Abstract

Background & objectives:

The objectives of the study were to examine: right to access maternal health; right to access child health; and right to access improved water and sanitation in India.

Methods:

We used large-scale data sets like District Level Household Survey conducted in 2007-08 and National Family Health Surveys conducted during 1992-93, 1998-99, and 2005-06 to fulfil the objectives. The selection of the indicator variables was guided by the Human Rights’ Framework for Health and Convention of the Rights of the Child- Articles 7, 24 and 27. We used univariate and bivariate analysis along with ratio of access among non-poor to access among poor to fulfil the objectives.

Results:

Evidence clearly suggested gross violation of human rights starting from the birth of an individual. Even after 60 years of independence, significant proportions of women and children do not have access to basic services like improved drinking water and sanitation.

Interpretation & conclusions:

There were enormous socio-economic and residence related inequalities in maternal and child health indicators included in the study. These inequalities were mostly to the disadvantage of the poor. The fulfilment of the basic human rights of women and children is likely to pay dividends in many other domains related to overall population and health in India.

Keywords: Child health, Human Rights, improved water and sanitation, inequalities, maternal healht

Human rights are “basic rights and freedoms that all people are entitled to regardless of nationality, sex, national or ethnic origin, race, religion, language, or other status”1. Human rights are conceived as universal and egalitarian, with all people having equal rights by virtue of being human2. These rights may exist as natural rights or as legal rights. The UN in its charter clearly outlined to promote universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion3,4. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948, partly in response to the atrocities of World War II. However, the reproductive rights only began to develop as a ‘subset’ of human rights at the United Nation's International Conference on Human Rights held in Tehran in 19684. This conference for the first time deliberated that ‘parents’ have a basic human right to determine freely and responsibly the number and the spacing of their children5. The most important document to emerge was the ‘Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women’. The Convention adopted in 1979 aimed to achieve equality between men and women in their right and ability to control reproduction4. The Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing provided a broader context of reproductive rights and stated - ‘The human rights of women include their right to have control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health, free of coercion, discrimination and violence6.

Indian constitution has very clearly and specifically stated ‘protection and fulfillment of right to health for all - right to life, equality and non-discrimination’7. The right to health requires that health care should be available, accessible, affordable, and of optimal quality to all. The Constitution of India makes it mandatory for the State to ensure fulfillment of the right to health for all without any discrimination under Articles 14, 15 and 21 (rights to life, equality and nondiscrimination)7. This automatically leads to the understanding that the nation must Respect, Protect, Fulfill, and Guarantee Human Rights without discrimination based on caste, class, creed or sex.

The rights’ based approach attempts to ensure that the strategies to address the growing socio-economic inequalities are not only put in place but also focus on in-built mechanisms to achieve the goals without discrimination. Moreover, the rights’ based approach ensures that ‘State’ commits to financial allocations necessary for making health accessible and available to everyone. For example, if all women had access to the interventions for addressing complications of pregnancy and childbirth, especially emergency obstetric care, 74 per cent of all maternal deaths could be averted8. Family planning (meeting the unmet need for contraception) alone can contribute to 30-33 per cent reduction in maternal mortality8. Undoubtably, it is the women and the children who are more vulnerable and have relatively lower access to right to good health compared to men.

The study was undertaken with three main objectives: first, to examine right to access maternal health; second, to examine right to access child health; and third, to examine right to access improved water and sanitation in India using data from various large-scale household surveys conducted in the country in the last two decades.

Material & Methods

The data from various large-scale household surveys like District Level Household Survey (DLHS) conducted in 2007-2008 (to be referred as DLHS-3 subsequently) and National Family Health Surveys conducted during 1992-1993, 1998-1999, and 2005-2006 (to be referred as NFHSs subsequently) were used9,10,11,12. Since these surveys were conducted at different points of time, the first being conducted in 1992-1993 and the last being in 2007-2008, provided us a unique opportunity to examine the level and trends in selected indicators. These surveys covered more than 99% of India's population and thus any estimates generated using these datasets are representative at the national, State and district levels.

