Abstract

Angiotensin II (angII) accelerates atherosclerosis, but the mechanisms are not fully understood. The aim of this study was to determine whether TGFβ is required for angII-induced atherosclerosis. Ldlr-null mice fed a normal chow diet were infused with angII or saline for 28 days. A single injection of TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 (2 mg/kg) prevented angII-induction of TGFβ1 levels, and strikingly attenuated angII-induced accumulation of aortic biglycan content. To study atherosclerosis, mice were infused with angII or saline for 4 weeks, and then fed Western diet for a further 6 weeks. 1D11 had no effect on systolic blood pressure or plasma cholesterol; however, angII-infused mice that received 1D11 had reduced atherosclerotic lesion area by 30% (P < 0.05). Immunohistochemical analyses demonstrated that angII induced both lipid retention and accumulation of biglycan and perlecan which colocalized with apoB. 1D11 strikingly reduced the effect of angII on biglycan but not perlecan. 1D11 decreased total collagen content (P < 0.05) in the lesion area without changing plaque inflammation markers (CD68 and CD45). Thus, this study demonstrates that neutralization of TGFβ attenuated angII stimulation of biglycan accumulation and atherogenesis in mice, suggesting that TGFβ-mediated biglycan induction is one of the mechanisms underlying angII-promoted atherosclerosis.

Keywords: proteoglycans, TGFβ neutralizing antibody, atherosclerosis initiation, renin-angiotensin system, low density lipoprotein retention, biglycan-apoB colocalization, angiotensin II

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a central regulatory system for cardiovascular function, and critically connected with atherosclerosis as well (1). Angiotensin II (angII) is the major bioactive peptide and effector of RAS and acts via binding to AT1 receptors. Daugherty and Cassis (2) reported that chronic infusion of angII for 28 days potentiated atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice receiving a high-fat diet. RAS blockade has been shown to not only attenuate the progression of atherosclerotic lesions in animals (3), but also has emerged as a therapy for human cardiovascular diseases (4, 5). Intensive research over the past decade reveals that the actions of angII on atherosclerosis include vascular inflammation (6, 7), generation of reactive oxygen species (8), and alterations of endothelial function (9). AngII was also demonstrated to induce the expression of extracellular matrix (ECM) components in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), including collagen (10), laminin (11), and proteoglycans (12). However, the mechanisms underlying angII-accelerated atherosclerosis have not been fully elucidated.

The “response to retention hypothesis” proposes that the subendothelial retention of the atherosclerotic lipoproteins (e.g., apoB-containing LDL) by ECM molecules such as proteoglycans via electrostatic attraction contributes to the initiation of atherosclerosis development (13, 14). Biglycan is a member of chondroitin sulfate/dermatan sulfate containing small leucine-rich proteoglycans and binds apoB-containing lipoproteins (15). Biglycan was shown to be the proteoglycan most colocalized with apoB in both human and mouse atherosclerosis (16–18). Overexpression of human Bgn by rat smooth muscle cells (SMCs) results in increased lipoprotein binding on ECM (19), further supporting a role for biglycan in the development of atherosclerosis. Mice expressing proteoglycan binding-defective LDL with severely defective binding to biglycan exhibited decreased atherosclerosis, providing direct evidence that proteoglycan-mediated lipoprotein retention is a key step in atherogenesis (20). Previous work in our laboratory demonstrated that angII infusion induced the accumulation of vascular biglycan, which colocalized with apoB in atherosclerotic lesions in Ldlr−/− mice (21). In addition, the AT1-receptor antagonist telmisartan was shown to reduce biglycan accumulation and atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice (22). However, it is still unknown if induction of biglycan by angII is required for atherosclerosis.

TGFβ is a strong stimulator of proteoglycan synthesis. Proteoglycans synthesized by TGFβ1-treated arterial SMCs exhibited glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chain elongation as well as increased binding to LDL (23). In addition to GAG elongation, TGFβ upregulates biglycan expression transcriptionally in cell culture (24, 25). Similarly, angII was shown to stimulate Bgn mRNA levels through TGFβ in mesangial cells (26) and in cardiac fibroblasts (27). Previous studies in our laboratory demonstrated that angII infusion transiently increased TGFβ levels and persistently increased vascular accumulation of biglycan in Ldlr-null mice, which led to increased atherosclerosis after dietary challenge (21). Furthermore, inhibition of TGFβ with the TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 prevented angII stimulation of biglycan synthesis in SMCs (21), suggesting that TGFβ may be a potential mechanism mediating angII-induced biglycan and atherosclerosis. In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that TGFβ is required for angII induction of biglycan and angII-promoted atherogenesis in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with University of Kentucky Animal Care Committee guidelines and conformed to Public Health Service policy on the humane care and use of laboratory animals. All experiments were performed using 10–12-week-old female LDL receptor-deficient (Ldlr-null) mice (C57BL6 background). All mice were housed in a temperature-controlled facility with 12 h light/dark cycles, and fed normal rodent chow ad libitum with free access to water. In some experiments, mice received 6 weeks of Western diet (0.15% cholesterol and 21% fat; Harlan Laboratories, catalog number 88137, Madison, WI) to induce the development of atherosclerosis.

Mouse models and treatments

Mice reaching 20 g were implanted subcutaneously with Alzet osmotic mini-pumps (model 1004; Alzet Scientific Products, Mountain View, CA) to receive angII (1,000 ng/kg/min) or saline for 28 days. At the time of pump implantation, mice were intraperitoneally injected once with an anti-TGFβ antibody (1D11, MAB1835, R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; 2 mg/kg) or a control antibody 13C4 (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ; 2 mg/kg). After 28 days mice were euthanized and blood was collected for metabolic assays and hearts, aortas, and carotids were harvested for determination of biglycan content.

