Abstract

Three new cembrane-type diterpenoids, flexibilins A–C (1–3), along with a known cembrane, (−)-sandensolide (4), were isolated from the soft coral, Sinularia flexibilis. The structures of cembranes 1–4 were elucidated by spectroscopic methods. The structure of 4, including its absolute stereochemistry, was further confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. Cembrane 2 displayed a moderate inhibitory effect on the release of elastase by human neutrophils.

Keywords: cembrane, diterpenoid, Sinularia flexibilis, elastase

1. Introduction

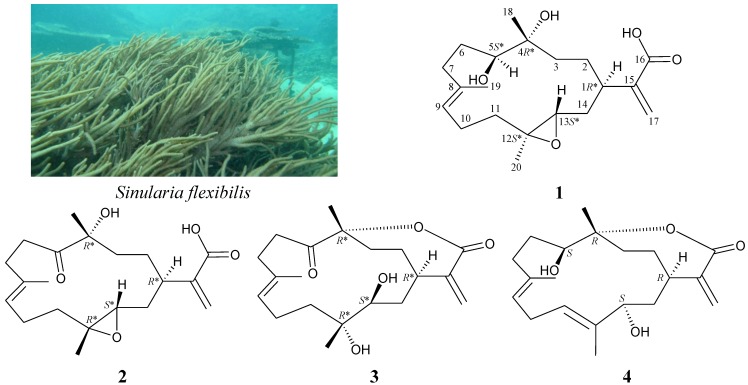

Octocorals, particularly, soft corals belonging to the genus Sinularia, have been demonstrated to be rich sources of bioactive natural products [1,2]. Previous chemical investigations on Sinularia flexibilis, an octocoral distributed widely in the tropical and subtropical waters of the Indo-Pacific Ocean, have yielded a series of interesting cembrane-type diterpenoids [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], and most of these compounds have been shown to possess various bioactivities, such as cytotoxic [4,6,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,20,21], anti-inflammatory [19,20], neuroprotective [19] and algicidal [9] effects. In continuation of our search for new substances from marine invertebrates collected from the waters of Taiwan, the octocoral Sinularia flexibilis (Quoy and Gaimard, 1833) was studied (Figure 1), as its organic extract was found to display meaningful signals in NMR studies. Three new cembrane-type diterpenoids, flexibilins A–C (1–3), and a known cembrane, (−)-sandensolide (4) [10,22,23], were isolated (Figure 1). In this paper, we reported the isolation, structure determination and bioactivity of cembranes 1–4.

Figure 1.

The soft coral, Sinularia flexibilis, and the structures of flexibilins A–C (1–3) and (−)-sandensolide (4).

2. Results and Discussion

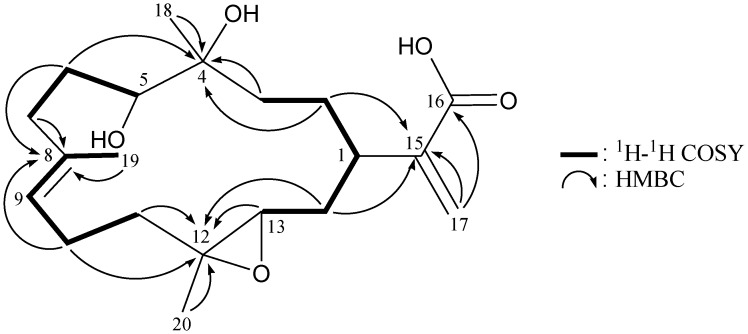

Flexibilin A (1) was obtained as yellowish oil, and its molecular formula, C20H32O5, was determined according to a pseudomolecular ion [M + Na]+ at m/z 375.2144 (calcd. for C20H32O5Na, 375.2147) identified by HRESIMS, as well as 13C NMR coupled with DEPT spectra (Table 1), which indicated that the double bond equivalence (DBE) of 1 was five. The IR spectrum of 1 revealed the presence of carboxylic acid, hydroxy and ester functionalities from absorptions at 3750–2400, 3419 and 1711 cm−1, respectively. The 13C NMR data of 1 showed the presence of 20 carbon signals in total, which were assigned by the assistance of the DEPT spectrum to three methyls, seven sp3 methylenes, three sp3 methines, two sp3 quaternary carbons, an sp2 methylene, an sp2 methine and three sp2 quaternary carbons. 13C NMR signals appearing at δC 170.8 (C-16), 142.7 (C-15) and 126.5 (CH2-17) and proton NMR signals appearing at δH 6.40 (1H, s) and 5.68 (1H, s) suggested the presence of a α-exomethylene-carboxylic acid moiety. The main carbon skeleton of 1 was elucidated by 1H–1H COSY and HMBC experiments (Table 1 and Figure 2). From the 1H–1H COSY spectrum of 1, it was possible to establish the separate spin systems of H-13/H2-14/H-1/H2-2/H2-3, H-5/H2-6/H2-7, H-9/H2-10/H2-11 and H-9/H3-19 (by allylic coupling). These data, together with the key HMBC correlations between protons and quaternary carbons, such as H2-2, H2-3, H2-6, H3-18/C-4; H2-6, H2-7, H2-10, H3-19/C-8; H2-10, H2-11, H-13, H2-14, H3-20/C-12; H2-2, H2-14, H2-17/C-15; and H2-17/C-16, permitted elucidation of the main carbon skeleton of 1. The tertiary methyls at C-4, C-8 and C-12 were confirmed by HMBC correlations between H3-18/C-3, -4, -5; H3-19/C-7, -8, -9; and H3-20/C-11, -12, -13. Thus, from the reported data, the skeleton of 1 was identified as a cembrane-type diterpenoid with two rings.

Table 1.