The right to access maternal health was examined with the help of three key components namely; ‘unmet need for contraceptives’, ‘access to services related to pregnancy and delivery’ and ‘preparedness of the programme to provide services and handle emergencies’. The selection of the three components was based on the Human Rights Framework for Health forwarded by Hunt13.

Convention on the Rights of the Child- Articles 7, 24 and 2714 were used to examine the right to access child health. The Article 7 of the Convention specifies that every child shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have the right from birth to a name, the right to acquire a nationality and as far as possible, the right to know and be cared for by his or her parents. The Article 24 of the Convention commits that the national governments are committed to diminish infant and child mortality, ensure the provision of necessary medical assistance and health care to all children with emphasis on the development of primary health care, combat disease and malnutrition, and ensure appropriate pre-natal and post-natal health care for mothers. The Article 27 of the Convention emphasizes on recognizing the rights of every child to a standard of living adequate for the child's physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development14. To address the three Articles, the discussion on ‘right to access child health’ was divided into three parts namely ‘Birth Registration’, ‘Preventive Care – newborn care, child malnutrition and child immunization’, and ‘Curative Care – knowledge of oral rehydration salt and use of oral rehydration salts (ORS), and knowledge of danger signs of acute respiratory infections (ARIs)’.

The main explanatory variable used in the analysis is a proxy measure of wealth - more commonly known as wealth index. Direct data on income or expenditure are not available in any of the selected household surveys and in circumstances where such data available in retrospective surveys are subject to reporting bias, a wealth index is computed based on the ownership of household assets and consumer durables15,16,17,18,19,20,21.

Univariate and bivariate analyses were used along with ratio of access among non-poor to access among poor to fulfill the objectives of the study. Univariate and bivariate analyses were applied to understand the access to maternal and child health and access to improved water and sanitation. The ratio of access among non-poor to access among poor was used to understand the socio-economic inequalities in access to the three sets of basic human rights. Further, trend analysis was performed to examine the changes in access in general and changes in socio-economic inequalities in access in particular over the last two decades.

Results

1. Right to access maternal health

Access to and use of family planning: Evidence from DLHS-3 suggested that during antenatal sessions less than 25-30 per cent of the women from poor and marginalized households were advised on contraception compared to more than 50 per cent from the rich households. In addition, rich-poor ratio in advice received during pregnancy suggests that compared to the poor women, rich women were twice more likely to have received advice on spacing and limiting methods of contraception. These suggested discrimination on the part of the health service providers.

A majority of the Indian women (more than 69 per cent) reporting any unmet need for family planning belong to the under-privileged sections of society. In other words, nearly 29 million Indian women whose reproductive rights are violated are economically poor or come from the families that are below poverty line (unpublished observation using NFHS and Census datasets). There were also huge variations across the different States as well as across geographic regions of the country. Evidence from DLHS-3 suggested that more than 30 per cent of the women in States of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar had unmet need for family planning; a level far above the national average. Converting these figures into numbers suggested that a large chunk of women who reported unmet need for family planning resided in the demographically poor-performing States of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh.

Evidence from various large-scale household surveys suggested an unmet need of about 21 per cent at the all India level, (circa 2007)11,12. If this is translated into number, nearly 42 million couples in India want to control their fertility but are unable to translate their desire into practice due to various reasons including those related to socio-economic and cultural beliefs that act as barriers in utilization of such services. All these factors act as barriers in meeting the ‘reproductive rights’ of large number of Indian women and men resulting into huge burden of unwanted pregnancies, unsafe and illegal abortions, and maternal morbidity and mortality.