For atherosclerosis studies, angII or saline pumps were removed after 28 days to ensure complete cessation of infusions, then the mice were fed a Western diet for the next 6 weeks to induce atherosclerosis as we have previously described (21). Mice did not receive Western diet during angII infusion as this is known to increase development of abdominal aortic aneurysms; mice developing aneurysms were excluded from the study. At the end of this study, blood and major organs including major vessels were collected for metabolic assays or atherosclerotic analysis.

Metabolic characterization

Mice were bled submandibularly and blood was collected on days 0, 1, 3, 7, and 28 after angII/saline pump implantation. Systolic blood pressure was measured in conscious mice using an automatic tail cuff apparatus coupled to a personal computer based-data acquisition system (RTBP1007; Kent Scientific, Litchfeild, CT), with each measurement performed at the same time of day by the same operator. For each measurement, 20 chronological readings were obtained from each mouse to yield a mean blood pressure of the day. Serum total cholesterol concentrations were determined using enzymatic cholesterol assay kits (Wako Chemical Co., Richmond, VA). Plasma TGFβ1 was measured with the TGFβ1 Emax® ImmunoAssay system (Promega, Madison, WI). Samples were acid activated for total TGFβ1 quantification.

Immunoblots

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described previously (21). In brief, aortas and carotids were harvested, total protein was extracted by TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and aortas were dissolved in 1% SDS. For carotids, protein samples after TRIZOL extraction underwent dialysis with 0.1% SDS to obtain maximal protein yield. Equal amounts of protein were treated with chondroitinase or heparinase III to remove GAG, then separated by SDS-PAGE using 8% gels (biglycan molecular mass 42 kDa; perlecan molecular mass 400 kDa) followed by immunoprobing with an anti-biglycan antibody (R and D Systems) or anti-perlecan antibody (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY). Blotting for β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO; AF2066) served as a loading control. Immunoblot quantification was then performed using ImageJ densitometry software (National Institutes of Health), and the relative proteoglycan protein content was calculated using proteoglycan density divided by actin density.

Quantification of atherosclerotic lesions

Atherosclerosis was quantified in three vascular beds: the aortic sinus, the aortic intimal surface, and the BCA as described previously (21). Aortic sinus sections (8 μm thick) were collected every 72 μm and BCA sections (5 μm thick) were collected every 125 μm, then stained with Oil Red O (Fluka, St. Louis, MO) and quantified using computer-assisted morphometry with Nikon Image software. Aortic intimal surface lesions were stained with Sudan V (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH) and then evaluated by en face quantification of lesions. All quantifications were performed in duplicate by observers blinded to the group assignments of the mice.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence microscopy

Immunohistochemical staining was performed as described previously (28). Briefly, frozen sections (8 μm thick) were preincubated with 0.9% hydrogen peroxide (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) as well as avidin/biotin blocking solution (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). After serum blocking, sections were incubated with CD45 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) overnight at 4°C.

For immunofluorescence staining, the primary antibodies used were as follows: CD68 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA); biglycan (R and D Systems); decorin (R and D Systems); perlecan (Accurate, Westbury, NY); and apoB (Biodesign International, Saco, ME). Autofluorescence was eliminated by Sudan black treatment (supplementary Fig. I). To validate colocalization, single sections were double-stained for apoB and biglycan, apoB and decorin, or apoB and perlecan and analyzed by confocal microscopy with the use of a Leica AOBS TCS SP5 inverted laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Mannheim, Germany). Negative controls were performed using isotype-matched irrelevant antibodies, no primary antibody, or no secondary antibody. Staining intensity was quantified using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Picro-Sirius stain

Interstitial collagens were detected with Sirius red stain followed by polarized microscopy (29). Frozen sections of aortic roots were fixed with cold alcohol, rinsed with distilled water, then incubated with 0.1% Sirius red dye (Direct Red 80, Sigma, #365548-56) in saturated picric acid (Fluka, #80456) for 90 min. After rinsing with 0.01N HCl and distilled water, sections were subsequently dehydrated with gradient ethanol followed by xylene, and cover-slipped. After staining, sections were observed under polarized light and photographed with the same exposure time for each section. Collagen content only within the atherosclerotic lesion area was quantified using Image-Pro software (supplementary Fig. II).

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical differences were assessed by two-way ANOVA to assess effects of angII versus saline and 13C4 versus 1D11, followed by pairwise comparisons by Holm-Sidak method using Sigma Stat software (Jandel Scientific). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 inhibits angII stimulation of TGFβ1 levels and vascular biglycan accumulation

Female Ldlr-null mice were infused with saline or angII (1,000 ng/kg/min) for 4 weeks via osmotic mini-pumps and blood was collected periodically for measurement of TGFβ1 levels. Compared with saline infusion, angII infusion induced a transient surge (3-fold) of plasma TGFβ1 concentrations in vivo (Fig. 1A; P < 0.05). There was no effect of 13C4 on angII-stimulated TGFβ however, a single injection of TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 (2 mg/kg body weight) given on the pump implantation day (day 0) prevented the induction of TGFβ1 concentrations by angII infusion (Fig. 1B; P < 0.05). After initiation of the Western diet TGFβ concentrations increased in all groups as expected (30) but there was no difference in TGFβ concentrations between groups during the diet part of the study (not shown). To determine whether 1D11 inhibits vascular biglycan content in vivo, aortas of Ldlr-null mice were collected after 4 weeks of angII or saline infusion. Immunoblot analysis revealed that biglycan content was increased by angII infusion with or without irrelevant control 13C4 injection (Fig. 1C, D). However, 1D11 reduced angII-stimulated biglycan content in a dose-dependent pattern: 0.2 mg/kg dose of 1D11 decreased angII-induced biglycan protein content by 50%, while 2 mg/kg dose of 1D11 decreased biglycan content by 75% (Fig. 1C, D). Based on these results all subsequent experiments used the 2 mg/kg dose of 1D11.

