Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii (AB) is a common pathogen found in patients with hospital-acquired pneumonia all over the world. Community-acquired AB pneumonia, however, is very rare and has seldom been reported in Asia-Pacific countries. Community-acquired AB pneumonia has a fulminant course and is associated with a higher mortality than hospital-acquired AB pneumonia. In Korea, no case of fatal community-acquired AB pneumonia has been reported to date. Here, we describe the first fatal case of fulminant community-acquired AB pneumonia in Korea.

Keywords: Acinetobacter baumannii, Community-acquired pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii (AB) is an aerobic gram-negative coccobacillus commonly found in soil and fresh water. It is a major pathogen associated with hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) [1]. In rare cases, AB can cause community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), reported to occur primarily during the humid seasons in Asia-Pacific countries [2-5].

Clinically, community-acquired Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia (CAP-AB) progresses more rapidly than its HAP counterpart, with a higher mortality rate due to frequent antibiotic tolerance [2-5]. A putative case of CAP-AB was reported in Korea, wherein the bacterial strain isolated was sensitive to most antibiotics and the patient had a good prognosis [6]. Here, we report the first case of a patient in Korea with rapidly progressing and fatal CAP-AB who succumbed within 36 hours of hospital admission.

CASE REPORT

A 53-year-old male patient visited the emergency room for worsening symptoms of productive cough, fever, and chills that developed the day before. The patient, with no specific occupation, had a 30-pack/year history of cigarette smoking and consumed alcohol in moderation. He was successfully treated for CAP in another hospital 2 years prior and had experienced no other problems. Upon admission, the patient appeared acutely ill. His blood pressure was 82/46 mmHg, respiratory rate was 22 breaths per minute, pulse rate was 120 beats per minute, and body temperature was 40℃. A regular heart rhythm was observed and there were coarse breathing sounds with crackles on the right lower lung field.

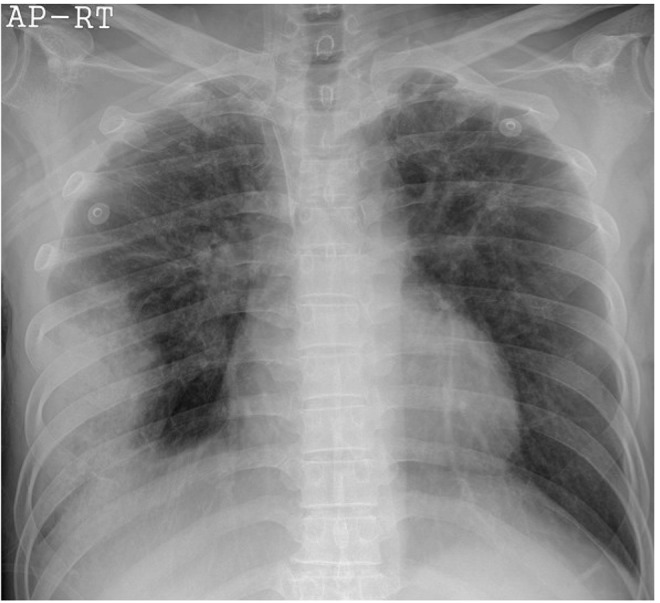

The laboratory chemistry values were as follows: white blood cell count of 11,500/mm3 with 86.1% neutrophils, 11.5% lymphocytes, 1.9% monocytes, 0.2% eosinophils; hemoglobin 14.4 g/dL; platelet count 188,000/mm3; C-reactive protein 1.28 mg/dL. The arterial blood gas analysis at room air was pH of 7.47, pCO2 of 22.4 mmHg, pO2 of 52.5 mmHg, HCO3- of 16 mmol/L, and O2 saturation of 89%. Blood chemistries showed a blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/creatinine (Cr) level of 9/2.05 mg/dL and the serum sodium, potassium, and chloride were 139, 4.1, and 105 mmol/L, respectively. The urine sodium was 19 mmol/L, urine Cr was 222.31 mg/dL, and the calculated fractional excretion of sodium was 0.1%. A simple chest radiograph showed moderate patchy consolidation in the right lower lobe (Fig. 1). We made a presumptive diagnosis of sepsis caused by CAP.

Figure 1.

