, selective, and indicated risks to successful reentry to best tailor pre- and postrelease supports.

The prevention framework can help providers and men returning to the community conceptualize and recognize multiple risks and proactively develop a comprehensive plan not only to address immediate needs but also to put supports in place to prevent potential difficulties. By identifying the degree to which universal, selective, and indicated risks are addressed in planning and by aligning identified strengths and needs with strategies outlined in reentry plans, case managers can identify gaps in services and determine how to better connect men to needed resources. Furthermore, understanding the relationship between participation in strategies to address risk and successful reentry can reveal the importance of areas (e.g., community support) that might not be focused on when higher risks (e.g., substance abuse) alone are considered.

To improve continuity of care after release from prison, it is important to consider the role of prevention in reentry planning for all individuals—not just those with highest risk—and to examine complexities at each level of risk that have implications for health. Service providers should increasingly explore holistic health needs and facilitate pre- and postrelease continuity of care. Leveraging resources through the corrections and judicial systems is one way to ensure that reentry preparation begins in prison. Service providers should continue to encourage clients’ consistent, active participation and develop strategies to critically examine whether they are achieving their stated goals for reentry. Moving forward, it is imperative to understand the complexity of the key risks to reentry and how ensuring continuity of care and supports for individuals rejoining the community after incarceration can facilitate their healthy and permanent return.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided in part by Connecticut’s Court Support Services Division, Judicial Branch; Family Reentry, Bridgeport, CT; and Connecticut’s Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Article preparation for LaKeesha N. Woods was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Drug Abuse (T32 DA019426-01). Community Science provided support for editing of the article.

Note. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed in this article are the authors' and do not necessarily reflect the views of Connecticut’s Court Support Services Division, Judicial Branch; Family Reentry, Bridgeport, CT; Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services; or the National Institutes of Health.

Human Participant Protection

The Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee approved the study.

References

- 1.Legislative Program Review and Investigations Committee Recidivism in Connecticut. Hartford, CT: Connecticut General Assembly; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes T, Wilson DJ. Reentry trends in the United States. Available at: http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pub/pdf/reentry.pdf. Accessed February 25, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Justice Serious and violent offender reentry initiative. Available at: http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/reentry.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson DB, Schumacker RE, Anderson SL. Releasee characteristics and parole success. J Offender Rehabil. 1991;17(1–2):133–145 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewster DR, Sharp SF. Educational programs and recidivism in Oklahoma: another look. Prison J. 2002;82(3):314–334 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golembeski C, Fullilove R. Criminal (in)justice in the city and its associated health consequences. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1701–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massoglia M. Incarceration as exposure: the prison, infectious disease, and other stress-related illnesses. J Health Soc Behav. 2008;49(1):56–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnittker J, John A. Enduring stigma: the long-term effects of incarceration on health. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(2):115–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas JC, Torrone E. Incarceration as forced migration: effects on selected community health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1762–1765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willmott D, van Olphen J. Challenging the health impacts of incarceration: the role for community health workers. Californian J Health Promot. 2005;3(2):38–48 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaiter JL, Potter RH, O’Leary A. Disproportionate rates of incarceration contribute to health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1148–1149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.London AS, Myers NA. Race, incarceration, and health: a life-course approach. Res Aging. 2006;28(3):409–422 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freudenberg N. Jails, prisons, and the health of urban populations: a review of the impact of the correctional system on community health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(2):214–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Rep. 2002;117(suppl 1):S135–S145 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Travis J, Cincotta McBride E, Solomon AL. Families Left Behind: The Hidden Costs of Incarceration and Reentry. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Boyd Wet al. The health and health care of US prisoners: results of a nationwide survey. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):666–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sexual Violence Prevention: Beginning the Dialogue. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiss D, Price RH. National research agenda for prevention research: the National Institute of Mental Health Report. Am Psychol. 1996;51(11):1109–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bronfenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kellam SG, Langevin DJ. A framework for understanding “evidence” in prevention research and programs. Prev Sci. 2003;4(3):137–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tebes JK, Kaufman JS, Connell CM. The evaluation of prevention and health promotion programs. In: Gullotta TP, Bloom M, eds. Encyclopedia of Primary Prevention and Health Promotion. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003:42–61 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hairston CF. The forgotten parent: understanding the forces that influence incarcerated fathers’ relationships with their children. Child Welfare. 1998;77(5):617–639 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King AE. The impact of incarceration on African American families: implications for practice. Fam Soc. 1993;74(3):145–153 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clear TR, Rose DR, Ryder JA. Incarceration and the community: the problem of removing and returning offenders. Crime Delinq. 2001;47(3):335–351 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holzer HJ, Offner P, Sorensen E. Declining employment among young Black less-educated men: the role of incarceration and child support. Madison, WI: Institute for Research on Poverty; 2004. Discussion Paper no. 1281-04. Available at: http://www.irp.wisc.edu/publications/dps/pdfs/dp128104.pdf. Accessed November 30, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travis J, Petersilia J. Reentry reconsidered: a new look at an old question. Crime Delinq. 2001;47(3):291–313 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seiter RP, Kadela KR. Prisoner reentry: what works, what does not, and what is promising. Crime Delinq. 2003;49(3):360–388 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brennan Ramirez LK, Baker EA, Metzler M. Promoting Health Equity: A Resource to Help Communities Address Social Determinants of Health. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrison LD. The revolving prison door for drug-involved offenders: challenges and opportunities. Crime Delinq. 2001;47(3):462–485 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersilia J. Prisoner reentry: public safety and reintegration challenges. Prison J. 2001;81(3):360–375 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on drug use and health, 2006 and 2007. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k7NSDUH/tabs/Sect5peTabs1to56.htm#Tab5.8B. Accessed May 24, 2012 [PubMed]

