Abstract

In this systematic review, we sought to evaluate the effect of physical activity or nutrition interventions (or both) in adults with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (nsclc).

Methods

A systematic search for relevant clinical trials was conducted in 6 electronic databases, by hand searching, and by contacting key investigators. No limits were placed on study language. Information about recruitment rates, protocol adherence, patient-reported and clinical outcome measures, and study conclusions was extracted. Methodologic quality and risk of bias in each study was assessed using validated tools.

Main Results

Six papers detailing five studies involving 203 participants met the inclusion criteria. Two of the studies were single-cohort physical activity studies (54 participants), and three were controlled nutrition studies (149 participants). All were conducted in an outpatient setting. None of the included studies combined physical activity with nutrition interventions.

Conclusions

Our systematic review suggests that exercise and nutrition interventions are not harmful and may have beneficial effects on unintentional weight loss, physical strength, and functional performance in patients with advanced nsclc. However, the observed improvements must be interpreted with caution, because findings were not consistent across the included studies. Moreover, the included studies were small and at significant risk of bias.

More research is required to ascertain the optimal physical activity and nutrition interventions in advanced inoperable nsclc. Specifically, the potential benefits of combining physical activity with nutrition counselling have yet to be adequately explored in this population.

Keywords: Palliation, rehabilitation, systematic review, lungs, exercise, nutrition

1. BACKGROUND

Pain, fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss are some of the most prevalent physical symptoms in advanced cancers1,2. Unintentional weight loss is recognized as an independent predictor of poor health and earlier death in advanced cancer3,4. Nutrition status has also been found to directly affect both tolerance to and effectiveness of palliative chemotherapy treatments for solid tumours3. Although pain control in cancer is continually improving, with standardized guidance for assessment and treatment5, the optimal management of fatigue, anorexia, and weight loss—all recognized components of cancer cachexia syndrome—are still to be determined6,7. Cancer cachexia syndrome is multifactorial and complex, and its causes are still not fully understood. A group of leading international experts in clinical cancer cachexia research and treatment recently defined it thus6:

[A] multifactorial syndrome defined by an ongoing loss of skeletal muscle mass (with or without loss of fat mass) that cannot be fully reversed by conventional nutritional support and leads to progressive functional impairment. Its pathophysiology is characterised by a negative protein and energy balance driven by a variable combination of reduced food intake and abnormal metabolism.

(p. 490)

Lung cancer accounts for the highest proportion of cancer deaths in the developed world, with non-small-cell lung cancer (nsclc) accounting for approximately 70%–85% of all lung cancer diagnoses8–10. The high incidence of cancer cachexia symptoms arising in advanced nsclc11 has made this patient population a frequent target for cancer cachexia research12,13. Specialized multidisciplinary clinics combining individualized nutrition and physical activity interventions, together with optimal psychosocial support and medical management, are being developed worldwide. Within these clinics, dietetic support includes advice on appropriate food selection based on likes, dislikes, and symptoms affecting dietary intake. Dietitians also advise on food fortification with or without macro- and micronutrient supplementation to correct any dietary deficiencies. Physiotherapists provide individualized exercise plans combining resistance and aerobic training for cardiovascular fitness, muscular strength, muscular endurance, flexibility, and lean mass retention. These clinics appear promising in terms of improved physical functioning, better dietary intake, weight stabilization, and fatigue reduction14–17. Optimal program design and timing of interventions has yet to be determined6,18.

Our aim was to review trials of interventions in physical activity or nutrition (or both) focusing on the management of any combination of fatigue, anorexia, and unintentional weight loss (symptoms of cancer cachexia) in patients with advanced nsclc. A further aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions.

2. METHODS

2.1. Types of Studies

Any type of clinical trial evaluating the effects of physical activity or nutrition interventions for the management of cancer cachexia symptoms in advanced nsclc was eligible for inclusion in the review.

2.2. Types of Participants

Participants in the trials had to be adults (≥18 years of age) with stage iiib or iv nsclc. Participants were included regardless of whether they were actively receiving anticancer therapy at the time of the intervention.

2.3. Types of Interventions

All included papers were required to have a physical activity or nutrition treatment as the main intervention or to contain independently extractable data on such an intervention.

Physical activity interventions were defined as any one or a combination of flexibility training, resistance training, and cardiovascular training. Interventions could be supervised or unsupervised, be undertaken at any location, and be individualized or group-based in nature. Characteristics of the training program such as the type, intensity, frequency, duration, and extent of supervision and adherence are reported if that information was supplied.

Nutrition interventions included any one or a combination of the provision of dietary counselling, prescribed nutritional supplementation, and use of over-the-counter dietary supplements. Characteristics of the nutrition intervention such as the type, dose, duration, and extent of supervision and adherence are reported if that information was supplied.

2.4. Identification of Studies

A search strategy (Appendix A) was designed for identifying studies from the following databases, with no limits imposed on study language: central (Ovid), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Ovid), medline (Ovid), embase (Ovid), cinahl Plus, and the National Research Trials Register up to October 22, 2012. Hand-searches of relevant journals were also undertaken, and the reference lists of all included studies or relevant systematic reviews were checked for further studies. Investigators known to be carrying out research in this area were also contacted for unpublished data or knowledge of the grey literature.

