Abstract

Background

Depression and anxiety are prevalent and undertreated in patients receiving hospice care. Standard antidepressants do not work rapidly or often enough to benefit most of these patients. Ketamine has many properties that make it an interesting candidate for rapidly treating depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care. To test this hypothesis, a 28-day, open-label, proof-of-concept trial of daily oral ketamine administration was conducted in order to evaluate the tolerability, potential efficacy, and time to potential efficacy in treating depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care.

Methods

In this open-label study, 14 subjects with symptoms of depression or depression mixed with anxiety warranting psychopharmacological intervention received daily oral doses of ketamine hydrochloride (0.5 mg/kg) over a 28-day period. The primary outcome measure was the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which was used to rate overall depression and anxiety symptoms at baseline, and on days 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28.

Results

Over the 28-day trial there was significant improvement in both depressive symptoms (F5,35=8.03, p=0.002, η2=0.534) and symptoms of anxiety (F5,35=14.275, p<0.001, η2=0.67) for the eight subjects that completed the trial. One hundred percent of subjects completing the trial responded to ketamine for both anxiety and depression. A significant response in depressive symptoms occurred by day 14 for depression (mean Δ=3.5, d=1.14, 95% CI=1.09–5.9, p=0.01) and day 3 for anxiety (mean Δ=2.4, d=0.67, 95% CI=1.0–3.7, p=0.004). These improvements remained significant through day 28 for both depression (mean Δ=4.0, d=1.34, 95% CI=2.3–5.9, p=0.001) and anxiety (mean Δ=6.09, d=1.34, 95% CI=3.6–8.6, p<0.001). Side effects were rare, the most common being diarrhea, trouble sleeping, and trouble sitting still.

Conclusions

Patients who received daily oral ketamine experienced a robust antidepressant and anxiolytic response with few adverse events. The response rate for depression is similar to those found with IV ketamine; however, the time to response is more protracted. The findings of the potential efficacy of oral ketamine for depression and the response of anxiety symptoms are novel. Further investigation with randomized, controlled clinical trials is necessary to firmly establish the efficacy and safety of oral ketamine for the treatment of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care or other subject populations.

Introduction

Palliative care “aims to relieve suffering and improve quality of life throughout the illness and bereavement experience, so that patients and families can realize their full potential to live even when they are dying.”1 Untreated psychiatric symptoms or syndromes, as sequelae of advanced, life-threatening illness or as preexisting conditions, stand in the way of this therapeutic aim.

Psychiatric symptoms are prevalent in patients receiving hospice care. Up to 42% of hospice patients have symptoms of depression and up to 70% have symptoms of anxiety.2–4 Depression and anxiety are frequently undertreated in these patients. Untreated psychiatric symptoms are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, even in this population of patients.5 When untreated, these symptoms can also interfere with a patient's capacity to make decisions, understand their current medical situation, interact with caregivers, or ability to reach final goals.6 Anxiety and depression may also severely impact quality of life2,7 and are risk factors for suicidal behavior,8 especially in the elderly.9–12

Current standard pharmacologic treatments for depression in this population consist of the usual armamentarium of more than 24 antidepressants with at least 7 different mechanisms of action.13 Many of these are also indicated for anxiety, as are other medications, all of which have significant associated risks.14 An appropriate standard antidepressant trial is considered four to six weeks, and multiple trials are frequently necessary.15,16 As the average time patients receive hospice care in the United States is less than 10 weeks and the median is less than 3 weeks,17 current standards for antidepressant trials do not adequately address the needs of hospice patients suffering from depression and anxiety.

There is a growing body of literature supporting the rapid treatment of depressive symptoms, including suicidal ideation, with intravenous (IV) ketamine.18–31 Other than two case reports,32–34 no studies to date have examined ketamine's role in treating depression or anxiety in the hospice population. To our knowledge, no investigations of depression treatment for any population have been carried out with oral ketamine, and only a couple investigations of ketamine have assessed symptoms of anxiety.30,31

Ketamine is an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist and is commonly used as an anesthetic agent. In subanesthetic doses it can also be given as an adjuvant to opiates for the treatment of cancer pain, particularly when opiates alone are ineffective.35–42 In addition to being a potent NMDA receptor channel blocker, ketamine has other actions, which may contribute to its analgesic and antidepressant effects. These include its interactions with other calcium and sodium channels, cholinergic transmission, noradrenergic and serotonergic reuptake inhibition, glutamate transmission, synapse formation, and μ, δ,  , opioid-like effects.43–46 Oral ketamine undergoes extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism mainly to norketamine (via CYP3A4).47,48 Norketamine is about one-third as potent as parenteral ketamine for anesthesia; however, it is equipotent as an analgesic. The maximum blood concentration of norketamine is actually greater after oral administration than after parenteral administration.49 Ketamine has a wide therapeutic range, making overdose difficult. Notably, anesthesia dosing is significantly higher than analgesia and depression dosing. Ketamine does have the potential to be abused at higher dosing ranges.

