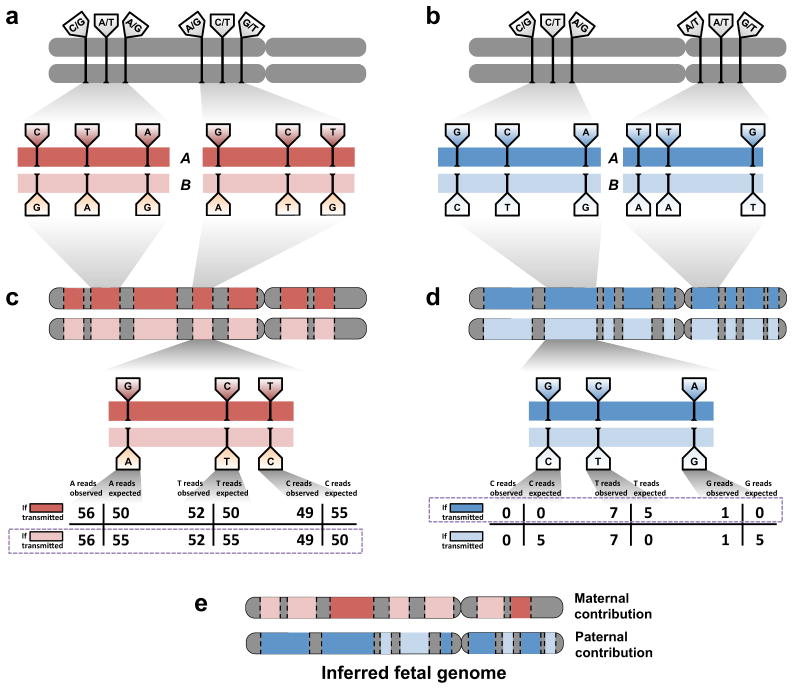

Figure 3.

Inference of the fetal genome from haplotype blocks. (a). Phasing of maternal heterozygous sites into haplotype blocks (red bars). Haplotype blocks contain dozens or hundreds of such sites and cover over 300 kilobases on average. A single chromosome may have over 100 haplotype blocks; contiguity between blocks is not defined. Approximately 90% of all heterozygous sites are incorporated into haplotype blocks. Sites shown do not represent real data. (b). Phasing of paternal heterozygous sites into haplotype blocks (blue bars). Paternal and maternal blocks may overlap but are independently defined. (c). Schematic of inference of fetal inheritance of maternal haplotype blocks. Numbers shown assume a constant sequencing depth of 100X at each. After sequencing the cfDNA, evidence of deviations from expected allele counts is aggregated over each site in haplotype blocks “A” and “B”, and the more likely block is predicted. Block-level predictions in turn determine predictions at each contained site. The site in the center of the block would be incorrectly predicted if sites were considered independently; its inclusion in a haplotype block mitigates sampling noise and corrects the prediction. (d). Schematic of inference of fetal inheritance of paternal haplotype blocks. Numbers are presented as in (c). The observed “G” allele at the rightmost site, likely to cause an incorrect prediction if sites were considered independently, is now correctly identified as an error introduced during the sequencing process rather than evidence of transmission of the “G” allele. (e). The inferred fetal genome is a composite of the parental haplotype blocks.