1H (500 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C (125 MHz, CDCl3) NMR data and 1H–1H COSY and HMBC correlations for cembrane 1.

| Position | δH (J in Hz) | δC, Multiple | 1H–1H COSY | HMBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.70 br s | 38.1, CH | H2-2, H2-14 | C-13 |

| 2 | 1.63 m; 1.52 m | 26.6, CH2 | H-1, H2-3 | C-1, -4, -14, -15 |

| 3 | 1.60 m; 1.53 m | 37.1, CH2 | H2-2 | C-2, -4, -5 |

| 4 | 74.8, C | |||

| 5 | 3.53 d (10.0) | 74.0, CH | H2-6 | C-6, -7, -18 |

| 6 | 1.71 m; 1.59 m | 28.6, CH2 | H-5, H2-7 | C-4, -5, -7, -8 |

| 7 | 2.21 m; 2.14 m | 33.7, CH2 | H2-6 | C-5, -6, -8, -9, -19 |

| 8 | 136.1, C | |||

| 9 | 5.11 dd (6.5, 6.5) | 122.7, CH | H2-10, H3-19 | C-7, -10, -11, -19 |

| 10 | 2.14 m | 23.1, CH2 | H-9, H2-11 | C-8, -9, -11, -12 |

| 11 | 2.01 ddd (14.0, 6.5, 3.0) | 37.5, CH2 | H2-10 | C-9, -10, -12, -20 |

| 1.42 ddd (14.0, 11.0, 3.0) | ||||

| 12 | 60.3, C | |||

| 13 | 2.87 dd (7.5, 5.5) | 61.2, CH | H2-14 | C-11, -12, -14 |

| 14 | 1.85 ddd (14.0, 10.0, 5.5); 1.61 m | 34.1, CH2 | H-1, H-13 | C-1, -2, -12, -13, -15 |

| 15 | 142.7, C | |||

| 16 | 170.8, C | |||

| 17 | 6.40 s; 5.68 s | 126.5, CH2 | C-1, -15, -16 | |

| 18 | 1.26 s | 24.7, CH3 | C-3, -4, -5 | |

| 19 | 1.67 s | 18.1, CH3 | H-9 | C-7, -8, -9 |

| 20 | 1.30 s | 17.1, CH3 | C-11, -12, -13 |

Figure 2.

1H–1H COSY and selected HMBC correlations (protons→quaternary carbons) for cembrane 1.

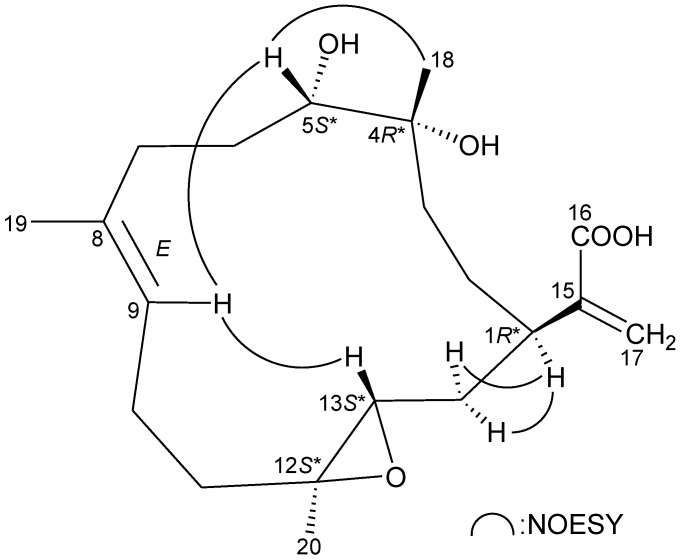

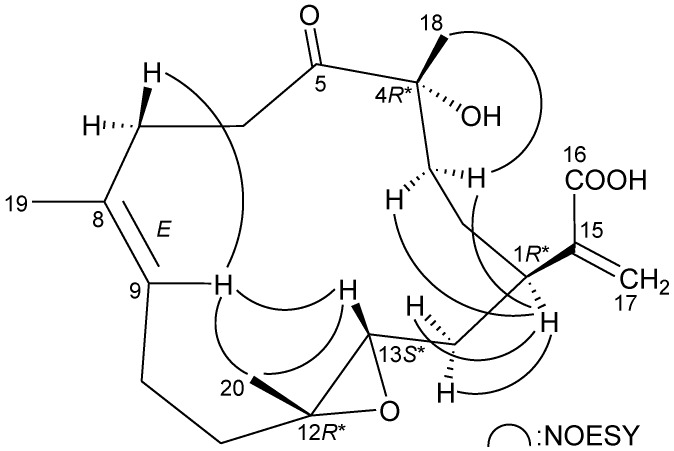

The relative configuration of 1 was elucidated from the interactions observed in a NOESY experiment, as shown in Figure 3. In the NOESY experiment of 1, H-1 was found to be correlated with H2-14, but not with H-13; this, plus, the lack of correlation between H-13 and H3-20 demonstrated that H-1, H-13 and Me-20 were α-, β- and α-oriented, respectively. Additionally, correlations between H-9/H-5 and H-9/H-13, and the absence of correlation between H-9/H3-19, reflected the E geometry of the double bond at C-8/9. From modeling analysis, H-9 was found to be close to H-5 and H-13, when H-5 and H-13 were β-oriented. H3-18 was found to be correlated with H-5, but not with H-1, indicating that the 4-hydroxy group was α-oriented. Based on the above findings, the structure of 1 was elucidated, and the chiral carbons of 1 were assigned as 1R*, 4R*, 5S*, 12S* and 13S*.

Figure 3.

Key NOESY correlations of 1.

The new cembrane diterpene, flexibilin B (2), had the molecular formula, C20H30O5, as deduced by HRESIMS (m/z calcd.: 373.1991; found 373.1989 [M + Na]+) (6° of unsaturation). The IR spectrum of 2 revealed the presence of carboxylic acid (νmax 3700–2400 cm−1), hydroxy (νmax 3447 cm−1) and carbonyl (νmax 1713 cm−1) moieties. From the 13C NMR and DEPT spectra of 2 (Table 2), a trisubstituted olefin (δC 134.5, C-8; 126.5, CH-9), a α-exomethylene-carboxylic acid (δC 171.3, C-16; 141.9, C-15; 126.2, CH2-17), a keto carbonyl (δC 213.6, C-5) and a trisubstituted epoxide (δC 60.8, C-12; 59.4, CH-13) were observed. The coupling information in the 1H–1H COSY spectrum of 2 enabled identification of the H-13/H2-14/H-1/H2-2/H2-3, H2-6/H2-7, H-9/H2-10/H2-11 and H-9/H3-19 (by allylic coupling) units. From these data, together with the results of an HMBC experiment for 2 (Table 2 and Figure 4), the molecular framework of 2 could be established.

Table 2.

