Abstract

Objectives

Mortality has declined in people with HIV infection, subsequent to the improved access to antiretroviral therapy (ART). We assessed the incidence and determinants of mortality among patients with HIV-1 infection who were started on ART in a referral treatment centre for HIV infection in Yaounde, Cameroon.

Design

Cohort study with baseline assessment between 2007 and 2008, and follow-up during 5 years until June 2012.

Setting

The accredited HIV treatment centre of the Yaounde Jamot Hospital in the capital city of Cameroon.

Participants

People living with HIV infection who started ART between 2007 and 2008 at the study centre.

Outcome measures

All-cause mortality over time; accelerated failure time models used to relate baseline characteristics to mortality occurrence during follow-up.

Results

Of the 1444 patients included, 827 (53.7%) were men, and the median age (25–75th centiles) was 38 (31–45) years. The median duration of follow-up was 14.1 (1.1–46.4) months, during which 235 deaths were recorded (cumulative incidence rate: 16.3%), including 208 (88.5%) during the first year of follow-up. Baseline predictors of mortality were male gender (adjusted HR 2.15 (95% CI 1.34 to 3.45)), active tuberculosis (2.35 (1.40 to 3.92)), WHO stages III–IV of the disease (3.63 (1.29 to 10.24)), low weight (1.03 (1.01 to 1.05)/kg), low CD4 count (1.04 (1.01 to 1.07)/10/mm3 lower CD4) and low haemoglobin levels (1.12 (1.00 to 1.26)/g/dL lower).

Conclusions

Mortality rate among patients with HIV is very high within the first year of starting ART in this centre. Early start of the treatment at a less advanced stage of the disease, and favourable levels of CD4 could reduce early mortality, but would have to be tested.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Article summary.

Article focus

To investigate mortality occurrence and determinants among patients with HIV-1 infection started on antiretroviral therapy (ART) in a major reference treatment centre.

Key messages

The mortality rate among patients with HIV is very high, particularly within the first year of starting ART in this centre.

Male gender, active tuberculosis, advanced stage of the disease, low CD4 count, low weight and low haemoglobin levels at baseline were significant predictors of all-cause mortality during follow-up.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The strengths of the study include the large sample size and the use of robust methods to relate baseline predictors to the mortality occurrence during follow-up.

The study was based on data collected from patient files and clinical registers, and as expected, there were missing data, particularly on the true outcome of patients who were lost-to-follow-up.

Introduction

HIV infection is a major global health problem. Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with about 68% of the global population with HIV, is the most affected region in the world.1 HIV-related mortality appears to be higher in developing countries than in developed countries.2 Hopefully, mortality rates are declining with the improved access to antiretroviral therapy (ART),3 while explaining factors for the residual deaths seem to vary significantly across populations. Studies in SSA have found that mortality rate is particularly high during the first year of starting ART,4 with male sex, cachexia, advanced stage of the disease, low CD4 count, anaemia, high viral load at baseline and poor adherence to treatments being the main determinants of mortality.5–8

In Cameroon, about 105 000 people living with HIV (PLHIV) infection were on ART by the end of the year 2011.9 A study conducted in 2006 in a rural unit for HIV treatment in the northern part of the country found a mortality rate of 20.2/100 person-years among patients with HIV receiving ART.10 This figure, however, has not been updated since 2007, the year of introduction of free access to ART in the country. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine the mortality rate and determinants among patients with HIV-1 infection started on ART in a reference treatment centre in Cameroon.

Participants and methods

Study setting and participants

The study was conducted in the accredited HIV treatment centre (ATC) of the Yaounde Jamot Hospital (YJH) in the capital city of Cameroon. The study setting has been described in details previously.11 12 In brief, YJH is the referral centre for tuberculosis and chest diseases for the capital city (Yaounde) and surrounding areas. It has an ATC that provides care to PLHIV. As of June 2011, a total of 2250 PLHIV were followed in the centre. Patients received at the ATC between January 2007 and December 2008, aged 18 years and above, who were started on ART were included in the study.

