Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The incidence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) is traditionally high in remote areas of Canada with large Aboriginal populations. Northwestern Ontario is home to 28,000 First Nations people in more than 30 remote communities; rates of CA-MRSA are unknown.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the CA-MRSA rates and antibiotic susceptibilities in this region.

METHODS:

A five-year review of laboratory and patient CA-MRSA data and antibiotic susceptibility was undertaken.

RESULTS:

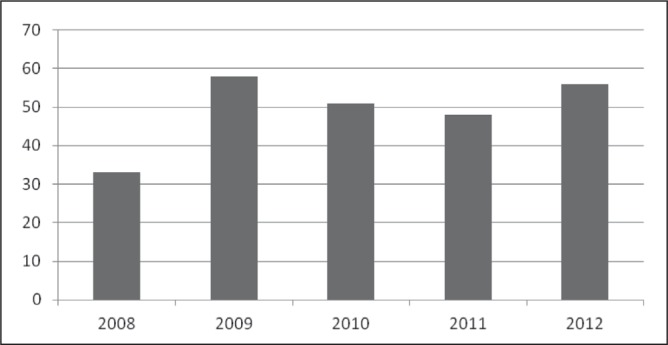

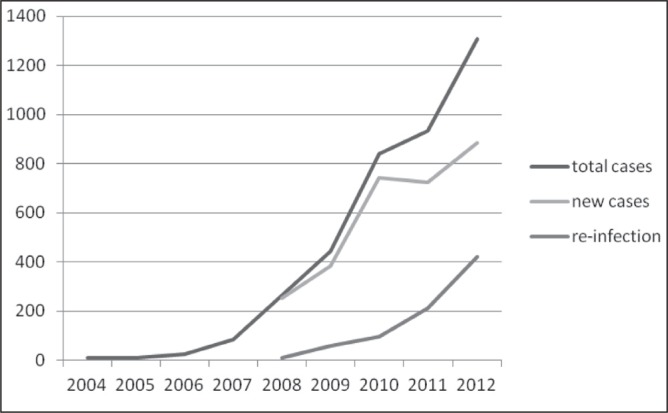

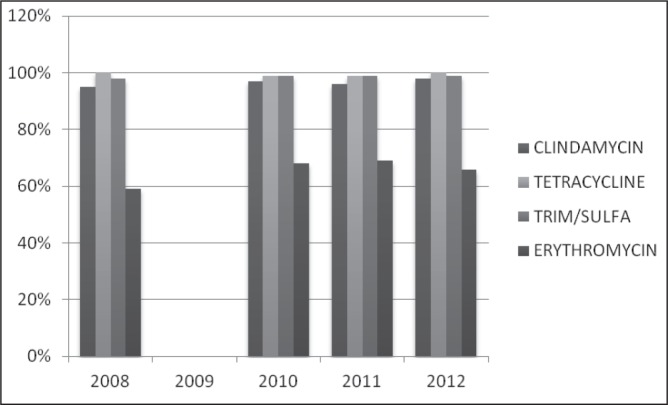

In 2012, 56% of S aureus isolates were CA-MRSA strains, an increase from 31% in 2008 (P=0.06). Reinfection rates have been increasing faster than new cases and, currrently, 25% of infections are reinfections. CA-MRSA isolates continue to be susceptible to many common antibiotics (nearly 100%), particularly trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin and tetracycline. Erythromycin susceptibility stands at 58%.

DISCUSSION:

Rates of CA-MRSA, as a percentage of all S aureus isolates, were higher than those reported in other primary care series. The infection rate per 100,000 is one the highest reported in Canada. Antibiotic susceptibilities were unchanged during the study period; the 99% susceptibility rate to clindamycin differs from a 2010 Vancouver (British Columbia) study that reported only a 79% susceptibility to this antibiotic.

CONCLUSION:

There are very high rates of CA-MRSA infections in northwestern Ontario. Disease surveillance and ongoing attention to antibiotic resistance is important in understanding the changing profile of MRSA infections. Social determinants of health, specifically improved housing and sanitation, remain important regional issues.