1H (500 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C (125 MHz, CDCl3) NMR data and 1H–1H COSY and HMBC correlations for cembrane 2.

| Position | δH (J in Hz) | δC, Multiple | 1H–1H COSY | HMBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.75 m | 35.9, CH | H2-2, H2-14 | C-14 |

| 2 | 1.59 m; 1.41 m | 25.1, CH2 | H-1, H2-3 | C-4, -15 |

| 3 | 1.78 m; 1.52 m | 35.8, CH2 | H2-2 | C-4, -5, -18 |

| 4 | 78.9, C | |||

| 5 | 213.6, C | |||

| 6 | 2.70 m | 34.2, CH2 | H2-7 | C-5, -7, -8 |

| 7 | 2.55 m; 2.21 m | 31.5, CH2 | H2-6 | C-5, -6, -8, -9, -19 |

| 8 | 134.5, C | |||

| 9 | 5.13 dd (6.0, 6.0) | 126.5, CH | H2-10, H3-19 | C-7, -10, -11, -19 |

| 10 | 2.10 m; 2.01 m | 22.8, CH2 | H-9, H2-11 | C-8, -9, -11, -12 |

| 11 | 1.96 m; 1.56 m | 36.7, CH2 | H2-10 | C-9, -10, -12, -13 |

| 12 | 60.8, C | |||

| 13 | 2.79 dd (9.5, 4.0) | 59.4, CH | H2-14 | C-14 |

| 14 | 1.99 m; 1.42 m | 32.4, CH2 | H-1, H-13 | C-1, -12, -13, -15 |

| 15 | 141.9, C | |||

| 16 | 171.3, C | |||

| 17 | 6.42, s; 5.57 s | 126.2, CH2 | C-1, -15, -16 | |

| 18 | 1.35 s | 25.7, CH3 | C-3, -4, -5 | |

| 19 | 1.66 s | 17.0, CH3 | H-9 | C-7, -8, -9 |

| 20 | 1.27 s | 18.2, CH3 | C-11, -12, -13 |

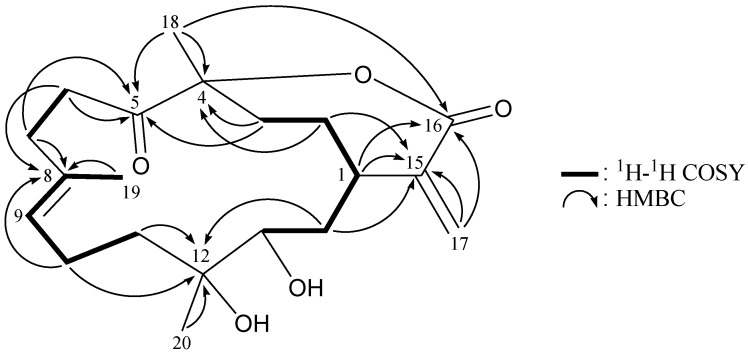

Figure 4.

1H–1H COSY and selected HMBC correlations (protons→quaternary carbons) for cembrane 2.

The relative stereochemistry of 2 was elucidated from the interactions observed in a NOESY experiment (Figure 5). Due to the α-orientation of H-1, the epoxy proton, H-13, was identified as being β-oriented, as no correlation was observed between H-1 and H-13. H-9 displayed correlations with H-13 and one of the C-7 methylene protons (δH 2.55), and there was a lack of correlation between H-9 and H3-19, which reflects the E geometry of the double bond between C-8/9. H3-20 showed correlations with H-9 and H-13, indicating that Me-20 is of a β-orientation at C-12. Furthermore, H-1 was found to be correlated with H2-3, and H3-18 exhibited a correlation with one of the C-3 methylene protons (δH 1.78), which indicated the β-orientation of Me-18 at C-4 by molecular modeling analysis. Based on the above information, the chiral carbons of cembrane 2 were assigned as 1R*, 4R*, 12R* and 13S*.

Figure 5.

Key NOESY correlations of 2.

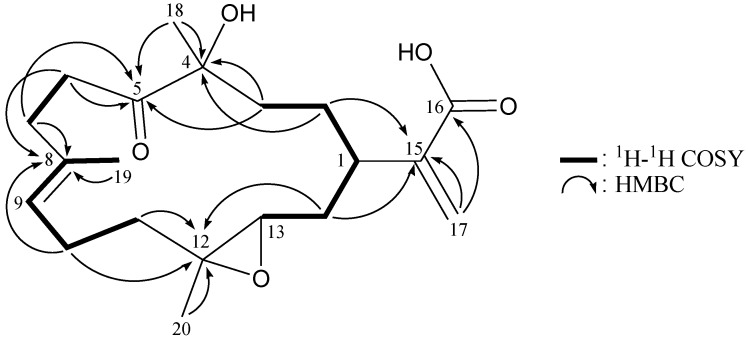

Flexibilin C (3) was obtained as a white powder. The molecular formula of 3 was established as C20H30O5 (6° of unsaturation) from a sodiated molecule at m/z 373 in the ESIMS spectrum and further supported by HRESIMS (m/z 373.1989, calcd. for C20H30O5Na, 373.1991). The IR spectrum of 3 exhibited the presence of hydroxy (νmax 3431 cm−1) and carbonyl (νmax 1711 cm−1) groups. From the 13C NMR data of 3 (Table 3), a suite of resonances at δC 168.0 (C-16), 143.3 (C-15), 126.0 (CH2-17), 90.0 (C-4), 37.4 (CH-1), 33.7 (CH2-3) and 29.7 (CH2-2) could be assigned to the α-exomethylene-ε-lactone moiety. Two additional unsaturated functionalities were indicated by 13C resonances at δC 209.3 (C-5), 134.7 (C-8) and 124.9 (CH-9), suggesting the presence of a keto carbonyl and a trisubstituted olefin. On the basis of the overall unsaturation data, 3 was concluded to be a diterpenoid molecule possessing two rings. The 1H NMR spectrum of 3 showed the presence of three methyl groups: two singlets at δH 1.27 and 1.49, representing the methyl groups on oxygenated quaternary carbons, respectively, and a vinyl methyl at δH 1.69. The 1H NMR coupling information in the 1H–1H COSY spectrum of 3 enabled identification of the H-13/H2-14/H-1/H2-2/H2-3, H2-6/H2-7, H-9/H2-10/H2-11 and H-9/H3-19 (by allylic coupling) units, which were assembled with the assistance of an HMBC experiment (Table 3 and Figure 6). The key HMBC correlations between protons and quaternary carbons of 3, such as H2-2, H2-3, H3-18/C-4; H2-3, H2-6, H2-7, H3-18/C-5; H2-6, H2-7, H2-10, H3-19/C-8; H2-10, H2-11, H2-14, H3-20/C-12; H-1, H2-2, H2-14, H2-17/C-15; and H-1, H2-17, H3-18/C-16, enabled establishment of the main carbon skeleton of 3. A vinyl methyl at C-8 was confirmed by the allylic coupling between H-9/H3-19 in the 1H–1H COSY spectrum and by the HMBC correlations between H3-19/C-7, -8, -9. The tertiary methyls at C-4 and C-12 were confirmed by the HMBC correlations between H3-18/C-3, -4, -5, and H3-20/C-11, -12, -13. H3-18 showed a long-range 4J-correlation with the ester carbonyl (δC 168.0, C-16) in the HMBC spectrum, which further supported the existence of the ε-lactone moiety in 3.