Access to services related to pregnancy and delivery: The rich-poor ratio in advice received during pregnancy suggested that compared to poor women, rich women were twice as likely to have received advice on institutional delivery. With respect to the registration of pregnancy, women from rich households were again twice as likely as poor women to register their last pregnancy. The differences were not only limited to the advice given during pregnancy, but these became more pronounced for utilization of maternal care services. Recent WHO recommendations suggest that to ensure good maternal health, every pregnant woman, irrespective of her social or economic status, must receive at least four visits during her pregnancy and that the first visit should preferably be made in the first trimester22. The rich-poor gap in utilization of recommended care was marked in each of the three rounds of NFHS. The rich-poor ratio increased dramatically from 3.8 in 1992-1993 to 5.7 in 2005-2006 suggesting that the rich-poor gap has actually widened over time. Surprisingly, the utilization of recommended care by poor women remained unchanged over the last two decades (about 6%).

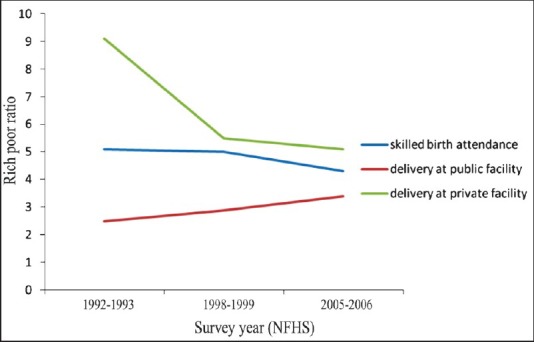

Data on institutional deliveries presented a forbidding picture. Variations in utilization of skilled birth attendance (SBA) by wealth quintiles were marked – 90 per cent of pregnant women from richest households delivering their children under supervision compared to only 20 per cent of women from poorest households. Public versus private disaggregation suggested that in 1992-1993, women from the rich households were only twice more likely to have received skilled attendance at a public facility as compared to the poor women (Fig. 1). This advantage of the rich women to deliver in a public facility increased by three-folds in 2005-2006. In complete contrast to this pattern, the advantage of rich women over poor women to deliver in a private facility declined from 9 times in 1992-1993 to only 5 times in 2005-2006. The findings suggest that the chances for the rich to deliver in a public facility are increasing while the poor are more likely to deliver in a private facility.

Fig. 1.

Rich-poor ratio in skilled birth attendance, India, various rounds of NFHS.

Socio-economic inequalities were not only found between States but were also pronounced within States; irrespective of their level of development. For example, in Bihar, the percentage of institutional delivery range from 12 per cent in Katihar and Sheohar districts to 59 per cent in Patna. In Karnataka, the percentage of institutional delivery ranged between 25 per cent in Koppal and 96 per cent in Dakshina Kannada. Such disparities were also observed in many of the other States of India.

The data showed that the use of ANC and SBA was disproportionately lower among poor women in India, irrespective of area and State of residence. Not only was the rich-poor gap significant, but the fact that the rich-poor inequalities were widening with declining averages is of much higher concern. A recent study by Lim et al25 suggested that poor and marginalized women were not always at higher odds of receiving incentives under ‘Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY)’ scheme of the Government of India in spite of the fact that JSY scheme was particularly articulated to help the poor and the marginalized groups. Variations in rich-poor gap by States were marked.

Preparedness of the programme to provide services and handle emergencies: The ideal scenario is that every birth, whether it takes place at home or in a facility, takes place under the supervision of a skilled birth attendant backed up by facilities that can provide emergency obstetric care and by an effectively functioning referral system that ensures timely access to appropriate services in case of any life-threatening complication. Data from the two rounds of facility survey under the DLHS indicate that the health system in India is inadequately prepared to handle medical emergencies. Data from DLHS-3 suggest that only 24 per cent of the Primary Health Centers (PHCs) in the country had a lady medical officer. Only 68 per cent of the PHCs had a separate labour room and only around 61 per cent had emergency obstetric care drug kit available. About 87 per cent of the PHCs did not offer medical termination of pregnancy (MTP) services. The Community Health Centers (CHCs) were only slightly better than the PHCs.

2. Right to access child health

Birth registration: Data from NFHS-3 indicated that only a little more than 60 per cent of the births in India were registered in 2005 and the coverage of birth registration varied from as low as 17 per cent in Bihar to above 90 per cent in Gujarat, West Bengal, Himachal Pradesh, Kerala, Punjab and Tamil Nadu11. The non-registration of high proportion births in the country signifies a gross violation of the convention of the right of a child.

