Abstract

Nitric oxide and cGMP modulate vascular smooth muscle cell (SMC) phenotype by regulating cell differentiation and proliferation. Recent studies suggest that cGMP-dependent protein kinase I (PKGI) cleavage and the nuclear translocation of a constitutively active kinase fragment, PKGIγ, are required for nuclear cGMP signaling in SMC. However, the mechanisms that control PKGI proteolysis are unknown. Inspection of the amino acid sequence of a PKGI cleavage site that yields PKGIγ and a protease database revealed a putative minimum consensus sequence for proprotein convertases (PCs). Therefore we investigated the role of PCs in regulating PKGI proteolysis. We observed that overexpression of PCs, furin and PC5, but not PC7, which are all expressed in SMC, increase PKGI cleavage in a dose-dependent manner in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells. Moreover, furin-induced proteolysis of mutant PKGI, in which alanines were substituted into the putative PC consensus sequence, was decreased in these cells. In addition, overexpression of furin increased PKGI proteolysis in LoVo cells, which is an adenocarcinoma cell line expressing defective furin without PC activity. Also, expression of α1-PDX, an engineered serpin-like PC inhibitor, reduced PC activity and decreased PKGI proteolysis in HEK293 cells. Last, treatment of low-passage rat aortic SMC with membrane-permeable PC inhibitor peptides decreased cGMP-stimulated nuclear PKGIγ translocation. These data indicate for the first time that PCs have a role in regulating PKGI proteolysis and the nuclear localization of its active cleavage product, which are important for cGMP-mediated SMC phenotype.

Keywords: guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase I; proprotein convertase; nitric oxide and guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate signaling

nitric oxide (NO) and cGMP play an important role in regulating vascular function and structure. In several disease models, decreased NO and cGMP signaling are associated with dedifferentiation and excessive proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMC) (9, 60), which can contribute to vasomotor instability and hypertension. In models of newborn lung disease, for example, pulmonary injury often causes decreased NO and cGMP signaling, pulmonary SMC hyperplasia, pulmonary hypertension, right heart failure, and reduced somatic growth. In such cases, selective pulmonary NO treatment has been observed to decrease abnormal pulmonary artery SMC proliferation (66, 67), improve alveolar development (4, 8, 45, 52), and prevent pulmonary hypertension (66, 67).

NO and cGMP regulate vascular SMC phenotype primarily by stimulating cGMP-dependent protein kinase I (PKGI) (10, 15, 47, 95) through mechanisms that are incompletely understood. PKGI is expressed in vascular SMC as two isoforms, PKGIα and PKGIβ, which are translated from alternatively spliced PKGI mRNA (85). These PKGI isoforms differ in their first ∼100 amino acids, which harbor a leucine zipper-like (LZ) domain (69) that directs PKGI isoform homodimerization (65) and interactions with cytosolic anchoring proteins (13, 50, 89). This amino acid region also contains an autoinhibitory (AI) domain that interacts with the substrate recognition domain in the PKGI catalytic region and thereby inhibits PKGI kinase activity in the absence of cGMP stimulation (30). The PKGI COOH-terminal region, which is identical in the PKGI isoforms, has cGMP- and ATP-binding domains and a catalytic region. The phosphorylation of cytosolic targets regulates SMC cytoskeletal activity by regulating intracellular Ca2+ levels and sensitization and possibly the thin filament (reviewed in Ref. 46).

Several studies suggest that PKGI nuclear localization is required for the regulation of gene expression and the modulation of cell phenotype by NO and cGMP. For example, PKGI has been detected in the nucleus of several cell types, including SMC (17, 28, 62). PKGI has also been shown to phosphorylate or regulate the activity of several proteins that reside primarily in the cell nucleus that modulate gene expression (60). For example, PKGI has been reported to phosphorylate and activate cAMP response-binding protein (CREB) (28, 60, 81), activating transcription factor-1 (70), TFII-I (14), and CRP4 (94) and to increase the expression of transcription regulators, such as the activator protein 1 constituents c-FOS and JunB (26, 27), growth arrest-specific homeobox gene (91), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (90). Moreover, in several cell types, nuclear PKGI translocation has been observed to be required for the regulation of gene expression by cGMP (13, 26, 28, 81). Although it is possible that cytoplasmic targets of PKGI could regulate gene expression, one study suggested that PKGI regulates nuclear signaling through mechanisms that are independent of Ca2+, cAMP-dependent protein kinase, and MAPK signaling pathways (26). However, the lack of nuclear PKGI localization and the variability in PKGI-regulated gene expression observed in some experiments (12, 16, 22, 37) and the observation of SMC dedifferentiation and proliferation in some vascular tissues with increased PKGI expression suggest that additional mechanisms might control nuclear PKGI function. Understanding what regulates nuclear PKGI translocation and activity will likely provide important insights into how NO and cGMP signaling influence health and disease.

We recently observed that PKGI proteolysis regulates PKGI nuclear localization and cGMP's regulation of gene transcription (81). PKGI epitope mapping studies in intracellular compartments and in purified subcellular protein fractions suggested that proteolysis removes the NH2-terminal LZ and AI domains in the PKGI isoforms and generates a constitutively active COOH-terminal kinase fragment, which we termed PKGIγ, that localizes in the nucleus in a variety of cell types. Moreover, scanning mutagenesis studies of the putative PKGI cleavage site and intracellular compartmentation studies revealed that PKGI proteolysis was critical for cGMP's stimulation of nuclear PKGIγ localization and the activation of CREB phosphorylation and transactivation of gene expression. However, the enzymes that regulate PKGI cleavage had not been identified. Here we report that proprotein convertases (PCs) have an important role in mediating PKGI proteolysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents.

Biotinylated monoclonal mouse anti-FLAG was obtained from Sigma (M2; F9291), monoclonal mouse anti-α-tubulin was obtained from EMD Millipore (clone AT6/172, 05-384), rabbit anti-COOH-terminal PKGI (anti-PKGICR) was obtained from Enzo (ADI-KAP-PK005), anti-furin was obtained from Pierce (PA1062), anti-V5 epitope was obtained from Sigma (V8137), and anti-insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) was from Cell Signaling (3018). Alexa Fluor 546 anti-rabbit antibody was obtained from Invitrogen (A-11035). Peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch (715-035-150 and 711-035-152, respectively). To stimulate PKGI, the membrane-permeant cGMP analog 8-(p-chlorophenylthio)-cGMP (8-pCPT-cGMP; C5438; Sigma) was used. To inhibit PCs in the aortic SMC, the membrane-permeable PC inhibitor decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-chloromethylketone (dec-RVKR-CMK; Bachem) was used.

Plasmid and adenovirus construction and characterization.

pcDNA3·PKGIβ·FLAG, which contains cDNA inserted into the BamHI-ApaI sites of pcDNA3.1 and encodes murine PKGIβ with a COOH-terminal FLAG epitope, was generated and characterized as described previously (81). pcDNA3·PKGIα·FLAG was constructed by exchanging the HindDIII-EcoRI fragment of pcDNA3·PKGIβ·FLAG with cDNA that encodes the 5′-terminal sequence of PKGIα that was generated using mouse lung mRNA, and RT-PCR. pcDNA3·PKGIβ·FLAG-δKVEVTK, which encodes PKGIβ·FLAG with alanines substituted for the KVEVTK sequence, was generated using pcDNA3·PKGIβ·FLAG and PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis as described previously (81). pSVL·furin, which encodes mature ∼87 kDa furin, was generated and characterized by Van de Ven and colleagues using a mouse cDNA library (87) and was obtained from American Type Culture collection (ATCC; 63248). pcDNA3·furin·V5 was constructed by using DNA primers (sense: c acc atg gag ctg aga tcc tgg; antisense: aag ggc gct ctg gtc ttt gat gaa ggc) and PCR to amplify the coding region of furin from pSVL·furin while adding a Kozak consensus sequence and removing the stop codon. The furin·V5 encoding cDNA was then cloned into pENTR using In-Fusion (Clontech) and subsequently inserted into pcDNA3.2·V5-DEST (Invitrogen) using recombination. pCMV·SPORT6·PC7, which contains a mammalian gene collection (MGC) clone that encodes murine PC7 (80), was obtained from ATCC (MGC-11587). pcDNA3·PC5A was constructed using a commercially available human PC5A MGC clone in pOTB7 (BC012064; Open Biosystems MHS1011-75908) by recombining the PC5A-encoding cDNA into pcDNA3.2-V5-DEST (Invitrogen) through pDONR221 (Invitrogen). DNA sequencing revealed that this clone encodes the PC5A isoform of PC5 (49). pRcCMV·α1-PDX was kindly provided by Dr. Gary Thomas (Vollum Institute, Oregon Health & Science University); the in vitro PC inhibitory activity of the encoded α1-PDX is characterized elsewhere (11, 36).

An adenovirus that encodes murine PKGIβ with a COOH-terminal FLAG epitope (Ad.PKGIβ·FLAG) was constructed in the following manner. First, PCR was used to introduce a silent mutation that deleted the PacI site in PKGIβ in pcDNA3·PKGIβ·FLAG and then the Asp718-PmeI digested fragment of the plasmid, which encodes PKGIβ·FLAG, was ligated into the Asp718-EcoRV sites of pENTR2B in the presence of 6% polyethylene glycol 8000. Next, pAd·PKGIβ·FLAG was generated using this new plasmid, pAd/CMV/V5-DEST (Invitrogen), and recombination. Finally, Ad·PKGIβ·FLAG was generated after transfecting 293A packaging cells (Invitrogen) with PacI-digested pAd·PKGIβ·FLAG using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The Ad·PKGIβ·FLAG was purified using end-point dilution (57) and characterized by detecting PKGIβ·FLAG transgene expression using M2- and anti-PKGICR antibodies and immunoblotting. The adenovirus titer was determined using the cytopathic effect assay described by O'Carroll and coworkers (58). Endonuclease mapping and automated DNA sequencing were used, when appropriate, to verify the authenticity of all the plasmid constructs.