Table 3.

1H (500 MHz, CDCl3) and 13C (125 MHz, CDCl3) NMR data and 1H–1H COSY and HMBC correlations for cembrane 3.

| Position | δH (J in Hz) | δC, Multiple | 1H–1H COSY | HMBC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.90 m | 37.4, CH | H2-2, H2-14 | C-2, -14, -15, -16, -17 |

| 2 | 2.19 m; 1.20 ddd (12.5, 12.5, 7.0) | 29.7, CH2 | H-1, H2-3 | C-1, -2, -3, -4, -14, -15 |

| 3 | 2.45 dd (15.5, 7.0); 1.91 m | 33.7, CH2 | H2-2 | C-1, -2, -4, -5, -18 |

| 4 | 90.0, C | |||

| 5 | 209.3, C | |||

| 6 | 3.36 dd (17.0, 9.5); 2.56 br d (17.0) | 33.6, CH2 | H2-7 | C-5, -7, -8 |

| 7 | 2.57 br d (16.0); 2.15 m | 31.0, CH2 | H2-6 | C-5, -6, -8, -9, -19 |

| 8 | 134.7, C | |||

| 9 | 4.99 dd (6.5, 6.5) | 124.9, CH | H2-10, H3-19 | C-7, -9, -10, -19 |

| 10 | 2.14 m | 23.5, CH2 | H-9, H2-11 | C-8, -9, -11, -12 |

| 11 | 1.66 m | 38.2, CH2 | H2-10 | C-9, -10, -12, -13, -20 |

| 12 | 76.2, C | |||

| 13 | 3.26 dd (6.0, 1.5) | 75.5, CH | H2-14 | C-1, -11, -14, -20 |

| 14 | 2.03 dd (14.5, 1.5) | 35.3, CH2 | H-1, H-13 | C-1, -2, -12, -13, -15 |

| 1.40 ddd (14.5, 11.0, 6.0) | ||||

| 15 | 143.3, C | |||

| 16 | 168.0, C | |||

| 17 | 6.35 s; 5.58 s | 126.0, CH2 | C-1, -15, -16 | |

| 18 | 1.49 s | 29.6, CH3 | C-3, -4, -5, -16 | |

| 19 | 1.69 s | 17.4, CH3 | H-9 | C-7, -8, -9 |

| 20 | 1.27 s | 24.6, CH3 | C-11, -12, -13 |

Figure 6.

1H–1H COSY and selected HMBC correlations (protons→quaternary carbons) for cembrane 3.

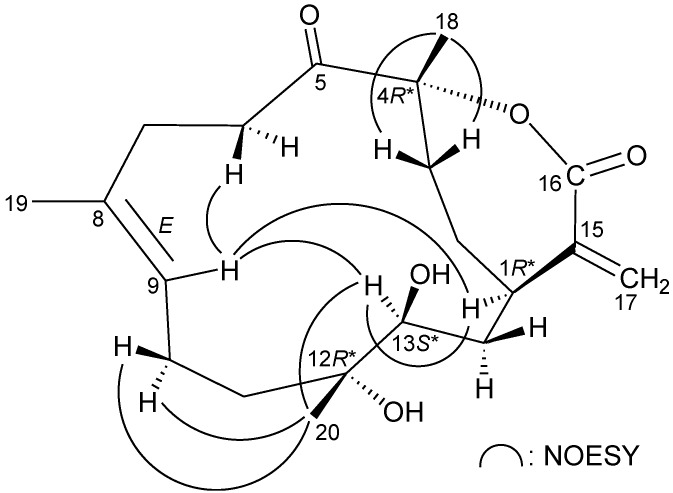

The relative stereochemistry of 3 was elucidated by the analysis of NOE correlations, as shown in Figure 7. H-9 exhibited a correlation with one of the C-6 methylene protons (δH 3.36), but not with H3-19, which revealed the E geometry of the C-8/9 double bond. It was found that H-13 showed correlations with H-1 and H-9. From molecular modeling analysis, H-13 was found to be close to H-1 and H-9, when H-1 and H-13 were α-oriented. Correlations observed between H3-20/H-13 and H3-20/H2-10 reflected the β-orientation of Me-20. Furthermore, H3-18 exhibited correlations with C-3 methylene protons and the lack of correlation between H3-18 and H-1, indicating that Me-18 was positioned on the β-face in 3. Thus, the structure of 3 was established, and the chiral carbons of 3 were assigned as 1R*, 4R*, 12R* and 13S*.

Figure 7.

Key NOESY correlations of 3.

