Abstract

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue outside the lining of the uterine cavity. It occurs most commonly in pelvic sites such as ovaries, cul-de-sac, and fallopian tubes but also can be found associated with the lungs, bowel, ureter, brain, and abdominal wall. Abdominal wall endometriosis, also known as scar endometriosis, is extremely rare and mainly occurs at surgical scar sites. Although many cases of scar endometriosis have been reported after a cesarean section, some cases of scar endometriosis have been reported after an episiotomy, hysterectomy, appendectomy, and laparoscopic trocar port tracts. To our knowledge, 14 case reports related to trocar site endometriosis have been published in the English language literature to date. Herein, we present the case of a 20-year-old woman (who had been previously operated on for left ovarian endometrioma 1.5 years ago by laparoscopy) with the complaint of a painful mass at the periumbilical trocar site with cyclic pattern. Consequently, although rare, if a painful mass in the surgical scar, such as the trocar site, is found in women of reproductive age with a history of pelvic or obstetric surgery, the physician should consider endometriosis.

Keywords: Endometriosis, trocar site implantation, laparoscopy

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of functioning endometrial glands and stroma outside the usual location in the lining of the uterine cavity.1–3 Endometriosis is found most commonly in the gynecologic organs and pelvic peritoneum but may frequently involve the gastrointestinal system, greater omentum, and surgical scars, while it is rarely found in distant sites such as the kidney, lung, skin, and nasal cavity.4 Endometriomas have been found in association with surgical scars from a variety of procedures. With the increased use of laparoscopy, a few case reports have described abdominal wall endometriomas at port sites.5–18 This study presents the case of a patient with endometriotic trocar site metastasis who had previously undergone laparoscopic resection of a left ovarian endometriotic cyst.