A simple chest radiograph obtained in the emergency room shows moderate patchy consolidation in the right lower lung field.

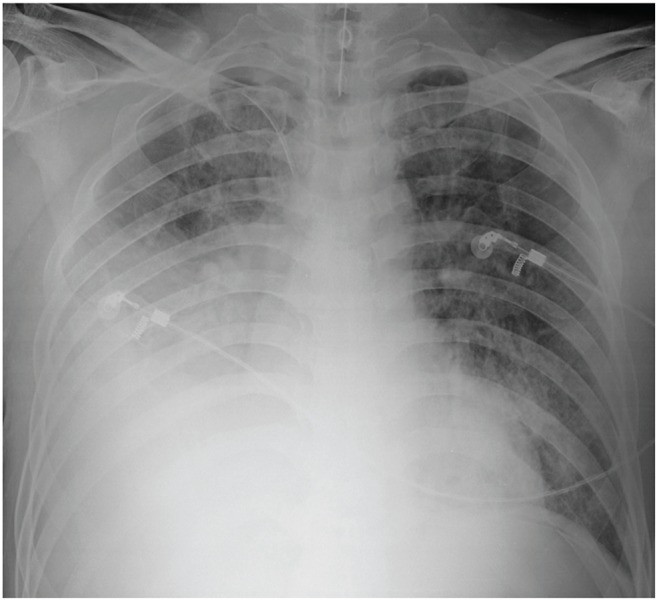

Septic shock was suspected due to low blood pressure. A central line catheter was promptly inserted, along with fluid resuscitation, and oxygen was administered via nasal cannula. Cultures of blood, sputum, and urine samples were also completed. Empiric piperacillin/tazobactam with ciprofloxacin injections were administered simultaneously. The patient was admitted into the intensive care unit for directed therapy of septic shock. The initial APACHE II score was 25. Low blood pressure persisted after vigorous fluid therapy; thus, the vasoactive agent norepinephrine was administered. Vasopressin was later added when the mean arterial pressure did not normalize. Sixteen hours after admission, respiratory distress worsened, resulting in acute respiratory failure with arterial blood gas analysis showing a pH of 7.085, pCO2 of 61.4 mmHg, and HCO3- of 19 mmol/L. The patient was immediately intubated with mechanical ventilation at FiO2 of 1.0 and positive end expiratory pressure at 14 cmH2O; however, hypoxia persisted and respiratory and metabolic acidosis continued to deteriorate. Twenty-four hours after admission, follow-up arterial blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.096, pCO2 of 63.7 mmHg, pO2 of 77.6 mmHg, HCO3- of 20 mmol/L, and O2 saturation of 89%. The follow-up chest radiograph showed more exacerbated consolidation in the right lung field with the beginning of patchy opacities in the left lower lobe (Fig. 2). The antibiotics were then switched to meropenem with teicoplanin. Twenty-eight hours after admission, oliguria ensued along with deteriorating acute kidney injury with BUN/Cr at 26/3.66 mg/dL. Continuous renal replacement therapy was promptly initiated. After 36 hours of intensive treatment, septic shock and acute respiratory failure did not improve and the patient went into cardiac arrest. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed for 30 minutes but the patient did not recover.

Figure 2.

After 24 hours, right lung field consolidation worsened and new mild patchy opacities developed in the left lower lung field.