During the study period, PLHIV were started on ART in the presence of a CD4 count below 200/mm3 or superimposed conditions other than tuberculosis, compatible with the WHO stage IV of disease severity.13 Patients fulfilling these criteria were referred to the ATC for treatment inception and follow-up. A medical file was created under the supervision of the attending physician and included sociodemographic, clinical and biological data of the patient. Files of eligible patients were presented at weekly meetings during which the appropriate treatment regimen was decided. First-line treatment regimens included two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (zidovudine, lamivudine, tenofovir) and one non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (nevirapine or efavirenz). Second-line regimens comprised two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (zidovudine, didanosine, lamivudine, tenofovir) and a protease inhibitor (indinavir, lopinavir/ritonavir). These regimens were all dispensed to patients free of charge and they were all started on prophylactic treatment with co-trimoxazole. All patients had an interaction session with trained psychosocial advisors to improve adherence to prescribed therapies.

Patients registered at YJH's ATC are seen on a monthly basis for prescription renewal. For those on a regimen comprising zidovudine (AZT) and/or nevirapine (NVP), haemoglobin (AZT) and/or liver transaminase (NVP) levels are monitored at 2 weeks from starting treatment. A biological profile is requested every 6 months, comprising a CD4 count, full blood count, liver transaminases and creatine (only for patients receiving tenofovir), and results are recorded in the clinical files.

Outcome

During the study period, patients who failed to report for consultation for three consecutive months were traced by community liaison agents using the contact details on the file. All-cause mortality was considered for all deceased patients at any time after starting ART. Time-to-death (in months) was the interval from the start of ART to date of death (or date of the last recorded visit when the date of death was unknown). Loss-to-follow-up (defaulter) was defined as a patient who failed to return for consultation for three consecutive months and was unsuccessfully traced by liaison agents.14 Transfer was considered for patients who at any time were definitively transferred to receive care in another centre. The follow-up for all patients was until June 2012, death, transfer and loss-to-follow-up, whichever came first.

Data collection

For the purpose of this study, patients with HIV started on ART during the study period were identified via antiretroviral treatment registries. All patients with HIV-1 infection, aged 18 years and above, who were started on ART during this period were included in the study, and followed until June 2012. The study was approved by the regulatory board of YJH.

The following data were retrieved in the medical files of eligible patients: sex, baseline age (in years), residence (urban vs rural), weight in kg, presence of opportunistic infection, CD4 count (in cells/mm3), haemoglobin levels in g/dL, total lymphocytes and platelet counts, antiretroviral regimens; outcome (death, loss-to-follow-up, transfer out, still alive and followed up) and estimated time to outcome occurrence in months. The duration of follow-up for patients still actively followed up was censored in June 2012.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis used SPSS V.17.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and SAS/STAT V.9.1 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Results are presented as count and percentages, mean and SD or median and 25–75th centiles. The χ² test, Student t test and their non-parametric equivalents were used to compare the baseline characteristics. The Kaplan-Meier estimator and accelerated failure time models, implemented with the use of LIFETEST and LIFEREG procedures of SAS, were used to investigate the baseline characteristics associated with mortality during the first 60 months of follow-up (corresponding to the observed duration of follow-up for >95% of participants). Candidate predictors included age (in years), gender (male vs female), residency (rural vs urban), active tuberculosis, WHO stages of the disease (III–IV vs I–II), weight (in kg), platelet count (per 1000), CD4 count (per 10/mm3), haemoglobin level (in g/dL) and ART regimen (AZT vs no AZT). Candidate predictors were tested one at a time in a basic model that included gender and age as covariates. Then significant predictors (based on a p value <0.10) were entered together in a multivariable model, and significant ones kept in the final model alongside age and gender. The reference category (or direction of continuous predictors) was always rearranged as appropriate to identify levels associated with increased mortality risk. A p value <0.05 was used to characterise statistically significant results.