Cell culture and transfection.

The investigations were approved by the Subcommittee for Research Animal Studies at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Rat aortic SMC were isolated using the following method that was described previously (81). Aortas from eight rats were minced, combined, and treated with type 2 collagenase (Worthington Biochem) in 10% fetal bovine serum (vol/vol; FBS HyClone SH30088.03) in DMEM supplemented with antibiotics and glutamine. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in 10% FBS DMEM supplemented with antibiotics and glutamine, allowed to seed onto cell culture plates, and then expanded. The SMC identity was confirmed based on their typical morphology and expression of α-smooth muscle actin as determined by reactivity with an antibody (1A4; Sigma) and epifluorescence microscopy, as described previously (5). The rat aortic SMC were used before reaching the eighth passage. All other cells were obtained from commercial sources: human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells (ATCC CRL-1573), and LoVo metastatic colon adenocarcinoma cells (ATCC CCL-229).

The rat aortic SMC, HEK293, and LoVo cells were maintained in DMEM; media was supplemented with 10% FBS (GIBCO), penicillin, and streptomycin. Glutamine was added to the DMEM media. The cells were passaged before becoming confluent using ETDA-trypsin. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 and methods detailed by the manufacturer.

Immunodetection of proteins and quantification of proteolysis.

The protein expression levels of PKGI and PKGIγ were detected using immunoblotting. After being washed gently with ice-cold (PBS) buffered saline, the cells were collected in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7, 4% (wt/vol) sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol and sonicated. Following centrifugation to remove insoluble material, the protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using a bicinchoninic acid-based (BCA) protein assay method (Pierce). Finally, 0.01 vol of β-mercaptoethanol and 1% (wt/vol) bromphenol blue were added, and the sample was heated to 95°C and then cooled on ice. We found that PKGIγ protein levels decreased in frozen cell lysates so PKGIγ immunoreactivity was examined soon after the samples were collected. To detect PKGI proteolysis and furin abundance, protein fractions were resolved using SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. After the protein blot was blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, it was incubated with a primary antibody and exposed to a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody before the antigen-antibody complexes were detected using chemiluminescence. In the cases in which the biotinylated anti-FLAG antibody was used to detect the FLAG epitope, the blots were exposed to complexed avidin-biotin-peroxidase (PK-6200; Vector Laboratories) instead of the secondary antibody before detection using chemiluminescence.

The percent PKGI proteolysis was quantified using immunoblot chemiluminescence. Uncalibrated chemiluminescent signals were acquired using a cooled charge-coupled camera (ChemiDoc XRS; Bio-Rad) and analyzed using ImageJ (63). The percent PKGI cleavage was determined by dividing the density of the PKGIγ-FLAG fragment by the sum of those associated with the PKGIβ·FLAG and PKGIγ-FLAG fragments, which represent the total amount of PKGI transgene expressed in the cell.

PC enzyme activity.

PC activity was determined in the cell lysates of HEK293 cells that were transfected with either pcDNA3, pSVL·furin, or pCMV·SPORT6·PC7 using Pyr-Arg-Thr-Lys-Arg-AMC (I-1650; Bachem), an internally quenched fluorogenic substrate, fluorescence spectroscopy, and methods described by others (6, 35). HEK293 cells seeded at 2 × 105 cells/cm2 in 12-well plates were transfected with 1.5 μg of plasmid using 3 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). The next day, the cells were scraped into 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 1% (vol/vol) protease inhibitors (P8340; Sigma). After sonication and centrifugation, the protein concentration was determined in soluble cell fractions using the BCA protein assay method, and 30 μg of the cell lysates were interacted with 50 μM Pyr-Arg-Thr-Lys-Arg-AMC and 2.5 mM CaCl2 in a 100-μl reaction volume. After 60 min, 10 μl of 100 mM EDTA was added to the reaction, and the samples were stored on ice to stop the reaction. The AMC released from the cleaved peptide was measured using fluorescent spectroscopy (VICTOR X3; Perkin Elmer).

PC inhibitors and nuclear PKGIγ localization.

Rat aortic SMC were seeded at 0.25 × 105 cells/cm2 in glass bottom chamber slides in 10% FBS DMEM containing antibiotics and supplemental glutamine. The following day, the cells were briefly washed with 0.1% FBS DMEM containing antibiotics and supplemental glutamine, and then the media was exchanged with media containing 0 or 50 μM dec-RVKR-CMK. After overnight incubation, the cells were treated to a fresh aliquot of the solutions with and without dec-RVKR-CMK and 200 μM 8-pCPT-cGMP for an additional 2 h. This level of dec-RVKR-CMK has been reported to inhibit PC activity in several cell types for several hours without causing appreciable toxicity (38, 59, 78). Nuclear PKGIγ was detected using the following method. The cells were gently washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in buffered PBS for 15 min, and then the nuclei were permeabilized by treating the cells with methanol for 10 min. After blocking with 1% goat serum in PBS for 1 h, the cells were exposed to rabbit anti-PKGICR diluted in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and incubated at 4°C overnight. After being washed with PBS, the cells were exposed to Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes) for 1 h and then PBS containing 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole before being mounted under a glass cover slip. Nuclear COOH-terminal PKGI immunoreactivity was then detected using laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSMS Pascal; Zeiss) with the pinhole set to sample a <2-μm-thick slice through the center of the nucleus.

Data analysis.

The hydrophobicity plot was generated using the predicted amino acid sequence flanking putative scissile amino acid-bond site in murine PKGI using the method detailed by Grantham (25) and implemented by ProtScale (24).

Experiments were repeated at least three times, and typical data are shown. Numerical data are represented as means ± SD. Enzyme activity data were compared using a one-way model of ANOVA; a Tukey range test was used post hoc. Significance was determined at P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using R (34).

RESULTS

PKGI isoforms encode a minimum PC consensus recognition site in the putative cleavage area that is adjacent to the NH2-terminal portion of PKGIγ.

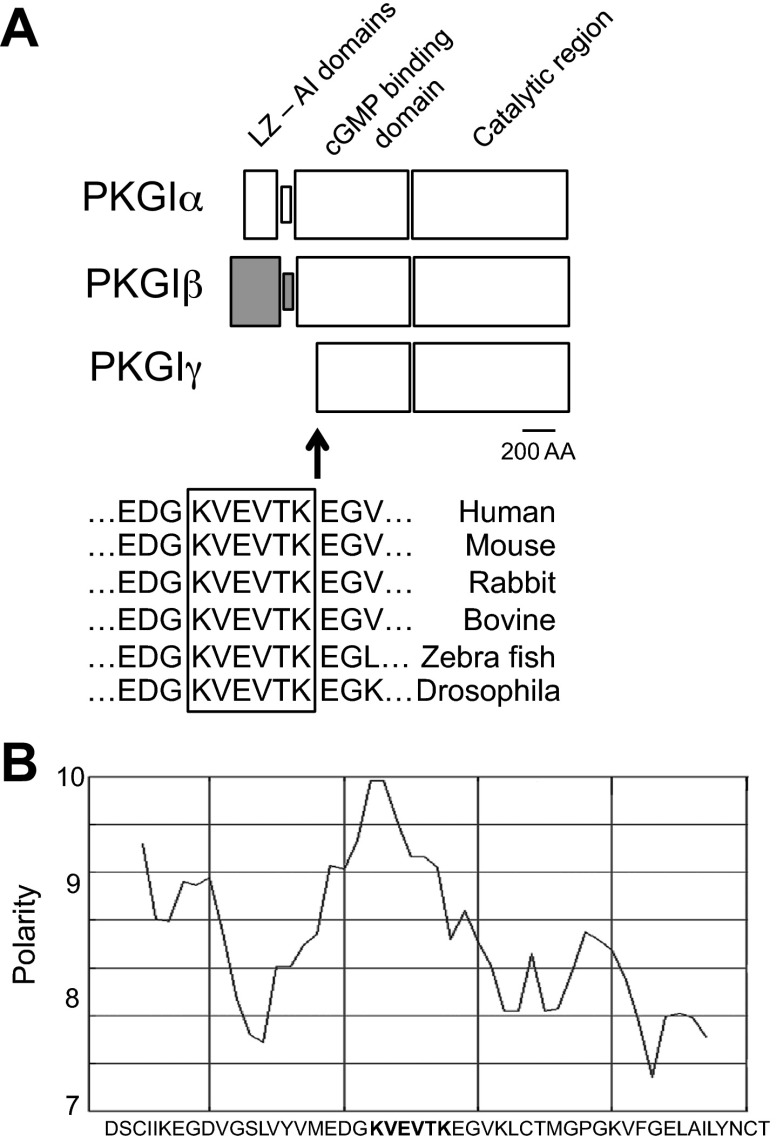

To gain insight into candidate protease recognition sites in PKGI, we previously performed amino acid microsequencing of PKGIγ that was immunopurified from nuclei of SMC (81). Although it was not possible to obtain unambiguous amino acid sequence information, the data obtained from one immunopurified protein fragment suggested that PKGI is cleaved at a scissile amino acid bond that is COOH-terminal to the amino acid sequence KVEVTK. The relationship between this sequence and the functional domains of the PKGI isoforms and PKGIγ is depicted in Fig. 1A. This site resides within the cGMP-binding domain, which is identical in the PKGI isoforms, and is COOH-terminal to a PKGIα and PKGIβ hinge region that is depicted in the figure as the narrow box between the LZ and AI domains (LZ-AI domains) of PKGIα and PKGIβ. This hinge region has been reported to be sensitive to in vitro proteolysis (55, 84). Recent PKGI crystal-structure studies indicated that this cleavage site resides in a portion of amino acids in PKGI that form a beta-sheet that projects into the extramolecular milieu (40). It is likely that this molecular configuration makes the PKGI KVEVTK domain accessible to proteases. Moreover, the potential importance of this putative protease recognition sequence is supported by analysis of PKGI amino acid sequence data obtained from the NCBI database that reveals that this site is conserved in diverse species (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Structural characterization of a putative proprotein convertase (PC) cleavage site in cGMP-dependent protein kinase I (PKGI). A: PKGIα and PKGIβ isoforms and cleaved PKGIγ share COOH-terminal functional domains that are defined in the text. PKGIγ-fragment amino acid sequencing suggested that PKGI is cleaved following KVEVTK, after residue 152 in PKGIα and 167 in PKGIβ. This sequence corresponds to a typical PC recognition site: (K/R)-Xn-(K/R), where n = 0, 2, 4, or 6 and X is not a cysteine. The putative PC recognition site in PKGI, shown in the box, resides in the cGMP-binding domain area and is conserved in many species. Cleavage at this site would result in an ∼60-kDa PKGI fragment. LZ, leucine zipper-like; AI, autoinhibitory. B: polarity map in PKGI in the putative cleavage and PC recognition site, which is in bold, supports the possibility that this site might bind to charged amino acid residues in the active cleft of PCs. The polarity scale was defined by Grantham (25).