Case Report

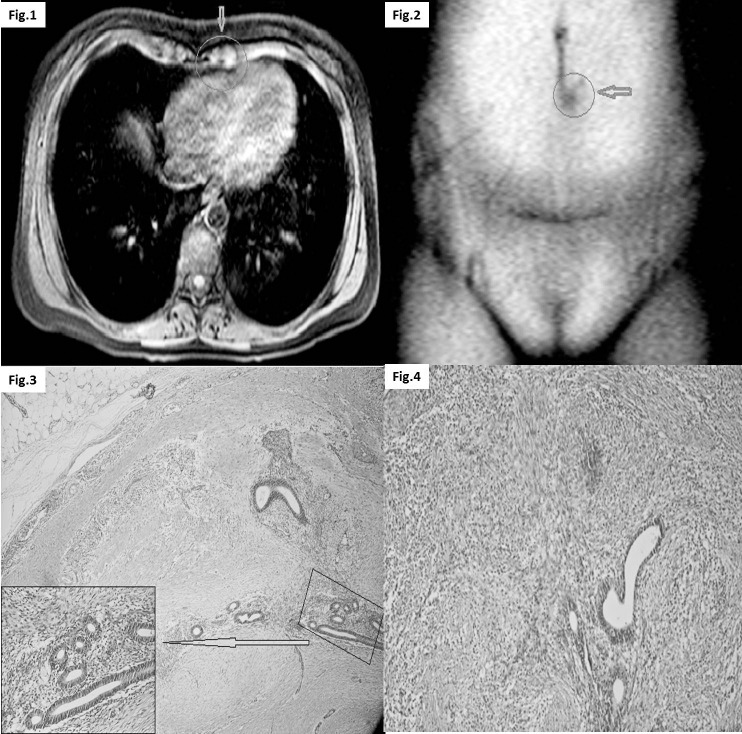

A 20-year-old female patient, who was married and had a child, was admitted to our outpatient clinic complaining of pain and a palpable swelling in the abdominal wall. Her medical history included an appendectomy 5 years earlier, a cesarean section 2 years earlier, and a laparoscopic left-sided ovarian cyst excision 1.5 years earlier. Before the previous laparoscopic operation, a 61 × 56-mm heterogeneous cyst localized in the left ovary, along with free fluid in the pouch of Douglas, had been detected on radiologic imaging to investigate severe abdominal pain and dyspareunia, and an explorative laparoscopy using 2 trocars had been performed with the provisional diagnosis of corpus hemorrhagicum cyst rupture. At laparoscopy, a chocolate-type cyst was detected in the left ovary, and free fluid with a hemorrhagic component was present in the pelvis. Histopathologic evaluation of the cystectomy material had confirmed the diagnosis of endometriosis, and the patient was placed on medical therapy. On this admission, she stated that the pain in the abdominal wall commenced a few months after the laparoscopic surgery, was cyclic in nature, and had worsened progressively over the previous 4 months. Inspection showed 2 healed scars compatible with trocar port sites: one inferior to the umbilicus (periumbilical trocar; 10 mm) and the other over the rectus muscle on the left side (left side trocar; 5 mm). On palpation, a hard, painful mass fixed to the surrounding tissues was detected at the 10-mm trocar port site. In routine biochemical tests, β-hCG and CA-125 were within normal ranges. Superficial tissue sonography revealed a 26 × 16-mm hypoechoic lesion lacking vascularity. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an iso-hyperintense mass localized approximately 2 to 3 cm below the umbilicus and just to the left of the midline (Figs. 1 and 2). At surgical exploration under spinal anesthesia, a 4 × 3-cm dense mass, which was fixed to the surrounding tissues and extended into the posterior rectus fascia, was observed. The mass was excised together with the fascia, and the abdomen was closed primarily. Pathologic examination revealed foci of endometriosis comprising endometrial glands and stroma within connective tissue, along with hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Figs. 3 and 4). The patient was referred to a gynecologist, who placed her on buserelin nasal spray.

Figure 1.

Axial MRI shows a mass just the left of the midline is compatible with endometriosis (arrow).

Fig. 2 Coronal MRI shows a mass approximately 2 to 3 cm below the umbilicus and just to the left of the midline is compatible with the trocar port site endometriosis (arrow).

Fig. 3 Foci of endometriosis comprising endometrial glands and stroma within connective tissue in the neighborhood of adipose tissue. H&E (×40).

Fig. 4 Endometrial glands and hemosiderin-laden macrophages within the stroma. H&E (×100).

Discussion

Endometriosis, first described by Rokitansky in 1861, is a common benign gynecologic disorder defined as the ectopic implantation of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity. Endometriosis is classified as internal or external according to the involvement of the uterine muscle layer. In internal endometriosis, the endometrial tissue is found within the uterine muscles. External endometriosis is commonly found in the pelvic genital organs (ovaries, cul-de-sac, and fallopian tubes) and other parts of the body.5,19,20 Endometriosis can also be classified as pelvic or extrapelvic according to its location. Pelvic endometriosis includes lesions of the fallopian tubes, ovaries, and pelvic peritoneum. Extrapelvic endometriosis refers to endometriotic implants found in other areas of the body, including the gastrointestinal tract, pulmonary structures, urinary system, abdominal wall, skin, and even the central nervous system.

The precise etiopathogenesis of endometriosis remains controversial, and many theories have been proposed, including cellular immunity, coelomic metaplasia, implantation or retrograde menstruation, vascular and lymphatic metastasis, dissemination, and direct transplantation.5,20,21 Direct transplantation is probably the mechanism responsible for the development of a scar endometrioma following a caesarian delivery, hysterectomy, appendectomy, laparoscopic trocar tract, or episiotomy.21 A trocar port site endometrioma might develop from the peritoneal seeding of cells because of pneumoperitoneum or from direct contact of the excised lesion with the port tract.5,8

The abdominal wall is an uncommon site of extrapelvic (external) endometriosis, where it usually develops in old surgical scars. Endometriosis has been reported in many types of surgical scars, including the scars resulting from endoscopy, cesarean section, tubal ligation, hysterectomy, inguinal hernia repair, laparotomy, and the needle tract of third trimester diagnostic amniocentesis. Scar endometriosis has also been reported in a laparoscopic trocar port site.