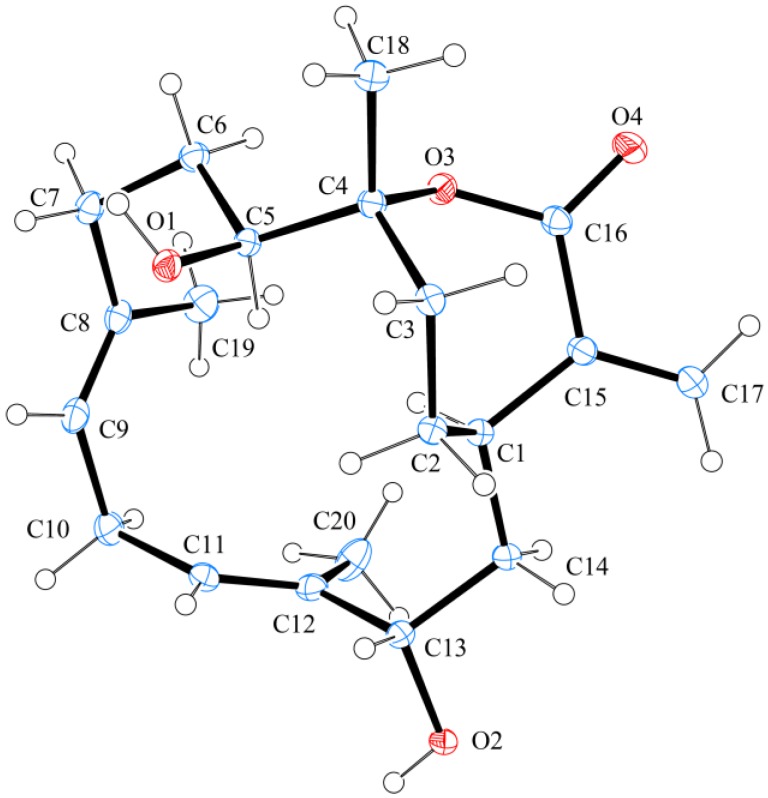

The known cembrane, (−)-sandensolide (4), was first isolated from a Chinese soft coral, Dendronephthya sp. [23], and its structure was elucidated by spectroscopic methods and by comparison of spectral (1D and 2D NMR) and physical (rotation value) data with those of its enantiomer, sandensolide [10,22]. In this study, the structure of 4, including its absolute stereochemistry, was further established by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis for the first time. The X-ray structure of 4 (Figure 8) demonstrates the E geometry of the C-8/9 and C-11/12 double bonds, and the absolute configurations for all chiral carbons were assigned as 1R, 4R, 5S and 13S. As flexibilins A–C (1–3) were isolated, along with (−)-sandensolide (4), from the same organism, it is reasonable on biogenetic grounds to assume that cembranes 1–3 have the same absolute configurations as 4.

Figure 8.

Molecular plot of 4 with confirmed absolute configuration.

The in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of cembranes 1–4 were examined, and cembrane 2 displayed a moderate inhibitory effect on the release of elastase by human neutrophils (Table 4) [24].

Table 4.

Inhibitory effects of cembranes 1–4 on the generation of superoxide anions and the release of elastase by human neutrophils in response to fMLP/CB.

| Compound | Superoxide anions | Elastase release | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (μg/mL) | Inh% a | IC50 (μg/mL) | Inh% a | |

| 1 | >10 | 12.31 ± 3.04 * | >10 | 22.67 ± 5.32 * |

| 2 | >10 | 22.03 ± 3.88 ** | >10 | 45.76 ± 2.92 *** |

| 3 | >10 | 18.80 ± 3.81 ** | >10 | 10.56 ± 2.75 * |

| 4 | >10 | −2.08 ± 1.01 | >10 | 8.14 ± 4.03 |

| LY294002 b | 0.41 ± 0.27 | 0.79 ± 0.18 | ||

a Percentage of inhibition (Inh%) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL. b LY294002, a phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase inhibitor, was used as a positive control for inhibition of superoxide anion generation and elastase release. The results are presented as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 3 or 4). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, compared with the control value.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured on a Jasco P-1010 digital polarimeter. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Varian Diglab FTS 1000 FT-IR spectrometer; peaks are reported in cm−1. The NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Inova 500 or on a Varian Mercury Plus 400 NMR spectrometer using the residual CHCl3 signal (δH 7.26 ppm) as the internal standard for 1H NMR and CDCl3 (δC 77.1 ppm) for 13C NMR. Coupling constants (J) are given in Hz. ESIMS and HRESIMS were recorded on a Bruker APEX II mass spectrometer. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel (230–400 mesh, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). TLC was carried out on precoated Kieselgel 60 F254 (0.25 mm, Merck); spots were visualized by spraying with 10% H2SO4 solution, followed by heating. HPLC was performed using a system comprised of a Hitachi L-7110 pump and a Rheodyne injection port. A normal phase semi-preparative column (Supelco Ascentis® Si cat#:581515-U, 250 × 21.2 mm, 5 μm) was used for HPLC.

3.2. Animal Material

Specimens of the octocoral S. flexibilis were collected by hand using scuba equipment off the coast of southern Taiwan in July, 2011, and stored in a freezer until extraction. A voucher specimen (NMMBA-TWSC-11005) was deposited in the National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium, Taiwan.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

Sliced bodies of the soft coral S. flexibilis (wet weight 3.0 kg, dry weight 950 g) were extracted with ethyl acetate (EtOAc). The EtOAc layer was separated by silica gel and eluted using n-hexane/EtOAc in a stepwise fashion from pure n-hexane–100:1–pure EtOAc to yield 11 fractions, A–K. Fraction J was chromatographed on silica gel and eluted using n-hexane/EtOAc (stepwise, 2:1–1:1) to afford subfractions 1–10. Fractions J3, J5 and J9 were separated by normal-phase HPLC (NP-HPLC) using a mixture of n-hexane and acetone as the mobile phase to afford 4 (3:1, 74.3 mg), 3 (2:1, 5.6 mg) and 2 (3:1, 16.6 mg), respectively. Fraction K was further purified by NP-HPLC using a mixture of n-hexane and acetone as the mobile phase to afford 1 (2:1, 22.4 mg).

Flexibilin A (1): yellowish oil;  −9 (c 0.47, CHCl3); IR (neat) νmax 3750–2400 (br.), 3419, 1711 cm−1; 1H (CDCl3, 500 MHz) and 13C (CDCl3, 125 MHz) NMR data—see Table 1; ESIMS: m/z 375 (M + Na)+; HRESIMS: m/z 375.2144 (calcd. for C20H32O5Na, 375.2147).

−9 (c 0.47, CHCl3); IR (neat) νmax 3750–2400 (br.), 3419, 1711 cm−1; 1H (CDCl3, 500 MHz) and 13C (CDCl3, 125 MHz) NMR data—see Table 1; ESIMS: m/z 375 (M + Na)+; HRESIMS: m/z 375.2144 (calcd. for C20H32O5Na, 375.2147).

Flexibilin B (2): colorless oil;  +29 (c 0.83, CHCl3); IR (neat) νmax 3700–2400 (br.), 3447, 1713 cm−1; 1H (CDCl3, 500 MHz) and 13C (CDCl3, 125 MHz) NMR data—see Table 2; ESIMS: m/z 373 (M + Na)+; HRESIMS: m/z 373.1989 (calcd. for C20H30O5Na, 373.1991).