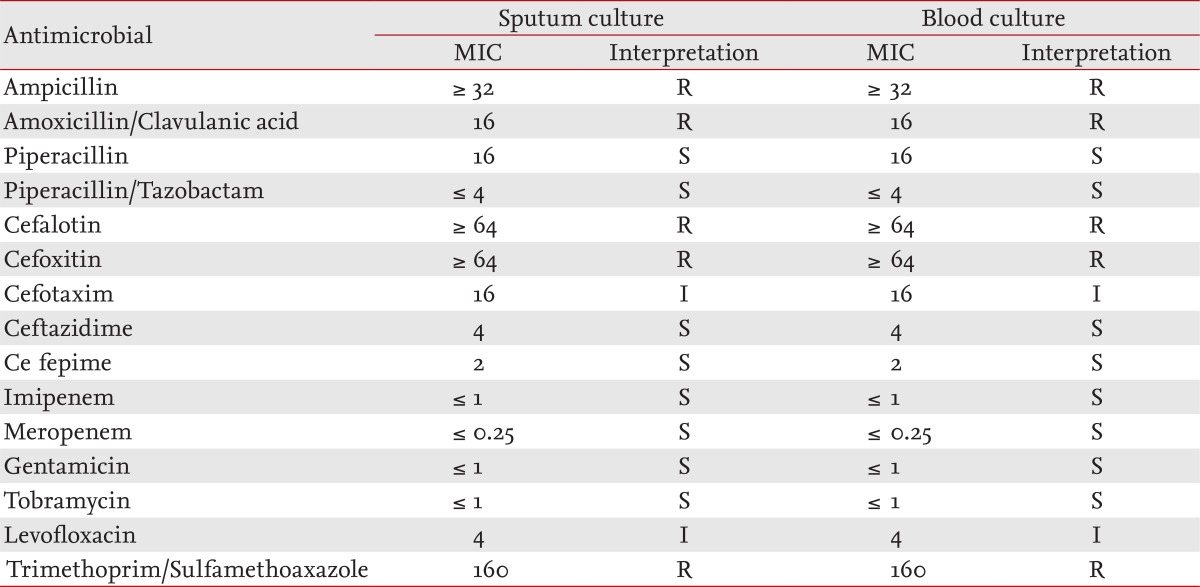

After the patient expired, AB was identified in both the culture of sputum and two pairs of blood samples taken during the emergency room visit. Bacterial sensitivity to antibiotics was measured using isolates from both sputum and blood cultures. The bacterial isolate was susceptible to piperacillin/tazobactam, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem, meropenem, gentamicin, and tobramycin; tolerant to ampicillin, amoxacillin/clavulanic acid, cafalotin, cefoxitin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; and moderately tolerant to cefotaxime and levofloxacin (Table 1). A VITEK device (VITEK 2, Biomerieux, Marcy I'Etolile, France) was used for culturing, and the sensitivity test was conducted in accordance to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute.

Table 1.

The antibiotic sensitivity test

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; R, resistant; S, sensitive; I, intermediate.

DISCUSSION

This is the first case of fatal CAP-AB reported in Korea. It illustrates the speed of infection; the patient was in shock from the time of admission and his clinical condition rapidly progressed until the patient expired 36 hours later. AB was confirmed from both the sputum and two pairs of blood cultures with the same antibiotic susceptibility profile.

In Asia-Pacific countries including Korea, AB is a known pathogen causing a high incidence of HAP (16% to 38%), as compared to Western countries [7]. Patients with HAP-AB tend to do poorly and have a relatively higher mortality rate, as compared to those with HAP caused by other pathogens. CAP-AB is also more frequent in Asia-Pacific countries than its Western counterparts and the relationship between CAP and AB has rarely been reported in Asia-Pacific countries. Based on data from reported cases in these countries, it appears that CAP has a worse prognosis than HAP [2-5]. Reports have suggested that mortality in CAP-AB can reach 58% to 64% [3,5,8]. A review of CAP-AB cases in Southeast Asia showed that six out of eight patients die as a result. The patients usually present with poor clinical prognosis and succumb to the disease from 13 hours to 6 days after presentation, primarily in the early stages of hospitalization [2].

Epidemiologic studies of CAP-AB have shown that this pathogen occurs in subtropical regions with high humidity. Less than 10% of all CAP outbreaks in Australia and Taiwan are due to AB [3,4]. A presumed CAP-AB had been previously reported in Korea by Han et al. [6]. However, this case showed different clinical characteristics and the bacterial isolate had a different antibiotic susceptibility profile, as compared to cases from other Asia-Pacific countries. The present case of CAP-AB occurred in Korea's Jeju island, which has a climate similar to other Asia-Pacific countries. Its clinical progress was also similar to the severe pneumonia cases reported in other Asia-Pacific countries, where the patient expired within a very short time (36 hours) after the admission.