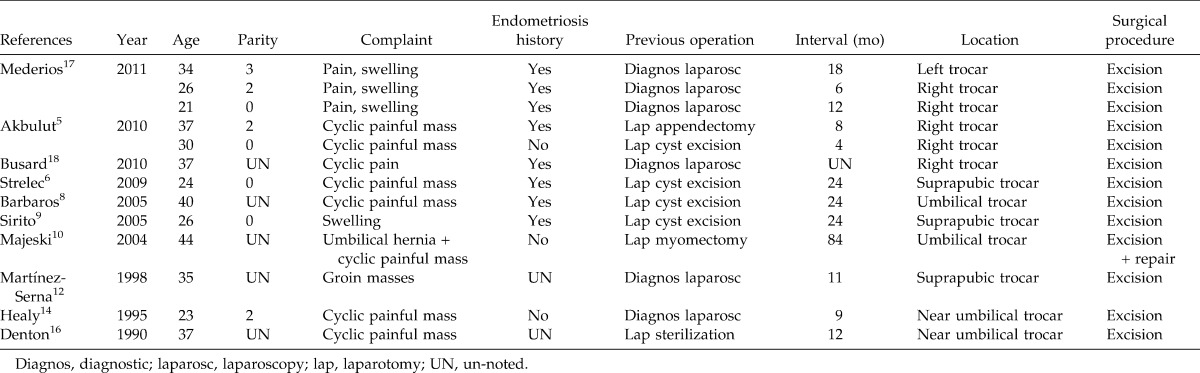

With the introduction of laparoscopy into both general and gynecologic surgery over the past 20 years, many complications associated with trocar port sites have been reported. Whereas the most frequent complication is an incisional hernia, especially with large-diameter trocars, tumor cell seeding along the trocar tract and trocar site endometriosis are two rare complications.9 The widespread use of laparoscopic approaches by gynecologists for ovarian cyst excision, tubal ligation, and exploration in attempts to elucidate the origins of pelvic pain can result in the development of trocar site endometriosis due to the simultaneous presence of asymptomatic endometriosis in a proportion of these patients. Denton et al. reported the first case of trocar site endometriosis in 1990.16 In searches of the PubMed, Google Scholar, and Medline databases using the search terms “endometriosis,” “scar endometriosis,” “abdominal wall endometriosis,” and “trocar,” alone and in various combinations, we found 14 English-language articles on trocar site endometriosis.5–18 Table 1 summarizes the data from the 10 articles (13 patients) for which we obtained the full text.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 13 patients with trocar site endometriosis

Patients with endometriosis in a surgical scar are often referred to general surgeons on suspicion of an incisional or inguinal hernia, rectus abdominis hematoma, mass, or suture granuloma. The diagnosis of scar endometriosis is usually highly suggestive from the patient's history and examination. This diagnosis is generally not difficult to reach in patients with the classic presentation of a palpable mass, cyclic pain, and a previous incision, especially in cases of cesarean delivery or a gynecologic procedure that opened the uterine cavity or treated pelvic endometriosis.5,21

Endometriosis arising from an abdominal wall scar, such as a trocar site, can be detected using computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography (USG), ultrasound (US)-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA), and MRI.5 On USG, the masses appear as solid, hypoechoic lesions in the abdominal wall that contain internal vascularity on power Doppler examination. The CT and MRI characteristics of abdominal wall endometriosis are nonspecific, with both showing a solid enhancing mass in the abdominal wall. The major role of CT and MRI may be to depict the extent of the disease preoperatively. Although useful, CT, USG, and MRI cannot provide a definitive preoperative diagnosis. US-guided FNA is a rapid, accurate diagnostic procedure in women with abdominal wall masses associated with endometriosis, enabling malignancy to be excluded and definitive treatment to be determined.20

The differential diagnosis of surgical scar endometriosis is broad and is often confused with other pathologic conditions, such as a suture granuloma, abscess, inguinal or incisional hernia, soft-tissue sarcoma, desmoid tumor, lipoma, metastatic tumor, and sebaceous cyst. Therefore, the pathologic diagnosis of endometriosis should be confirmed.5

The treatment of choice for scar endometriosis is wide local excision of the lesion with negative margins, even for recurrent disease. Medical therapy is also used in the treatment of scar endometriosis and includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, oral contraceptives, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues, aromatase inhibitors, and radiofrequency ablation therapy.5 In our opinion, the development of trocar site endometriosis can be prevented by precautions such as removing specimens from the abdominal cavity in endo bags and washing the incision sites, as well as careful closure of the abdominal cavity in patients with a history of endometriosis or in those in whom pelvic endometriosis was revealed during laparoscopy.