Interrogation of a proteolytic enzyme database (64) suggested that the putative PKGI cleavage site that we identified is recognized by PCs. This is because the PKGI amino acid sequence predicted to reside NH2-terminal to the detected cleavage site is of the form (K/R)-Xn-(K/R), where n = 0, 2, 4, or 6 and X is any amino acid but not generally C, which usually directs PC-mediated substrate cleavage (72). PCs are a family of Ca2+-dependent proteases that are expressed in several cell types. PC members include furin, PC1/3, PC2, PC4, PC5, PACE4, and PC7, all of which cleave proteins at a scissile bond that is COOH-terminal to basic amino acids, and subtilisin kexin isoenzyme-1 and PCSK9, which are involved in fatty acid metabolism (3, 74, 86). PCs proteolyze and activate a variety of proteins that regulate angiogenesis and the response of SMC to vascular injury. Furin (31), and likely the other homologous PCs (32), contains a negatively charged substrate binding/catalytic pocket that interacts with basic residue-rich amino acid sequences in target proteins. As depicted in Fig. 1B, PKGI has several basic residues in the putative cleavage site that increase protein polarity and might facilitate the interaction between PKGI and the PC catalytic domain.

PC overexpression is associated with increased PKGI proteolysis.

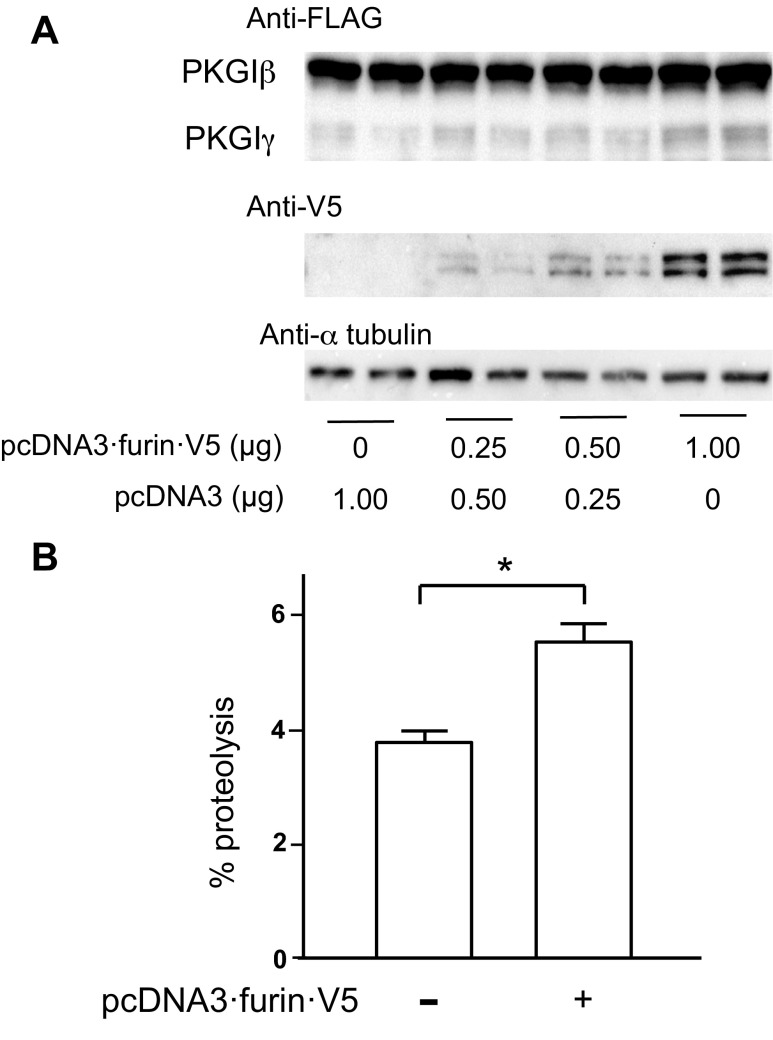

Because furin is a prototypical PC that is widely expressed in cells and whose proteolytic activity is well defined, we first tested whether or not furin overexpression increases PKGI proteolysis. We used HEK293 cells as a model system for these experiments because in pilot studies we observed PKGI proteolysis in these cells, which suggests that they have functional systems that facilitate PKGI transport to the protease-containing compartment, and because these cells are readily transfected. We examined the cleavage of COOH-terminal FLAG epitope-tagged PKGI isoforms because the sensitivity and specificity of the FLAG-detection system allowed us to detect steady-state levels of PKGIγ, and thereby PKGI proteolysis, without needing to expose the cells to radiochemicals. For these studies, we studied primarily the proteolysis of the PKGIβ isoform because PKGIβ was better expressed than PKGIα in this experimental model, and, as noted before (81), PKGIβ proteolysis is often more readily detected in cells.

Overexpression of furin increased PKGI proteolysis. HEK293 cells transfected with pcDNA3·PKGIβ·FLAG exhibited a low level of PKGIβ·FLAG proteolysis in soluble cell lysates examined with immunoblotting and an anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 2A). This is shown by the detection of an ∼60-kDa protein band with anti-FLAG antibody immunoreactivity that migrates faster in the polyacrylamide gel than the ∼78-kDa protein species detected with the antibody that has a molecular mass consistent with uncleaved PKGIβ·FLAG. No bands with anti-FLAG immunoreactivity were detected in the lysates of cells transfected with control plasmids (data not shown). The ∼60-kDa molecular mass protein was similar in size to the only PKGI fragment that we identified previously in the nuclei of vascular SMC and PKGI-expressing cell lines (81). This nuclear PKGI fragment was determined to be a COOH-terminal PKGI fragment using differentiation antibody epitope mapping and amino acid microsequencing, and was defined as PKGIγ (81). Importantly, transfection of the HEK293 cells with a plasmid that encoded a furin transgene with a COOH-terminal V5 tag (pcDNA3·furin·V5) caused a nearly 50% increase in the levels of this PKGI cleavage product (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Furin overexpression increases PKGI proteolysis. Separate cultures of human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were transfected with 1 μg of plasmids that encode murine PKGIβ with a COOH-terminal FLAG tag and either human furin with a COOH-terminal V5 tag or a control plasmid, pcDNA3. The next day, soluble protein fractions were obtained, and steady-state PKGIβ proteolysis was detected using an anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotting. Anti-V5 antibody revealed furin·V5 expression; α-tubulin immunoreactivity was used as a loading control. A and B: furin overexpression was associated with increased PKGIβ proteolysis. Cells overexpressing furin had increased amounts of an ∼60-kDa fragment with FLAG immunoreactivity, similar to previously described PKGIγ. B: densitometry revealed that furin overexpression increased PKGIβ proteolysis nearly 50%; n = 3 each group, *P < 0.05.