Fig. 1.

TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 inhibits angII stimulation of plasma TGFβ levels and aortic biglycan content. A: Female Ldlr-null mice were infused with angII or saline for 28 days and their blood was collected at days 0, 1, 3, 7, and 28 for ELISA assay for total TGFβ concentration. Shown are means ± SEM from n = 4–14 mice per group per time point. *P < 0.05 versus saline group. B: Female Ldlr-null mice were ip injected with either TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 (2 mg/kg) or irrelevant antibody control 13C4 (2 mg/kg) once immediately after implantation of osmotic mini-pumps filled with either angII or saline, and their blood was collected at days 0, 1, 3, 7, and 28 for ELISA assay for total TGFβ concentration. Shown are means ± SEM from n = 4–14 mice per group per time point. *The area under the curve for each group was calculated and angII + 13C4 differs significantly from the other groups, P < 0.01. C: Twenty-eight days after angII or saline infusions, mouse aortas were removed, and total aortic protein was extracted for immunoblot analysis. Actin is shown as the loading control. D: Densitometry quantification was performed on immunoblots. Shown are means ± SEM from n = 2–4 mice per group. Analysis by two-way ANOVA shows that P = 0.003 for angII versus saline, and P = 0.03 for 1D11 versus 13C4. *P < 0.05 by pair-wise comparison.

TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 attenuates atherosclerosis accelerated by angII

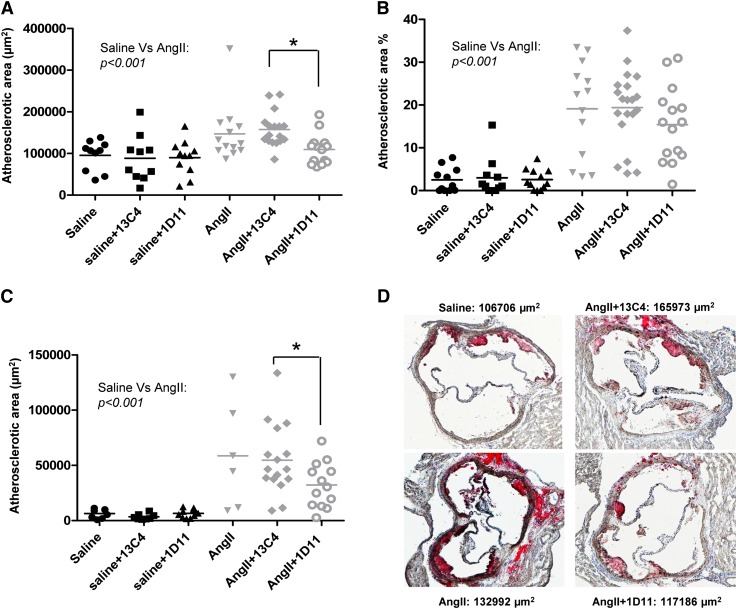

AngII is known for accelerating atherosclerosis in murine models (2, 28). To determine the effect of 1D11 on angII-induced atherosclerosis, female Ldlr-null mice received saline or angII (1,000 ng/kg/min) via osmotic pumps while fed normal chow for 4 weeks. To ensure the cessation of the infusions of agents, the pumps were removed on day 28 and the mice were then fed high-fat high-cholesterol Western diets for a further 6 weeks. AngII infusion elevated systolic blood pressure by approximately 20 mm Hg without affecting body weight, liver weight, or total cholesterol (Table 1). Neither 1D11 nor 13C4 had any effect on these parameters (Table 1). Similar to previous reports, mice infused with angII had increased atherosclerotic lesion areas (∼1.5-fold for aortic sinus, ∼8-fold for en face aortic surface, and ∼9-fold for the BCA) compared with mice infused with saline (Fig. 2). There was no significant effect of 13C4 on atherosclerosis; however, mice that received 1D11 and angII had decreased aortic root and BCA atherosclerotic lesion areas compared with mice that received angII alone or angII with 13C4 (Fig. 2A, C). Although 1D11-treated mice also exhibited a tendency toward decreased atherosclerosis in en face analysis, this effect did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2B). There was no effect of 1D11 on atherosclerosis in saline-infused mice suggesting TGFβ plays a role only in angII-accelerated atherosclerosis.

TABLE 1.