Results

Data available

In 2007 and 2008, a total of 1444 PLHIV (including 827 women (57.3%)) were started on ART at YJH's ATC. Medical files were available for all of them. However, data were missing on some characteristics for a few participants. Analyses for those characteristics are restricted to participants with valid data, and their number indicated where relevant. Furthermore, a total of 470 participants had missing data for at least one of the candidate predictors and were therefore excluded from the regression analysis. Compared with the excluded participants, the 974 participants included in the regression analysis had a similar age (38.3 vs 38.8 years, p=0.44) and mean CD4 count (102 vs 111/mm3, p=0.06). Furthermore, they had a similar proportion of men (42.5% vs 43.2%, p=0.82), a similar distribution across WHO stages of disease severity (p=0.75), a borderline higher prevalence of active tuberculosis (31.1% vs 26.6%, p=0.04), a borderline lower baseline weight (57.6 vs 59.1 kg, p=0.04) and lower platelet count (262 000 vs 243 000/mm3, p=0.03) and a significantly lower haemoglobin level (9.9 vs 10.4 g/dL, p<0.0001).

Baseline characteristics of the study population

The baseline demographic, clinical and biological characteristics of participants are summarised in table 1. The median age (25–75th centiles) was 38 (31–45) years overall, 40 (34–47) years in men and 35 (30–43) years in women, p<0.0001. In all, 85.6% of participants were urban dwellers and about the same proportion were started on ART at WHO stages III–IV of disease severity, similarly among men and women (both p≥0.82, table 1). The main opportunistic infection was tuberculosis, which was found in 428 (29.6%) patients, and was more frequent in men than in women (34.7% vs 27.9%, p=0.0003). The median CD4 count (25–75th centiles) was 99 (36–161)/mm3 overall, 89 (33–155) in men and 105 (39–166) in women (p=0.02).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and biological profile of patients with HIV started on antiretroviral therapy at the Yaounde Jamot Hospital in 2007 and 2008

| Characteristics* | Overall | Men | Women | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1444 | 617 | 827 | |

| Median age, years (25–75th centile) | 38 (31–45) | 40 (34–47) | 35 (30–43) | <0.0001 |

| Residence, n (%) | 0.98 | |||

| Urban | 1236 (85.6) | 528 (85.6) | 708 (85.6) | |

| Rural | 208 (14.4) | 89 (14.4) | 119 (14.4) | |

| Tuberculosis | 428 (29.6) | 214 (34.7) | 214 (27.9) | 0.0003 |

| Weight (kg), n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| <50 | 308/1322 (23.3) | 69/570 (12.1) | 239/752 (31.8) | |

| 50–60 | 535/1322 (40.5) | 204/570 (35.8) | 331/752 (44.0) | |

| >60, n | 479/1322 (36.2) | 297/570 (52.1) | 182/752 (24.2) | |

| Median (25–75th centile) | 57 (50–65) | 61 (54–68) | 54 (47.5–60) | <0.0001 |

| WHO stage, n (%) | 0.82 | |||

| I and II | 186/1295 (14.4) | 78/553 (14.1) | 108/742 (14.6) | |

| III and IV | 1109/1295 (85.6) | 475/553 (85.9) | 634/742 (85.4) | |

| Platelets, ×1000/mm3 | 244 (180–320) | 229 (173–309) | 259 (190–330) | 0.0005 |

| Total lymphocytes, ×10/mm3 | 130 (90–190) | 130 (90–201) | 130 (90–190) | 0.88 |

| CD4 (/mm3), n (%) | 0.21 | |||

| <50 | 468 (32.4) | 216 (30.5) | 256 (30.5) | |

| 50–99 | 257 (17.8) | 111 (18.0) | 142 (17.6) | |

| 100–200 | 562 (38.9) | 231 (37.4) | 331 (40.0) | |

| >200 | 157 (10.9) | 59 (9.6) | 98 (11.8) | |

| Median (25–75th centile) | 99 (36.2–161) | 89 (33–155) | 105 (39–166) | 0.02 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| <8 | 235/1388 (16.9) | 67/594 (11.3) | 168/794 (21.2) | |

| 8–10 | 506/1388 (36.5) | 178/594 (30.0) | 328/794 (41.3) | |

| >10 | 647/1388 (46.6) | 349 (58.7) | 298 (37.5) | |

| Median (25–75th centile) | 9.9 (8.5–11.2) | 10.5 (9–12) | 9.5 (8.1–10.7) | <0.0001 |

*For all characteristics with missing values, estimates are based on the subset of participants with valid data for each relevant characteristic, and new denominators always provided.

NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Follow-up and outcome

The median duration of follow-up (25–75th centiles) was 14.4 (1.0–46.2) months overall, 9.1 (0–44.1) months in men and 20.3 (1.3–47.3) months in women (p<0.0001). At the final evaluation, 235 participants (cumulative incidence rate 16.3%) were deceased, 590 (40.8%) were lost-to-follow-up, 173 (12%) had been transferred to another centre, while 446 (30.9%) were still under active follow-up in the centre. The median duration of follow-up (25–75th centiles) for non-fatal outcomes was 4.5 (0–23.8) months for defaulters, 8.2 (2.5–20.3) months for transfer out and 50.5 (45.9–56.7) months for active follow-up cases.

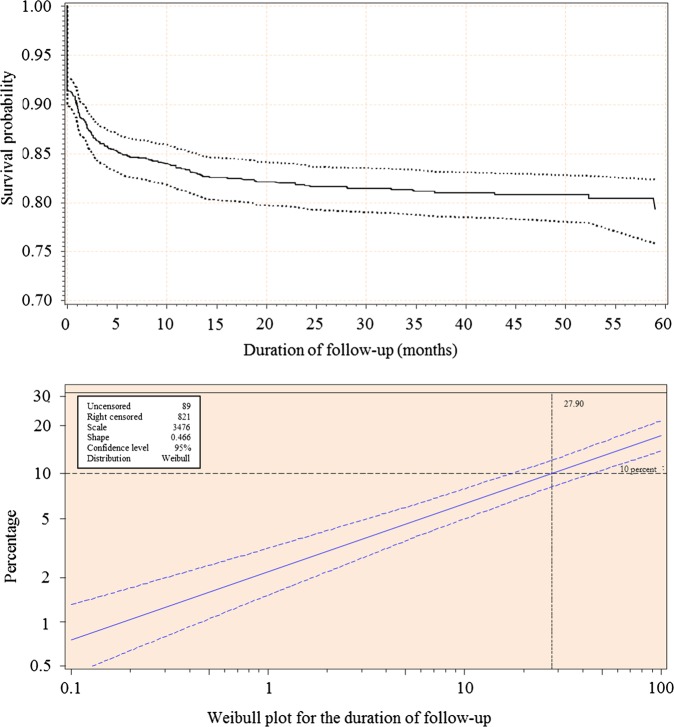

Of the 235 deaths recorded, 208 (88.5%) deaths occurred early (within the first year of ART) while 27 (11.5%) were late-occurring deaths. Overall, 54.9% of all deaths occurred within 1 month of starting ART, 19.6% between 1 and 3 months, 8.5% between 3 and 6 months and 5.5% between 6 and 12 months. The cumulative survival probability from the Kaplan-Meier estimators was 84.7% (95% CI 82.7 to 86.7) at 6 months, 83.3% (81.3 to 85.4) at 12 months, 81.7% (79.5 to 83.9) at 24 months and 79.3% (76.0 to 82.5) at 60 months of follow-up. The survival probability from the Kaplan-Meier estimators and the Weibull plot of the cumulative distribution function for all-cause mortality are depicted in figure 1. The cumulative mortality rate was 16.8% (79/470) among participants with missing data on at least one of the candidate predictor variables, and 16.6% (162/974) among those with valid data, p=0.93.

Figure 1.

Survival probability from the Kaplan-Meier estimator (upper panel) and the Weibull plot showing the cumulative distribution function for mortality during the follow-up of patients with HIV infection who started antiretroviral treatment at the Yaounde Jamot Hospital in 2007 and 2008.