, opioid-like effects.43–46 Oral ketamine undergoes extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism mainly to norketamine (via CYP3A4).47,48 Norketamine is about one-third as potent as parenteral ketamine for anesthesia; however, it is equipotent as an analgesic. The maximum blood concentration of norketamine is actually greater after oral administration than after parenteral administration.49 Ketamine has a wide therapeutic range, making overdose difficult. Notably, anesthesia dosing is significantly higher than analgesia and depression dosing. Ketamine does have the potential to be abused at higher dosing ranges.

Overall, ketamine has many properties that make it a good candidate for treating depression and anxiety, especially in patients receiving hospice care. It is inexpensive and easy to administer by multiple routes. It also has a rapid onset of action and minimal side effects when used at subanesthetic doses. Effectiveness and safety may improve with oral administration should ketamine's effects prove to be due, at least in part, to norketamine.50 Significant literature supports its safe use in hospice patients for other symptoms, including pain.36,37,40,41,51–56

Presented are data from a 28-day, open-label, proof-of-concept trial of daily oral ketamine administration with the objectives of evaluating and assessing the tolerability, potential efficacy, and time to potential efficacy in the treatment of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care.

Methods

Participants were male and female subjects, aged greater than 18 years, having a life limiting illness and receiving hospice care. Participants also had depressive symptomatology warranting psychopharmacological intervention, as determined by two clinicians. Subjects were required to have a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score of ≥15 or a HADS depression subscale score of ≥8 at screening and at the start of ketamine treatment. Subjects were studied as inpatients, outpatients, nursing home patients, or homecare patients receiving hospice care from San Diego Hospice and The Institute for Palliative Medicine, between February 2011 and April 2012.

Exclusion criteria included the presence of delirium; a mini-mental state score (MMSE) <24; symptoms of psychosis; history of intolerability, hypersensitivity, or allergy to ketamine; current effective antidepressant treatment; or current use of ketamine for depression or another symptom (e.g., neuropathic pain). While not exclusion criteria, caution was used in enrolling subjects with significant tachyarrhythmias; severe angina or myocardial ischemia; poorly controlled congestive heart failure; poorly controlled hypertension; poorly controlled hypo- or hyperthyroidism; current use of theophylline, memantine, or MAOIs; history of cerebral aneurysms; glaucoma; any intracranial mass; use of medications with significant drug-drug interactions with ketamine; or increased intracranial pressure. Female subjects could not be pregnant or nursing. The study was approved by San Diego Hospice and The Institute for Palliative Medicine institutional review board. All subjects provided written informed consent and needed to maintain capacity for consent to remain in the study.

Study design

This single center, 28-day, open-label, proof-of-concept trial was conducted to assess the potential efficacy and safety of daily oral ketamine administration for the treatment of symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care. Subjects were allowed to take concomitant psychiatric medications.

Subjects received a nightly oral (PO) dose of ketamine (10 mg/ml up to a final dose of 0.5 mg/kg in the same volume of cherry syrup) using the open-label design. This dose was based on the equianalgesic potency of oral and parenteral ketamine.49 Patients were removed from the study if they had intolerable side effects; and—for ethical reasons in this population with short prognoses—they had the choice to exit the study if there was not a 30% reduction in symptoms by day 14.

Outcome measures

Subjects were assessed with standardized instruments on day 0 (baseline) and days 3 (to capture any rapid effects), 7, 14, 21, and 28. The primary outcomes for this trial were symptoms of anxiety and depression as measured by the HADS.57,58 Secondary outcomes included (1) cognition (as measured by the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE));59 (2) pain (as measured by a pain visual analog scale (Pain VAS) derived from the Brief Pain Inventory Short Form (BPI-SF));60 (3) adverse events (as measured by an Adverse Symptom Checklist (ASC) and Suicide Risk Assessment (SRA) derived from the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview English Version 5.0.0 (M.I.N.I. PLUS));61 (4) quality of life (McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL);62–64 and (5) functional status (Karnofsky Performance Status Scale (KPSS)).60 In addition, clinical assessments were made by trained clinicians on days 14 and 28 of the study. Patient ratings were performed by two research nurses and a physician who were trained to a high level of interrater reliability (>0.90), which was checked on a regular basis.