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis

Titles of interest were reviewed by abstract. Potentially significant papers were then obtained in full. Where the relevance of a study was unclear, a consensus was reached by the authors regarding the applicability of the participant group and reported outcome measures. Data were extracted using a pre-designed extraction form. The outcome measures of interest included patient-reported outcomes (provided using validated self-assessment tools) and clinical outcome measures. Information was also extracted on recruitment rates, attrition, adherence to the study protocol, adverse events, survival rates, and key conclusions from each study.

2.6. Assessment of Methodologic Quality of Included Reviews

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias for randomized controlled trials19 and the Critical Appraisal Skills Program: Cohort Studies methodology checklist for single-cohort studies20. Both of those tools consider potential biases in recruitment, measurement, and reporting of study outcomes.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study and Patient Characteristics

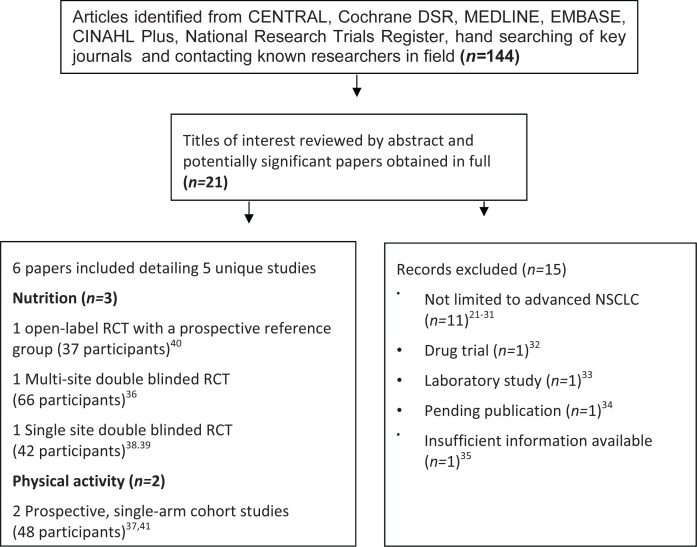

Using the electronic database search strategy, we identified one hundred forty-four potential papers. The electronic database searches identified nine abstracts of interest, and a further twelve were identified by the hand searches or by contacting investigators in the field. After retrieval of twenty-one full-text articles, fifteen studies were excluded21–35 as detailed in Figure 1. The present systematic review includes six papers detailing five studies with a total of 203 participants. The included publications relate to two single-cohort physical activity studies (54 participants) and three controlled nutrition studies (149 participants) undertaken with outpatient populations. No included study combined physical activity and nutrition interventions. Table i describes the characteristics of the included studies.

FIGURE 1.

Search strategy.

TABLE I.