Keywords: Aboriginal, Antibiotic susceptibility, CA-MRSA, Northwest Ontario

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

L’incidence de Staphylococcus aureus résistant à la méthicilline d’origine non nosocomiale (SARM-ONN) est généralement élevée dans les régions éloignées du Canada aux fortes populations autochtones. Ainsi, 28 000 membres des Premières nations habitent dans plus de 30 communautés éloignées du nord-ouest de l’Ontario. On n’y connaît pas le taux de SARM-ONN.

OBJECTIF :

Déterminer le taux de SARM-ONN et les susceptibilités aux antibiotiques dans cette région.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Les chercheurs ont effectué une analyse quinquennale des données de laboratoire et des données des patients à l’égard du SARM-ONN ainsi que de leur susceptibilité aux antibiotiques.

RÉSULTATS :

En 2012, 56 % des isolats de S aureus étaient des souches de SARM-ONN, soit une augmentation par rapport aux 31 % de 2008 (P=0,06). Le taux de réinfection augmentait plus rapidement que le taux de nouveaux cas : 25 % des infections sont désormais des réinfections. Les isolats de SARM-ONN continuent d’être susceptibles à de nombreux antibiotiques courants (près de 100 %), notamment le triméthoprim-sulfaméthoxazole, la clindamycine et la tétracycline. La susceptibilité à l’érythromycine est de 58 %.

EXPOSÉ :

Le taux de SAMR-ONN, à titre de pourcentage de tous les isolats de S aureus, était plus élevé que celui déclaré dans d’autres séries de soins de première ligne. Le taux d’infection sur 100 000 habitants est l’un des plus élevés à être signalé au Canada. Les susceptibilités aux antibiotiques demeuraient inchangées pendant la période de l’étude. Le taux de susceptibilité de 99 % à la clindamycine diffère de celui de seulement 79 % obtenu dans une étude de 2010 menée à Vancouver, en Colombie-Britannique.

CONCLUSION :

Les chercheurs ont constaté un taux très élevé d’infections par le SARM-ONN au nord-ouest de l’Ontario. Il est important de surveiller la maladie et de demeurer attentif à l’antibiorésistance pour comprendre l’évolution du profil des infections par le SARM. Les déterminants sociaux de la santé, particulièrement l’amélioration des logements et des mesures d’assainissement, continuent de représenter d’importants problèmes régionaux.

The incidence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) has traditionally been high in remote areas of Canada with large Aboriginal populations (1–11). S aureus infections are increasingly found to be CA-MRSA, rendering beta-lactam therapy ineffective (12–14).

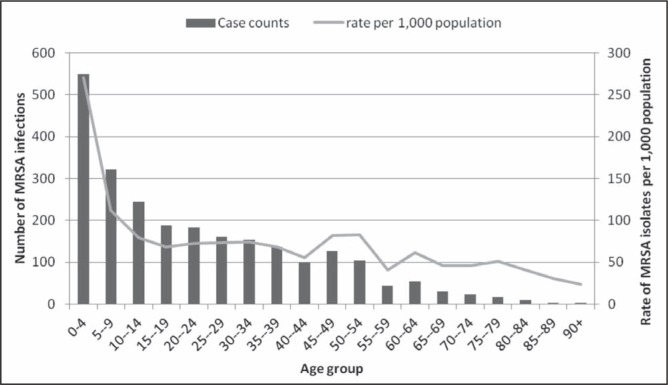

In northern Saskatchewan, 51% of Staphylococcus infections are CA-MRSA (2); in southern Manitoba, the rate is 40% (5). These infections most often affect children <10 years of age (30.4% of all CA-MRSA infections in northern Saskatchewan) and typically result in soft tissue infections (2). Associated risk factors for such high rates in these populations include overcrowding, inadequate housing and poor sanitation (1).

The purpose of the present study was to document the incidence of CA-MRSA in northwestern Ontario (2008 to 2012), examine the pattern of antibiotic resistance and review the seasonality of these infections.