+29 (c 0.83, CHCl3); IR (neat) νmax 3700–2400 (br.), 3447, 1713 cm−1; 1H (CDCl3, 500 MHz) and 13C (CDCl3, 125 MHz) NMR data—see Table 2; ESIMS: m/z 373 (M + Na)+; HRESIMS: m/z 373.1989 (calcd. for C20H30O5Na, 373.1991).

Flexibilin C (3): white powder; mp 95–97 °C;  +4 (c 0.28, CHCl3); IR (neat) νmax 3431, 1711 cm−1; 1H (CDCl3, 500 MHz) and 13C (CDCl3, 125 MHz) NMR data—see Table 3; ESIMS: m/z 373 (M + Na)+; HRESIMS: m/z 373.1989 (calcd. for C20H30O5Na, 373.1991).

+4 (c 0.28, CHCl3); IR (neat) νmax 3431, 1711 cm−1; 1H (CDCl3, 500 MHz) and 13C (CDCl3, 125 MHz) NMR data—see Table 3; ESIMS: m/z 373 (M + Na)+; HRESIMS: m/z 373.1989 (calcd. for C20H30O5Na, 373.1991).

(−)-Sandensolide (4): white powder; mp 178–180 °C;  −43 (c 0.67, CHCl3) (reference [23],

−43 (c 0.67, CHCl3) (reference [23],  −45.0 (c 0.5, CHCl3)); IR (neat) νmax 3431, 1691 cm−1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δH 6.24 (1H, s, H-17), 5.49 (1H, s, H-17′), 5.39 (1H, m, H-11), 5.36 (1H, m, H-9), 4.18 (1H, dd, J = 11.2, 4.4 Hz, H-13), 3.77 (1H, d, J = 10.4 Hz, H-5), 3.13 (1H, ddd, J = 13.2, 11.6, 10.4 Hz, H-10), 2.40 (1H, m, H-10′), 2.21 (1H, m, H-7), 2.13 (1H, m, H-3), 2.05 (1H, m, H-7′), 2.04 (1H, m, H-2), 2.01 (1H, m, H-1), 1.99 (1H, m, H-6), 1.80 (1H, m, H-14), 1.72 (1H, m, H-14′), 1.70 (1H, m, H-3′), 1.62 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.52 (3H, s, H3-19), 1.35 (1H, dddd, J = 14.0, 10.4, 3.6, 3.6 Hz, H-6′), 1.26 (3H, s, H3-20), 1.14 (1H, m, H-2′); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δC 169.6 (C-16), 144.6 (C-15), 134.2 (C-8), 132.7 (C-12), 127.9 (CH-11), 124.7 (CH-9), 124.4 (CH2-17), 86.6 (C-4), 76.6 (CH-13), 67.4 (CH-5), 38.0 (CH2-14), 34.8 (CH2-7), 33.7 (CH-1), 32.0 (CH2-3), 29.2 (CH2-2), 26.8 (CH2-10), 26.6 (CH2-6), 22.8 (CH3-18), 14.9 (CH3-19), 9.3 (CH3-20); ESIMS: m/z 357 (M + Na)+; HRESIMS: m/z 357.2040 (calcd. for C20H30O4Na, 357.2042).

−45.0 (c 0.5, CHCl3)); IR (neat) νmax 3431, 1691 cm−1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δH 6.24 (1H, s, H-17), 5.49 (1H, s, H-17′), 5.39 (1H, m, H-11), 5.36 (1H, m, H-9), 4.18 (1H, dd, J = 11.2, 4.4 Hz, H-13), 3.77 (1H, d, J = 10.4 Hz, H-5), 3.13 (1H, ddd, J = 13.2, 11.6, 10.4 Hz, H-10), 2.40 (1H, m, H-10′), 2.21 (1H, m, H-7), 2.13 (1H, m, H-3), 2.05 (1H, m, H-7′), 2.04 (1H, m, H-2), 2.01 (1H, m, H-1), 1.99 (1H, m, H-6), 1.80 (1H, m, H-14), 1.72 (1H, m, H-14′), 1.70 (1H, m, H-3′), 1.62 (3H, s, H3-18), 1.52 (3H, s, H3-19), 1.35 (1H, dddd, J = 14.0, 10.4, 3.6, 3.6 Hz, H-6′), 1.26 (3H, s, H3-20), 1.14 (1H, m, H-2′); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δC 169.6 (C-16), 144.6 (C-15), 134.2 (C-8), 132.7 (C-12), 127.9 (CH-11), 124.7 (CH-9), 124.4 (CH2-17), 86.6 (C-4), 76.6 (CH-13), 67.4 (CH-5), 38.0 (CH2-14), 34.8 (CH2-7), 33.7 (CH-1), 32.0 (CH2-3), 29.2 (CH2-2), 26.8 (CH2-10), 26.6 (CH2-6), 22.8 (CH3-18), 14.9 (CH3-19), 9.3 (CH3-20); ESIMS: m/z 357 (M + Na)+; HRESIMS: m/z 357.2040 (calcd. for C20H30O4Na, 357.2042).

3.4. Single-Crystal X-ray Crystallography of (−)-Sandensolide (4) [25]

Suitable colorless prisms of 4 were obtained from a solution of ethyl acetate. Crystal data and experimental details: C20H30O4, Mr = 334.44, crystal size 0.25 × 0.20 × 0.20 mm, crystal system monoclinic, space group P21 (#4), with a = 9.0281(3) Å, b = 22.2200(8) Å, c = 9.3289(3) Å, β = 100.547(1)°, V = 1839.80(11) Å,3, Z = 4, Dcalcd = 1.207 g/cm3 and λ (Cu, kα) = 1.54178 Å. Intensity data were measured on a Bruker APEX-II CCD diffractometer equipped with a micro-focus Cu radiation source and Montel mirror up to θmax of 26° at 100 K. All 5454 reflections were collected. The structure was solved by direct methods and refined by a full-matrix least-squares procedure. The refined structural model converged to a final R1 = 0.0294, wR2 = 0.0759 for 5398 observed reflection [I > 2σ(I)] and 455 variable parameters. The absolute configuration was determined by Flack’s method, with the Flack’s parameter determined as 0.06(10) [26].