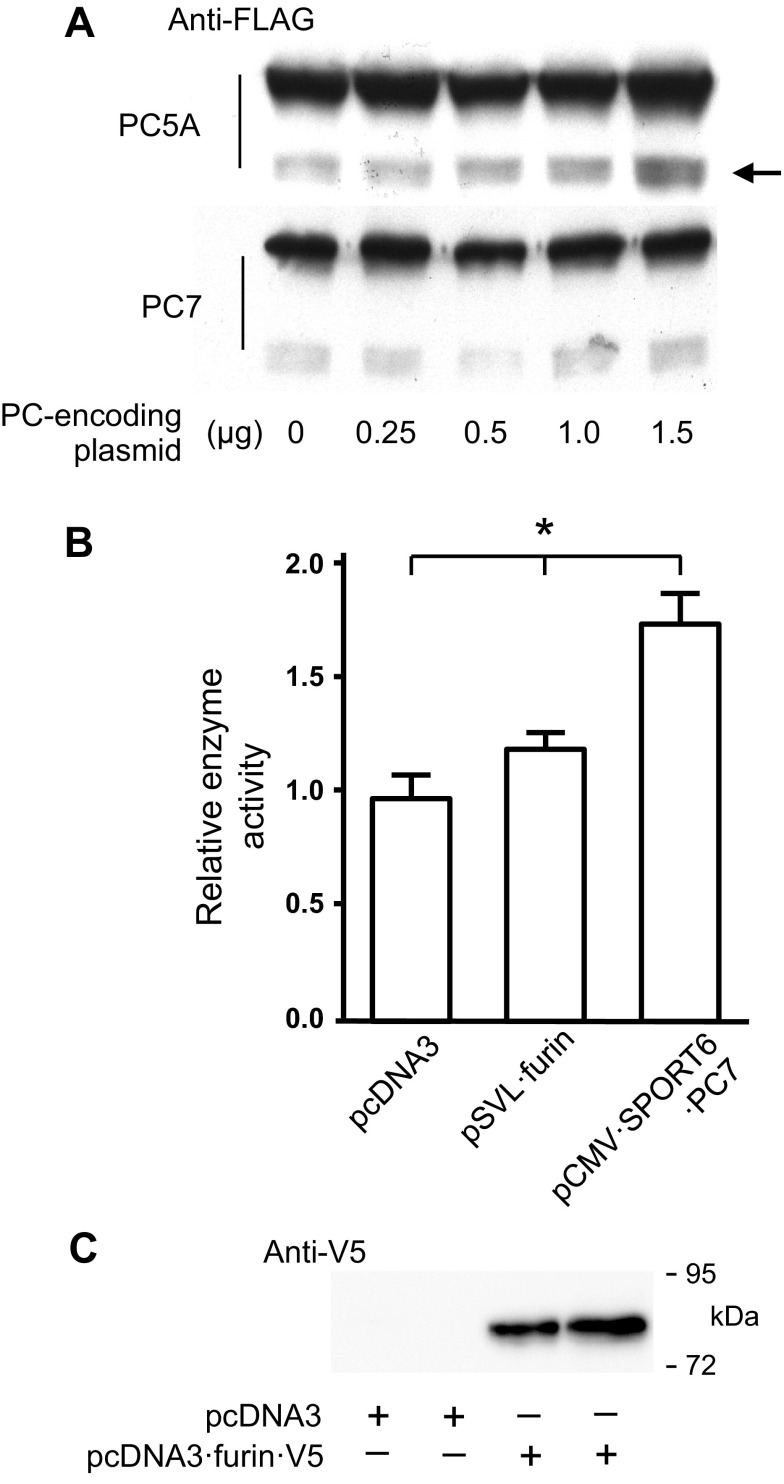

Although PCs often exhibit functional redundancy, in some cases they do not share the same protein targets and thereby may proteolyze target proteins differently. PC-substrate specificity is influenced by differences in substrate affinity and by the colocalization of PCs and protein targets. PC5, PC7, and furin are all expressed in vascular SMC (77, 79). PC5 is expressed as two isoforms, PC5A and PC5B (also referred to as PC6A and PC6B), that result from the alternate splicing of PC5 mRNA (56). PC5A (but not PC5B) expression is modulated by injury in vascular SMCs (79). Because of the expression pattern of these PCs, we tested whether PC5A and PC7 overexpression is associated with increased PKGI proteolysis. As shown in Fig. 3A, cotransfection of HEK293 cells with plasmids that encode PKGIβ·FLAG and increasing amounts of PC5A was associated with a dose-dependent increase in PKGIγ·FLAG immunoreactivity. In contrast, transfection of cells with a PC7-encoding plasmid (pCMV·SPORT6·PC7) did not increase PKGI cleavage. To examine whether proteolytic activity was increased in this PC overexpression model, HEK293 cells were transfected with pCMV·SPORT6·PC7, pSVL-furin, or a control plasmid, and PC activity was examined in cell lysates using an internally quenched PC substrate probe. We observed that transfection with the PC7-encoding plasmid led to nearly a 1.5-fold increase in PC activity, suggesting that active PC7 was expressed from this plasmid (PC activity, arbitrary units: pcDNA3 transfected 7,581 ± 554 vs. pCMV·SPORT6·PC7 transfected 10,675 ± 903, n = 6 each group, P < 0.05; Fig. 3B). Moreover, we confirmed that active furin was expressed from the pSVL·furin plasmid. The relatively low level of cell lysate PC activity observed in the furin-overexpressing cells might be because of secretion of some of the furin into the tissue culture media (88) or possibly reduced furin pro-segment-mediated activation of the encoded mature furin (1). As shown in Fig. 3C, and in agreement with data from others (61), transfection of cells with furin-encoding plasmids results in the secretion of a proteolyzed furin fragment (“shed furin”) in the cell culture media.

Fig. 3.

PC5 also proteolyzes PKGI. A: HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of plasmids that encode PC5A or PC7 and with 1 μg of pcDNA3·PKGIβ·FLAG. The total amount of transfected DNA was normalized using control plasmids. PKGI proteolysis was detected using an anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotting. Whereas exposure to increased amounts of a PC5A-encoding plasmid increased the levels of the immunoreactive PKGIγ·FLAG fragment (arrow), transfection with the PC7-encoding plasmid did not increase the detected amount of this PKGI cleavage product. B: to confirm that active PC7 was expressed following transfection, PC enzyme activity was determined using an internally quenched PC-substrate fluorogenic probe and lysates of HEK293 cells transfected with 1.5 μg of the indicated plasmids. Transfection with the PC7-encoding plasmid used in the experiment detailed in A increased PC enzyme activity in the cell lysates; n = 6 each group, *P < 0.05 vs. each other. C: HEK293 cells were transfected with 1.5 μg of pcDNA3 or pcDNA3·furin·V5, and, the following day, proteins were precipitated from the cell media, resolved using SDS-PAGE, and electroblotted to a membrane, and shed furin·V5 was detected using an anti-V5 antibody. Cells transfected with furin-encoding plasmid secreted cleaved furin into the cell media.

Mutation of a minimum PC recognition site decreases PKGI proteolysis.

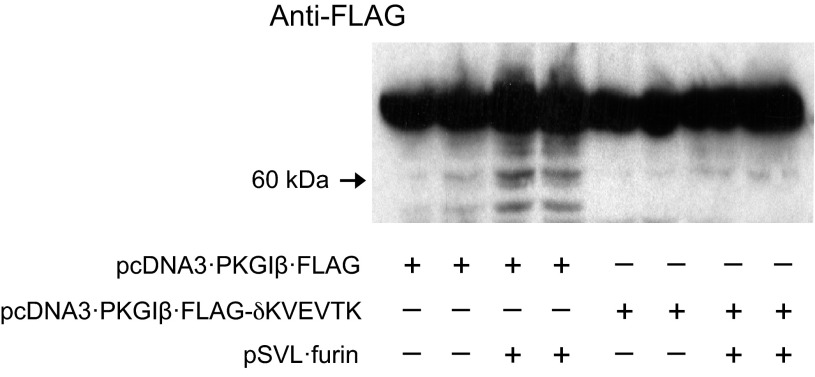

Using alanine-stretch scanning mutagenesis, we previously observed that amino acids in the putative PKGI cleavage area regulated nuclear PKGIγ translocation and gene transactivation in SMC (81). To define the role of the putative PC consensus sequence in directing PC-regulated PKGI proteolysis, we examined whether furin cleaves PKGIβ·FLAG-δKVEVTK, which is generated by plasmid that harbors mutations that encode alanines instead of the KVEVTK sequence. In pilot studies using immunoblotting, we observed PKGIβ·FLAG-δKVEVTK had approximately the same molecular weight and in vivo kinase activity (measured by ability to phosphorylate VASP) as PKGIβ·FLAG (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 4, overexpression of PKGI and mutant PKGI was associated with a minor level of proteolysis. However, we observed that increased cleavage of wild-type PKGIβ·FLAG with furin overexpression was not observed in cells expressing PKGIβ·FLAG-δKVEVTK and the PC. These studies support the role of the KVEVTK consensus sequence in directing PKGI proteolysis by PCs. It is also interesting to note that overexpression of PKGIβ·FLAG was associated with the generation of an ∼50-kDa fragment with FLAG immunoreactivity. We do not know the identity of this protein fragment; however, its apparent molecular weight suggests that it might be a further cleavage product of PKGI.

Fig. 4.

Definition of the PC proteolysis site in PKGI. HEK293 cells were transfected with 1 μg of plasmids that encode PKGIβ·FLAG with and without an alanine-substitution mutation in the putative PC recognition domain, e.g., δKVEVTK; control plasmids were used to balance the amount of transfected DNA. Steady-state PKGI proteolysis was assessed using an anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotting. Although PKGIβ·FLAG proteolysis was increased in cells with furin overexpression, the proteolysis of PKGIβ·FLAG with a mutation in the putative PC recognition domain was not increased in those overexpressing furin.

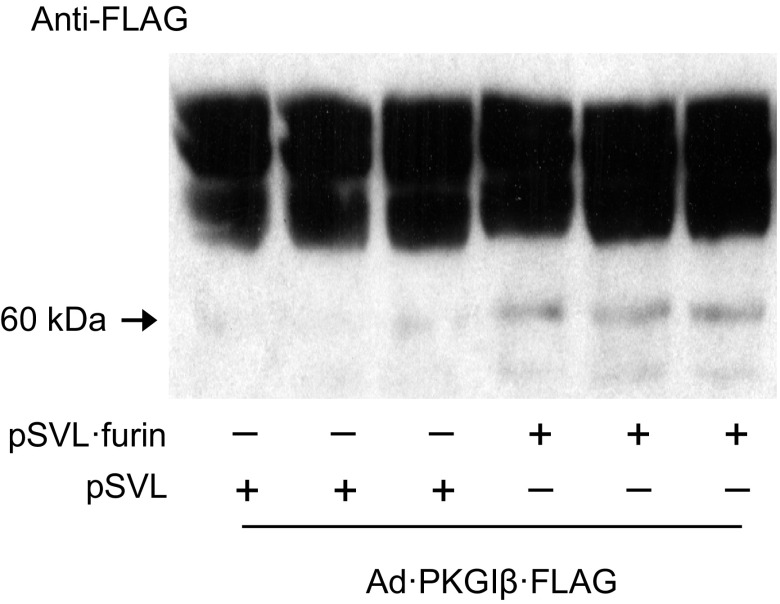

Furin overexpression increases PKGI proteolysis in furin-deficient cells.

