Abstract

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare but potentially fatal disorder resulting from a highly stimulated immune response with uncontrolled accumulation of lymphocytes and macrophages in multiple organs. Both the inherited and acquired forms of this disease exist; the latter can sometimes occur secondary to different malignancies. In this report, we present a middle-aged Hispanic man who presented with features of septic shock during the course of chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the neck. Despite aggressive treatment for septic shock, he rapidly deteriorated and died after 30 h of admission. Autopsy findings confirmed a diagnosis of HLH. HLH should be recognised as a serious adverse event during chemotherapy for different malignancies including squamous cell carcinoma of the neck.

Background

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening condition characterised by cytokine dysfunction leading to the uncontrolled accumulation of activated T-lymphocytes and activated histiocytes (macrophages) in many organs. Cytotoxic cells and macrophages cause haemophagocytosis, severe systemic inflammation and multiorgan damage. It occurs in two distinct forms: an inherited form and an acquired form. The inherited, autosomal recessive form has been attributed to defects in peforin function and other cytolytic pathways.1 It usually occurs in the first year of life and is rapidly fatal unless treated.2 The acquired form (also known as the macrophage activation syndrome) can develop at any age, and is usually secondary to infections (mycobacterium, Ebstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus, HIV, herpes and protozoal infections), drug exposure (immunomodulatory drugs), autoimmune inflammatory diseases (eg, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Still's disease, etc) and malignancies (eg, leukaemia, lymphomas, multiple myeloma, hepatocellular carcinoma and germ cell tumours, etc).3 4

Acquired HLH usually presents with a rapidly progressive clinical course, although a chronic form has also been described.1 Clinical manifestations include fever, rash, weight loss, lymphadenopathy and organ enlargement. Laboratory tests reveal cytopenia, serum ferritin elevation, hypertriglyceridaemia and coagulation disorders.5 The reference standard for the diagnosis remains the presence in histological specimens of haemophagocytic macrophages in bone marrow, liver or lymph nodes, which may be lacking early in the disease leading to diagnostic challenges. Here, we report a case of a middle-aged Hispanic man who presented with features of refractory shock during the course of chemotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the neck. Despite aggressive treatment for suspected septic shock, the patient rapidly deteriorated and died within 30 h of the onset of shock. A diagnosis of HLH was confirmed at autopsy. Although HLH is a known complication of multiple haematological and some solid organ malignancies, to our knowledge it has not been previously reported to occur with squamous cell carcinoma.

Case presentation

A 56-year-old Hispanic man presented with fever, respiratory distress and lethargy for 2 days. The patient was recently diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of the neck and had received chemotherapy 1 week previously. His malignancy was found to be at an advanced stage (stage IV B), precluding surgical resection. He was scheduled to have four cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with docetaxel (TXT), cisplatin (CDDP) and 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu) (TPF regimen), followed by radiation therapy. He had received his first cycle of chemotherapy a week prior to his current presentation. His other medical conditions included coronary artery disease, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, hypothyroidism, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia. He denied intravenous drug abuse, a history of collagen vascular diseases, other malignancies and recent travel outside the country. His medications included hydralazine, furosemide, levothyroxine, lisinopril, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol, atorvastatin and amiodarone. Physical examination revealed an obese Hispanic man of stated age in moderate respiratory distress. Vital signs at presentation included a blood pressure of 87/56 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 27 breaths/min, pulse rate of 80 bpm, temperature of 38.7°C and oxygen saturation of 83% on room air. Neck examination was positive for a single, hard, non-tender level II right cervical lymph node. An abdominal exam revealed mild diffuse tenderness but absence of organomegaly, guarding, rigidity and rebound tenderness.

Investigations

The patient's complete blood count revealed pancytopenia (white blood cell count of 1 700/mm3, haemoglobin of 9.7 g/dL and platelet counts of 78 000/mm3). Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a severe anion gap metabolic acidosis due to lactic acidosis (pH 7.2, bicarbonate 8 mEq/L and lactic acid 13 mEq/L). Renal functions, liver functions and thyroid function tests were within normal limits. A non-contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed mild splenomegaly but was otherwise unremarkable. Blood, urine and sputum cultures were sterile. Serum cortisol levels did not demonstrate adrenal insufficiency.