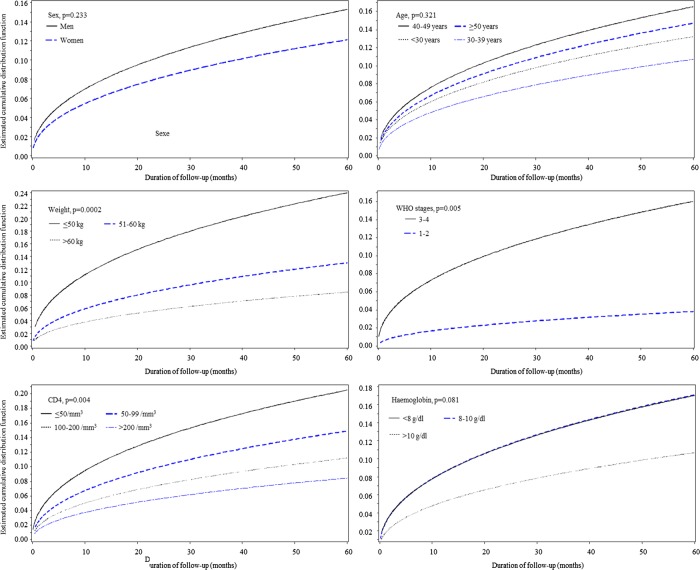

Determinants of all-cause mortality

The estimated cumulative distribution function for all-cause mortality by major subgroups is depicted in figure 2. In sex-adjusted and age-adjusted analyses, male sex, active tuberculosis, WHO stages III–IV of the disease, lower weight, lower CD4 count and lower baseline haemoglobin level were potential determinants of all-cause mortality (table 2). In the multivariable Weibull regression models with simultaneous adjustment for age, sex and all the potential factors, all determinants remained significantly associated with all-cause mortality during follow-up (table 2). Effect estimates (HR) and 95% CIs were 2.15 (1.34 to 3.45) for male sex, 2.35 (1.40 to 3.92) for active tuberculosis, 3.63 (1.29 to 10.24) for the WHO stages III–IV of disease severity, 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05)/kg lower weight, 1.04 (1.01 to 1.07)/10 lower CD4/mm3 and 1.12 (1.00 to 1.26) for each g/dL lower baseline haemoglobin (table 2).

Figure 2.

Estimated cumulative distribution function for all-cause mortality by major subgroups among patients with HIV infection who started antiretroviral treatment at the Yaounde Jamot Hospital in 2007 and 2008.

Table 2.

Determinants of all-cause mortality among HIV-positive patients started on antiretroviral therapy (n=1444)

| Age and sex adjusted |

Multivariable adjusted |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

| Age, per year | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.03) | 0.56 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.37 |

| Male sex | 1.44 (0.94 to 2.11) | 0.10 | 2.15 (1.34 to 3.45) | 0.002 |

| Rural residency | 1.14 (0.62 to 2.09) | 0.68 | – | |

| Active tuberculosis | 1.59 (0.97 to 2.61) | 0.07 | 2.35 (1.40 to 3.92) | 0.002 |

| WHO stages III–IV | 4.57 (1.68 to 12.47) | 0.004 | 3.63 (1.29 to 10.24) | 0.02 |

| Weight, per kg lower | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06) | 0.0002 | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05) | 0.01 |

| Platelet count, per 1000 lower | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.53 | – | |

| CD4 count, per 10/mm3 lower | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.09) | 0.003 | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.07) | 0.02 |

| Haemoglobin, per g/dL lower | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.26) | 0.02 | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.26) | 0.05 |

| AZT-based regimens | 0.91 (0.51 to 1.62) | 0.76 | – | |

AZT, zidovudine.

Discussion

This study conducted in a referral centre for tuberculosis and HIV care in Cameroon revealed a high mortality rate among patients started on ART, with the large majority of deaths occurring during the first year of starting the treatment. Male gender, active tuberculosis, advanced stage of the disease, low CD4 count, low weight and low haemoglobin levels at baseline were significant predictors of all-cause mortality during follow-up. Accounting for these factors may help in refining the prescription of ART and improving the outcome of care among patients with HIV infection.