Effect of TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 on metabolic parameters

| Saline | Saline + 13C4 | Saline + 1D11 | AngII | AngII + 13C4 | AngII + 1D11 | ||

| Body weight (g) | 25.5 ± 0.9 | 25.1 ± 0.5 | 25.0 ± 0.8 | 26.0 ± 0.6 | 25.8 ± 0.9 | 25.7 ± 1.0 | N.S. |

| Liver weight (g) | 1.39 ± 0.07 | 1.42 ± 0.05 | 1.48 ± 0.06 | 1.50 ± 0.06 | 1.42 ± 0.08 | 1.43 ± 0.08 | N.S. |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 137 ± 4 | 142 ± 3 | 143 ± 4 | 155 ± 7 | 163 ± 2 | 165 ± 6 | Saline versus angII: P < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 1234 ± 54 | 1274 ± 50 | 1316 ± 24 | 1261 ± 45 | 1220 ± 45 | 1128 ± 36 | N.S. |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 403 ± 43 | 356 ± 19 | 475 ± 48 | 424 ± 39 | 291 ± 24 | 301 ± 29 | Significant interaction between factorsa |

Female Ldlr-null mice were infused with angII or saline via osmotic mini-pump for 28 days while fed normal chow. After 28 days of infusions, the pumps were removed and mice were fed a Western diet for 6 weeks. All mice received one ip injection of TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 (2 mg/kg) or irrelevant antibody control 13C4 (2 mg/kg) at the time of placement of pumps. Data are shown as means ± SEM for n = 8–20 mice per group., All parameters were determined after angII infusion plus 6 weeks of Western diet feeding except systolic blood pressure which was measured at the week 4 of AngII infusion. All analyses were done by two-way ANOVA. N.S., not significant.

A significant interaction between factors means that main effects cannot be properly interpreted.

Fig. 2.

TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 attenuates atherosclerosis accelerated by angII. Female Ldlr-null mice were infused with angII or saline via osmotic mini-pump for 28 days while fed normal chow. After 28 days of infusions, the pumps were removed and mice were fed a Western diet for 6 weeks. All mice received one ip injection of TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 (2 mg/kg) or irrelevant antibody control 13C4 (2 mg/kg) at the time of placement of pumps. Atherosclerotic area was determined in the aortic sinus (A), the en face aortic surface (B), and the BCA (C). Each symbol represents the lesion area of an individual mouse, and each horizontal line represents the mean for the group. All analyses were done by two-way ANOVA. * represents P < 0.05 by pair-wise comparison. D: Shown are representative photos of atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic sinus stained by Oil Red O. The atherosclerotic lesion area of the selected images is shown next to each image.

Effects of TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 on apoB-biglycan colocalization in angII-accelerated atherosclerotic lesions

In saline-infused mice injected with either 13C4 or 1D11, apoB (green) was widely distributed in lesions (Fig. 3A, B, E, F, J, K; supplementary Fig. I). The three major vascular proteoglycans (each stained in red) were predominantly located in the vessel wall or valves, and perlecan or decorin, but not biglycan, were also found in the fibrous cap of lesions (Fig. 3E, F, J, K). In contrast, angII-infused mice had much more intense apoB staining throughout vessel wall and lesions (Fig. 3C, D, G, H, L, M). AngII induced a prominent increase in biglycan protein content which colocalized with apoB (Fig. 3C, D, yellow) but there was no effect of angII on content or localization of decorin (Fig. 3L, M). Perlecan was also induced by angII, with increased content in both the plaque core (Fig. 3G, H) and the fibrous cap (data not shown), and perlecan also colocalized with apoB. However, mice injected with 1D11 not only exhibited a reduction in apoB intensity, but also demonstrated a striking attenuation of biglycan accumulation and colocalization with apoB in the lesions (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, there was no apparent effect of 1D11 on perlecan (Fig. 3H). Quantification of the immunostaining demonstrates increased biglycan and perlecan in angII-infused mice; 1D11 attenuated angII induction of biglycan but not perlecan (Fig. 3N, P). The effect of 1D11 on inhibiting angII-induced biglycan was confirmed by immunoblot analysis. Carotid biglycan content was increased by angII infusion, but this induction was completely prevented by 1D11 injection (Fig. 4A, B). However, in contrast, carotid perlecan content was not significantly affected by either angII infusion or 1D11 administration (Fig. 4C, D).

Fig. 3.

TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 attenuates biglycan accumulation and biglycan-apoB colocalization in atherosclerotic lesions. Sections of aortic sinus were double stained for both apoB (green) and one of the proteoglycans [biglycan (BGN): (A–D); perlecan (PLN): (E–H); and decorin (DCN): (J–M), all red] by immunofluorescence analysis and photos were taken using confocal microscopy. Nuclei were stained by DAPI (blue). Yellow demonstrates colocalization between apoB and each of the three proteoglycans. In each photo, the lumen is on the upper left side of the image. Photos shown are representative for 3–4 mice per group (group indicated at the top of each column of photos) magnified 630×. Biglycan (N) and perlecan (P) immunostained areas were quantified using ImageJ software. All analyses were done by two-way ANOVA with pair-wise comparisons. *P < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 attenuates biglycan accumulation in atherosclerotic carotids. Carotid arteries were collected at the end of the atherosclerosis studies and protein extracted and immunoblotted for biglycan (A) or perlecan (C); actin is shown as the loading control. Densitometry quantification was performed on blots (B) biglycan and (D) perlecan. Shown are means ± SEM from n = 2–4 mice per group. All analyses were done by two-way ANOVA with pair-wise comparisons. *P < 0.05.

Effects of TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 on plaque composition in angII-accelerated atherosclerotic lesions

After 6 weeks of Western diet feeding, Ldlr-null mice with previous angII infusion exhibited increased atherosclerotic lesion total collagen compared with mice with saline infusions (Fig. 5C, D; P < 0.05; supplementary Fig. IIA). However, when collagen content was adjusted for lesion area there were no significant differences between groups (data not shown). The increase in total collagen content by angII was inhibited by 1D11 compared with 13C4 control (Fig. 5N; P < 0.05). AngII also increased macrophage (CD68) staining intensity (Fig. 5E–H, P; P < 0.05) in atherosclerotic lesions, but there was no significant effect of 1D11 on lesion CD68 content (Fig. 5P). Similarly, there was no significant effect of 1D11 on lesion leukocytes (CD45) content (Fig. 5J–M; supplementary Fig. IIB), suggesting that TGFβ neutralizing antibody decreases plaque collagen without changing plaque inflammation.