METHODS

First-time infection rates from laboratory and infection control records from 2004 to 2012 were examined, with special attention to the recent five-year period in which data were most complete. Chart and laboratory records were retrospectively analyzed for 2986 CA-MRSA isolates; 2451 first-time infections were identified. Patient demographics, season of infection and antibiotic susceptibility were documented. The results of a 2010 six-month MRSA screening program of nasal swabs taken from all patients entering the hospital (emergency and inpatients) were also reviewed.

Statistics were analyzed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA), and linear regression was performed using SPSS version 17 (IBM Corporation, USA). Ethics approval was granted by the Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre Research Review Committee, Sioux Lookout, Ontario.

Participants

The region is home to 28,000 First Nations people (Ojibway and Cree), most of whom lived in 28 remote, fly-in communities with populations between 400 and 2400 in northwestern Ontario. Regional inpatient and outpatient bacteriology was processed through the Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre. Population age grouping was ascertained by combining Indian and Northern Affairs Canada and Ontario Local Health Integration Network information in 2011.

RESULTS

The laboratory recorded 2451 MRSA isolates (new infections) from January 2008 to July 2012. The majority of the isolates (82%) were from soft tissue infections. The number of tissue swabs remained constant over the time period of the study (6000 to 8000 annually).

In 2012, 56% of the S aureus isolates were CA-MRSA strains as determined by antibiograms, which was an increase from 31% in 2008 (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

Per cent of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates according to year of study

In 2010, a six-month in-hospital program screened registered inpatients or patients visiting the emergency department and found that 5% of nasal swabs tested positive for CA-MRSA. Other than this screening, all samples were taken for clinical management of infections.

The number of MRSA infections increased over the past five years and the increasing trend over the four years of complete data was borderline significant (P=0.06). Serious cases of sepsis and necrotizing pneumonia were rare but were also rising; one fatality from necrotizing pneumonia was recorded. Over the five-year period, skin and soft tissue infections increased by a factor of 2.4, while bacteremias, typically seen only once a year, were occuring almost monthly. The rate of CA-MRSA infection in the last year of complete data (2011) was 2482 per 100,000 population. Reinfections accounted for approximately 25% of infections (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

Number of new cases, reinfections and total cases of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection according to year of study

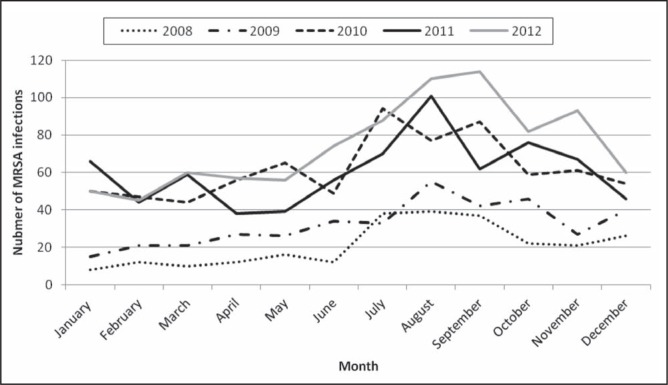

The infections were most commonly found in soft tissue and were more common in younger patients, with 35% of infections occurring in patients <10 years of age; the highest number of infections appeared in those zero to four years of age (Figure 3). Between 2008 and 2012, there was a seasonal trend to CA-MRSA infections, with the peak number of infections occurring in July and August (Figure 4).

Figure 3).

Number of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections and rates of MRSA isolates in Northwest Ontario between January 2006 and June 2012 according to age (years) (n=2447)

Figure 4).

Seasonal variation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections

CA-MRSA isolates were susceptible to many common antibiotics (nearly 100%), particularly trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin and tetracycline. Erythromycin susceptibility was 58% (Figure 5).

Figure 5).

Antibiotic sensitivity of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates (2009 data not available). TRIM/SULFA Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

DISCUSSION

The rates of CA-MRSA as a percentage of all S aureus isolates in the present study was higher than those reported in other primary care series (2,5,6,9,10,13). This may be due to the absence of running water in many of our regional communities, as well as inadequate housing (15). Our increasing reinfection rate may be a reflection of this reality because reinfections would more likely occur in an unchanged, high-risk environment. Additionally, the infection rate per 100,000 is one the highest reported in Canada and comparable with the 2011 northern Saskatchewan study (2), which showed a community range from 1460 infections per 100,000 to 4820 infections per 100,000.