Characteristics of included studies

| Reference | Study details | ||

|---|---|---|---|

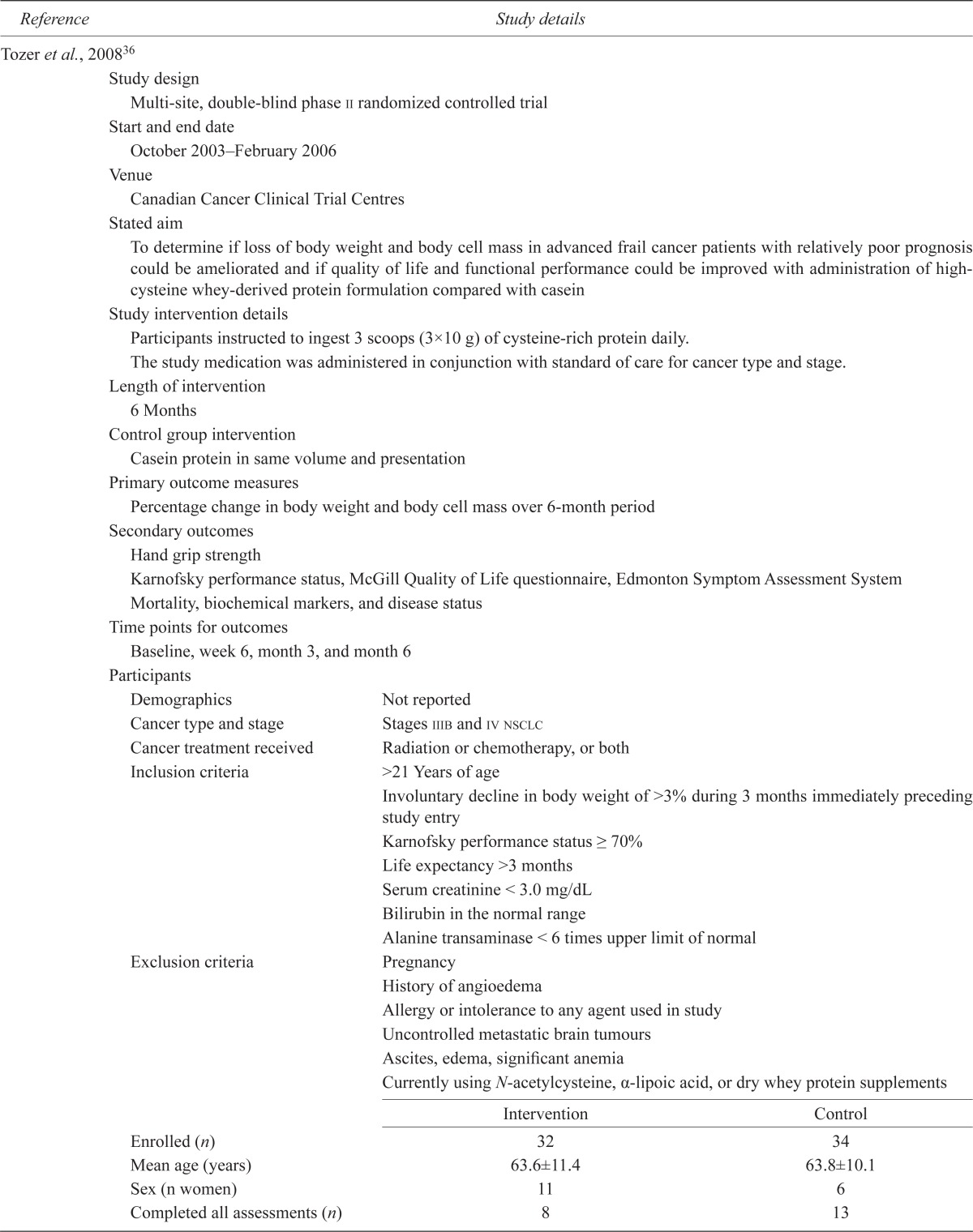

| Tozer et al., 200836 | |||

| Study design | |||

| Multi-site, double-blind phase ii randomized controlled trial | |||

| Start and end date | |||

| October 2003–February 2006 | |||

| Venue | |||

| Canadian Cancer Clinical Trial Centres | |||

| Stated aim | |||

| To determine if loss of body weight and body cell mass in advanced frail cancer patients with relatively poor prognosis could be ameliorated and if quality of life and functional performance could be improved with administration of high-cysteine whey-derived protein formulation compared with casein | |||

| Study intervention details | |||

| Participants instructed to ingest 3 scoops (3×10 g) of cysteine-rich protein daily. | |||

| The study medication was administered in conjunction with standard of care for cancer type and stage. | |||

| Length of intervention | |||

| 6 Months | |||

| Control group intervention | |||

| Casein protein in same volume and presentation | |||

| Primary outcome measures | |||

| Percentage change in body weight and body cell mass over 6-month period | |||

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Hand grip strength | |||

| Karnofsky performance status, McGill Quality of Life questionnaire, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System | |||

| Mortality, biochemical markers, and disease status | |||

| Time points for outcomes | |||

| Baseline, week 6, month 3, and month 6 | |||

| Participants | |||

| Demographics | Not reported | ||

| Cancer type and stage | Stages iiib and iv nsclc | ||

| Cancer treatment received | Radiation or chemotherapy, or both | ||

| Inclusion criteria | >21 Years of age | ||

| Involuntary decline in body weight of >3% during 3 months immediately preceding study entry | |||

| Karnofsky performance status ≥ 70% | |||

| Life expectancy >3 months | |||

| Serum creatinine < 3.0 mg/dL | |||

| Bilirubin in the normal range | |||

| Alanine transaminase < 6 times upper limit of normal | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Pregnancy | ||

| History of angioedema | |||

| Allergy or intolerance to any agent used in study | |||

| Uncontrolled metastatic brain tumours | |||

| Ascites, edema, significant anemia | |||

| Currently using N-acetylcysteine, α-lipoic acid, or dry whey protein supplements | |||

|

|

|||

| Intervention | Control | ||

|

|

|||

| Enrolled (n) | 32 | 34 | |

| Mean age (years) | 63.6±11.4 | 63.8±10.1 | |

| Sex (n women) | 11 | 6 | |

| Completed all assessments (n) | 8 | 13 | |

| Reasons for exclusions or withdrawals | Before week 6, 17 died and 14 withdrew | ||

| Further 8 died and 6 withdrew by 6 months | |||

| Results | |||

| Primary outcomes | Significant increase in body cell mass compared with control | ||

| Secondary outcome | Significant increase in handgrip strength compared with control group | ||

| Conclusions | |||

| Key conclusions of study authors | Survival not reduced by supplementation with cysteine-rich protein compared with casein-based formula | ||

| Intervention reversed cancer-related weight loss and loss of body cell mass significantly, with improvement in muscle force and some quality-of-life parameters, if measurements taken shortly before death were excluded | |||

| Improvements were not replicated within control group | |||

| Other comments | Evidence limited by small number of evaluable patients | ||

| Need to ensure that patients are not in terminal phase of illness before recruiting to this type of intervention | |||

| 22 Patients with colorectal cancer were also recruited to the study, but were not analyzed in this paper | |||