Fig. 5.

Effect of TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 on plaque composition. Sections of aortic sinus were stained with Picro-Sirius red [panels (A–D) photographed under polarized light, magnified 100×], CD68 [panels (E–H) immunofluorescence, red], and CD45 [panels (J–M) immunohistochemistry, red, magnified 200×] for the content of collagen, macrophages, and leukocytes in the lesion area, respectively. Photos shown are representative for 4–8 mice per group (group indicated at the top of each column of photos). Notice that for Picro-Sirius red stain, collagen is mostly structural (in vessel or valves) in the saline group; however, collagen is found in the lesion area (white arrows) upon angII infusion. Quantification of collagen content (N) or CD68 intensity (P) within lesions is by ImageJ software. Shown are means ± SEM from 4–8 mice per group. All analyses were done by two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

In summary, our data demonstrate that a single injection of TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 prevented angII-induced stimulation of TGFβ1 plasma levels and vascular biglycan accumulation, and attenuated angII-induced atherosclerosis development. Although 1D11 had no apparent effect on inflammatory cell markers in atherosclerotic plaques, it reduced collagen content within the atherosclerotic lesions. Thus, we now demonstrate that TGFβ is involved in angII induction of biglycan accumulation and atherogenesis.

The role of TGFβ inhibition in the development of atherosclerosis has been intensively debated over decades, and the “protective cytokine hypothesis” has been broadly accepted (31). Lower concentrations of active TGFβ were found in subjects with advanced atherosclerosis (32). Tgfβ1+/− mice exhibited increased development of vascular lipid lesions when fed a lipid-enriched diet (33). Inhibition of TGFβ signaling by either anti-TGFβ1, -2, or -3 neutralizing antibody or recombinant TGFβRII:Fc led to a phenotype with increased inflammation and decreased fibrosis in Apoe−/− mice, reported by Mallat et al. (34) and Lutgens et al. (35), respectively. Further study by Wang et al. (36) also demonstrated that long-term administration of anti-TGFβ neutralizing antibody enhanced mouse susceptibility to AngII-induced aortic aneurysm formation with increased vascular inflammation. The mechanisms underlying TGFβ promotion of plaque stability involve not only stimulation of collagen biosynthesis, but also immune regulation through inhibition of activation of T cells (37).

Upregulation of TGFβ levels by utilizing gene transfer or transgenic mouse model has been shown to be protective (38, 39). However, excessive TGFβ signaling was shown to induce intimal and medial hyperplasia in porcine arteries (40). TGFβ1 transgenic mice demonstrated endothelial dysfunction and increased plaque size (41). These findings suggest the importance of spatial and temporal context for TGFβ signaling. As Grainger (42) pointed out, the upregulation of TGFβ at the right degree, in the right place, and at the right time can achieve its atheroprotective effects. However, our data suggest a pro-atherogenic role for TGFβ in the initiation of early atherosclerosis.

The results of the present study imply that even the brief induction of TGFβ by angII plays a role in the induction of atherosclerosis by angII. However, other groups have investigated the effect of inhibiting TGFβ on atherosclerosis development, with divergent results. Both Mallat et al. (34) and Lutgens et al. (35) evaluated atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice in which TGFβ was inhibited: Mallat et al. (34) used anti-TGFβ1, -2, -3 neutralizing antibody, whereas Lutgens et al. (35) used recombinant TGFβRII:Fc. The findings on lesion size by TGFβ inhibition differed between these two reports: an 80% increase in the Mallat et al. study (34), compared with a 37.5% reduction in the Lutgens et al. study (35). Our study showed a 30% decrease at aortic sinus by 1D11, which is consistent with Lutgens et al.’s finding. However, our study design has important differences from both Mallat et al. and Lutgens et al. (34, 35). In contrast to the Mallat et al. or Lutgens et al. studies in which TGFβ signaling was completely inhibited throughout the atherogenic period (34, 35), our study was designed only to prevent the transient increase in TGFβ induced by angII. These different study designs resulted in different plasma TGFβ concentrations: in the Mallat et al. studies plasma TGFβ concentrations were 1–2 ng/ml (34) whereas TGFβ levels in our mice after antibody injection never went below 4 ng/ml (Fig. 1B).

Both Mallat et al. and Lutgens et al. found more inflammation (demonstrated by MOMA-2, CD45, CD40L, and CD3 staining, respectively) and less collagen content in lesions (34, 35). Our results also demonstrated decreased collagen content in atherosclerotic lesions (Fig. 4), but no differences in macrophage (CD68) and leukocyte (CD45) staining intensity was observed in our study (Fig. 5).

In addition to evaluating atherosclerotic plaque composition, our study examined the effect of TGFβ neutralization on lesion proteoglycans. Our results demonstrate that TGFβ neutralizing antibody 1D11 (2 mg/kg) completely prevented angII-induced upregulation of plasma TGFβ levels (Fig. 1) but only attenuated angII-induced aortic biglycan accumulation by 75%. This suggests that other factors in addition to TGFβ might be involved in angII stimulation of biglycan in vivo. Indeed, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB was shown to increase Bgn mRNA expression in cardiac fibroblasts (43) and VSMCs (25). AngII was also demonstrated to transactivate PDGF-β receptor transiently in vitro (44, 45). Thus PDGF may play a role in angII stimulation of biglycan accumulation which could account for the lack of complete attenuation of angII-induced biglycan and atherosclerosis in mice given 1D11.