LoVo cells are a human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (20) that expresses furin with mutations in the homo B domain and therefore has deficient furin activity (82, 83). Previous investigators have used LoVo cells to test whether furin overexpression rescues cleavage of putative PC protein targets (e.g., see Ref. 43). Accordingly, to further examine the role of PCs in PKGI proteolysis, we tested whether furin overexpression increases PKGI cleavage in LoVo cells. Because LoVo cells were difficult to cotransfect, they were first infected with an adenovirus that encoded PKGIβ·FLAG and later transfected with furin-encoding or control plasmids. As shown in Fig. 5, despite overexpressing PKGIβ·FLAG at high levels, little PKGI proteolysis was detected in LoVo cells using an anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotting. Nevertheless, a small level of PKGI proteolysis was observed in the LoVo cells, probably because they express other functional PCs (41, 73). Importantly, PKGIβ·FLAG proteolysis was increased in LoVo cells transfected with pSVL-furin. These data support the role of furin in directing PKGI proteolysis in cells.

Fig. 5.

Furin overexpression increases PKGIβ proteolysis in cells with dysfunctional furin. LoVo cells were infected with 200 multiplicity of infection of an adenovirus that encodes PKGIβ·FLAG and then transfected with or without 4.5 μg of a plasmid that encodes furin (pSVL·furin) or empty vector (pSVL). PKGI proteolysis was detected (arrow) in soluble cell lysates using an anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotting. Overexpression of furin increased PKGIβ·FLAG proteolysis in cells with deficient endogenous furin.

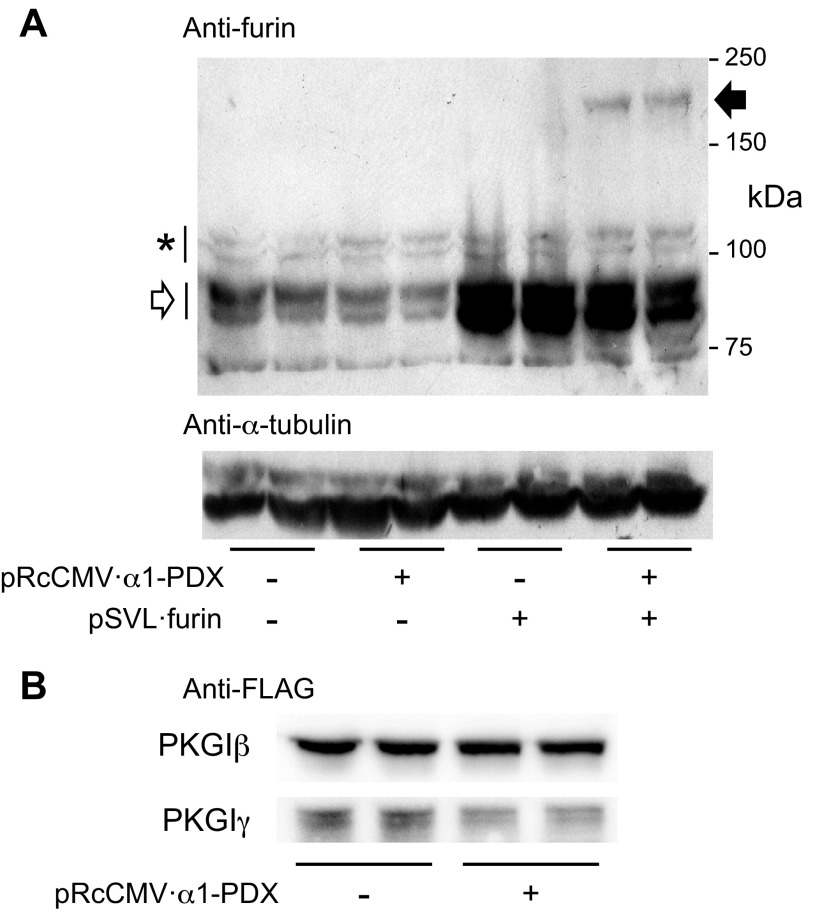

PC inhibition decreases PKGI proteolysis.

α1-PDX is a serpin-like α1-antitrypsin Pittsburgh mutant that was engineered to contain a furin consensus recognition sequence (2). In a variety of cells, α1-PDX binds tightly to the furin catalytic site and inhibits its endoproteolytic activity [IC50 = 0.6 nM (2)]. The furin-α1-PDX complex is stable during SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the level of this complex detected using immunoblotting corresponds with the extent of α1-PDX-mediated furin inhibition (36). α1-PDX also inhibits other PCs (19); the level of α1-PDX-inhibited PC activity depends on the cells studied (7). To test whether α1-PDX decreases PC proteolytic activity in our model system, we examined whether transfection of HEK293 cells with an α1-PDX-encoding plasmid (pRcCMV·α1-PDX) inhibits autoproteolysis of endogenous profurin and forms an inhibitory complex with overexpressed mature furin. As shown in Fig. 6A, α1-PDX partially inhibits endogenous furin activity, and it also forms an SDS-stable complex with overexpressed furin in HEK293 cells. With α1-PDX expression, the steady-state level of endogenous profurin (Fig. 6A) was increased, whereas that of the autoproteolyzed mature furin product was decreased. The anti-furin antibody-reactive doublets are glycosylated forms of profurin and furin that have been described by others (29). Although immunoblotting did not detect an SDS-stable α1-PDX complex with endogenous furin, an α1-PDX-furin complex was observed in lysates of cells in which mature furin was overexpressed. These studies support the use of α1-PDX to inhibit furin activity in HEK293 cells. Importantly, we observed that α1-PDX caused a decrease in PKGIβ·FLAG proteolysis in HEK293 cells cotransfected with pRcCMV·α1-PDX and pcDNA3·PKGIβ·FLAG (Fig. 6B). The level of PKGIγ-FLAG immunoreactivity was decreased in the lysates of cells transfected with the α1-PDX-encoding plasmid. These studies support the role of PCs in regulating PKGI proteolysis.

Fig. 6.

PC inhibition decreases PKGI proteolysis in cells. Cells were transfected with plasmids that encode α1-PDX, an inhibitor of PC activity, PKGI isoforms with a COOH-terminal FLAG tag, or control plasmids. Later, soluble proteins in cell lysates were denatured and resolved using gel electrophoresis and transferred to a charged membrane for immunoblotting. In some experiments, furin and a furin-α1-PDX complex were detected with an anti-furin antibody. In others, PKGI proteolysis was detected using an anti-FLAG antibody. A: HEK293 cells express profurin (*) and mature furin (open arrow), which results from profurin autoproteolysis, and associated N-glycosylated species. Transfection with pSVL·furin increased the level of the encoded mature ∼85-kDa furin protein. Coexpression of α1-PDX and furin caused the formation of a higher-molecular-weight anti-furin antibody-reactive band (closed arrow) that is indicative of the formation of an α1-PDX-furin complex and PC inhibition. Similar α-tubulin immunoreactivity showed equal protein transfer. B: in HEK293 cells overexpressing PKGIβ·FLAG, transfection with the α1-PDX-encoding plasmid caused inhibition of PKGIβ transgene proteolysis and PKGIγ generation.

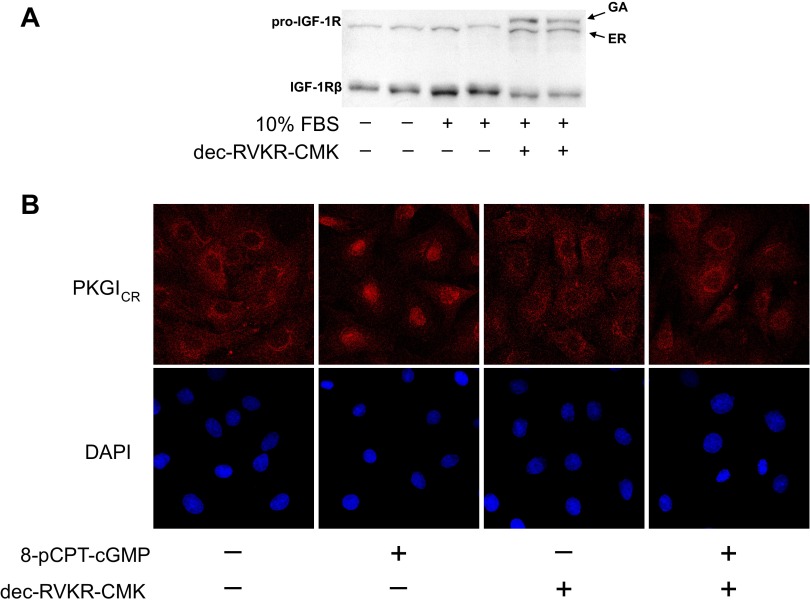

Membrane-permeable PC inhibitors decrease proteolysis-dependent PKGIγ translocation.

To examine the functional significance of PC-mediated PKGI cleavage observed in studies detailed above, we tested whether PC inhibition decreases proteolysis-dependent nuclear PKGIγ localization in rat aortic SMC. For these studies, we employed the widely used membrane-permeable PC inhibitor dec-RVKR-CMK (38, 39, 53, 78). First, we tested whether dec-RVKR-CMK inhibits PC activity in our model system by determining whether it decreases serum-stimulated pro-IGF-IR proteolysis. As shown in Fig. 7A, in the lysates of serum-starved SMC, the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) form of pro-IGF-IR and the cleaved β-subunit of IGF-IR (IGF-IRβ) were observed using an antibody against the COOH-terminal portion of IGF-IR and immunoblotting, whereas the slower-migrating Golgi apparatus (GA) form of pro-IGF-IR, which is cleaved by PCs residing in the GA, was not detected. Moreover, with serum stimulation, the amount of IGF-IRβ was increased, whereas there was no change in the abundance of the ER form of pro-IGF-IR, indicating that serum stimulated the production of pro-IGF-IR, which was fully cleaved by GA PCs. However, in the serum-stimulated SMC, dec-RVKR-CMK treatment inhibited PCs and caused the accumulation of the GA form of pro-IGF-IR and a decreased abundance of IGF-IRβ. Others (78) have described a similar degree of dec-RVKR-CMK-mediated PC inhibition of pro-IGF-IR cleavage in vascular SMC.

Fig. 7.