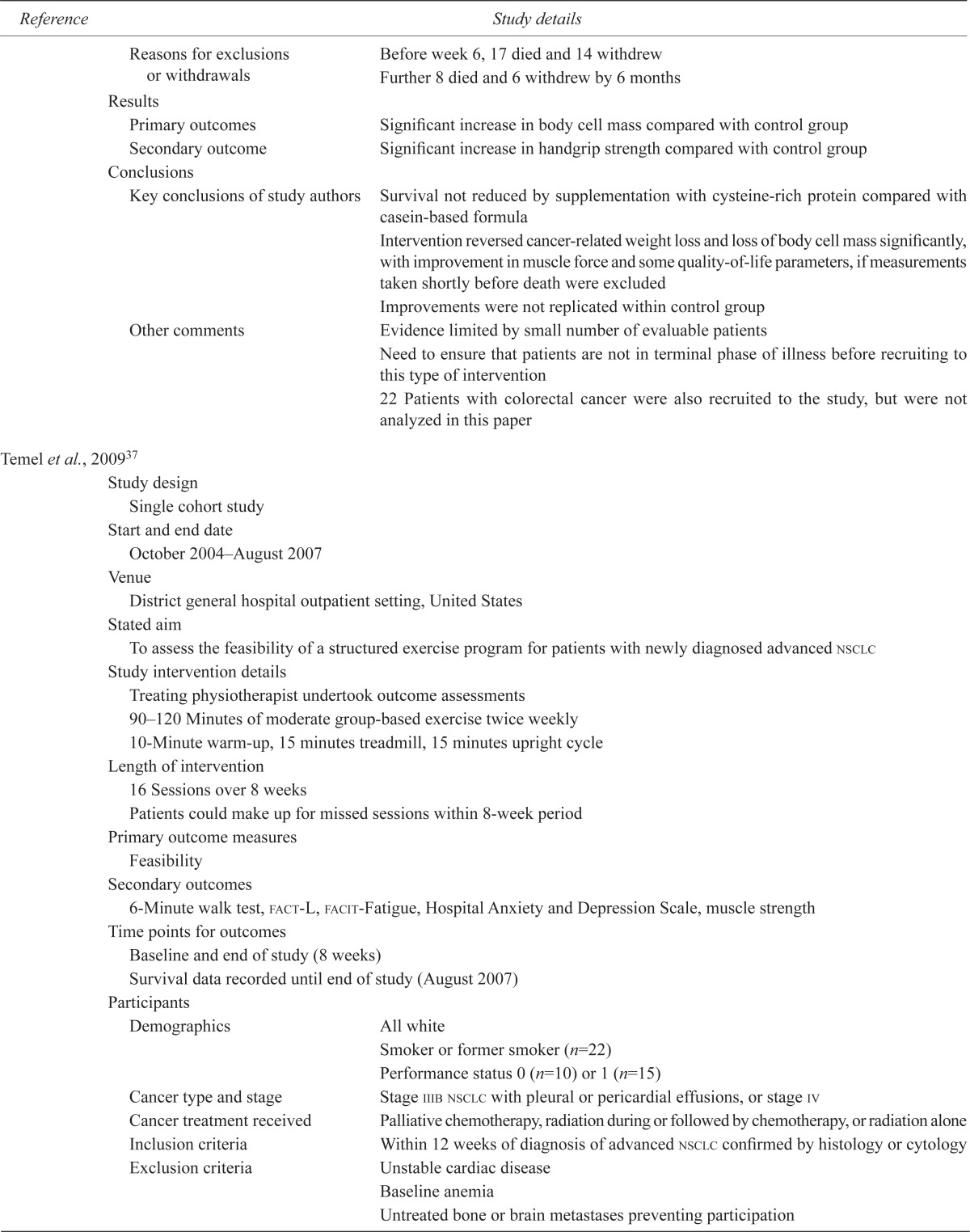

| Temel et al., 200937 | |||

| Study design | |||

| Single cohort study | |||

| Start and end date | |||

| October 2004–August 2007 | |||

| Venue | |||

| District general hospital outpatient setting, United States | |||

| Stated aim | |||

| To assess the feasibility of a structured exercise program for patients with newly diagnosed advanced nsclc | |||

| Study intervention details | |||

| Treating physiotherapist undertook outcome assessments | |||

| 90–120 Minutes of moderate group-based exercise twice weekly | |||

| 10-Minute warm-up, 15 minutes treadmill, 15 minutes upright cycle | |||

| Length of intervention | |||

| 16 Sessions over 8 weeks | |||

| Patients could make up for missed sessions within 8-week period | |||

| Primary outcome measures | |||

| Feasibility | |||

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| 6-Minute walk test, fact-L, facit-Fatigue, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, muscle strength | |||

| Time points for outcomes | |||

| Baseline and end of study (8 weeks) | |||

| Survival data recorded until end of study (August 2007) | |||

| Participants | |||

| Demographics | All white | ||

| Smoker or former smoker (n=22) | |||

| Performance status 0 (n=10) or 1 (n=15) | |||

| Cancer type and stage | Stage iiib nsclc with pleural or pericardial effusions, or stage iv | ||

| Cancer treatment received | Palliative chemotherapy, radiation during or followed by chemotherapy, or radiation alone | ||