Differential diagnosis

On the basis of fever, respiratory distress, hypotension, leucopenia and metabolic acidosis, we considered the possibility of septic shock secondary to chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression.

Treatment

The patient was aggressively resuscitated using Early Goal Directed Therapy and was started on broad spectrum empiric antibiotics (vancomycin, piperacillin and tazobactam). Despite these measures, he had a rapid decompensation in the next 6 h with altered sensorium and severe respiratory distress requiring endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

In the next 24 h, the patient rapidly deteriorated with shock refractory to intravenous fluids (normal saline and albumin) and multiple vasopressors (norepinephrine and vasopressin) and acute respiratory distress syndrome resulting in multiorgan failure. He subsequently died within 30 h of presentation. Laboratory results available after his demise revealed a negative serology for EBV, cytomegalovirus, human herpes virus 6, hepatitis B and C virus and HIV. Serum quantiferon assay was also negative. Blood, urine and sputum cultures were still sterile even after 72 h. His ferritin, triglyceride and fibrinogen levels were 9786 ng/mL, 524 mg/dL and 0.98 mg/L, respectively.

Outcome and follow-up

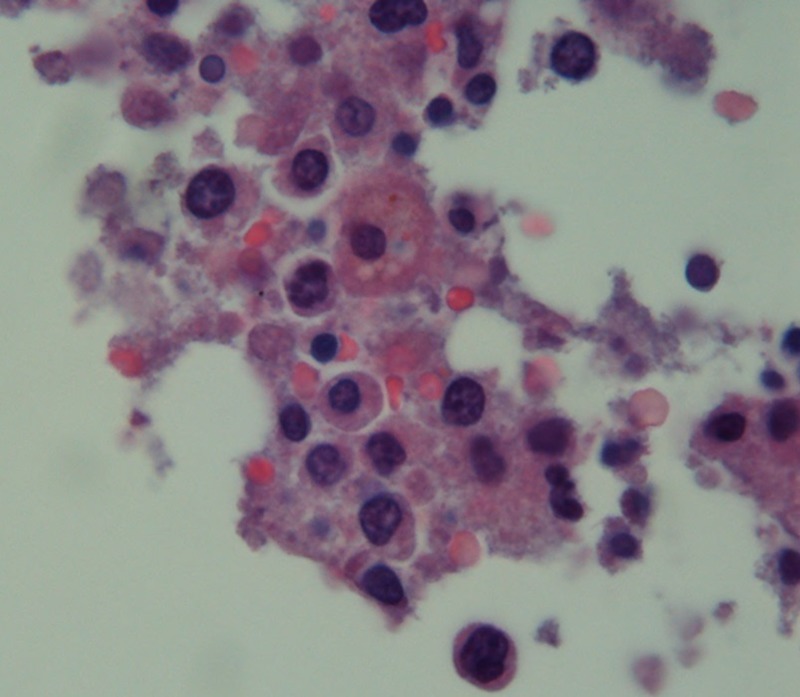

At autopsy, there were features suggestive of haemophagocytosis in the bone marrow (figure 1). Retrospectively, a diagnosis of refractory shock due to HLH was made. Level of CD 25 (also known as IL 2 soluble receptor) and natural killer (NK) cell activity could not be carried out since the patient had rapid deterioration in his clinical course.

Figure 1.

Bone marrow micrograph showing histiocytes with engulfed red blood cells.