For adverse events, five categories of symptoms were identified from a 33-adverse-symptoms checklist. These categories were cardiorespiratory symptoms (4 items); gastrointestinal symptoms (5 items); neurological symptoms (8 items); psychiatric/behavioral symptoms (13 items); and other (3 items, that included ophthalmic, musculoskeletal, and dermatologic symptoms). Ratings on the individual items were 0 (none), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe).

Analyses

After confirming the data were normally distributed, the effect of ketamine over time was analyzed with repeated measures ANOVAs, with time being a within-subjects factor and depression and anxiety scores as the dependent variables. Response is typically defined as a clinically meaningful reduction in symptoms, which we found at a 30% reduction in HADS scores based on clinical examination by qualified mental health experts, with a particular focus of the exam on symptoms of anxiety and depression. Significance was evaluated at the α=0.05 level, two tailed, after Greenhouse-Geisser corrections. Pairwise comparisons of the study day assessments to baseline for significant main effects and interactions were performed with Sidak corrections for multiple comparisons.65

For each subject, severity of each symptom on the adverse-symptom checklist was summed for each category, and category severity was averaged across subjects on each assessment day. In addition, frequency of moderate or greater changes in somatic symptoms for each assessment day was tabulated.

Results

Patients

Sixteen subjects consented to the study, and 14 subjects were started on the medication. One subject dropped out after day 3 due to rapid decline in condition unrelated to ketamine treatment; four subjects withdrew from the study after day 14 due to no response to ketamine; and one subject withdrew after day 21 due to mental status changes unrelated to the ketamine treatment, leaving eight subjects who completed the study and were included in the analyses. Demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, Location Where Treated, and Primary Hospice Diagnosis of Patients Completing the Studya

| Count | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White/Hispanic | 1 | 12 |

| White/non-Hispanic | 7 | 88 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 7 | 88 |

| Male | 1 | 12 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 2 | 25 |

| Single | 2 | 25 |

| Widowed | 2 | 25 |

| Divorced | 2 | 25 |

| Location | ||

| Home | 7 | 88 |

| Skilled nursing facility | 1 | 12 |

| Primary Hospice Diagnosis | ||

| Cardiovascular | 1 | 12 |

| Hepatic | 1 | 12 |

| Neoplastic | 3 | 40 |

| Pulmonary | 1 | 12 |

| Renal | 1 | 12 |

| Other | 1 | 12 |

Age of participants: Mean=63, SD=18, range 36 to 88.

Responders and nonresponders

Of the eight subjects completing the study, all (100%) showed a 30% or greater improvement in both HADS anxiety and depression scores. The six patients (43%) who withdrew from the study all showed a 30% or greater improvement on the HADS anxiety subscale and none (0%) showed an improvement on the depression subscale.