The survival probability at 1 year of follow-up after starting ART was found to be much lower (83.3% vs 77%) in a previous study among 1187 PLHIV infection in a rural setting in the Northern part of Cameroon.10 This study, however, was conducted prior to 2007, the year of the implementation of the programme of free access to ART in the country, which suggests that this strategy has most likely improved survival among PLHIV in the country. It can also be speculated that the difference between this previous study and our finding just reflects differences in the level of care provided in a referral centre like ours, and a rural centre where care can be very basic. The similarities in the baseline profile of participants across the two studies are in support of this hypothesis. For instance, in both studies, over 85% of participants were started on ART while at the WHO stage III or IV of disease severity, while the pre-ARV CD4 count was lower than 50/mm3 in over a quarter of participants at baseline. However, the 1-year survival rate in our study is within the range of those reported in previous studies. In a recent meta-analysis of those studies, the pooled estimated 1-year probability of death from studies conducted in Africa was 17% (95% CI: 11% to 24%).6 15

Predictors of mortality identified in our study were essentially those described in existing reports.6 15 The adverse profile of modifiable risk factors clearly suggests that patients with HIV in our centre are started on ART at an advanced stage of the disease. This most likely reflects the fact that in this setting, with the exception of screening in particular circumstances such as during pregnancy or presurgical interventions, PLHIV mostly get screened only when they seek medical care with clinical symptoms. This is a common attitude across Africa, and may explain the higher early mortality rate on ART in Africa, compared with other parts of the world.6 In addition to the advanced clinical stage of the disease on the WHO scale at presentation, body weight, CD4 count and haemoglobin levels were low at baseline and all significantly associated with a high risk of mortality during follow-up as previously reported.5 8 It is worth noting that at the time this study was conducted, most patients were started on ART at a CD4 count below 200/mm3. Recent WHO recommendations favour ART initiation at a CD4 count below 350/mm3. Their uptake may potentially reduce early mortality rate as a result of many patients starting treatment at favourable CD4 levels. The prevalence of active tuberculosis in our study was possibly inflated by the nature of the study setting as a referral centre for tuberculosis treatment, where most patients with both HIV and tuberculosis are more likely to be referred for care. The resulting subsample of participants with both conditions has possibly increased our statistical power for uncovering baseline active tuberculosis as a risk factor for mortality among PLHIV started on ART. Such an association has been inconsistently reported in previous studies.6 10 16

Free access to ART was introduced in Cameroon in May 2007.17 We have recently reported rates of non-adherence to ART to be as high as 34% among patients with HIV receiving chronic care at YJH in the era of free access to ART.12 In the absence of any assessment of the adherence to ART in the current study, it is difficult to speculate on a contribution, if any, of non-adherence to ART to the observed high mortality in our study. However, such an effect is most likely marginal in this setting where mortality mostly occurs early when patients have not been exposed to ART enough to derive therapeutic benefits. Furthermore, the existing instruments for measuring adherence to ART are most likely unsuitable for investigating premature mortality risk. The main non-modifiable risk factor of mortality in our study was male sex. This was not fully explained by sex differences in the level of other risk factors. Indeed, with the exception of baseline CD4 count, which was lower in men, other factors were equally distributed among men or women or rather showed more favourable levels in men. Other studies have shown that adherence to prescribed ART was better in women than in men,18 which can explain differing rates of mortality between men and women started on ART.

Our study has some limitations, including the missing data, which are expected for a study conducted on data collected from patients’ files and when dealing with large numbers of participants. Drop-out through losses to follow-up potentially included deceased patients, and may be in high proportion based on some studies.19 Therefore, the reported mortality rate in our study is most likely underestimated. But such a bias is unlikely to affect the associations of major risk factors with mortality outcome as shown elsewhere.10 In the absence of any evaluation of the adherence to ART, particularly among early mortality survivors, we were unable to investigate a potential effect of non-adherence to ART on mortality risk in the current study. Our study also has major strengths, including the large sample size, which increased our statistical power to reliably characterise the predictors of mortality. The mortality rate following ART initiation, as found in our study and other published studies, is not constant over time. It is very high in the early months of starting the treatment, and subsequently drops and stabilises at a much lower rate. Many previous studies have been based on statistical methods that assume constant mortality rates over time such as the person-year methods, and have quite likely generated less reliable estimates of the association of predictors with mortality risk. We have attempted to address this limitation by applying the accelerated failure time models in our study. Unlike Cox models for instance, regression parameter estimates from accelerated failure time models are robust to the omitted covariates, and are unaffected by the choice of probability distribution.