Discussion

Malignancy-associated HLH (MHLH) can manifest before or during the treatment of a known malignancy, or sometimes even masking the signs and symptoms of malignancy.6 MHLH, in itself, is a rare entity with few published data available.1 2 6 7 In a recent population-based study, the annual incidence of MHLH was estimated to be 1/280 000 per year.8 Most cases of MHLH have been described in association with T cell, or NK cell lymphomas and leukaemias.9 Other malignancies reported to be associated with MHLH include multiple myeloma, renal cell carcinoma, neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, Ewing's sarcoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, melanoma, thymoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, lung and breast adenocarcinoma and non-seminomatous germ cell tumour.2 6 7 10 HLH associated with lymphomas has a considerably higher mortality rate compared to HLH due to infections and autoimmune disease.11

The pathophysiology of HLH involves lymphocyte hyperactivation (release of proinflammatory cytokines interferon γ, interleukins 18 and 6 and TNF-α) and hypergammaglobulinaemia. High levels of interleukin-1, interleukin-6, TNF and interferon γ cause fever, upregulation of ferritin transcription and secretion, and cytopenias through myelosuppression. There is also extensive phagocytosis of blood cells by macrophages in the bone marrow and the lymphoid organs after stimulation by a virus or another factor.12 The clinical and laboratory features of HLH are due to multiorgan infiltration and damage (affecting the bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes and central nervous system).13 14

Haemophagocytosis is often a late feature, and is not necessary for diagnosis of HLH. Other laboratory abnormalities may include a decrease in serum fibrinogen with or without disseminated intravascular coagulation, hypoalbuminaemia, hyponatraemia due to inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, β-2 microglobulin elevation in the blood and urine, serum lipase elevation and lactic acidosis.5 15 The soluble haemoglobin-haptoglobin scavenger receptor CD163 is a new and specific marker for macrophages for HLH disease activity. Its levels track closely with disease activity and correlate with serum ferritin.11 16 Ferritin level with a cut-off of 500 μg/L has a sensitivity of 84% and greater than 10 000μg/L has 90% sensitivity and 96% specificity.17 18

The following table is meant as a quick reference to help in the diagnosis of HLH. Either one of the two criteria should be fulfilled for the diagnosis.

Diagnostic guidelines for HLH (adapted from Histiocyte Society)

Molecular diagnosis consistent with HLH: pathologic mutations of PRF1, UNC13D, Munc18–2, Rab27a, STX11, SH2D1A or BIRC4; OR

- Diagnostic criteria for HLH fulfilled (5 out of 8 criteria below):

- Fever

- Splenomegaly

- Cytopenias affecting >1 line (haemoglobin<90 g/L, platelet count <100×109/L, polymorphonuclear cells <1.0×109/L)

- Fasting triglycerides >2.65 g/L or fibrinogen <1.5 g/L

- Hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes or liver

- Low or absent NK-cell activity

- Ferritin >500 μg/L

- Elevated soluble CD25 (also known as the soluble IL-2 receptor).

Our patient met the following six criteria for diagnosis: fever, pancytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, hyperferritinaemia, splenomegaly and hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow. He had respiratory distress, hypoxaemia, metabolic acidosis and pancytopenia, otherwise a classic picture of septic shock. We were easily misled to a diagnosis of septic shock in the background of fever with hypotension in the setting of recent chemotherapy and myelosuppression. Owing to the rarity of the condition, HLH was not taken into consideration in time. The clue was obtained only after the last set of blood tests which revealed significant ferritin elevation (performed for his anaemia) and hypertriglyceridaemia. Our patient developed features of HLH during the course of chemotherapy. An inherited form of HLH was less likely as it presents during childhood. In addition, other causes of secondary forms were less likely, given a negative viral panel and a negative history of rheumatological diseases. In this case, it is not clear if the HLH was triggered by malignancy itself or is related to chemotherapy. Some authors believe that chemotherapy-induced HLH is a separate entity apart from MHLH.2 9 12 19 We hypothesise that in our case HLH was triggered by an acute inflammatory event secondary to rapid tissue destruction during chemotherapy. Other possibilities include an undiagnosed occult infection triggering HLH, or an exceedingly rare adult onset type of familial HLH.