Potential efficacy for anxiety and depression

Anxiety

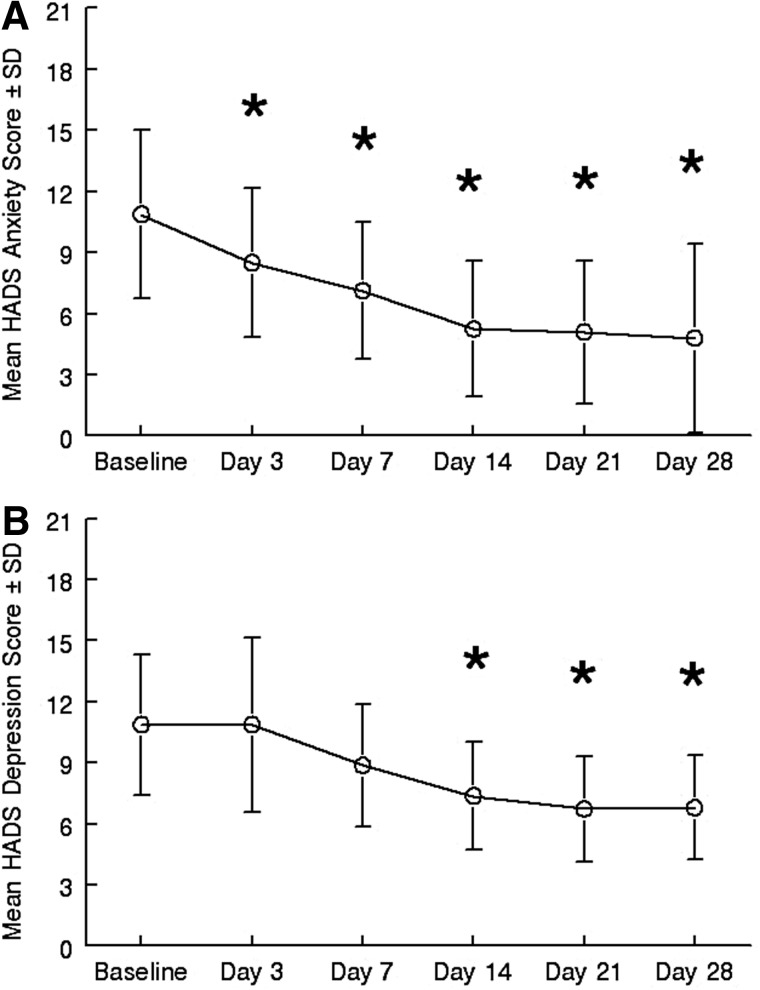

A repeated measures ANOVA on the HADS demonstrated a significant effect of time on anxiety, with anxiety symptoms decreasing significantly in all eight completers during treatment (F5,35=14.275, p<0.001, η2=0.67). Corrected posthoc pairwise comparisons to baseline found that day 3 (mean Δ=2.4, d=0.67, 95% CI=1.0–3.7, p=0.004); day 7 (mean Δ=3.7, d=1.1, 95% CI=2.4–5.1, p<0.001); day 14 (mean Δ 5.7, d=1.13, 95% CI=3.5–5.6, p=0.012); day 21 (mean Δ 5.7, d=1.36, 95% CI=3.6–7.9, p<0.001); and day 28 (mean Δ 6.09, d=1.34, 95% CI=3.6–8.6, p<0.001) scores were significantly lower than baseline (see Figure 1A). Clinical exams by mental health experts confirmed significant improvements in anxiety symptoms in all completers on days 14 and 28 of the trial.

FIG. 1.

Mean±SD of (A) HADS anxiety and (B) HADS depression scores at baseline and in response to treatment with oral ketamine over time. *Indicates that the score was significantly (p<0.05) lower than baseline.

Depression

A repeated measures ANOVA on the HADS demonstrated a significant effect of time on depressive symptoms as well, with depression scores also decreasing significantly over the course of the study for all eight completers (F5,35=8.03, p=0.002, η2=0.534). Corrected posthoc pairwise comparisons to baseline found that day 14 (mean Δ=3.5, d=1.14, 95% CI=1.09–5.90, p=0.01); day 21 (mean Δ=4.1, d=1.364, 95% CI=2.0–6.2, p=0.002); and day 28 (mean Δ=4, d=1.34, 95% CI=2.3–5.9, p=0.001) scores were significantly lower than baseline (see Figure 1B). Clinical exams by mental health experts confirmed significant improvements in depressive symptoms in all completers on days 14 and 28 of the trial.

Time to response

The mean (±SD) time to response for anxiety symptoms was 8.6±6 days (n=8, median=7). The mean (±SD) time to response for depressive symptoms was 14.4±19.1 days (n=8, median=10.5). All subjects maintained this response through day 28 for both measures.

Secondary outcome measures

No changes were found in pain levels (not all subjects had pain), functional status, cognition, suicide risk, or quality of life.

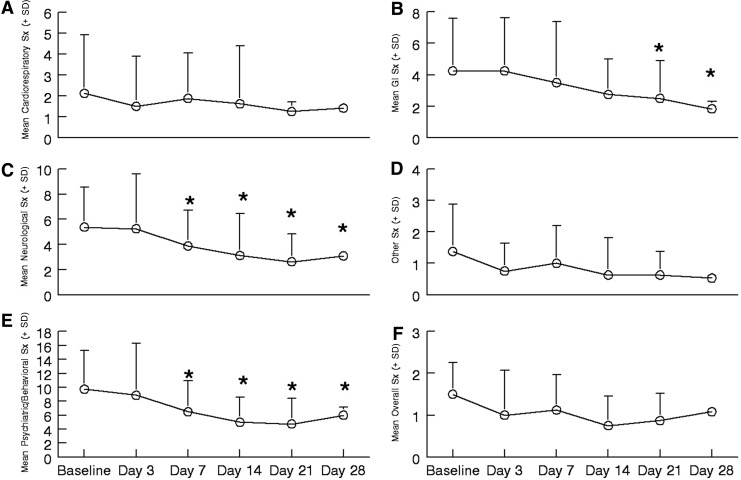

Adverse events

No vital sign changes (see Table 2) and no serious adverse events due to ketamine occurred during the study. Mild increases in complaints about diarrhea, trouble sleeping, and trouble sitting still occurred in 12.5% of the sample (one subject for each). As shown in Figure 2, on average, somatic symptom severity decreased significantly in three categories compared to baseline, and were unchanged in the others. Neurological (p=0.022) and psychiatric/behavioral (p=0.002) categories showed a significant decrease in reported symptoms starting day 7 (see Figure 2 panels C and E), whereas gastrointestinal (p=0.044) symptoms decreased significantly by day 21. Decreases in symptom severity were sustained until completion of the study.