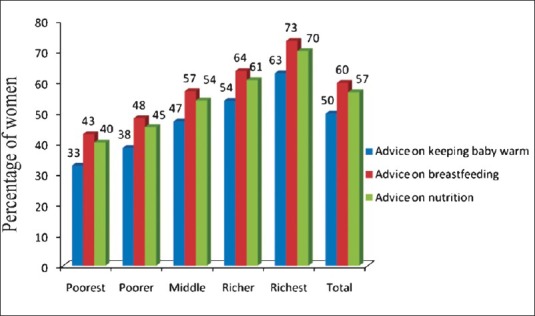

Preventive care: Fig. 2 presents the percentage of women who received advice on various components of child care during antenatal care sessions. As per the data available only 50-60 per cent of pregnant women in India were advised on the three components during antenatal sessions. Women from the richest households were almost twice more likely to have received three sets of advices compared to women from the poorest households. The prevailing disparities between the rich and the poor were even wider when data were examined with respect to child receiving any check-up within 24 h of birth. Children born to rich women were 3 times more likely to have received a check-up within 24 h of delivery as compared to the children born to poor women12.

Fig. 2.

Women receiving advice on various components of child care by wealth quintiles, India, DLHS-3.

Nearly 60 million Indian children are estimated to be underweight and more than 50 per cent suffer from anaemia26,27. Trend analysis revealed a marginal decline in % underweight from 53 per cent in 1992-1993 to 46 per cent in 2005-2006. While the percentage of underweight children came down, socio-economic inequalities remained alarmingly high with children belonging to poorest households being twice as likely as children belonging to richest households to be underweight21. A multivariate analysis by Pathak and Singh28 showed an increase in socio-economic inequalities in the last two decades.

Trends in complete immunization (includes one dose each of BCG, measles, and three doses each of DPT and polio, excluding Polio 0) also suggest a picture similar to that observed in case of new born care and malnutrition. Stark differences in receiving full set of vaccinations were noted by wealth quintile; only 24 per cent of children from poor households received full set of vaccinations compared to as high as 71 per cent from richer households. Rich-poor ratio in receiving full set of vaccinations was consistently close to 3 over the last two decades indicating that children belonging to rich households were 3 times as likely as children belonging to poor households to have received full set of vaccinations24.

Curative care: Use of ORS is one of the easiest and cost-effective interventions to manage diarrhoea and to prevent the onset of severe diarrhoea. The advantage of ORS in managing diarrhoea is lost if women or other members of the household are not aware about ORS. So, two prominent questions arise: first, are Indian women aware about ORS as an intervention to manage diarrhoea? If yes, whether women give ORS to the children when they suffer from diarrhoea? It was found that only 48 per cent of the Indian mothers were aware of ORS. Awareness ranged from 34 per cent among mothers from the poorest households to 66 per cent among mothers from the richest households. Further, only 57 per cent of the Indian women were aware about the danger signs of ARI; ranging between 47 per cent among the poorest group and 69 per cent among the richest group12.

The utilization of ORS for diarrhoea was even lower; among children who suffered from diarrhoea in last two weeks prior to survey, only 34 per cent were given ORS. There were marked variations in using ORS for managing diarrhoea by the mothers belonging to the different categories of wealth quintile; only 21 per cent among children belonging to the bottom 20 per cent of households compared to 51 per cent among children belonging to the top 20 per cent of the households.

The evidence suggested gross violation of rights of children towards achieving good health since the time of birth. Not all children were registered, only a small proportion of the children got newborn care, proper nutrition and a complete set of vaccinations, and even less than half of the children who suffered from diarrhoea received ORS. In addition, available evidence indicated towards huge differentials by wealth quintiles for all the indicators.