3.5. Generation of Superoxide Anions and Release of Elastase by Human Neutrophils

Human neutrophils were obtained by means of dextran sedimentation and Ficoll centrifugation. Measurements of superoxide anion generation and elastase release were carried out according to previously described procedures [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Briefly, superoxide anion production was assayed by monitoring the superoxide dismutase-inhibitable reduction of ferricytochrome c. Elastase release experiments were performed using MeO-Suc-Ala-Ala-Pro-Valp-nitroanilide as the elastase substrate.

4. Conclusions

Cembrane-type diterpenoids are the major component of the organic extract of the soft coral, Sinularia flexibilis, collected from the waters of Taiwan, and compounds of this type have been shown to have the potential for use in medical applications. Our studies of S. flexibilis have led to the isolation of three new cembranes, flexibilins A–C (1–3), along with a known metabolite, (−)-sandensolide (4), and flexibilin B (2) displayed a moderate inhibitory effect on the release of elastase by human neutrophils. In addition to marine organisms, cembrane-type diterpenoids are also found in higher plants and bryophytes [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43]. However, the carboxylic acid moieties exhibited in cembranes 1 and 2 are rarely found [35,44]. The soft coral, S. flexibilis, has begun to be transplanted to culturing tanks with a flow-through seawater system located in the National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium, Taiwan, for exhibition and the extraction of additional natural products in order to establish a stable supply of bioactive material.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium; the National Dong Hwa University; the Division of Marine Biotechnology, Asia-Pacific Ocean Research Center, National Sun Yat-sen University (Grant No. 00C-0302-05); the Department of Health Clinical Trial and Research Center of Excellence (Grant No. DOH101-TD-C-111-004); and the National Science Council (Grant No. NSC 102-2325-B-291-001, 101-2325-B-291-001, 100-2325-B-291-001 and 101-2320-B-291-001-MY3), Taiwan; awarded to Y.-H.K. and P.-J.S.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Samples Availability: Not available.

References and Notes

- 1.Rocha J., Peixe L., Gomes N.C.M., Calado R. Cnidarians as a new marine bioactive compounds—An overview of the last decade and future steps for bioprospecting. Mar. Drugs. 2011;9:1860–1886. doi: 10.3390/md9101860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W.-T., Li Y., Guo Y.-W. Terpenoids of Sinularia soft corals: Chemistry and bioactivity. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2012;2:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tursch B., Braekman J.C., Daloze D., Herin M., Karlsson R., Losman D. Chemcial studies of marine invertebrates—XI. Tetrahedron. 1975;31:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(75)85006-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinheimer A.J., Matson J.A., Hossain M.B., van der Helm D. Marine anticancer agents: Sinularin and dihydrosinularin, new cembranolides from the soft coral, Sinularia flexibilis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977;18:2923–2926. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)83115-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazlauskas R., Murphy P.T., Wells R.J., Schönholzer P., Coll J.C. Cembranoid constituents from an Australian collection of the soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Aust. J. Chem. 1978;31:1817–1824. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mori K., Suzuki S., Iguchi K., Yamada Y. 8,11-Epoxy bridged cembranolide diterpene from the soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Chem. Lett. 1983;12:1515–1516. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerrero P.P., Read R.W., Batley M., Janairo G.C. The structure of a novel cembranoid diterpene from a Philippine collection of the soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. J. Nat. Prod. 1995;58:1185–1191. doi: 10.1021/np50122a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anjaneyulu A.S.R., Sagar K.S. Flexibilolide and dihydroflexibilolide, the first trihydroxy-cembranolide lactones from the soft coral Sinularia flexibilis of the Indian Ocean. Nat. Prod. Lett. 1996;9:127–135. doi: 10.1080/10575639608044936. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michalek K., Bowden B.F. A natural algacide from soft coral Sinularia flexibilis (Coelenterata, Octocorallia, Alcyonacea) J. Chem. Ecol. 1997;23:259–273. doi: 10.1023/B:JOEC.0000006358.47272.56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anjaneyulu A.S.R., Sagar K.S., Rao G.V. New cembranoid lactones from the Indian Ocean soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. J. Nat. Prod. 1997;60:9–12. doi: 10.1021/np960103o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duh C.-Y., Wang S.-K., Tseng H.-K., Sheu J.-H., Chiang M.Y. Novel cytotoxic cembranoids from the soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:844–847. doi: 10.1021/np980021v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duh C.-Y., Wang S.-K., Tseng H.-K., Sheu J.-H. A novel cytotoxic biscembranoid from the Formosan soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:7121–7122. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(98)01512-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsieh P.-W., Chang F.-R., McPhail A.T., Lee K.-H., Wu Y.-C. New cembranolide analogues from the Formosan soft coral Sinularia flexibilis and their cytotoxicity. Nat. Prod. Res. 2003;17:409–418. doi: 10.1080/14786910310001617677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen T., Ding Y., Deng Z., van Ofwegen L., Proksch P., Lin W. Sinulaflexiolides A–K, cembrane-type diterpenoids from the Chinese soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:1133–1140. doi: 10.1021/np070640g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo K.-L., Khalil A.T., Kuo Y.-H., Shen Y.-C. Sinuladiterpenes A–F, new cembrane diterpenes from Sinularia flexibilis. Chem. Biodivers. 2009;6:2227–2235. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Su J.-H., Lin Y.-F., Lu Y., Yeh H.-C., Wang W.-H., Fan T.-Y., Sheu J.-H. Oxygenated cembranoids from the cultured and wild-type soft corals Sinularia flexibilis. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2009;57:1189–1192. doi: 10.1248/cpb.57.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Y.-S., Chen C.-H., Liaw C.-C., Chen Y.-C., Kuo Y.-H., Shen Y.-C. Cembrane diterpenoids from the Taiwanese soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:9157–9164. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.09.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lo K.-L., Khalil A.T., Chen M.-H., Shen Y.-C. New cembrane diterpenes from Taiwanese soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2010;93:1329–1335. doi: 10.1002/hlca.200900386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen B.-W., Chao C.-H., Su J.-H., Huang C.-Y., Dai C.-F., Wen Z.-H., Sheu J.-H. A novel symmetric sulfur-containing biscembranoid from the Formosan soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:5764–5766. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih H.-J., Tseng Y.-J., Huang C.-Y., Wen Z.-H., Dai C.-F., Sheu J.-H. Cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory diterpenoids from the Dongsha Atoll soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:244–249. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su C.-C., Wong B.-S., Chin C., Wu Y.-J., Su J.-H. Oxygenated cembranoids from the soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:4317–4325. doi: 10.3390/ijms14024317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anjaneyulu A.S.R., Rao G.V., Sagar K.S., Kumar K.R., Mohan K.C. Sandensolide: A new dihydroxycembranolide from the soft coral, Sinularia sandensis Verseveldt of the Indian Ocean. Nat. Prod. Lett. 1995;7:183–190. doi: 10.1080/10575639508043209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma A., Deng Z., van Ofwegen L., Bayer M., Proksch P., Lin W. Dendronpholides A–R, cembranoid diterpenes from the Chinese soft coral Dendronephthya sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:1152–1160. doi: 10.1021/np800003w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.In the in vitro anti-inflammatory bioassay, the inhibitory effects on the generation of superoxide anion and the release of elastase by activated neutrophils were used as indicators. For significant activity of pure compounds, an inhibition rate ≥ 50% is required (inhibition rate ≤ 10%, not active; 20% ≥ inhibition rate ≥ 10%, weakly anti-inflammatory; 50% ≥ inhibition rate ≥ 20%, modestly anti-inflammatory).