| Inclusion criteria | Within 12 weeks of diagnosis of advanced nsclc confirmed by histology or cytology | ||

| Exclusion criteria | Unstable cardiac disease | ||

| Baseline anemia | |||

| Untreated bone or brain metastases preventing participation | |||

| Enrolled (n) | 25 | ||

| Mean age [(range) years] | 68 (48–81) | ||

| Sex (n women) | 16 | ||

| Completed all assessments (n) | 11 | ||

| Reasons for exclusions or withdrawals | Withdrawals because of health deterioration before (n=5) or during study (n=6), travel (n=1), unspecified (n=1) | ||

| Results | |||

| Primary outcomes | 76% Completed or participated in program as long as physically able with no negative impact on fatigue or quality of life | ||

| Secondary outcome | Statistically significant improvements in the lung cancer subscale of fact-L and in elbow extension | ||

| No other significant findings | |||

| Conclusions | |||

| Key conclusions of study authors | A structured, supervised exercise program may improve symptom burden and functional capacity in patients with advanced nsclc. | ||

| Unable to meet target recruitment rate of 30 particiants. | |||

| Recommend increasing the accessibility of similar programs by reviewing location, duration, and intensity of physical activity | |||

| Other comments | No consideration of long-term intervention outcomes other than survival and high attrition rate | ||

| van der Meij et al., 201038 and 201239 | |||

| Study design | |||

| Double-blind randomized controlled study | |||

| Start and end date | |||

| March 15, 2005, to January 31, 2008 | |||

| Venue | |||

| Amsterdam, Netherlands | |||

| Stated aim | |||

| To investigate the effects of an oral nutrition supplement containing omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on nutrition status and inflammatory markers in patients with stage iii nsclc undergoing multimodality therapy | |||

| Study intervention details | |||

| Consume 2 cans daily of either a protein- and energy-dense oral nutrition supplement [480 mL ProSure (Abbott Nutrition, Maidenhead, U.K.) containing omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids providing 2.02 g epa plus 0.92 g dha daily | |||

| Intake recorded in compliance diary | |||

| Length of intervention | |||

| 5 Weeks alongside chemoradiotherapy treatment | |||

| Control group intervention | |||

| Isocaloric control oral nutritional supplement without added PUFA | |||

| Primary outcome measures | |||

| Body weight, body mass index, mid-arm muscle circumference, fat-free mass (bioelectrical impedance) | |||

| Inflammatory markers | |||

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Diary and plasma phospholipid concentration readings | |||