Furthermore, despite a striking reduction in vascular biglycan content, 1D11 attenuated atherosclerotic area by only a modest extent (around 30%), suggesting that biglycan is not the only mechanistic pathway underlying angII-accelerated atherosclerosis. AngII has multiple other pro-atherogenic actions that are not inhibited by 1D11 (46); however, this study is focused on the role of proteoglycans in angII-induced atherosclerosis. Both biglycan and perlecan have been found to accumulate in mouse lesions with distinct expression patterns (16); perlecan was shown to be distributed in the subendothelial regions in normal aorta and its expression was markedly induced in advanced lesions in both the plaque core and the fibrous cap (47), which was confirmed by our confocal microscopy results (Fig. 3). Furthermore, several studies have demonstrated a pro-atherogenic role for perlecan. Heterozygous Pln-deficient mice crossed to Apoe-null mice exhibited a significant reduction in lesion size when fed chow for 12 weeks, indicating the important role of perlecan in the early phase of atherosclerosis development (47). In addition, mice expressing heparan sulfate-deficient perlecan had reduced lesion formation with less lipoprotein binding in vitro (48), further confirming the role of perlecan in lipid retention and atherosclerosis. Our results demonstrate that angII-induced perlecan accumulation and colocalization with apoB still remained within the lesions even upon 1D11 treatment, suggesting that perlecan is independent of TGFβ. We propose that in mice both biglycan and perlecan mediate lipid retention and thus the modest decrease in atherosclerosis observed in 1D11-treated animals reflects the impact of TGFβ-induced biglycan; atherosclerosis is not further decreased because of perlecan-mediated lipid retention.

However, in contrast to mouse lesions where both biglycan and perlecan are predominant proteoglycans (16), perlecan does not appear to have a significant role in human atherosclerosis. A proportional decrease in heparan sulfate (which includes perlecan) and a corresponding increase in chondroitin/dermatan sulfate (which includes biglycan or decorin) were found associated with age and cholesterol content in human atherosclerosis (49). Moreover, both perlecan gene expression and its core protein were reduced in human atherosclerotic carotid plaques (50), suggesting a negative correlation of perlecan to human lesion formation. Thus, biglycan may play a more significant role than perlecan in human atherosclerosis development.

One question yet to be addressed is what cell types are involved in TGFβ-induced biglycan in our study. TGFβ has been shown to regulate the synthesis of proteoglycans in various cell types, including VSMCs (51), fibroblasts (24), endothelial cells (52), epithelial cells, and myoblasts (53). Biglycan is mainly synthesized by VSMCs (54) as well as endothelial cells in arterial wall (52). Evanko et al. (55) studied the distribution of proteoglycans and growth factors in primate atherosclerotic lesions, and illustrated that biglycan was deposited primarily in the matrix of VSMC-rich areas that are frequently observed adjacent to TGFβ1-positive macrophages, particularly beneath the luminal surface, supporting the possible mechanism that angII infusion increases TGFβ1 levels systemically and locally, and macrophage-derived or systemic TGFβ1 stimulates adjacent VSMCs to synthesize biglycan, which is then secreted to the ECM to promote lipid retention. Further studies need to be done utilizing cell-specific knockout/knockdown, e.g., VSMC-specific biglycan-deficient or macrophage-specific knockdown of TGFβ signaling to test this hypothesis.

In summary, we conclude that angII induction of atherosclerosis is mediated, at least in part, via the transient induction of TGFβ by angII which increases vascular biglycan content. In this case, prevention of TGFβ induction is atheroprotective, at least in Ldlr-null mice. This study provides in vivo data to support the involvement of TGFβ-mediated biglycan in the angII-induced atherosclerotic mouse model.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- angII

- angiotensin II

- BCA

- brachiocephalic artery

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- GAG

- glycosaminoglycan

- PDGF

- platelet-derived growth factor

- RAS

- renin-angiotensin system

- SMC

- smooth muscle cell

- VSMC

- vascular smooth muscle cell

Research reported in this study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers RO1HL-082772 and RO1HL-082772-0351 (both to L.R.T.).

