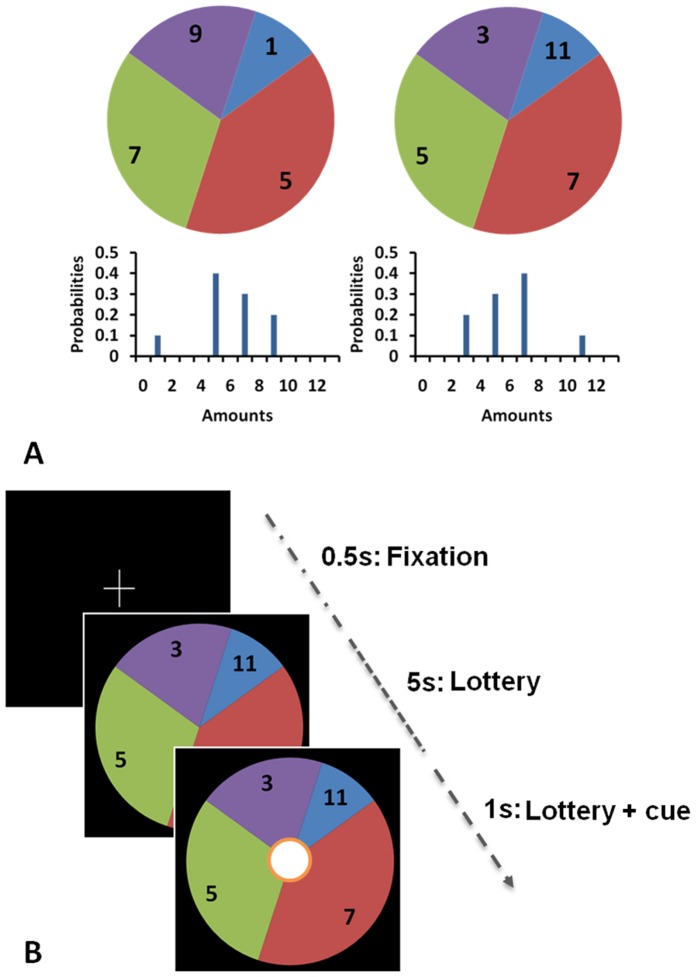

Figure 1. Experimental Paradigm.

A. We represented gambles on-screen as pie-charts. The pie chart was divided into different segments showing possible outcomes from the lottery. The numbers written in each segment showed the monetary value of each outcome (in pounds sterling) and the angle subtended by each segment indicated the probability of each outcome occurring. A negatively skewed gamble (left) has a small chance of a worse than average outcome (the tail of the distribution is to the left). Conversely, a positively skewed gamble (right) has a small chance of a better than average outcome (the tail is to the right). Both example gambles have identical expected value (£6) variance (5£2), but opposite skewness (+/−7.2£3). B. Each task consisted of 252 trials. For each trial, a pie chart was shown, and after 5 seconds, a cue to respond appeared on screen (for 1 second). Subjects indicated by a button press while the cue was on-screen if they wanted to gamble on the lottery, or alternatively select a fixed, sure amount of money (of £4.50 throughout). At the end of the experiment on their second visit, four trials were randomly selected and played out for real. If subjects had elected to gamble, we resolved the lottery by an on-screen graphic of a red ball spinning around the outside of the pie which stopped at a randomly selected position.