3. Right to access improved water and sanitation

Right to access improved water and improved sanitation is the most basic right to achieving good health and are also the basic components of the ‘right to food’ initiative29. Data from DLHS-3 suggested that only 84 per cent of the Indian households had access to improved source of drinking water. The data revealed that 93 per cent of the richest households had access to improved sources of drinking water compared to only 74 per cent of the poorest households. Only 42 per cent of the Indian households had access to improved sanitation. The variations in access to improved sanitation by wealth quintiles were marked; less than 1 per cent of the households from the poorest households had access to improved sanitation, compared with 89 per cent among richest households. More surprising was the fact that only around 50 per cent of the so called richer households (those in the fourth quintile) had access to improved sanitation.

Discussion

Evidence revealed that the enjoyment of rights of women and children towards achieving good health was extremely limited. The right to health was violated for a large number of women and children due to limited awareness of the women. Even after concerted efforts by the government and non-government organizations, the imparting of knowledge to the women to care for themselves and their children was extremely limited. The entitlement of two basic rights, i.e. right to improved drinking water and sanitation, was way far from universal. Above all, there exists enormous amount of socio-economic inequalities. The most worrying factor is that the inequalities are widening with declining averages and if the trends are to be believed, socio-economic inequalities are likely to further widen in the near future. There were huge differentials by State and region of residence. Most of the indicators discussed were poorer in the northern region of India compared to the southern region. On the other hand, socio-economic inequalities were more pronounced in the southern parts of the country. Thus, programme focus on the northern region is going to address only a part of the problem because there is significant proportions of women and children in the southern region as well whose human rights are not fulfilled. At the same time, there is a need for programme attention in the southern region to arrest the growing socio-economic inequalities. Targeting the poor may not be enough since there are also women from the rich households who also need attention.

The challenges are huge and numerous and call for immediate action. At the same time, there are enormous opportunities to address these challenges. The programme mangers and policy makers have to capitalize on these available, increasingly wider opportunities arising under the ambitious Government Sponsored Programmes like Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), Jawaharlal Nehru Urban Renewal Mission (JNURM), etc. These policies and programmes need to be tailor-made to better suit the requirements of the different segments of the population and also needs of the people living in different parts of the country. The policies, along with improving indicators, must also strive to address prevailing socio-economic inequalities.

Making men and women aware of their rights towards good sanitation and health and fulfillment of those rights are also likely to boost other sectors as well. For example, meeting the unmet need for contraceptives will not only help in arresting the population growth, but will also help in deriving a number of other benefits including overall health gains. Studies have demonstrated that if India is able to meet the unmet need of family planning in the next five years, it is likely to save nearly 150,000 maternal deaths30. Increased survival of mothers will in turn improve the survival of a large number of children during their first year of life, many of whom would have otherwise died. These benefits could be multiplied manifold if family planning services are coupled with the availability of facilities that are easily accessible to women seeking skilled birth attendance and post partum care.

It is important to mention that the ‘Right to Health Care’ approach has been the guiding framework for implementing NRHM, since it places people at the centre of the process of regularly assessing whether the health rights of the community are being fulfilled31. It is satisfying to note that some recent evaluations of NRHM suggest that strategies adopted under NRHM have started paying dividends as far as institutional deliveries are concerned25,32. Preliminary evidence suggests that more and more women, especially from economically poor households, are coming forward and are demanding maternal and child health related services from the public facilities. Most recent data from Uttar Pradesh indicates that institutional deliveries have gone up from only 20 per cent prior to launch of JSY to 44 per cent after the launch of JSY. Also, more than 60 per cent of these births took place in public facilities31. This provides a great opportunity for counselling women and their husbands about benefits of not only family planning and promotion of post partum contraception, but also about child care practices including initiation and continuation of exclusive breastfeeding up to six months, prevention and management of diarrhoea, etc. This will help to achieve ‘human right’ for all, including the last person at the bottom of the pyramid.

References

- 1.Amnesty International. Amnesty Basic Definition of Human Rights. [accessed on December 12, 2010]. Available from: http://www.amnestyusa.org/research/human-rights-basics .

