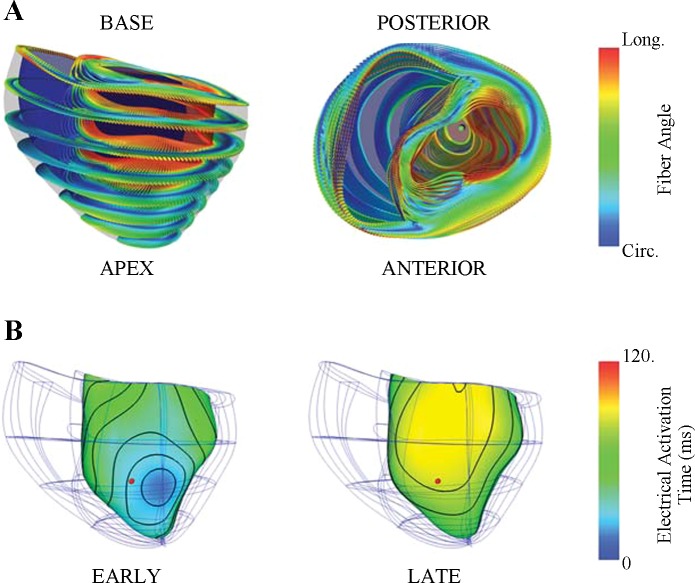

Fig. 2.

Dog-specific computational model of the failing canine heart. A: 128 tricubic Hermite finite elements were used to describe realistic geometry obtained from one experimental animal (dog 6). Anterior (left) and basal (right) views of the fiber architecture fitted to DT-MRI measurements were registered to the mesh using a log-Euclidean framework to interpolate the tensors (23). The 3-dimensional local fiber-sheet structure is visualized by the shape, orientation, and color glyphs; the primary and minor axes of the glyphs represent the fiber and sheet-normal axes, respectively. The glyph color redundantly encodes circumferential to longitudinal (blue to red) fiber orientation to illustrate the smooth fiber variation. B: ventricular pacing at 2 separate locations resulted in opposite sequences of electrical activation. Local activation times are rendered in color at the subendocardial surface of the finite-element model. During left ventricular anterior apical pacing (EARLY, left), subendocardial activation was relatively uniform across the anterolateral apical wall and occurred earlier compared with the septal and right ventricular free walls. Pacing on the posterior basal left ventricle (LATE, right) resulted in delayed activation at the anterolateral left ventricle. A comparable anterolateral location (red dot) to the experimental protocol was used to compare differences between early at late activation. Local electrical activation time at the mechanical site was 28 and 81 ms for EARLY and LATE, respectively. Circ, circumferential; Long, longitudinal.