| eortc qlq-C30 | |||

| Handgrip strength, physical activity (accelerometer) | |||

| Adverse events | |||

| Time points for outcomes | |||

| Baseline, 3 weeks and 5 weeks | |||

| Participants | |||

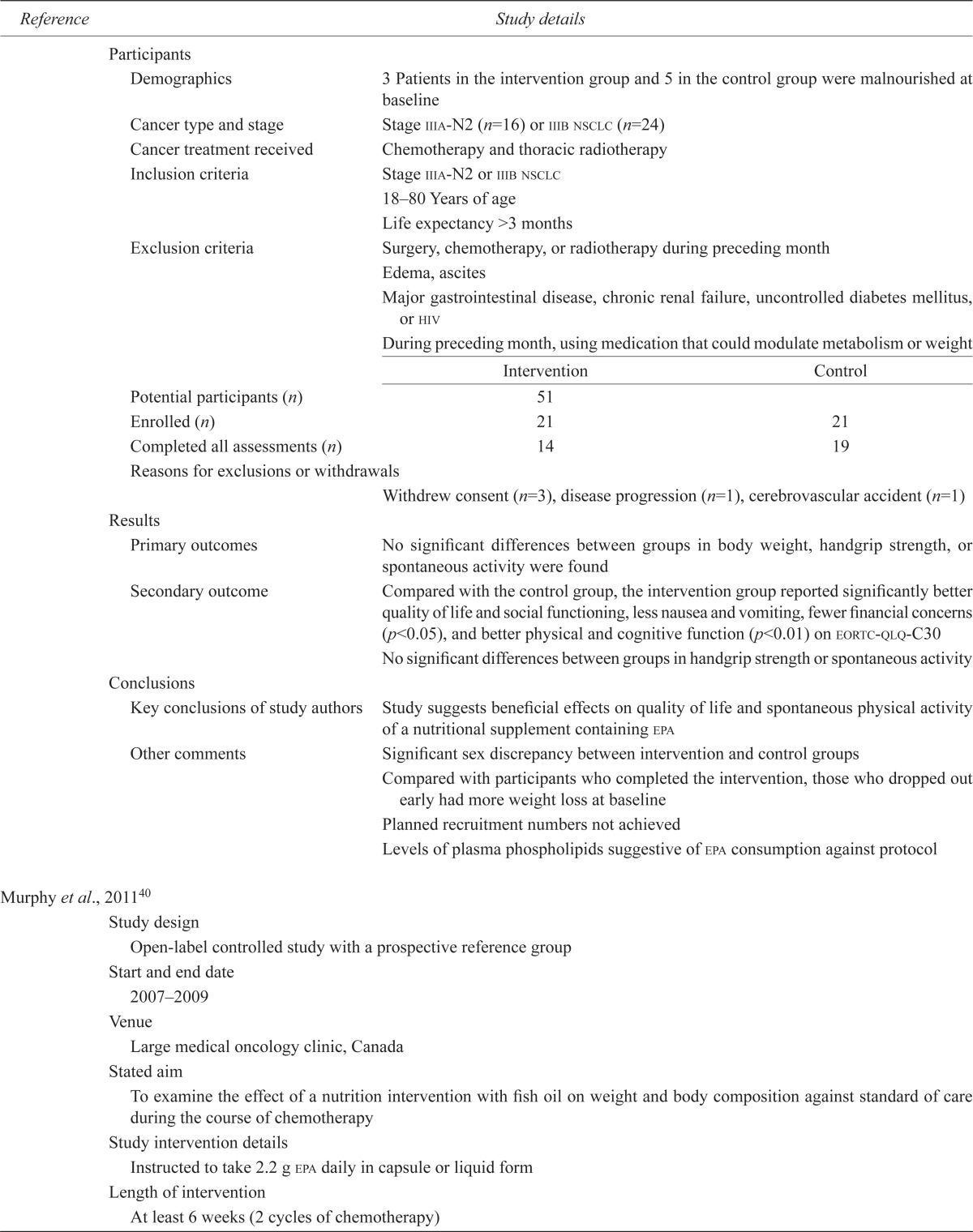

| Demographics | 3 Patients in the intervention group and 5 in the control group were malnourished at baseline | ||

| Cancer type and stage | Stage iiia-N2 (n=16) or iiib nsclc (n=24) | ||

| Cancer treatment received | Chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy | ||

| Inclusion criteria | Stage iiia-N2 or iiib nsclc | ||

| 18–80 Years of age | |||

| Life expectancy >3 months | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy during preceding month | ||

| Edema, ascites | |||

| Major gastrointestinal disease, chronic renal failure, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, or hiv | |||

| During preceding month, using medication that could modulate metabolism or weight | |||

|

|

|||

| Intervention | Control | ||

|

|

|||

| Potential participants (n) | 51 | ||

| Enrolled (n) | 21 | 21 | |

| Completed all assessments (n) | 14 | 19 | |

| Reasons for exclusions or withdrawals | |||

| Withdrew consent (n=3), disease progression (n=1), cerebrovascular accident (n=1) | |||

| Results | |||

| Primary outcomes | No significant differences between groups in body weight, handgrip strength, or spontaneous activity were found | ||

| Secondary outcome | Compared with the control group, the intervention group reported significantly better quality of life and social functioning, less nausea and vomiting, fewer financial concerns (p<0.05), and better physical and cognitive function (p<0.01) on eortc-qlq-C30 | ||

| No significant differences between groups in handgrip strength or spontaneous activity | |||

| Conclusions | |||

| Key conclusions of study authors | Study suggests beneficial effects on quality of life and spontaneous physical activity of a nutritional supplement containing epa | ||

| Other comments | Significant sex discrepancy between intervention and control groups | ||

| Compared with participants who completed the intervention, those who dropped out early had more weight loss at baseline | |||

| Planned recruitment numbers not achieved | |||

| Levels of plasma phospholipids suggestive of epa consumption against protocol | |||