- 2.James N. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Stanford: Stanford University; 2006. Human Rights. [Google Scholar]

- 3.San Francisco: United Nations; 1945. United Nations. Charter of the United Nations. 59 Stat. 1031. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freedman LP, Isaacs SL. Human rights and reproductive rights. Stud Fam Plann. 1993;24:18–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.New York: United Nations; 1968. United Nations. Final Act of the International Conference on Human Rights. A/Conf. 32/41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook RJ, Fathalla MF. Advancing reproductive rights beyond Cairo and Beijing. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 1996;22:115–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Law. Constituttion of India - Part III: Fundamental Rights. [accessed on April 8, 2013]. Available from: http://lawmin.nic.in/olwing/coi/coi-english/Const.Pock%202Pg.Rom8Fsss(6).pdf .

- 8.Wagstaff A, Claeson M. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2004. The Millenium Development goals for health: Rising to the challenges. [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Institute for Population Sciences and ORC Macro. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 1995. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-1), 1992-93: India. [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Institute for Population Sciences and ORC Macro. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2000. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), 1998-99: India. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2007. IIPS, Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06: India: Volume I & II. [Google Scholar]

- 12.District Level Household Survey (DLHS-3), 2007-08. Mumbai: IIPS; 2010. International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunt P. Geneva: United Nations General Assembly: Human Rights Council; 2010. Special Rapporteur on the Right of Everyone to the Enjoyment of the Highest Attainable Standard of Health. [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNICEF. The convention on the rights of the child - Survival and development rights: the basic rights to life, survival and development of one are full potential. [accessed on April 8, 2013]. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/crc/files/SurvivalDevelopment.pdf .

- 15.Montgomery MR, Gragnolati M, Burke KA, Paredes E. Measuring living standards with proxy variables. Demography. 2000;37:155–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data - or tears: an application to educational enrolments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38:115–32. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. DHS comparative reports no. 6. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro, MEASURE DHS; 2004. The DHS wealth index. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21:459–68. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gwatkin DR, Rutstein S, Johnson K, Suliman E, Wagstaff A, Amouzou A. Country Reports on HNP and Poverty. Washington, D.C: World Bank; 2007. Socio-economic differences in health, nutrition, and population within developing countries: an overview. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Donnell O, Doorslaer EV, Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. WBI learning resources series. Washington, D.C: World Bank; 2008. Analyzing health equity using household survey data a guide to techniques and their implementation. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howe LD, Hargreaves JR, Gabrysch S, Huttly SRA. Is the wealth index a proxy for consumption expenditure? A systematic Review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:871–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.088021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Standards for maternal and neonatal care. Geneva: WHO Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth Care (IMPAC), WHO; 2006. World Health Organization. Provision of effective antenatal care. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pathak PK, Singh A, Subramanian SV. Economic inequalities in maternal health care: prenatal care and skilled birth attendance in India, 1992-2006. PloS One. 2010;10:e13593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohanty SK, Pathak PK. Rich-poor gap in utilization of reproductive and child health services in India, 1992-2005. J Biosoc Sci. 2009;41:381–98. doi: 10.1017/S002193200800309X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, Gakidou E. India's Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet. 2010;375:2009–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deaton A, Dreze J. Nutrition in India: facts and interpretations. Econ Polit Wkly. 2009;44:42–65. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gragnolati M, Shekar M, DasGupta M, Bredenkamp C, Lee Y. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2005. India's undernourished children: a call for reform and action. Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pathak PK, Singh A. Trends in malnutrition among children in India: Growing inequalities across different economic groups. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:576–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Note on the Draft National Food Security Bill. New Delhi: National Advisory Council (NAC); 2011. National Advisory Council. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldie SJ, Sweet S, Carvalho N, Natchu UCM, Hu D. Alternative strategies to reduce maternal mortality in India: A cost-effectiveness analysis. PloS ONE. 2010;7:e1000264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.New Delhi: Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005. National Rural Health Mission (2005-2012): Mission Document. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaping demand and practices to improve family health outcomes in northern India. Policy Brief No. 1. New Delhi: Population Council; 2010. Population Council. [Google Scholar]