PC inhibition decreases PC activity and proteolysis-dependent nuclear PKGIγ localization in vascular SMC. A: rat aortic SMC were serum starved and then treated in media containing 10% FBS with and without 50 μm decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-chloromethylketone (dec-RVKR-CMK), a membrane-permeable PC inhibitor. Subsequently, COOH-terminal insulin-like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) immunoreactivity was detected in cell lysates using a specific antibody and immunoblotting. Whereas the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) form of pro-IGF-IR and cleaved IGF-IRβ was detected in all cell lysates, the latter being increased with serum stimulation, the Golgi apparatus (GA) form of uncleaved pro-IGF-IR was detected in cells treated with dec-RVKR-CMK. B: rat aortic smooth muscle cells were pretreated with and without 50 μM dec-RVKR-CMK and then with and without the inhibitor and 200 μM 8-(p-chlorophenylthio)-cGMP (8-pCPT-cMP), a membrane-permeable cGMP analog. Endogenous PKGI immunoreactivity was detected using an antibody that binds to the COOH-terminal PKGI domain (PKGCR), a fluorescently tagged secondary antibody, and laser-scanning confocal microscopy with optical sections through the cell nucleus. Proteolysis-dependent nuclear PKGIγ translocation stimulated by 8-pCPT-cGMP was inhibited by treatment with dec-RVKR-CMK.

Importantly, dec-RVKR-CMK was observed to decrease nuclear PKGIγ localization in cGMP-stimulated rat aortic SMC (Fig. 7B). In these studies, the SMC were treated with a membrane-permeable cGMP (8-pCPT-cGMP) because this has been observed to increase PKGI cleavage (81) and the fraction of cells with nuclear PKGI localization (13, 28, 81). Moreover, to localize cleaved PKGIγ in the nuclear compartment, anti-COOH-terminal PKGI immunoreactivity was detected in cell sections that transect the nucleus using laser scanning confocal microscopy. In these studies, whereas treatment of rat aortic SMC with dec-RVKR-CMK alone did not modulate nuclear PKGI immunoreactivity, exposure to the PC inhibitor decreased cGMP-stimulated nuclear PKGIγ localization in many of the cells. Because previously PKGI proteolysis was observed to be critical for nuclear PKGIγ compartmentation (81), the results detailed here suggest that PC activity plays an important role in processes that regulate nuclear PKGI localization.

DISCUSSION

The objective of this investigation was to identify mechanisms that regulate PKGI proteolysis and nuclear localization. Inspection of a likely cleavage site in PKGI and protease database interrogation (64) revealed an amino acid sequence in PKGI isoforms that is reminiscent of a PC minimum consensus sequence (72) and is conserved in several species. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that PCs modulate PKGI proteolysis in cells. We observed that overexpression of furin or PC5, but not of PC7, increases PKGI cleavage. Using furin as a prototypical PC and PKGI with mutations in the putative PC consensus sequence, we demonstrated that amino acids just NH2-terminal to the putative PKGI proteolysis site are required for its cleavage. In addition, we observed that PKGI proteolysis was increased by overexpression of furin in an adenocarcinoma cell line that has defective furin and decreased when PC activity was inhibited by expression of α1-PDX. Last, in testing the role of PCs in regulating nuclear PKGI function in vascular SMC, we observed that exposure to a membrane-permeable peptide-based PC inhibitor inhibited proteolysis-dependent nuclear localization of PKGIγ in early passage vascular SMC. Overall, these data indicate that PCs play an important role in regulating PKGI proteolysis and nuclear translocation in cultured cells.

The investigations detailed here provide new insights into key mechanisms that determine how cGMP regulates SMC phenotype. Following the studies by Garg and Hassid, which indicated that NO and cGMP decrease vascular SMC proliferation (23), much work has been devoted to elucidating the intracellular pathways through which these molecules modulate SMC phenotype. Several lines of evidence suggest that PKGI mediates the effects of NO and cGMP on cell phenotype (47). Studies indicate that cells that are deficient in PKGI, such as baby hamster kidney fibroblast (BHK) cells, and highly passaged vascular SMC acquire an undifferentiated and proliferative phenotype, whereas those in which PKGI activity is stimulated or reconstituted, such as some low-passage vascular SMC stimulated with cGMP, 3T3 fibroblasts, BHK cells, and highly passaged vascular SMC in which PKGI is expressed from plasmids or adenoviruses, appear more differentiated and less proliferative. The relationship between PKGI expression and vascular SMC phenotype has been further demonstrated in studies in which the decrease in differentiation protein markers, such as smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, vimentin, and calponin in vascular SMC with diminished PKGI expression or activity, was reversed by overexpression of PKGI (93–95). These studies have stimulated intensive efforts to identify mechanisms through which PKGI regulates cell phenotype.

The observation that PCs differentially regulate PKGI proteolysis provides insight into potential mechanisms through which they might regulate nuclear cGMP signaling. PCs exhibit substrate specificity that is based on their subcellular colocalization with and relative affinity for target proteins. Furin, PC5, and PC7 harbor a COOH-terminal transmembrane domain and a cytosolic tail that regulate their residence in the ER, GA, cytosol, and cell surface. Although active furin (11, 54) and PC5 (18) have been observed in the GA, the majority of active PC7 does not reside in that compartment. PC7 has been observed to transit from the ER directly to the plasma membrane through non-COPI-coated vesicles (68). We noted that PKGI is cleaved by furin and PC5A but not PC7. It is possible that PC7 does not cleave PKGI because plasma membrane-bound PC7 does not encounter PKGI. Also, it is possible that the catalytic domain of PC7 does not have a high affinity for PKGI. Contrasting substrate affinity between furin and PC5 and PC7 has been observed by others. For example, one study found that integrin pro-α-subunits are cleaved by furin and PC5A but not PC5B and PC7 (48). The mechanisms regulating differential PKGI proteolysis by PCs warrant further investigation.

The studies detailed here support accumulating evidence that PCs play an important role in vascular biology during health and disease (3). GA fragmentation has been observed in pulmonary arterial lesion cells isolated from animals with monocrotaline-induced lung injury (71) and from patients with idiopathic pulmonary hypertension (42). However, whether the GA disruption observed in these models inhibits proteolytic processing of proteins by GA-resident PCs has not been determined. Recent data suggest that PCs play an important role in vascular homeostasis. PCs activate several growth factors, including transforming growth factor beta-1 (21), endothelin-1, platelet-derived growth factor-B (76), and vascular endothelial growth factor-C (75), as well as extracellular matrix proteins (39) and metalloproteinases (51, 92) that have critical roles in regulating blood vessel assembly and function. Moreover, abnormalities in PC function might contribute to vascular disease. Genetic variations in furin and PC5 have been linked to hypertension and dyslipidemias (33, 44). Furin, PC5, and PC7 are detected in vascular SMC (79), and it is possible that vascular injury disrupts not only intracellular localization of PC but also their endoproteolytic function and regulation of signaling systems such as those involving PKGI.

The mechanisms through which PCs modulate PKGI proteolysis require further investigation. For example, although the GA-resident PCs furin and PC5 appear to have a role in PKGI proteolysis, it is not known whether PKGI translocation to the GA is required for PKGI proteolysis. In addition, the mechanisms regulating how PKGI traffics to the GA and how PKGIγ leaves this organelle and enters the nucleus are not defined at this time. The identification of PCs as critical regulators of PKGI proteolysis and nuclear translocation provides a starting point for in-depth investigation of the mechanisms that regulate PKGI and PKGIγ transport and topology.

In summary, we identified PCs as critical mediators of PKGI proteolysis and nuclear translocation in cultured cells. These findings support an important role for PCs in regulating nuclear cGMP signaling and SMC phenotype specification.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-094608, the MGH Executive Committee for Research, and Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.K., R.Z., and J.D.R. conception and design of research; S.K., R.Z., and J.D.R. performed experiments; S.K., R.Z., and J.D.R. analyzed data; S.K., R.Z., and J.D.R. interpreted results of experiments; S.K., R.Z., and J.D.R. prepared figures; S.K., R.Z., and J.D.R. edited and revised manuscript; S.K., R.Z., and J.D.R. approved final version of manuscript; J.D.R. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gary Thomas (Vollum Institute-Oregon Health & Science University) for generously providing the plasmid that encodes α1-PDX.