Table 2.

Mean (±SD) for Height, Weight, and Vital Signs on Study Assessment Days

| |

Baseline |

Day 3 |

Day 7 |

Day 14 |

Day 21 |

Day 28 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| BMI | 25.4 | 11.6 | 25.6 | 11.5 | 25.6 | 11.5 | 25.6 | 11.5 | 25.6 | 11.5 | 25.3 | 12.6 |

| Systolic BP | 122.6 | 21.6 | 121.1 | 21.6 | 119.9 | 17.8 | 121.0 | 20.5 | 116.3 | 17.9 | 133.7 | 24.0 |

| Diastolic BP | 75.3 | 8.2 | 66.4 | 4.7 | 69.3 | 7.8 | 68.3 | 9.7 | 68.4 | 8.1 | 74.5 | 13.5 |

| Pulse | 82.0 | 4.3 | 85.0 | 11.8 | 82.0 | 11.5 | 81.4 | 18.2 | 80.0 | 19.6 | 87.3 | 11.3 |

| Respiration | 17.4 | 2.5 | 17.7 | 1.8 | 17.4 | 1.5 | 15.7 | 2.1 | 14.8 | 3.0 | 17.7 | 3.7 |

FIG. 2.

Mean±SD of the five categories' symptom severity and an overall report of adverse symptoms reported during the study. In all panels * indicates reported symptoms are significantly (p<0.05) less than baseline. (A) Cardiovascular and respiratory symptoms (Sx). (B) Gastrointestinal symptoms. (C) Neurological symptoms. (D) Other symptoms. (E) Psychiatric/behavioral symptoms. (F) Overall sense of adverse symptoms.

Discussion

This 28-day open-label proof-of-concept trial of daily oral ketamine administration is the first step in evaluating tolerability, potential efficacy, and time to potential efficacy of daily oral ketamine for treating symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care. To our knowledge, this is the first clinical trial, albeit open-label, wherein ketamine was used to treat symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care. It is also the first trial to demonstrate the use of oral ketamine administration targeting depression and to demonstrate ketamine's anxiolytic effects. It also adds to existing published data regarding use of repeated ketamine dosing.

A significant improvement in depressive symptoms occurred with oral ketamine at a similar response rate (57%) to other published cases and studies (14%–85%), all of which utilized IV administration in patients with treatment resistant depression that were otherwise healthy;66 however, unlike what was previously demonstrated, this effect was more protracted (occurring over weeks rather than in minutes) and more sustained than found with IV infusions of ketamine (>2 weeks). A significant novel finding was a decrease in symptoms of anxiety in 100% of the cases. Few adverse events or increases in somatic symptoms were noted, as has been the case in previously reported trials; in fact, in this study, all somatic symptoms significantly decreased. Also of note, no significant changes were noted in vital signs, cognition, suicide risk, or evidence of delirium. Interestingly, no changes in pain scores were found either, indicating that improvements in mood and anxiety were independent of the possible effects of ketamine on pain. However, not all subjects in the study had symptoms of pain to begin with. It was disappointing to not find changes in functional status or quality of life; however, given the small sample size and the limitations of the scales used to measure these important aspects, positive findings in these domains may be borne out in larger trials. Furthermore, clinical examinations revealed large changes in quality of life and functional status, even though this was not evident by results from the standardized measures.

Some of the alternative findings versus IV administration may be due to 1) the oral dosing itself, which might provide similar antidepressant and anxiolytic effects and fewer adverse events than those of IV administration possibly due to first pass metabolism to norketamine or 2) due to differing bioavailablity via the different routes.50 The more protracted time to response is disappointing, especially in this population, where time is of the essence. Still, the response rate and time to response is better than with standard antidepressant therapy.15,16 In addition, the decreases in somatic symptoms are particularly interesting and important to this population that has significant medical illness and high symptom burden, as compared to subjects in other studies of ketamine for depression.