Postoperative follow-up with a gynecologist is recommended, as concomitant pelvic endometriosis may be encountered in patients with abdominal wall endometriosis in a surgical scar. CA-125, a marker found on derivatives of the coelomic epithelium, may be useful in some patients for predicting the presence and recurrence of endometriosis.

In conclusion, although rare, if a painful mass in a surgical scar such as a trocar site is found in women of reproductive age with a history of pelvic or obstetric surgery, the physician should consider endometriosis.

References

- 1.Akbulut S, Dursun P, Kocbiyik A, Harman A, Sevmis S. Appendiceal endometriosis presenting as perforated appendicitis: report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280(3):495–497. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0922-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laskou S, Papavramidis T.S, Cheva A, Michalopoulos N, Koulouris C, Kesisoglou I, et al. Acute appendicitis caused by endometriosis: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2011;5(1):144. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gustofson R.L, Kim N, Liu S, Stratton P. Endometriosis and the appendix: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(2):298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tazaki T, Oue N, Ichikawa T, Tsumura H, Hino H, Yamaoka H, et al. A case of endometriosis of the appendix. Hiroshima J Med Sci. 2010;59(2):39–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akbulut S, Sevinc M.M, Bakir S, Cakabay B, Sezgin A. Scar endometriosis in the abdominal wall: a predictable condition for experienced surgeons. Acta Chir Belg. 2010;110(3):303–307. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2010.11680621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strelec M, Dmitrovic R, Matkovic S. Trocar scar endometriosis. Gynaecol Perinatol. 2009;188(1):34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farace F, Gallo A, Rubino C, Manca A, Campus G.V. Endometriosis in a trocar tract: is it really a rare condition? A case report. Minerva Chir. 2005;60(1):67–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbaros U, Iyibozkurt A.C, Gulluoglu M, Barbaros M, Erbil Y, Tunali V, et al. Endometriotic umbilical port site metastasis after laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1761–1763. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sirito R, Puppo A, Centurioni M.G, Gustavino C. Incisional hernia on the 5-mm trocar port site and subsequent wall endometriosis on the same site: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3, pt 1):878–880. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majeski J, Craggie J. Scar endometriosis developing after an umbilical hernia repair with mesh. South Med J. 2004;97(5):532–534. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200405000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koninckx P.R, Donders G, Vandecruys H. Umbilical endometriosis after unprotected removal of uterine pieces through the umbilicus. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(2):227–232. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(00)80045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martínez-Serna T, Stalter K.D, Filipi C.J, Tomonaga T. An unusual case of endometrial trocar site implantation. Surg Endosc. 1998;12(7):992–994. doi: 10.1007/s004649900763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakefield S.E, Hellen E.A. Endometrioma of the trocar site after laparoscopy. Eur J Sur. 1996;162(6):523–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Healy J.T, Wilkinson N.W, Sawyer M. Abdominal wall endometrioma in a laparoscopic trocar tract: a case report. Am Surg. 1995;61(11):962–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thylan S. Re: abdominal wall endometrioma in a laparoscopic trocar tract: a case report. Am Surg. 1996;62(7):617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denton G.W, Schofield J.B, Gallagher P. Uncommon complications of laparoscopic sterilisation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72(3):210–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medeiros F.C, Cavalcante D.I, Medeiros M.A, Eleuterio J., Jr Fine-needle aspiration cytology of scar endometriosis: study of seven cases and literature review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2011;39(1):18–21. doi: 10.1002/dc.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busard M.P, Mijatovic V, van Kuijk C, Hompes P.G, van Waesberghe J.H. Appearance of abdominal wall endometriosis on MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2010;20(5):1267–1276. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1658-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uncu H, Taner D. Appendiceal endometriosis: two case reports. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278(3):273–275. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0570-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hensen J.H, Van Breda Vriesman A.C, Puylaert J.B. Abdominal wall endometriosis: clinical presentation and imaging features with emphasis on sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(3):616–620. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang Y, Tsai E.M, Long C.Y, Chen Y.H, Kay N. Abdominal wall endometriomas. J Reprod Med. 2009;54(3):155–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]