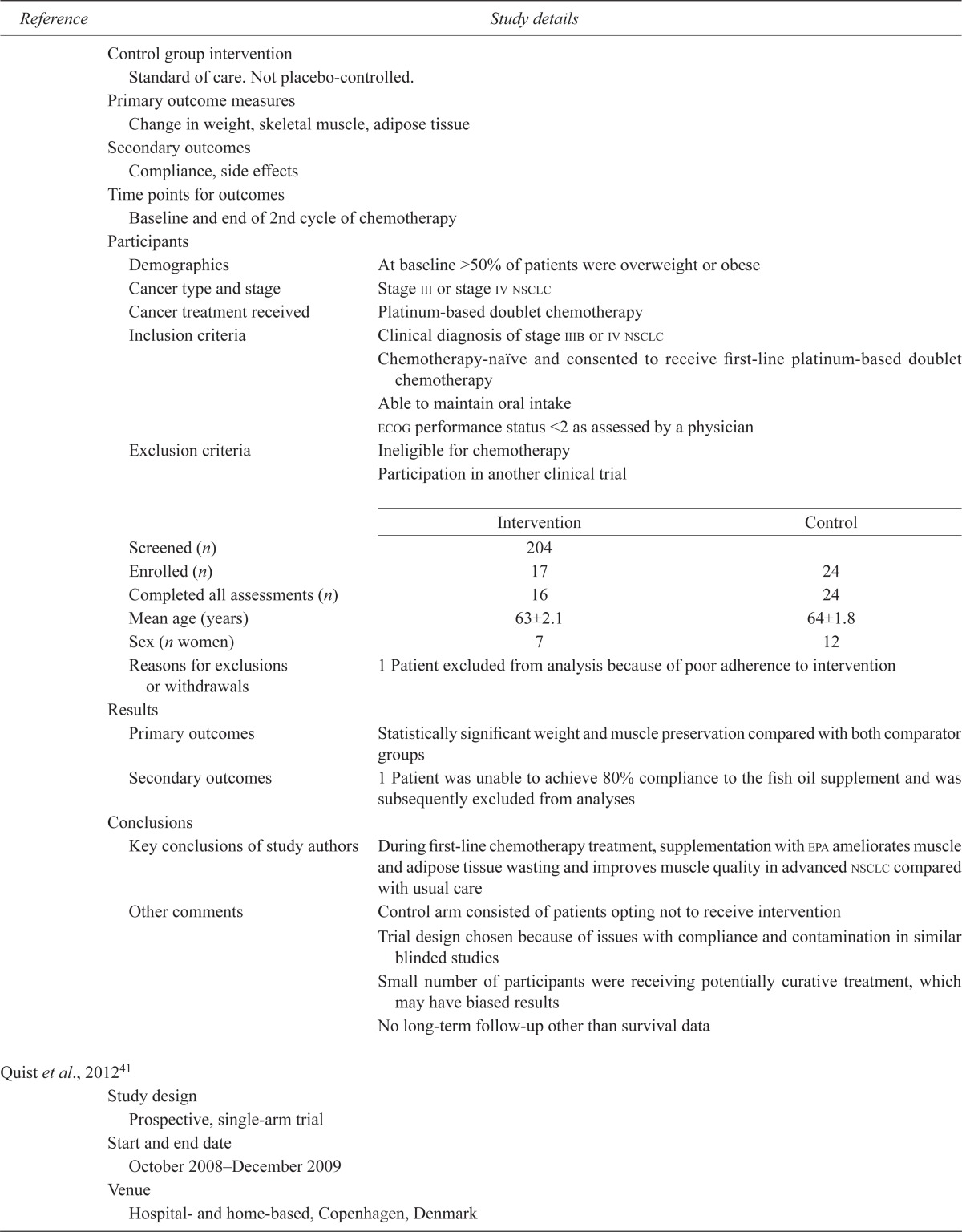

| Murphy et al., 201140 | |||

| Study design | |||

| Open-label controlled study with a prospective reference group | |||

| Start and end date | |||

| 2007–2009 | |||

| Venue | |||

| Large medical oncology clinic, Canada | |||

| Stated aim | |||

| To examine the effect of a nutrition intervention with fish oil on weight and body composition against standard of care during the course of chemotherapy | |||

| Study intervention details | |||

| Instructed to take 2.2 g epa daily in capsule or liquid form | |||

| Length of intervention | |||

| At least 6 weeks (2 cycles of chemotherapy) | |||

| Control group intervention | |||

| Standard of care. Not placebo-controlled. | |||

| Primary outcome measures | |||

| Change in weight, skeletal muscle, adipose tissue | |||

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Compliance, side effects | |||

| Time points for outcomes | |||

| Baseline and end of 2nd cycle of chemotherapy | |||

| Participants | |||

| Demographics | At baseline >50% of patients were overweight or obese | ||

| Cancer type and stage | Stage iii or stage iv nsclc | ||

| Cancer treatment received | Platinum-based doublet chemotherapy | ||

| Inclusion criteria | Clinical diagnosis of stage iiib or iv nsclc | ||

| Chemotherapy-naïve and consented to receive first-line platinum-based doublet chemotherapy | |||

| Able to maintain oral intake | |||

| ecog performance status <2 as assessed by a physician | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Ineligible for chemotherapy | ||

| Participation in another clinical trial | |||

|

|

|||

| Intervention | Control | ||

|

|

|||

| Screened (n) | 204 | ||

| Enrolled (n) | 17 | 24 | |

| Completed all assessments (n) | 16 | 24 | |

| Mean age (years) | 63±2.1 | 64±1.8 | |

| Sex (n women) | 7 | 12 | |

| Reasons for exclusions or withdrawals | 1 Patient excluded from analysis because of poor adherence to intervention | ||

| Results | |||

| Primary outcomes | Statistically significant weight and muscle preservation compared with both comparator groups | ||

| Secondary outcomes | 1 Patient was unable to achieve 80% compliance to the fish oil supplement and was subsequently excluded from analyses | ||

| Conclusions | |||

| Key conclusions of study authors | During first-line chemotherapy treatment, supplementation with epa ameliorates muscle and adipose tissue wasting and improves muscle quality in advanced nsclc compared with usual care | ||

| Other comments | Control arm consisted of patients opting not to receive intervention | ||

| Trial design chosen because of issues with compliance and contamination in similar blinded studies | |||

| Small number of participants were receiving potentially curative treatment, which may have biased results | |||