Present address of R. Zhang: Cancer Center, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, People's Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anderson ED, Molloy SS, Jean F, Fei H, Shimamura S, Thomas G. The ordered and compartment-specfific autoproteolytic removal of the furin intramolecular chaperone is required for enzyme activation. J Biol Chem 277: 12879–12890, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anderson ED, Thomas L, Hayflick JS, Thomas G. Inhibition of HIV-1 gp160-dependent membrane fusion by a furin-directed alpha 1-antitrypsin variant. J Biol Chem 268: 24887–24891, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Artenstein AW, Opal SM. Proprotein convertases in health and disease. N Engl J Med 365: 2507–2518, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Auten RL, Mason SN, Whorton MH, Lampe WR, Foster WM, Goldberg RN, Li B, Stamler JS, Auten KM. Inhaled ethyl nitrite prevents hyperoxia-impaired postnatal alveolar development in newborn rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 291–299, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bachiller PR, Nakanishi H, Roberts JD., Jr Transforming growth factor-beta modulates the expression of nitric oxide signaling enzymes in the injured developing lung and in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L324–L334, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Basak A, Chen A, Majumdar S, Smith HP. In vitro assay for protease activity of proprotein convertase subtilisin kexins (PCSKs): an overall review of existing and new methodologies. Methods Mol Biol 768: 127–153, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Benjannet S, Savaria D, Laslop A, Munzer JS, Chretien M, Marcinkiewicz M, Seidah NG. Alpha1-antitrypsin Portland inhibits processing of precursors mediated by proprotein convertases primarily within the constitutive secretory pathway. J Biol Chem 272: 26210–26218, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bland RD, Albertine KH, Carlton DP, MacRitchie AJ. Inhaled nitric oxide effects on lung structure and function in chronically ventilated preterm lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172: 899–906, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bloch KD, Ichinose F, Roberts JD, Jr, Zapol WM. Inhaled NO as a therapeutic agent. Cardiovasc Res 75: 339–348, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boerth NJ, Dey NB, Cornwell TL, Lincoln TM. Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase regulates vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. J Vasc Res 34: 245–259, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bresnahan PA, Leduc R, Thomas L, Thorner J, Gibson HL, Brake AJ, Barr PJ, Thomas G. Human fur gene encodes a yeast KEX2-like endoprotease that cleaves pro-beta-NGF in vivo. J Cell Biol 111: 2851–2859, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Browning DD, Mc Shane M, Marty C, Ye RD. Functional analysis of type 1alpha cGMP-dependent protein kinase using green fluorescent fusion proteins. J Biol Chem 276: 13039–13048, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Casteel DE, Zhang T, Zhuang S, Pilz RB. cGMP-dependent protein kinase anchoring by IRAG regulates its nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity. Cell Signal 20: 1392–1399, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Casteel DE, Zhuang S, Gudi T, Tang J, Vuica M, Desiderio S, Pilz RB. cGMP-dependent protein kinase I beta physically and functionally interacts with the transcriptional regulator TFII-I. J Biol Chem 277: 32003–32014, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chiche JD, Schlutsmeyer SM, Bloch DB, de la Monte SM, Roberts JD, Jr, Filippov G, Janssens SP, Rosenzweig A, Bloch KD. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of cGMP-dependent protein kinase increases the sensitivity of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells to the antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of nitric oxide/cGMP. J Biol Chem 273: 34263–34271, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Collins SP, Uhler MD. Cyclic AMP- and cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases differ in their regulation of cyclic AMP response element-dependent gene transcription. J Biol Chem 274: 8391–8404, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cornwell TL, Pryzwansky KB, Wyatt TA, Lincoln TM. Regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum protein phosphorylation by localized cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol 40: 923–931, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Bie I, Marcinkiewicz M, Malide D, Lazure C, Nakayama K, Bendayan M, Seidah NG. The isoforms of proprotein convertase PC5 are sorted to different subcellular compartments. J Cell Biol 135: 1261–1275, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Decroly E, Wouters S, Di Bello C, Lazure C, Ruysschaert JM, Seidah NG. Identification of the paired basic convertases implicated in HIV gp160 processing based on in vitro assays and expression in CD4(+) cell lines. J Biol Chem 271: 30442–30450, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Drewinko B, Romsdahl MM, Yang LY, Ahearn MJ, Trujillo JM. Establishment of a human carcinoembryonic antigen-producing colon adenocarcinoma cell line. Cancer Res 36: 467–475, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dubois CM, Blanchette F, Laprise MH, Leduc R, Grondin F, Seidah NG. Evidence that furin is an authentic transforming growth factor-beta1-converting enzyme. Am J Pathol 158: 305–316, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Feil R, Gappa N, Rutz M, Schlossmann J, Rose CR, Konnerth A, Brummer S, Kuhbandner S, Hofmann F. Functional reconstitution of vascular smooth muscle cells with cGMP-dependent protein kinase I isoforms. Circ Res 90: 1080–1086, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garg UC, Hassid A. Nitric oxide-generating vasodilators and 8-bromo-cyclic guanosine monophosphate inhibit mitogenesis and proliferation of cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest 83: 1774–1777, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In: Proteomics Protocols Handbook, edited by Walker JM. Clifton, NJ: Humana, 2005, p. 571–607 [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grantham R. Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science 185: 862–864, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gudi T, Casteel DE, Vinson C, Boss GR, Pilz RB. NO activation of fos promoter elements requires nuclear translocation of G-kinase I and CREB phosphorylation but is independent of MAP kinase activation. Oncogene 19: 6324–6333, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gudi T, Huvar I, Meinecke M, Lohmann SM, Boss GR, Pilz RB. Regulation of gene expression by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Transactivation of the c-fos promoter. J Biol Chem 271: 4597–4600, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gudi T, Lohmann SM, Pilz RB. Regulation of gene expression by cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase requires nuclear translocation of the kinase: identification of a nuclear localization signal. Mol Cell Biol 17: 5244–5254, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hatsuzawa K, Nagahama M, Takahashi S, Takada K, Murakami K, Nakayama K. Purification and characterization of furin, a Kex2-like processing endoprotease, produced in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem 267: 16094–16099, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Heil WG, Landgraf W, Hofmann F. A catalytically active fragment of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Occupation of its cGMP-binding sites does not affect its phosphotransferase activity. Eur J Biochem 168: 117–121, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Henrich S, Cameron A, Bourenkov GP, Kiefersauer R, Huber R, Lindberg I, Bode W, Than ME. The crystal structure of the proprotein processing proteinase furin explains its stringent specificity. Nat Struct Biol 10: 520–526, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Henrich S, Lindberg I, Bode W, Than ME. Proprotein convertase models based on the crystal structures of furin and kexin: explanation of their specificity. J Mol Biol 345: 211–227, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Iatan I, Dastani Z, Do R, Weissglas-Volkov D, Ruel I, Lee JC, Huertas-Vazquez A, Taskinen MR, Prat A, Seidah NG, Pajukanta P, Engert JC, Genest J. Genetic variation at the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 5 gene modulates high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2: 467–475, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ihaka R, Gentleman R. R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J Comput Graph Stat 5: 299–314, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jean F, Basak A, Rondeau N, Benjannet S, Hendy GN, Seidah NG, Chretien M, Lazure C. Enzymic characterization of murine and human prohormone convertase-1 (mPC1 and hPC1) expressed in mammalian GH4C1 cells. Biochem J 292: 891–900, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jean F, Stella K, Thomas L, Liu G, Xiang Y, Reason AJ, Thomas G. alpha1-Antitrypsin Portland, a bioengineered serpin highly selective for furin: application as an antipathogenic agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 7293–7298, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Joyce NC, DeCamilli P, Boyles J. Pericytes, like vascular smooth muscle cells, are immunocytochemically positive for cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase. Microvasc Res 28: 206–219, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kang T, Zhao YG, Pei D, Sucic JF, Sang QX. Intracellular activation of human adamalysin 19/disintegrin and metalloproteinase 19 by furin occurs via one of the two consecutive recognition sites. J Biol Chem 277: 25583–25591, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kappert K, Furundzija V, Fritzsche J, Margeta C, Kruger J, Meyborg H, Fleck E, Stawowy P. Integrin cleavage regulates bidirectional signalling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Thromb Haemost 103: 556–563, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim JJ, Casteel DE, Huang G, Kwon TH, Ren RK, Zwart P, Headd JJ, Brown NG, Chow DC, Palzkill T, Kim C. Co-crystal structures of PKG Ibeta (92–227) with cGMP and cAMP reveal the molecular details of cyclic-nucleotide binding. PLos One 6: e18413, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Komada M, Hatsuzawa K, Shibamoto S, Ito F, Nakayama K, Kitamura N. Proteolytic processing of the hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor receptor by furin. FEBS Lett 328: 25–29, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee JE, Patel K, Almodovar S, Tuder RM, Flores SC, Sehgal PB. Dependence of Golgi apparatus integrity on nitric oxide in vascular cells: implications in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1141–H1158, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lehmann M, Rigot V, Seidah NG, Marvaldi J, Lissitzky JC. Lack of integrin alpha-chain endoproteolytic cleavage in furin-deficient human colon adenocarcinoma cells LoVo. Biochem J 317: 803–809, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Li N, Luo W, Juhong Z, Yang J, Wang H, Zhou L, Chang J. Associations between genetic variations in the FURIN gene and hypertension (Abstract). BMC Med Genet 11: 124, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin YJ, Markham NE, Balasubramaniam V, Tang JR, Maxey A, Kinsella JP, Abman SH. Inhaled nitric oxide enhances distal lung growth after exposure to hyperoxia in neonatal rats. Pediatr Res 58: 22–29, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lincoln TM, Dey N, Sellak H. Invited review: cGMP-dependent protein kinase signaling mechanisms in smooth muscle: from the regulation of tone to gene expression. J Appl Physiol 91: 1421–1430, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lincoln TM, Wu X, Sellak H, Dey N, Choi CS. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype by cyclic GMP and cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase. Front Biosci 11: 356–367, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lissitzky JC, Luis J, Munzer JS, Benjannet S, Parat F, Chretien M, Marvaldi J, Seidah NG. Endoproteolytic processing of integrin pro-alpha subunits involves the redundant function of furin and proprotein convertase (PC) 5A, but not paired basic amino acid converting enzyme (PACE) 4, PC5B or PC7. Biochem J 346: 133–138, 2000 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lusson J, Vieau D, Hamelin J, Day R, Chretien M, Seidah NG. cDNA structure of the mouse and rat subtilisin/kexin-like PC5: a candidate proprotein convertase expressed in endocrine and nonendocrine cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 6691–6695, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. MacMillan-Crow LA, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Lincoln TM. Identification and possible localization of cGMP-dependent protein kinase in bovine aortic endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 201: 531–537, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mayer G, Boileau G, Bendayan M. Furin interacts with proMT1-MMP and integrin alphaV at specialized domains of renal cell plasma membrane. J Cell Sci 116: 1763–1773, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McCurnin DC, Pierce RA, Chang LY, Gibson LL, Osborne-Lawrence S, Yoder BA, Kerecman JD, Albertine KH, Winter VT, Coalson JJ, Crapo JD, Grubb PH, Shaul PW. Inhaled NO improves early pulmonary function and modifies lung growth and elastin deposition in a baboon model of neonatal chronic lung disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L450–L459, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McMahon S, Charbonneau M, Grandmont S, Richard DE, Dubois CM. Transforming growth factor beta1 induces hypoxia-inducible factor-1 stabilization through selective inhibition of PHD2 expression. J Biol Chem 281: 24171–24181, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Misumi Y, Oda K, Fujiwara T, Takami N, Tashiro K, Ikehara Y. Functional expression of furin demonstrating its intracellular localization and endoprotease activity for processing of proalbumin and complement pro-C3. J Biol Chem 266: 16954–16959, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Monken CE, Gill GN. Structural analysis of cGMP-dependent protein kinase using limited proteolysis. J Biol Chem 255: 7067–7070, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nakagawa T, Murakami K, Nakayama K. Identification of an isoform with an extremely large Cys-rich region of PC6, a Kex2-like processing endoprotease. FEBS Lett 327: 165–171, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nicklin S, Baker A. Simple methods for preparing recombinant adenovirus for high-efficiency transduction of vascular cells. In: Methods in Molecular Medicine, Vascular Disease, edited by Baker A. Totowa, NJ: Humana; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. O'Carroll SJ, Hall AR, Myers CJ, Braithwaite AW, Dix BR. Quantifying adenoviral titers by spectrophotometry. Biotechniques 28: 408–412, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Peiretti F, Canault M, Deprez-Beauclair P, Berthet V, Bonardo B, Juhan-Vague I, Nalbone G. Intracellular maturation and transport of tumor necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme. Exp Cell Res 285: 278–285, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pilz RB, Broderick KE. Role of cyclic GMP in gene regulation. Front Biosci 10: 1239–1268, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Plaimauer B, Mohr G, Wernhart W, Himmelspach M, Dorner F, Schlokat U. ‘Shed’ furin: mapping of the cleavage determinants and identification of its C-terminus. Biochem J 354: 689–695, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pryzwansky KB, Kidao S, Wyatt TA, Reed W, Lincoln TM. Localization of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase in human mononuclear phagocytes. J Leukoc Biol 57: 670–678, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rasband WS. ImageJ. Bethesda, MD: 1997–2007 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A. MEROPS: the database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucleic Acids Res 40: D343–D350, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Richie-Jannetta R, Francis SH, Corbin JD. Dimerization of cGMP-dependent protein kinase Ibeta is mediated by an extensive amino-terminal leucine zipper motif, and dimerization modulates enzyme function. J Biol Chem 278: 50070–50079, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Roberts JD, Jr, Chiche JD, Weimann J, Steudel W, Zapol WM, Bloch KD. Nitric oxide inhalation decreases pulmonary artery remodeling in the injured lungs of rat pups. Circ Res 87: 140–145, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Roberts JD, Jr, Roberts CT, Jones RC, Zapol WM, Bloch KD. Continuous nitric oxide inhalation reduces pulmonary arterial structural changes, right ventricular hypertrophy, and growth retardation in the hypoxic newborn rat. Circ Res 76: 215–222, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rousselet E, Benjannet S, Hamelin J, Canuel M, Seidah NG. The Proprotein Convertase PC7: unique zymogen activation and trafficking pathways. J Biol Chem 286: 2728–2738, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ruth P, Pfeifer A, Kamm S, Klatt P, Dostmann WR, Hofmann F. Identification of the amino acid sequences responsible for high affinity activation of cGMP kinase Ialpha. J Biol Chem 272: 10522–10528, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sauzeau V, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Marionneau C, Loirand G, Pacaud P. RhoA expression is controlled by nitric oxide through cGMP-dependent protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem 278: 9472–9480, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sehgal PB, Mukhopadhyay S, Xu F, Patel K, Shah M. Dysfunction of Golgi tethers, SNAREs, and SNAPs in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L1526–L1542, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Seidah NG, Chretien M. Proprotein and prohormone convertases: a family of subtilases generating diverse bioactive polypeptides. Brain Res 848: 45–62, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Seidah NG, Chretien M, Day R. The family of subtilisin/kexin like pro-protein and pro-hormone convertases: Divergent or shared function. Biochimie 76: 197–209, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Seidah NG, Mayer G, Zaid A, Rousselet E, Nassoury N, Poirier S, Essalmani R, Prat A. The activation and physiological functions of the proprotein convertases. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40: 1111–1125, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Siegfried G, Basak A, Cromlish JA, Benjannet S, Marcinkiewicz J, Chretien M, Seidah NG, Khatib AM. The secretory proprotein convertases furin, PC5, and PC7 activate VEGF-C to induce tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest 111: 1723–1732, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Siegfried G, Basak A, Prichett-Pejic W, Scamuffa N, Ma L, Benjannet S, Veinot JP, Calvo F, Seidah N, Khatib AM. Regulation of the stepwise proteolytic cleavage and secretion of PDGF-B by the proprotein convertases. Oncogene 24: 6925–6935, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Stawowy P, Kallisch H, Borges Pereira Stawowy N, Stibenz D, Veinot JP, Grafe M, Seidah NG, Chretien M, Fleck E, Graf K. Immunohistochemical localization of subtilisin/kexin-like proprotein convertases in human atherosclerosis. Virchows Arch 446: 351–359, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Stawowy P, Kallisch H, Kilimnik A, Margeta C, Seidah NG, Chretien M, Fleck E, Graf K. Proprotein convertases regulate insulin-like growth factor 1-induced membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase in VSMCs via endoproteolytic activation of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 321: 531–538, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Stawowy P, Marcinkiewicz J, Graf K, Seidah N, Chretien M, Fleck E, Marcinkiewicz M. Selective expression of the proprotein convertases furin, pc5, and pc7 in proliferating vascular smooth muscle cells of the rat aorta in vitro. J Histochem Cytochem 49: 323–332, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, Derge JG, Klausner RD, Collins FS, Wagner L, Shenmen CM, Schuler GD, Altschul SF, Zeeberg B, Buetow KH, Schaefer CF, Bhat NK, Hopkins RF, Jordan H, Moore T, Max SI, Wang J, Hsieh F, Diatchenko L, Marusina K, Farmer AA, Rubin GM, Hong L, Stapleton M, Soares MB, Bonaldo MF, Casavant TL, Scheetz TE, Brownstein MJ, Usdin TB, Toshiyuki S, Carninci P, Prange C, Raha SS, Loquellano NA, Peters GJ, Abramson RD, Mullahy SJ, Bosak SA, McEwan PJ, McKernan KJ, Malek JA, Gunaratne PH, Richards S, Worley KC, Hale S, Garcia AM, Gay LJ, Hulyk SW, Villalon DK, Muzny DM, Sodergren EJ, Lu X, Gibbs RA, Fahey J, Helton E, Ketteman M, Madan A, Rodrigues S, Sanchez A, Whiting M, Young AC, Shevchenko Y, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW, Touchman JW, Green ED, Dickson MC, Rodriguez AC, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Myers RM, Butterfield YS, Krzywinski MI, Skalska U, Smailus DE, Schnerch A, Schein JE, Jones SJ, Marra MA. Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 16899–16903, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Sugiura T, Nakanishi H, Roberts JD., Jr Proteolytic processing of cGMP-dependent protein kinase I mediates nuclear cGMP signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 103: 53–60, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Takahashi S, Kasai K, Hatsuzawa K, Kitamura N, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y, Murakami K, Nakayama K. A mutation of furin causes the lack of precursor-processing activity in human colon carcinoma LoVo cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 195: 1019–1026, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Takahashi S, Nakagawa T, Kasai K, Banno T, Duguay SJ, Van de Ven WJ, Murakami K, Nakayama K. A second mutant allele of furin in the processing-incompetent cell line, LoVo. Evidence for involvement of the homo B domain in autocatalytic activation. J Biol Chem 270: 26565–26569, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Takio K, Smith SB, Walsh KA, Krebs EG, Titani K. Amino acid sequence around a hinge region and its autophosphorylation site in bovine Lung cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 258: 5531–5536, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Takio K, Wade RD, Smith SB, Krebs EG, Walsh KA, Titani K. Guanosine cyclic 3′,5′-phosphate dependent protein kinase, a chimeric protein homologous with two separate protein families. Biochemistry 23: 4207–4218, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Thomas G. Furin at the cutting edge: from protein traffic to embryogenesis and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 753–766, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Van de Ven WJ, Creemers JW, Roebroek AJ. Furin: the prototype mammalian subtilisin-like proprotein-processing enzyme. Endoproteolytic cleavage at paired basic residues of proproteins of the eukaryotic secretory pathway. Enzyme 45: 257–270, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Vidricaire G, Denault JB, Leduc R. Characterization of a secreted form of human furin endoprotease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 195: 1011–1018, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wang Y, El-Zaru MR, Surks HK, Mendelsohn ME. Formin homology domain protein (FHOD1) is a cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase I-binding protein and substrate in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 279: 24420–24426, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Wolfsgruber W, Feil S, Brummer S, Kuppinger O, Hofmann F, Feil R. A proatherogenic role for cGMP-dependent protein kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 13519–13524, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yamashita J, Itoh H, Ogawa Y, Tamura N, Takaya K, Igaki T, Doi K, Chun TH, Inoue M, Masatsugu K, Nakao K. Opposite regulation of Gax homeobox expression by angiotensin II and C-type natriuretic peptide. Hypertension 29: 381–387, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yana I, Weiss SJ. Regulation of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase activation by proprotein convertases. Mol Biol Cell 11: 2387–2401, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Yi B, Cui J, Ning JN, Wang GS, Qian GS, Lu KZ. Over-expression of PKGIalpha inhibits hypoxia-induced proliferation, Akt activation, and phenotype modulation of human PASMCs: the role of phenotype modulation of PASMCs in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Gene 492: 354–360, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Zhang T, Zhuang S, Casteel DE, Looney DJ, Boss GR, Pilz RB. A cysteine-rich LIM-only protein mediates regulation of smooth muscle-specific gene expression by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 282: 33367–33380, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhou W, Dasgupta C, Negash S, Raj JU. Modulation of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype in hypoxia: role of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L1459–L1466, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]