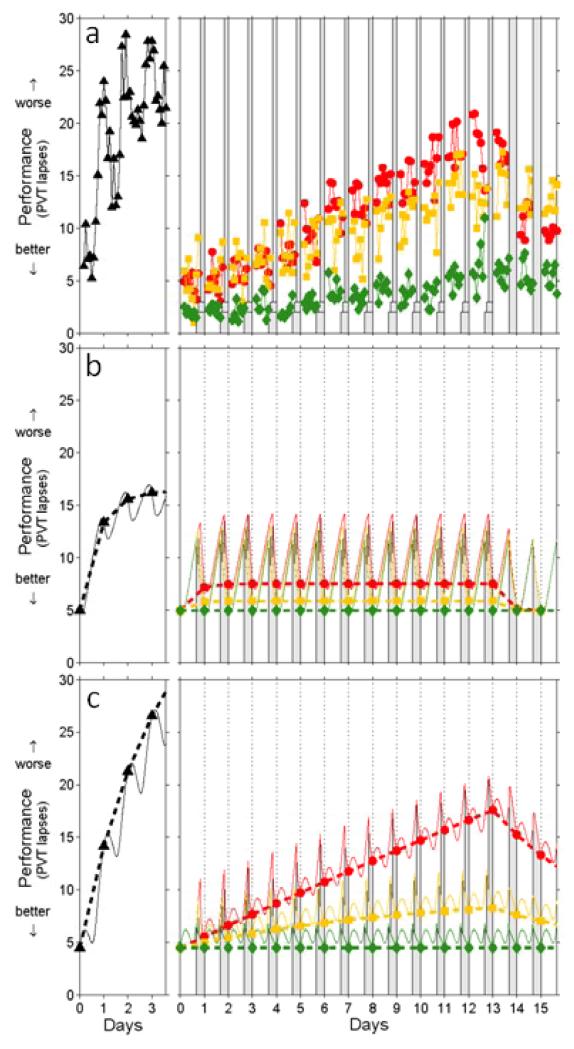

Figure 1.

Neurobehavioral performance observations and predictions by different models. A total of 48 healthy young adults were subjected to one of four laboratory sleep deprivation protocols [12]. Each protocol began with several baseline days involving 16 h scheduled wake time (SWT)/8 h time in bed (TIB); the last of these baseline days is labeled here as day 0. Subsequently, 13 subjects were kept awake (24 h SWT/0 h TIB) for three additional days, for a total of 88 h awake (left panels), after which they received varied amounts of recovery sleep (not shown). The other subjects underwent various doses of sleep restriction for 14 consecutive days, followed by two recovery days with 16 h SWT/8 h TIB (right panels). The sleep restriction schedule involved 20 h SWT/4 h TIB per day for 13 subjects (circles; red); 18 h SWT/6 h TIB per day for another 13 subjects (boxes; yellow); and 16 h SWT/8 h TIB per day for the remaining nine subjects (diamonds; green). Awakening was scheduled at 07:30 each day. Neurobehavioral performance was tested every 2 h during scheduled wakefulness using the PVT, for which the number of lapses (reaction times greater than 500 ms) was recorded. (a) Observed neurobehavioral performance (PVT lapses) for each test bout (dots represent group averages). The first two test bouts of each waking period are omitted in order to avoid confounds from sleep inertia. Gray bars indicate scheduled sleep periods. (b) Corresponding performance predictions according to the two-process model [34], linearly scaled to the data. Data points represent performance predictions at wake onset. Thin curves represent predictions within days, but the focus here is on changes across days (dashed lines). Note the rapid stabilization across days predicted to occur in the chronic sleep restriction conditions (right panel), which does not match the observations shown in (a). (c) Corresponding predictions according to the model introduced by McCauley et al. [42] as defined by their Eqs. (21) and (26). Note the improved fit to the experimental observations across days for total sleep deprivation (left panel), as well as for the 20 h SWT/4 h TIB condition (right panel). Performance impairment in the 18 h SWT/6 h TIB and 16 h SWT/8 h TIB conditions (right panel) is under-predicted. However, the group-average impairment levels observed for these conditions are inflated due to a few outliers [12]. (Figure and caption modified based on J Theor Biol 256 (2009), 227-239, McCauley P, Kalachev LV, Smith AD, Belenky G, Dinges DF, Van Dongen HPV, A new mathematical model for the homeostatic effects of sleep loss on neurobehavioral performance, Copyright 2009, with permission from Elsevier).