Most of the infections in the present study were diganosed in soft tissue and this is consistent with most CA-MRSA studies (2). The reason for the high rate of reinfection in our study is not apparent. It is not clear whether these represent failure of therapy, persistent carriage or reinfection. We also identified a recent increase in bacteremia but it is too early to know whether this trend will continue.

Regarding seasonality, the number of infections increased during summer months when insect bites and perspiration are most prevalent in our region. Insect bites have been identified as an associated risk (40%) in a study by Golding et al (1).

Our regional antibiotic susceptibilities were unchanged during the study period. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline and clindamycin all remained effective antibiotic choices. This differs from a study conducted in Vancouver (British Columbia) hospitals in 2010 (16), which showed only a 79% susceptibility to clindamycin. We continue to prospectively track antibiotic resistance through our hospital laboratory system.

Limitations of our study include difficulties in manually accessing information records in different formats by different hospital departments and outside agencies, whose protocols changed during the study period. Some data were not present and are recorded as such. Other than site tissue swab, gathering clinical information was beyond the scope of the study.

CONCLUSION

There are high rates of CA-MRSA infections in northwestern Ontario. Ongoing disease surveillance is important, as is continued attention to antibiotic resistance and stewardship to understanding the changing profile of MRSA infections. Social determinants of health; specifically, improved housing and sanitation, remain issues in many communities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Golding G, Levett P, McDonald R, et al. A comparison of risk factors associated with community-associated methicillin resistant and susceptible Staphylococcus aureus infections in remote communities. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:730–7. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809991488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Golding G, Levett P, McDonald R, et al. High rates of Staphylococcus aureus USA400 infection in northern Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:722–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1704.100482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maguire G, Arthur A, Boustead P, Dwyer B, Currie B. Emerging epidemic of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in the Northern territory. Med J Aust. 1996;164:721–3. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb122270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wylie J, Nowicki D. Molecular epidemiology af community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Manitoba, Canada. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2830–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2830-2836.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd K, Holman R, Bruce M, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-associated hospitalizations among American Indian and Alaska native population. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1009–15. doi: 10.1086/605560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groom A, Wosley D, Naimi T, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a rural American Indian community. JAMA. 2001;286:1201–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.10.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David M, Rudolph K, Hennessy T, et al. MRSA USA300 at Alaska Native medical center, Anchorage, Alaska, USA, 2000–2006. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:105–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.110746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald M, Dougall A, Holt D, et al. Use of single-nucleotide polymorphism genotyping system to demonstrate the unique epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in remote Aboriginal communities. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3720–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00836-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tong S, Bishop E, Lilliebridge R, et al. Community-associated strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus in Indigneous northern Australia; epidemiology and outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1461–70. doi: 10.1086/598218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ofner-Agostini M, Simor A, Bryce E, McGeer A, Paton S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canadian Aboriginal people. Infection Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27:204–7. doi: 10.1086/500628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molaghan A. Changing epidemiology of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Br J Biomed Sci. 2011;68:171–3. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2011.11730345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nichol K, Adam H, Hussain Z, et al. Comparison of community-associated and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Canada: Results of the CANWARD 2007–2009 study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;69:320–5. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talan D, Krishnadansan A, Gorwitz R, et al. Comparison of Staphylococcus aureus from skin and soft-tissue infections in US emergency department patients, 2004 and 2008. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:144–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter J. First Nations housing shortage getting worse. CBC News. < www.cbc.ca/news/canada/.../tby-keewayin-housing-shortage.html> (Accessed September 4, 2012).

- 16.Al-Rawahi G, Reynolds S, Porter S, et al. Community-associated CMRSA-10 (USA300) is the predominant strain among methicillin-resistant Staphyloccus aureus strains causing skin and soft tissue infections in patients presenting to the emergency department of a Canadian tertiary care hospital. J Emerg Med. 2010;38:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]