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form two figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schmieder R. E., Hilgers K. F., Schlaich M. P., Schmidt B. M. 2007. Renin-angiotensin system and cardiovascular risk. Lancet. 369: 1208–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daugherty A., Cassis L. 1999. Chronic angiotensin II infusion promotes atherogenesis in low density lipoprotein receptor -/- mice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 892: 108–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Candido R., Jandeleit-Dahm K. A., Cao Z., Nesteroff S. P., Burns W. C., Twigg S. M., Dilley R. J., Cooper M. E., Allen T. J. 2002. Prevention of accelerated atherosclerosis by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in diabetic apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 106: 246–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox K. M. 2003. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study). Lancet. 362: 782–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yusuf S., Sleight P., Pogue J., Bosch J., Davies R., Dagenais G. 2000. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N. Engl. J. Med. 342: 145–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boring L., Gosling J., Cleary M., Charo I. F. 1998. Decreased lesion formation in CCR2-/- mice reveals a role for chemokines in the initiation of atherosclerosis. Nature. 394: 894–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kranzhöfer R., Browatzki M., Schmidt J., Kübler W. 1999. Angiotensin II activates the proinflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor-kappaB in human monocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 257: 826–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griendling K. K., Minieri C. A., Ollerenshaw J. D., Alexander R. W. 1994. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 74: 1141–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wassmann S., Czech T., van Eickels M., Fleming I., Bohm M., Nickenig G. 2004. Inhibition of diet-induced atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction in apolipoprotein E/angiotensin II type 1A receptor double-knockout mice. Circulation. 110: 3062–3067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato H., Suzuki H., Tajima S., Ogata Y., Tominaga T., Sato A., Saruta T. 1991. Angiotensin II stimulates collagen synthesis in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Hypertens. 9: 17–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regenass S., Resink T. J., Kern F., Buhler F. R., Hahn A. W. 1994. Angiotensin-II-induced expression of laminin complex and laminin A-chain-related transcripts in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Vasc. Res. 31: 163–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueroa J. E., Vijayagopal P. 2002. Angiotensin II stimulates synthesis of vascular smooth muscle cell proteoglycans with enhanced low density lipoprotein binding properties. Atherosclerosis. 162: 261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams K. J., Tabas I. 1995. The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15: 551–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tannock L. R., King V. L. 2008. Proteoglycan mediated lipoprotein retention: A mechanism of diabetic atherosclerosis. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 9: 289–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olin-Lewis K., Krauss R. M., La Belle M., Blanche P. J., Barrett P. H., Wight T. N., Chait A. 2002. ApoC-III content of apoB-containing lipoproteins is associated with binding to the vascular proteoglycan biglycan. J. Lipid Res. 43: 1969–1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kunjathoor V. V., Chiu D. S., O'Brien K. D., LeBoeuf R. C. 2002. Accumulation of biglycan and perlecan, but not versican, in lesions of murine models of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22: 462–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Brien K. D., Olin K. L., Alpers C. E., Chiu W., Ferguson M., Hudkins K., Wight T. N., Chait A. 1998. Comparison of apolipoprotein and proteoglycan deposits in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques: colocalization of biglycan with apolipoproteins. Circulation. 98: 519–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakashima Y., Fujii H., Sumiyoshi S., Wight T. N., Sueishi K. 2007. Early human atherosclerosis: accumulation of lipid and proteoglycans in intimal thickenings followed by macrophage infiltration. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 1159–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Brien K. D., Lewis K., Fischer J. W., Johnson P., Hwang J. Y., Knopp E. A., Kinsella M. G., Barrett P. H., Chait A., Wight T. N. 2004. Smooth muscle cell biglycan overexpression results in increased lipoprotein retention on extracellular matrix: implications for the retention of lipoproteins in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 177: 29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skålén K., Gustafsson M., Rydberg E. K., Hultén L. M., Wiklund O., Innerarity T. L., Borén J. 2002. Subendothelial retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in early atherosclerosis. Nature. 417: 750–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang F., Thompson J. C., Wilson P. G., Aung H. H., Rutledge J. C., Tannock L. R. 2008. Angiotensin II increases vascular proteoglycan content preceding and contributing to atherosclerosis development. J. Lipid Res. 49: 521–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagy N., Melchior-Becker A., Fischer J. W. 2010. Long-term treatment with the AT1-receptor antagonist telmisartan inhibits biglycan accumulation in murine atherosclerosis. Basic Res. Cardiol. 105: 29–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Little P. J., Tannock L., Olin K. L., Chait A., Wight T. N. 2002. Proteoglycans synthesized by arterial smooth muscle cells in the presence of transforming growth factor-beta1 exhibit increased binding to LDLs. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22: 55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kähäri V. M., Larjava H., Uitto J. 1991. Differential regulation of extracellular matrix proteoglycan (PG) gene expression. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 up-regulates biglycan (PGI), and versican (large fibroblast PG) but down-regulates decorin (PGII) mRNA levels in human fibroblasts in culture. J. Biol. Chem. 266: 10608–10615 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schönherr E., Järveläinen H. T., Kinsella M. G., Sandell L. J., Wight T. N. 1993 doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.7.1026. Platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta 1 differentially affect the synthesis of biglycan and decorin by monkey arterial smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb.13: 1026–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kagami S., Border W. A., Miller D. E., Noble N. A. 1994. Angiotensin II stimulates extracellular matrix protein synthesis through induction of transforming growth factor-beta expression in rat glomerular mesangial cells. J. Clin. Invest. 93: 2431–2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiede K., Stoter K., Petrik C., Chen W. B., Ungefroren H., Kruse M. L., Stoll M., Unger T., Fischer J. W. 2003. Angiotensin II AT(1)-receptor induces biglycan in neonatal cardiac fibroblasts via autocrine release of TGFbeta in vitro. Cardiovasc. Res. 60: 538–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daugherty A., Manning M. W., Cassis L. A. 2000. Angiotensin II promotes atherosclerotic lesions and aneurysms in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 105: 1605–1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Junqueira L. C., Bignolas G., Brentani R. R. 1979. Picrosirius staining plus polarization microscopy, a specific method for collagen detection in tissue sections. Histochem. J. 11: 447–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou X., Johnston T. P., Johansson D., Parini P., Funa K., Svensson J., Hansson G. K. 2009. Hypercholesterolemia leads to elevated TGF-beta1 activity and T helper 3-dependent autoimmune responses in atherosclerotic mice. Atherosclerosis. 