The average age of patients with CAP-AB is between 56 to 73 years [3-5], and the known risk factors are smoking history, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, renal diseases, and malignancies [2-5]. Affected patients usually experience sudden fever and chills accompanied by sudden cough with purulent sputum, chest pain, and respiratory distress [2,3,5,8]. In many cases, bacteremia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, or shock has already occurred at presentation [2,3,8], and the chest radiograph typically shows lobar consolidation [3,5,8]. The patient in this report was 53 years old with a 30-pack/year history of cigarette smoking and consumed alcohol moderately. His clinical presentation began with an acute fever and he had bacteremia and was in shock at the time of admission, with the chest radiograph showing lobar consolidation in the right lower lobe. This patient had been hospitalized for pneumonia 2 years before but a past history of pneumonia has not been reported to correlate with CAP-AB.

Empirical antibiotics such as ceftazidime with aminoglycoside, ticarcillin/clavulanate, and imipenem are recommended for CAP-AB. Studies have shown that CAP-AB shows good response to antipseudomonal penicillins, imipenem, aminoglycoside, ampicillin/sulbactam, and ciprofloxacin [2,3,8]. In contrast, a study conducted in Hong Kong revealed that, compared to other pathogens causing HAP-AB, CAP-AB showed resistance to ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole and tobramycin [5]. The AB isolated in this case was susceptible to antipseudomonal penicillin (piperacillin/tazobactam), ceftazidime, cefepime, meropenem, and tobramycin; was tolerant to amoxacillin/clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; and was moderately resistant to cafotaxime and levofloxacin. It was resistant to ciprofloxacin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. The antibiotic sensitivity test result was similar to that of the study in Hong Kong [5].

Studies have reported that differences in the pathogens account for the higher mortality in CAP-AB, as compared to HAP-AB. One study suggested that the AB isolated from CAP-AB has different antibiotic sensitivity patterns, as compared to those from HAP-AB [5]. Another study showed that the pathogens of CAP-AB have different genetic features to those of HAP-AB [4,9]. Pulse-field gel electrophoresis of strains obtained from patients with CAP-AB suggested that community-acquired strains of AB were composed of a large variety of unrelated strains and were distinct from the more closely related strains found in hospitals [9,10]. Therefore, community-acquired AB may be more problematic due to the different genetic make-up of the pathogen and more research is needed to sort through these challenges.

This case report describes the first Korean case of fatal CAP-AB. The infection rapidly progressed and resulted in the patient succumbing to the illness shortly after admission. We believe that, as in other Asia-Pacific countries, an outbreak of fatal CAP-AB is possible in Korea.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.

References

- 1.Fournier PE, Richet H. The epidemiology and control of Acinetobacter baumannii in health care facilities. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:692–699. doi: 10.1086/500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ong CW, Lye DC, Khoo KL, et al. Severe community-acquired Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia: an emerging highly lethal infectious disease in the Asia-Pacific. Respirology. 2009;14:1200–1205. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen MZ, Hsueh PR, Lee LN, Yu CJ, Yang PC, Luh KT. Severe community-acquired pneumonia due to Acinetobacter baumannii. Chest. 2001;120:1072–1077. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anstey NM, Currie BJ, Hassell M, Palmer D, Dwyer B, Seifert H. Community-acquired bacteremic Acinetobacter pneumonia in tropical Australia is caused by diverse strains of Acinetobacter baumannii, with carriage in the throat in at-risk groups. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:685–686. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.2.685-686.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung WS, Chu CM, Tsang KY, Lo FH, Lo KF, Ho PL. Fulminant community-acquired Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia as a distinct clinical syndrome. Chest. 2006;129:102–109. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han SH, Na DJ, Yoo YW, et al. A case of probable community acquired Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2007;63:273–277. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song JH Asian Hospital Acquired Pneumonia Working Group. Treatment recommendations of hospital-acquired pneumonia in Asian countries: first consensus report by the Asian HAP Working Group. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(4 Suppl):S83–S92. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anstey NM, Currie BJ, Withnall KM. Community-acquired Acinetobacter pneumonia in the Northern Territory of Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:83–91. doi: 10.1093/clinids/14.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeana C, Larson E, Sahni J, Bayuga SJ, Wu F, Della-Latta P. The epidemiology of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: does the community represent a reservoir? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24:275–279. doi: 10.1086/502209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho PL, Cheng VC, Chu CM. Antibiotic resistance in community-acquired pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and Acinetobacter baumannii. Chest. 2009;136:1119–1127. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]