- 25.Crystallographic data for the structure of (−)-sandensolide (4) have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center as supplementary publication number CCDC 931762. Copies of the data can be obtained, free of charge, on application to CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK [Fax: +44-(0)-1223-336033 or E-Mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk].

- 26.Flack H.D. On enantiomorph-polarity estimation. Acta Crystallogr. 1983;A39:876–881. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu H.-P., Hsieh P.-W., Chang Y.-J., Chung P.-J., Kuo L.-M., Hwang T.-L. 2-(2-Fluorobenzamido)benzoate ethyl ester (EFB-1) inhibits superoxide production by human neutrophils and attenuates hemorrhagic shock-induced organ dysfunction in rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011;50:1737–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hwang T.-L., Wang C.-C., Kuo Y.-H., Huang H.-C., Wu Y.-C., Kuo L.-M., Wu Y.-H. The hederagenin saponin SMG-1 is a natural FMLP receptor inhibitor that suppresses human neutrophil activation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;80:1190–1200. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang T.-L., Su Y.-C., Chang H.-L., Leu Y.-L., Chung P.-J., Kuo L.-M., Chang Y.-J. Suppression of superoxide anion and elastase release by C18 unsaturated fatty acids in human neutrophils. J. Lipid Res. 2009;50:1395–1408. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800574-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hwang T.-L., Li G.-L., Lan Y.-H., Chia Y.-C., Hsieh P.-W., Wu Y.-H., Wu Y.-C. Potent inhibition of superoxide anion production in activated human neutrophils by isopedicin, a bioactive component of the Chinese medicinal herb Fissistigma oldhamii. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009;46:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hwang T.-L., Leu Y.-L., Kao S.-H., Tang M.-C., Chang H.-L. Viscolin, a new chalcone from Viscum coloratum, inhibits human neutrophil superoxide anion and elastase release via a cAMP-dependent pathway. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006;41:1433–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang T.-L., Yeh S.-H., Leu Y.-L., Chern C.-Y., Hsu H.-C. Inhibition of superoxide anion and elastase release in human neutrophils by 3′-isopropoxychalcone via a cAMP-dependent pathway. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006;148:78–87. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang T.-L., Hung H.-W., Kao S.-H., Teng C.-M., Wu C.-C., Cheng S.J.-S. Soluble guanylyl cyclase activator YC-1 inhibits human neutrophil functions through a cGMP-independent but cAMP-dependent pathway. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;64:1419–1427. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manns D., Hartmann R. Echinodol: A new cembrane derivative from Echinodorus grandiflorus. Planta Med. 1993;59:465–466. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka C.M.A., Sarragiotto M.H., Zukerman-Schpector J., Marsaioli A. A cembrane from Echinodorus grandiflorus. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:1547–1549. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shigemori H., Shimamoto S., Sekiguchi M., Ohsaki A., Kobayashi J. Echinodolides A and B, new cembrane diterpenoids with an eight-membered lactone ring from the leaves of Echinodorus macrophyllus. J. Nat. Prod. 2002;65:82–84. doi: 10.1021/np0104119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shy H.-S., Wu C.-L., Paul C., König W.A., Ean U.-J. Chemical constituents of two liverworts Metacalypogeia alternifolia and Chandonanthus hirtellus. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2002;49:593–598. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garcez F.R., Garcez W.S., da Silva A.F.G., de Cássia Bazzo R., Resende U.M. Terpenoid constituents from leaves of Guarea kunthiana. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2004;15:767–772. doi: 10.1590/S0103-50532004000500025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y.-L., Lan Y.-H., Hsieh P.-W., Wu C.-C., Chen S.-L., Yen C.-T., Chang F.-R., Hung W.-C., Wu Y.-C. Bioactive cembrane diterpenoids of Anisomeles indica. J. Nat. Prod. 2008;71:1207–1212. doi: 10.1021/np800147z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li L.-M., Li G.-Y., Pu J.-X., Xiao W.-L., Ding L.-S., Sun H.-D. ent-Kaurane and cembrane diterpenoids from Isodon sculponeatus and their cytotoxicity. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:1851–1856. doi: 10.1021/np900406c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y., Harrison L.J., Tan B.C. Terpenoids from the liverwort Chandonanthus hirtellus. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:4035–4043. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komala I., Ito T., Nagashima F., Yagi Y., Kawahata M., Yamaguchi K., Asakawa Y. Zierane sesquiterpene lactone, cembrane and fusicoccane diterpenoids, from the Tahitian liverwort Chandonanthus hirtellu. Phytochemistry. 2010;71:1387–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asakawa Y., Ludwiczuk A., Nagashima F. Chemical Constituents of Bryophytes: Bio- and Chemical Diversity, Biological Activity, and Chemosystematics; Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products; 2013; Vienna, Austria: Springer; pp. 1–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonnard I., Jhaumeer-Laulloo S.B., Bontemps N., Banaigs B., Aknin M. New lobane and cembrane diterpenes from two Comorian soft corals. Mar. Drugs. 2010;8:359–372. doi: 10.3390/md8020359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]