The positive findings with repeated oral dosing are very promising, as oral dosing is much more practical and less invasive than IV delivery. Placement of IV catheters requires skill, particularly in medically frail patients. Complications of catheters include malfunction, thrombosis, infection, and extravasation, all of which limit systemic access and increase the cost of care.67–69 Furthermore, patients often endure multiple failed attempts at placement due to difficult venous access, which is common in medically ill patients. In addition, IV catheter placement does not last for more than a few days. Utilizing an alternate route of administration of ketamine, such as the oral route, would be beneficial for all patients, especially those with serious medical illness. The ability to give repeated dosing and maintain a response over a long period of time is also of importance, which is more feasible with oral dosing. Perhaps a response may need to be induced with parenteral ketamine, which then could be maintained with oral dosing, though further study on route, dosing intervals, long-term efficacy, and side effects is needed.

With these positive preliminary findings of potential efficacy for symptoms of both depression and anxiety, decreased somatic symptoms, high response rates, and rapid response in comparison with standard antidepressants, come some limitations. This was an open-label trial and is subject to all of the inherent biases in such trials. Subjects had either symptoms of depression or symptoms of depression mixed with symptoms of anxiety of unclear etiology. Also, as is often the case in clinical trials of this nature, especially in a medically ill population, the sample size is small. Furthermore, the sample comes from a fairly heterogeneous population of subjects receiving hospice care who have high medical comorbidity and high somatic symptom burden. Lastly, these subjects were recruited from a single site and the findings may not be generalizable.

Despite its limitations, this open-label proof-of-concept trial suggests that daily oral ketamine may significantly decrease depressive and anxiety symptoms in patients receiving hospice care with few adverse events. Further investigations with randomized, controlled clinical trials are necessary to firmly establish the comparative effectiveness and safety of daily oral ketamine for the treatment of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care or other patient populations. Quick acting, safe, and effective depression and anxiety treatments are needed in this population if a high-quality end-of-life experience is to be achieved. Oral ketamine may be such an intervention.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist for any author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the support from the faculty and staff of San Diego Hospice and The Institute for Palliative Medicine, including Charles von Gunten and Tracy Johnson. Support was also provided from the pharmacy at San Diego Hospice, specifically from Betty Richardson, Michael Sohmer, and Rosene Pirrello. We also thank Dilip Jeste, Joel Dimsdale, Sid Zisook, and Barry Lebowitz for their helpful comments on the manuscript and ongoing mentorship. Special thanks to Steve Koh, Nathan Fairman, and Jeremy Hirst for help with data collection, as well as J. S. Tanas. This work was supported, in part, by the National Institute of Mental Health K23MH091176 (Scott A. Irwin); a National Palliative Care Research Center Career Development Grant (Scott A. Irwin); and by donations from the generous benefactors of the education and research programs at San Diego Hospice and The Institute for Palliative Medicine.

