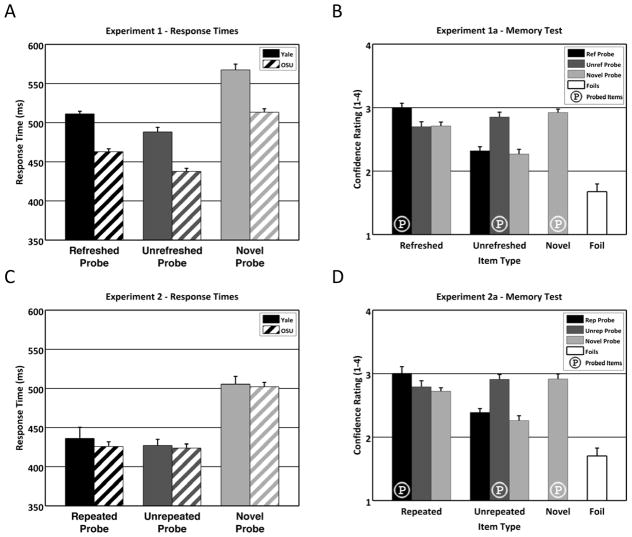

Figure 2. Results from Experiments 1 and 2.

A: Response times for Experiment 1a (Yale) and 1b (OSU). Participants were slower to respond to refreshed probes (1a: 511ms, 1b: 463ms) than unrefreshed probes (1a: 488ms, 1b: 438ms; an IOR-like effect) and slowest to respond to novel probes (1a: 567ms, 1b: 513ms). B: Memory test results for Experiment 1a. Participants indicated higher confidence in remembering all old items versus foils. Probed items (indicated with circled letter ‘P’) were remembered better than non-probed items, but most importantly, refreshed items (leftmost group of bars) were remembered better than unrefreshed items (second group of bars from left). C: Response times for Experiment 2a (Yale) and 2b (OSU). Participants were faster to respond to both repeated (2a: 436ms, 2b: 426ms) and unrepeated probes (2a: 427ms, 2b: 424ms) than novel probes (2a: 505ms, 2b: 502ms), but did not differ in their response times to repeated versus unrepeated probes. D: Memory test results for Experiment 2a. Despite the lack of a response time difference between repeated and unrepeated probes in Experiment 2, the memory test showed the same pattern of results as in Experiment 1a, in particular better memory for repeated (leftmost group of bars) than unrepeated items (second group of bars from left). Error bars in all panels were generated using Morey’s (2008) correction to Cousineau’s (2005) method for creating intuition-fitting error bars for within-subjects comparisons.