In conclusion, the mortality rate among patients with HIV-1 infection started on ART in this setting remains unacceptably high. Deaths occur mostly within the first year of starting treatment and essentially among patients with clinical and biological profiles compatible with an advanced stage of the disease at the time when antiretroviral treatment is started. Strategies for early detection of patients with HIV at the clinically asymptomatic stages, followed by early initiation of ART, need to be developed and tested in this setting. Recent updates of the country's guidelines for HIV treatment, recommending prescription of ART at a CD4 count lower than 350/mm3, have a potential for significantly reducing premature mortality among people with HIV in this setting.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: VP-M collected and coanalysed the data and drafted the manuscript. EWP-Y conceived the study, supervised the data collection, coanalysed the data and drafted the manuscript. APK contributed to the study design, data analysis, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. CK supervised the data collection and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Yaounde Jamot Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2012. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2012/gr2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012_en.pdf (accessed 6 May 2013)

- 2.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet 2006;367:817–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palella FJ, Baker RK, Moorman AC, et al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;43:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marazzi MC, Liotta G, Germano P, et al. Excessive early mortality in the first year of treatment in HIV type 1-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2008;24:555–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kouanda S, Meda IB, Nikiema L, et al. Determinants and causes of mortality in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Burkina Faso: a five-year retrospective cohort study. AIDS Care 2012;24:478–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta A, Nadkarni G, Yang WT, et al. Early mortality in adults initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e28691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fregonese F, Collins IJ, Jourdain G, et al. Predictors of 5-years mortality in HIV-infected adults starting highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in Thailand. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;60:91–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurent C, Meilo H, Guiard-Schmid JB, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in public and private routine health care clinics in Cameroon: lessons from the Douala antiretroviral (DARVIR) initiative. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:108–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministère de la Santé Publique Rapport national de suivi de la déclaration politique sur le VIH/SIDA Cameroun. 2012

- 10.Sieleunou I, Souleymanou M, Schonenberger AM, et al. Determinants of survival in AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy in a rural centre in the Far-North Province, Cameroon. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14:36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pefura Yone EW, Betyoumin AF, Kengne AP, et al. First-line antiretroviral therapy and dyslipidemia in people living with HIV-1 in Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Ther 2011;8:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pefura Yone EW, Soh E, Kengne AP, et al. Non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Yaounde: prevalence, determinants and the concordance of two screening criteria. J Infect Public Health 2013;6:307–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministère de la Santé Publique du Cameroun. 2007. Directives nationales de prise en charge par les antirétroviraux des personnes (adultes et adolescents) infectés par le VIH. Yaoundé.

- 14.Wools-Kaloustian K, Kimaiyo S, Diero L, et al. Viability and effectiveness of large-scale HIV treatment initiatives in sub-Saharan Africa: experience from western Kenya. AIDS 2006;20:41–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biadgilign S, Reda AA, Digaffe T. Predictors of mortality among HIV infected patients taking antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: a retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Ther 2012;9:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amuron B, Levin J, Birunghi J, et al. Mortality in an antiretroviral therapy programme in Jinja, south-east Uganda: a prospective cohort study. AIDS Res Ther 2011;8:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Public Health, Republic of Cameroon National AIDS Control Committee: Towards universal access to care and treatment for adults and children living with HIV/AIDS in Cameroon. Progress Report N° 4 2006

- 18.MacPherson P, Moshabela M, Martinson N, et al. Mortality and loss to follow-up among HAART initiators in rural South Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2009;103:588–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu JK, Chen SC, Wang KY, et al. True outcomes for patients on antiretroviral therapy who are ‘lost to follow-up’ in Malawi. Bull World Health Organ 2007;85:550–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.