- 32.McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC. Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):840–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Tien HC, Stewart P, Kaplan AH. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(1):84–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lurigio AJ. Effective services for parolees with mental illness. Crime Delinq. 2001;47(3):446–461 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kupers TA. Trauma and its sequelae in male prisoners: effects of confinement, overcrowding, and diminished services. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66(2):189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Massoglia M. Incarceration, health, and racial disparities in health. Law Soc Rev. 2008;42(2):275–306 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am Psychol. 2003;58(1):5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(10):1385–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Efthim PW, Kenny ME, Mahalik JR. Gender role stress in relation to shame, guilt, and externalization. J Couns Devel. 2001;79(4):430–438 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iwamoto DK, Gordon DM, Oliveros Aet al. The role of masculine norms and informal support on mental health in incarcerated men. Psychol Men Mascul. 2012;13(3):283–293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hammett TM, Gaiter JL, Crawford C. Reaching seriously at-risk populations: health interventions in criminal justice settings. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(1):99–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Report of the Re-entry Policy Council. New York, NY: Council of State Governments; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Austin J. Building Bridges: From Conviction to Employment: A Proposal to Reinvest Corrections Savings in an Employment Initiative. New York, NY: Council of State Governments Criminal Justice Programs; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivera ET, Wilbur MP, Roberts J. The Puerto Rican prison experience: a multicultural understanding of values, beliefs, and attitudes. J Addict Offender Couns. 1998;18(2):63–74 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Summary of new health reform law. Available at: http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/8061.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Betancourt JR. Improving Quality and Achieving Equity: The Role of Cultural Competence in Reducing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inciardi JA, Martin SS, Butzin CA. Five-year outcomes of therapeutic community treatment of drug-involved offenders after release from prison. Crime Delinq. 2004;50(1):88–107 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Open Society Institute Groundbreaking study identifies crucial factors for successful community reintegration of ex-prisoners in Baltimore. Available at: http://www.soros.org/initiatives/baltimore/press/groundbreaking_20040315. Accessed February 25, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bobbitt M, Nelson M. The Front Line: Building Programs That Recognize Families’ Role in Reentry. New York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 50.January 14, 2006. Connecticut General Assembly. Public Act No. 04–234 An Act Concerning Prison Overcrowding. Available-at: http://www.cga.ct.gov/2004/ act/Pa/2004PA-00234-R00HB-05211-PA.htm. Accessed.

- 51.State of Connecticut Department of Correction. August 13, 2010 Available at: http://www.ct.gov/doc. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klein SR, Bartholomew GS, Bahr SJ. Family education for adults in correctional settings: a conceptual framework. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminal. 1999;43(3):291–307 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rapp CA, Wintersteen R. The strengths model of case management: results from twelve demonstrations. Psychosoc Rehabil J. 1989;13(1):23–32 [Google Scholar]

- 54.State of Connecticut Department of Correction Offender management plan: corrections to the community. Available at: http://www.ct.gov/doc/lib/doc/pdf/offendermanagementplan.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies CJ-DATS Form 464. Available at: http://cjdats.org/content_documents/3-64%20CJ%20DATS%20Intake%20august20051.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Criminal Justice Drug Abuse Treatment Studies Transitional case management strengths inventory. Available at: http://www.uclapcrc.org/partners/TCM/html/tcm-instruments.html. Accessed August 16, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 58.TCU Drug Screen II. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Institute of Behavioral Research; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bradburn NM. The structure of psychological well-being. Available at: http://cloud9.norc.uchicago.edu/dlib/spwb/index.htm. Accessed August 16, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andrews D, Bonta J. Level of Service Inventory–Revised. Cheektowaga, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994 [Google Scholar]