204: 381–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grainger D. J. 2004. Transforming growth factor beta and atherosclerosis: so far, so good for the protective cytokine hypothesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24: 399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grainger D. J., Kemp P. R., Metcalfe J. C., Liu A. C., Lawn R. M., Williams N. R., Grace A. A., Schofield P. M., Chauhan A. 1995. The serum concentration of active transforming growth factor-beta is severely depressed in advanced atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 1: 74–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grainger D. J., Mosedale D. E., Metcalfe J. C., Bottinger E. P. 2000. Dietary fat and reduced levels of TGFbeta1 act synergistically to promote activation of the vascular endothelium and formation of lipid lesions. J. Cell Sci. 113: 2355–2361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mallat Z., Gojova A., Marchiol-Fournigault C., Esposito B., Kamate C., Merval R., Fradelizi D., Tedgui A. 2001. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta signaling accelerates atherosclerosis and induces an unstable plaque phenotype in mice. Circ. Res. 89: 930–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lutgens E., Gijbels M., Smook M., Heeringa P., Gotwals P., Koteliansky V. E., Daemen M. J. 2002. Transforming growth factor-beta mediates balance between inflammation and fibrosis during plaque progression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22: 975–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y., Ait-Oufella H., Herbin O., Bonnin P., Ramkhelawon B., Taleb S., Huang J., Offenstadt G., Combadiere C., Renia L., et al. 2010. TGF-beta activity protects against inflammatory aortic aneurysm progression and complications in angiotensin II-infused mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120: 422–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson A. K., Rudling M., Zhou X., Gorelik L., Flavell R. A., Hansson G. K. 2003. Disruption of TGF-beta signaling in T cells accelerates atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 112: 1342–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li D., Liu Y., Chen J., Velchala N., Amani F., Nemarkommula A., Chen K., Rayaz H., Zhang D., Liu H., et al. 2006. Suppression of atherogenesis by delivery of TGFbeta1ACT using adeno-associated virus type 2 in LDLR knockout mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 344: 701–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frutkin A. D., Otsuka G., Stempien-Otero A., Sesti C., Du L., Jaffe M., Dichek H. L., Pennington C. J., Edwards D. R., Nieves-Cintron M., et al. 2009. TGF-[beta]1 limits plaque growth, stabilizes plaque structure, and prevents aortic dilation in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29: 1251–1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nabel E. G., Shum L., Pompili V. J., Yang Z. Y., San H., Shu H. B., Liptay S., Gold L., Gordon D., Derynck R., et al. 1993. Direct transfer of transforming growth factor beta 1 gene into arteries stimulates fibrocellular hyperplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 90: 10759–10763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buday A., Orsy P., Godo M., Mozes M., Kokeny G., Lacza Z., Koller A., Ungvari Z., Gross M. L., Benyo Z., et al. 2010. Elevated systemic TGF-beta impairs aortic vasomotor function through activation of NADPH oxidase-driven superoxide production and leads to hypertension, myocardial remodeling, and increased plaque formation in apoE(-/-) mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 299: H386–H395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grainger D. J. 2007. TGF-beta and atherosclerosis in man. Cardiovasc. Res. 74: 213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tiede K., Melchior-Becker A., Fischer J. W. 2010. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulators of biglycan in cardiac fibroblasts. Basic Res. Cardiol. 105: 99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heeneman S., Haendeler J., Saito Y., Ishida M., Berk B. C. 2000. Angiotensin II induces transactivation of two different populations of the platelet-derived growth factor beta receptor. Key role for the p66 adaptor protein Shc. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 15926–15932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang C., Wu L. L., Liu J., Zhang Z. G., Fan D., Li L. 2008. Crosstalk between angiotensin II and platelet derived growth factor-BB mediated signal pathways in cardiomyocytes. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.). 121: 236–240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daugherty A., Lu H., Rateri D. L., Cassis L. A. 2008. Augmentation of the renin-angiotensin system by hypercholesterolemia promotes vascular diseases. Future Lipidol. 3: 625–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vikramadithyan R. K., Kako Y., Chen G., Hu Y., Arikawa-Hirasawa E., Yamada Y., Goldberg I. J. 2004. Atherosclerosis in perlecan heterozygous mice. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1806–1812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tran-Lundmark K., Tran P. K., Paulsson-Berne G., Friden V., Soininen R., Tryggvason K., Wight T. N., Kinsella M. G., Boren J., Hedin U. 2008. Heparan sulfate in perlecan promotes mouse atherosclerosis: roles in lipid permeability, lipid retention, and smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ. Res. 103: 43–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hollmann J., Schmidt A., von Bassewitz D. B., Buddecke E. 1989. Relationship of sulfated glycosaminoglycans and cholesterol content in normal and arteriosclerotic human aorta. Arteriosclerosis. 9: 154–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tran P. K., Agardh H. E., Tran-Lundmark K., Ekstrand J., Roy J., Henderson B., Gabrielsen A., Hansson G. K., Swedenborg J., Paulsson-Berne G., et al. 2007. Reduced perlecan expression and accumulation in human carotid atherosclerotic lesions. Atherosclerosis. 190: 264–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J. K., Hoshi H., McKeehan W. L. 1987. Transforming growth factor type beta specifically stimulates synthesis of proteoglycan in human adult arterial smooth muscle cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84: 5287–5291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaji T., Yamada A., Miyajima S., Yamamoto C., Fujiwara Y., Wight T. N., Kinsella M. G. 2000. Cell density-dependent regulation of proteoglycan synthesis by transforming growth factor-beta(1) in cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 1463–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bassols A., Massague J. 1988. Transforming growth factor beta regulates the expression and structure of extracellular matrix chondroitin/dermatan sulfate proteoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 263: 3039–3045 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dreher K. L., Asundi V., Matzura D., Cowan K. 1990. Vascular smooth muscle biglycan represents a highly conserved proteoglycan within the arterial wall. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 53: 296–304 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evanko S. P., Raines E. W., Ross R., Gold L. I., Wight T. N. 1998. Proteoglycan distribution in lesions of atherosclerosis depends on lesion severity, structural characteristics, and the proximity of platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta. Am. J. Pathol. 152: 533–546 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.