Figure 1.

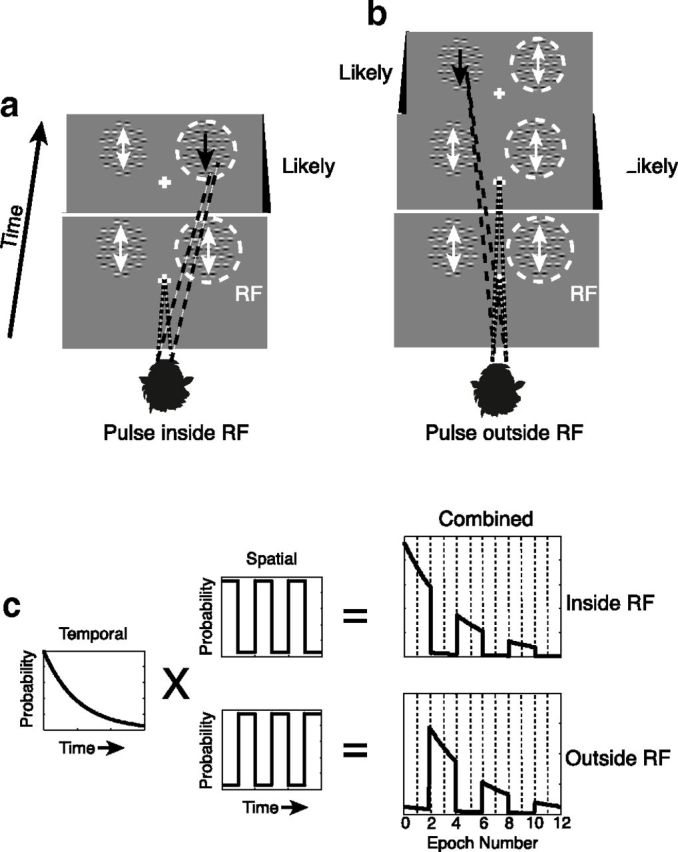

Motion pulse detection for two example trials. Animals were required to fixate on a central point while monitoring two peripherally located arrays of Gabors. One of these arrays was centered on the RF (dashed circle) of the neuron under study, whereas the other was located across the vertical meridian. At both locations, motion noise (white arrows) was presented by randomly and independently shifting the phases of the sine waves within the Gabors. A brief motion pulse was defined by consistently shifting the phases of all of the Gabors within one array in a direction consistent with the preferred direction of motion of the neuron under study (black arrows). Correct trials were defined by the monkeys breaking fixation and saccading to the location of the motion pulse immediately after its appearance. Pulse occurrence was random for every trial, but the statistics governing the timing and locations of pulses were fixed. Likely pulse location (a, b, black panels) alternated systematically over the duration of the trial. Two correct trials in which the pulse appeared at the likely location given its timing are illustrated. a, In the first trial, the monkey saccades to the array within the RF in response to motion pulse appearing within the first period of high likelihood. b, In the second trial, the monkey correctly saccades to the opposite array in response to a motion pulse appearing at that location during one of its periods of high likelihood. Statistics governing pulse likelihood were determined by multiplying the probability of pulse occurrence at a given time by the probability of it appearing at a given location (c). To analyze how the effects of attention changed with time, each pulse cycle was divided into four epochs so that the first two epochs were “Likely,” the second two, “Unlikely,” etc.