References

- 1.Ferris FD. Balfour HM. Bowen K. Farley J. Hardwick M. Lamontagne C. Lundy M. Syme A. West P. A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson KG. Chochinov HM. de Faye BJ. Breitbart W. Diagnosis and Management of Depression in Palliative Care. In: Chochinov HM, editor; Breitbart W, editor. Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- 3.NIH: National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Symptom Management in Cancer: Pain, Depression, and Fatigue, July 15–17, 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;2004:9–16. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/djg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson KG. Chochinov HM. Skirko MG. Allard P. Chary S. Gagnon PR. Macmillan K. De Luca M. O'Shea F. Kuhl D. Fainsinger RL. Clinch JJ. Depression and anxiety disorders in palliative cancer care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDaniel JS. Brown FW. Cole SA. Assessment of depression and grief reactions in the medically ill. In: Stoudemire A, editor; Fogel BS, editor; Greenberg DB, editor. Psychiatric Care of the Medical Patient. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- 6.King DA. Heisel MJ. Lyness JM. Assessment and psychological treatment of depression in older adults with terminal or life threatening illness. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2005:339–353. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiegel D. Bloom JR. Group therapy and hypnosis reduce metastatic breast carcinoma pain. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:333–339. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198308000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breitbart W. Rosenfeld B. Pessin H. Kaim M. Funesti-Esch J. Galietta M. Nelson CJ. Brescia R. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA. 2000;284:2907–2911. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conwell Y. Duberstein PR. Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:193–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01347-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexopoulos GS. Bruce ML. Hull J. Sirey JA. Kakuma T. Clinical determinants of suicidal ideation and behavior in geriatric depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1048–1053. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.11.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waern M. Rubenowitz E. Wilhelmson K. Predictors of suicide in the old elderly. Gerontology. 2003;49:328–334. doi: 10.1159/000071715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stahl SM. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008. p. 1117. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Irwin SA. Ferris FD. The opportunity for psychiatry in palliative care. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:713–724. doi: 10.1177/070674370805301103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trivedi MH. Rush AJ. Wisniewski SR. Nierenberg AA. Warden D. Ritz L. Norquist G. Howland RH. Lebowitz B. McGrath PJ. Shores-Wilson K. Biggs MM. Balasubramani GK. Fava M. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: Implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thase ME. Friedman ES. Biggs MM. Wisniewski SR. Trivedi MH. Luther JF. Fava M. Nierenberg AA. McGrath PJ. Warden D. Niederehe G. Hollon SD. Rush AJ. Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second-step treatments: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:739–752. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Facts, Figures: Hospice Care in America. Alexandria, VA: NHPCO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krystal JH. Ketamine and the potential role for rapid-acting antidepressant medications. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:215–216. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudoh A. Takahira Y. Katagai H. Takazawa T. Small-dose ketamine improves the postoperative state of depressed patients. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:114–118. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200207000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zarate CA., Jr. Singh JB. Carlson PJ. Brutsche NE. Ameli R. Luckenbaugh DA. Charney DS. Manji HK. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:856–864. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berman RM. Cappiello A. Anand A. Oren DA. Heninger GR. Charney DS. Krystal JH. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Correll GE. Futter GE. Two case studies of patients with major depressive disorder given low-dose (subanesthetic) ketamine infusions. Pain Med. 2006;7:92–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liebrenz M. Borgeat A. Leisinger R. Stohler R. Intravenous ketamine therapy in a patient with a treatment-resistant major depression. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007;137:234–236. doi: 10.4414/smw.2007.11852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liebrenz M. Stohler R. Borgeat A. Repeated intravenous ketamine therapy in a patient with treatment-resistant major depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007:1–4. doi: 10.1080/15622970701420481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.aan het Rot M. Collins KA. Murrough JW. Perez AM. Reich DL. Charney DS. Mathew SJ. Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phelps LE. Brutsche N. Moral JR. Luckenbaugh DA. Manji HK. Zarate CA., Jr. Family history of alcohol dependence and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiazGranados N. Ibrahim LA. Brutsche NE. Ameli R. Henter ID. Luckenbaugh DA. Machado-Vieira R. Zarate CA., Jr. Rapid resolution of suicidal ideation after a single infusion of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1605–1611. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05327blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price RB. Nock MK. Charney DS. Mathew SJ. Effects of intravenous ketamine on explicit and implicit measures of suicidality in treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Larkin GL. Beautrais AL. A preliminary naturalistic study of low-dose ketamine for depression and suicide ideation in the emergency department. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:1127–1131. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zarate CA., Jr. Brutsche NE. Ibrahim L. Franco-Chaves J. Diazgranados N. Cravchik A. Selter J. Marquardt CA. Liberty V. Luckenbaugh DA. Replication of ketamine's antidepressant efficacy in bipolar depression: A randomized controlled add-on trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71:939–946. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim L. Diazgranados N. Franco-Chaves J. Brutsche N. Henter ID. Kronstein P. Moaddel R. Wainer I. Luckenbaugh DA. Manji HK. Zarate CA., Jr. Course of improvement in depressive symptoms to a single intravenous infusion of ketamine vs add-on riluzole: Results from a 4-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1526–1533. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irwin SA. Iglewicz A. Oral ketamine for the rapid treatment of depression and anxiety in patients receiving hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:903–908. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thangathurai D. Roby J. Roffey P. Treatment of resistant depression in patients with cancer with low doses of ketamine and desipramine. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:235. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stefanczyk-Sapieha L. Oneschuk D. Demas M. Intravenous ketamine "burst" for refractory depression in a patient with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1268–1271. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mercadante S. Ketamine in cancer pain: An update. Palliat Med. 1996;10:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mercadante S. Arcuri E. Ferrera P. Villari P. Mangione S. Alternative treatments of breakthrough pain in patients receiving spinal analgesics for cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mercadante S. Arcuri E. Tirelli W. Casuccio A. Analgesic effect of intravenous ketamine in cancer patients on morphine therapy: A randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover, double-dose study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:246–252. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mercadante S. Villari P. Ferrera P. Burst ketamine to reverse opioid tolerance in cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:302–305. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(03)00047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lauretti GR. Gomes JM. Reis MP. Pereira NL. Low doses of epidural ketamine or neostigmine, but not midazolam, improve morphine analgesia in epidural terminal cancer pain therapy. J Clin Anesth. 1999;11:663–668. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(99)00122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lauretti GR. Lima IC. Reis MP. Prado WA. Pereira NL. Oral ketamine and transdermal nitroglycerin as analgesic adjuvants to oral morphine therapy for cancer pain management. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1528–1533. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199906000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lossignol DA. Obiols-Portis M. Body JJ. Successful use of ketamine for intractable cancer pain. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:188–193. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0684-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson K. Ashby M. Martin P. Pisasale M. Brumley D. Hayes B. "Burst" ketamine for refractory cancer pain: An open-label audit of 39 patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:834–842. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meller ST. Ketamine: Relief from chronic pain through actions at the NMDA receptor? Pain. 1996;68:435–436. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maeng S. Zarate CA., Jr. Du J. Schloesser RJ. McCammon J. Chen G. Manji HK. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: Role of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptors. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:349–352. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li N. Lee B. Liu RJ. Banasr M. Dwyer JM. Iwata M. Li XY. Aghajanian G. Duman RS. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science. 2010;329:959–964. doi: 10.1126/science.1190287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murrough JW. Ketamine as a novel antidepressant: From synapse to behavior. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:303–309. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hijazi Y. Boulieu R. Contribution of CYP3A4, CYP2B6, and CYP2C9 isoforms to N-demethylation of ketamine in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2002;30:853–858. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.7.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hijazi Y. Boulieu R. Protein binding of ketamine and its active metabolites to human serum. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;58:37–40. doi: 10.1007/s00228-002-0439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clements JA. Nimmo WS. Grant IS. Bioavailability, pharmacokinetics, and analgesic activity of ketamine in humans. J Pharm Sci. 1982;71:539–542. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600710516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodman LS. Gilman A. Brunton LL. Lazo JS. Parker KL. Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006. 2021. p. xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carr DB. Goudas LC. Denman WT. Brookoff D. Staats PS. Brennen L. Green G. Albin R. Hamilton D. Rogers MC. Firestone L. Lavin PT. Mermelstein F. Safety and efficacy of intranasal ketamine for the treatment of breakthrough pain in patients with chronic pain: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Pain. 2004;108:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kannan TR. Saxena A. Bhatnagar S. Barry A. Oral ketamine as an adjuvant to oral morphine for neuropathic pain in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:60–65. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Subramaniam K. Subramaniam B. Steinbrook RA. Ketamine as adjuvant analgesic to opioids: A quantitative and qualitative systematic review. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:482–495. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000118109.12855.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fitzgibbon EJ. Hall P. Schroder C. Seely J. Viola R. Low dose ketamine as an analgesic adjuvant in difficult pain syndromes: A strategy for conversion from parenteral to oral ketamine. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:165–170. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00393-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fine PG. Low-dose ketamine in the management of opioid nonresponsive terminal cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;17:296–300. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(98)00144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clark JL. Kalan GE. Effective treatment of severe cancer pain of the head using low-dose ketamine in an opioid-tolerant patient. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1995;10:310–314. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(95)00010-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zigmond AS. Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lloyd-Williams M. Friedman T. Rudd N. An analysis of the validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale as a screening tool in patients with advanced metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:990–996. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Folstein MF. Folstein SE. McHugh PR. Fanjiang G. Mini-Mental State Examination User's Guide. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mor V. Laliberte L. Morris JN. Wiemann M. The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale: An examination of its reliability and validity in a research setting. Cancer. 1984;53:2002–2007. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840501)53:9<2002::aid-cncr2820530933>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sheehan DV. Lecrubier Y. Sheehan KH. Amorim P. Janavs J. Weiller E. Hergueta T. Baker R. Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen SR. Mount BM. Strobel MG. Bui F. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire, a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease: A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med. 1995;9:207–219. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cohen SR. Mount BM. Bruera E. Provost M. Rowe J. Tong K. Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the palliative care setting: A multi-centre Canadian study demonstrating the importance of the existential domain. Palliat Med. 1997;11:3–20. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bruley DK. Beyond reliability and validity: Analysis of selected quality-of-life instruments for use in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 1999;2:299–309. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1999.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ludbrook J. On making multiple comparisons in clinical and experimental pharmacology and physiology. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1991;18:379–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1991.tb01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.aan Het Rot M. Zarate CA., Jr. Charney DS. Mathew SJ. Ketamine for depression: Where do we go from here? Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kurul S. Saip P. Aydin T. Totally implantable venous-access ports: Local problems and extravasation injury. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:684–692. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00905-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Monreal M. Davant E. Thrombotic complications of central venous catheters in cancer patients. Acta Haematol. 2001;106:69–72. doi: 10.1159/000046591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sasson M. Shvartzman P. Hypodermoclysis: An alternative infusion technique. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1575–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]