Survival from HLH requires prompt recognition and treatment; otherwise, death rapidly results from haemorrhage, multisystem organ failure or infection.2 In all cases, the underlying trigger must be aggressively sought and treated. Usual treatment consists of immunosuppressants, intravenous immunoglobulin and plasmapharesis. Intravenous etoposide (VP-16) is the chemotherapeutic agent of choice for treating HLH.20 The HLH-2004 protocol from the Histiocyte Society includes a very high dose of glucocorticoid therapy. Dexamethasone therapy is recommended in patients with predominant neurological manifestations as it crosses the blood–brain barrier compared with prednisone.5 21 Cyclosporine has been effective in a few patients with HLH due to some viral infections or autoinflammatory diseases but has a higher side effect of neurotoxicity (encephalitis and seizure). The monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab may be helpful when used in combination with etoposide in EBV-related HLH.4 Bone marrow transplant may be needed in refractory cases.3

In summary, HLH is a rare life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome that may occur secondary to a variety of malignancies including a squamous cell carcinoma. Any patient who deteriorates during anticancer therapy without an explainable cause should be considered for the possibility of HLH. Chemotherapy-related HLH could mimic chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression complicated with infection.

Learning points.

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome that may occur secondary to a variety of malignancies including a squamous cell carcinoma.

Any patient who deteriorates during anticancer therapy and presents with refractory shock without an explainable cause should be considered for the possibility of HLH.

Chemotherapy-related HLH could mimic chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression complicated with infection. It is important to differentiate between the two owing to the differences in management.

Footnotes

Contributors: MRA and SG wrote the initial draft and prepared the final draft of the case report. SA carried out the final revisions. MB obtained the pathological slide and revised the initial draft.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Maakaroun NR, Moanna A, Jacob JT, et al. Viral infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Rev Med Virol 2010;2013:93–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fardet L, Lambotte O, Meynard J-L, et al. Reactive haemophagocytic syndrome in 58 HIV-1-infected patients: clinical features, underlying diseases and prognosis. AIDS 2010;2013:1299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deane S, Selmi C, Teuber SS, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in autoimmune disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2010;2013:109–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, Chen X, Wu L, et al. [Significance of hemophagocytosis in diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis]. Zhongguo Shi Yan Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi 2009;2013:1064–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larroche C. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: diagnosis and treatment. Joint Bone Spine 2012;2013:356–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Favara BE, Feller AC, Pauli M, et al. Contemporary classification of histiocytic disorders. The WHO Committee On Histiocytic/Reticulum Cell Proliferations. Reclassification Working Group of the Histiocyte Society. Med Pediatr Oncol 1997;2013:157–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pachlopnik Schmid J, Schmid JP, Côte M, et al. Inherited defects in lymphocyte cytotoxic activity. Immunol Rev 2010;2013:10–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larroche C, Ziol M, Zidi S, et al. [Liver involvement in hemophagocytic syndrome]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2007;2013:959–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr 2007;2013:95–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imashuku S. Treatment of Epstein-Barr virus-related hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (EBV-HLH); update 2010. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011;2013:35–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henter JI, Tondini C, Pritchard J. Histiocyte disorders. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2004;2013:157–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen CE, Yu X, Kozinetz CA, et al. Highly elevated ferritin levels and the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;2013:1227–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.François B, Trimoreau F, Vignon P, et al. Thrombocytopenia in the sepsis syndrome: role of hemophagocytosis and macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Am J Med 1997;2013:114–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi N, Chubachi A, Kume M, et al. A clinical analysis of 52 adult patients with hemophagocytic syndrome: the prognostic significance of the underlying diseases. Int J Hematol 2001;2013:209–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buyse S, Teixeira L, Galicier L, et al. Critical care management of patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Intensive Care Med 2010;2013:1695–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henter J-I, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;2013:124–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuda H, Shirono K. Successful treatment of virus-associated haemophagocytic syndrome in adults by cyclosporin A supported by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Br J Haematol 1996;2013:572–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravelli A, Viola S, De Benedetti F, et al. Dramatic efficacy of cyclosporine A in macrophage activation syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2001;2013:108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yakushijin K, Mizuno I, Sada A, et al. Cyclosporin neurotoxicity with Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Haematologica 2005;2013:ECR11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ménard F, Besson C, Rincé P, et al. Hodgkin lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: a disorder strongly correlated with Epstein-Barr virus. Clin Infect Dis 2008;2013:531–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Kerguenec C, Hillaire S, Molinié V, et al. Hepatic manifestations of hemophagocytic syndrome: a study of 30 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;2013:852–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]