| No long-term follow-up other than survival data | |||

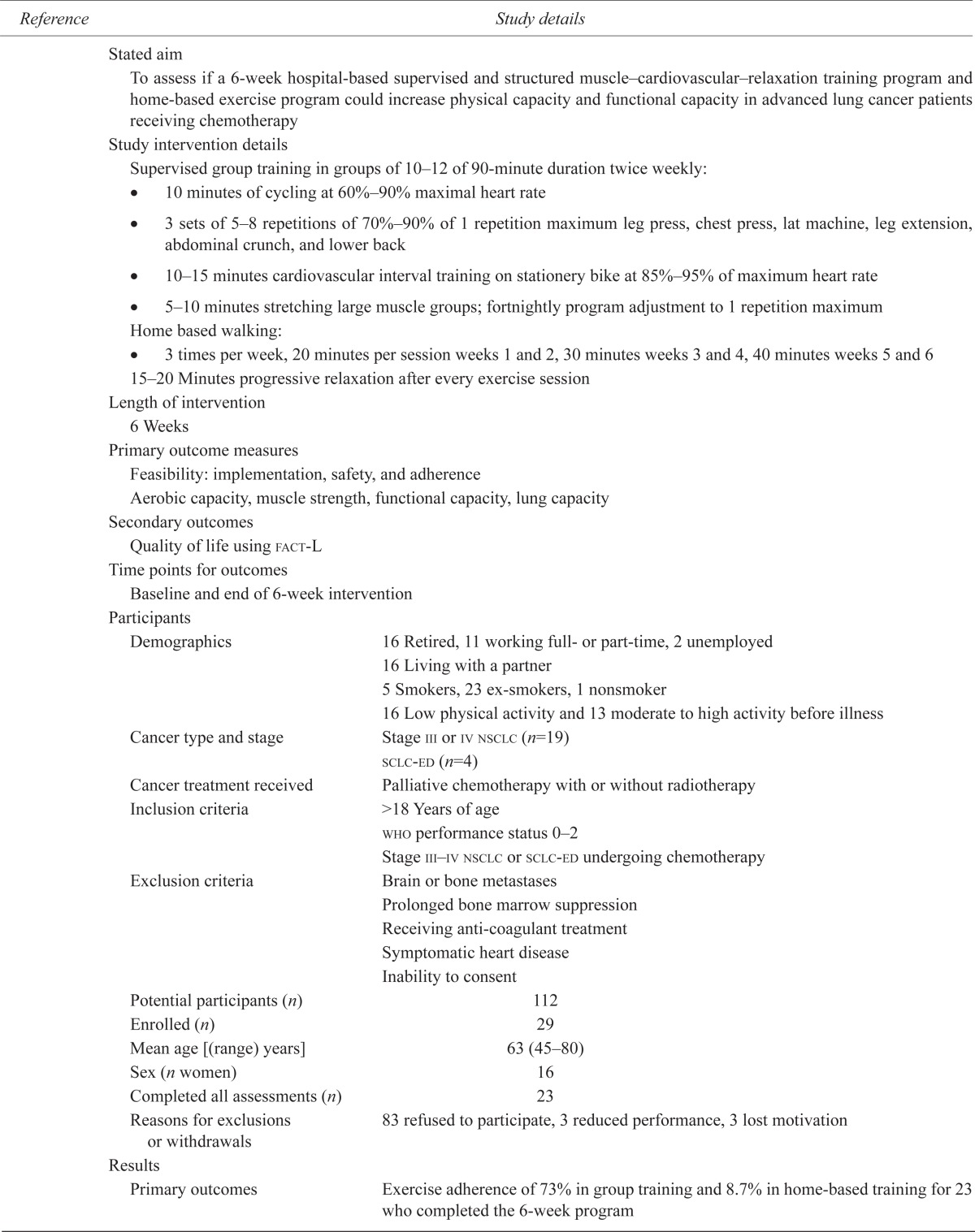

| Quist et al., 201241 | |||

| Study design | |||

| Prospective, single-arm trial | |||

| Start and end date | |||

| October 2008–December 2009 | |||

| Venue | |||

| Hospital- and home-based, Copenhagen, Denmark | |||

| Stated aim | |||

| To assess if a 6-week hospital-based supervised and structured muscle–cardiovascular–relaxation training program and home-based exercise program could increase physical capacity and functional capacity in advanced lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy | |||

| Study intervention details | |||

Supervised group training in groups of 10–12 of 90-minute duration twice weekly:

|

|||

Home based walking:

|

|||

| 15–20 Minutes progressive relaxation after every exercise session | |||

| Length of intervention | |||

| 6 Weeks | |||

| Primary outcome measures | |||

| Feasibility: implementation, safety, and adherence | |||

| Aerobic capacity, muscle strength, functional capacity, lung capacity | |||

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Quality of life using fact-L | |||

| Time points for outcomes | |||

| Baseline and end of 6-week intervention | |||

| Participants | |||

| Demographics | 16 Retired, 11 working full- or part-time, 2 unemployed | ||

| 16 Living with a partner | |||

| 5 Smokers, 23 ex-smokers, 1 nonsmoker | |||

| 16 Low physical activity and 13 moderate to high activity before illness | |||

| Cancer type and stage | Stage iii or iv nsclc (n=19) | ||

| sclc-ed (n=4) | |||

| Cancer treatment received | Palliative chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy | ||

| Inclusion criteria | >18 Years of age | ||

| who performance status 0–2 | |||

| Stage iii–iv nsclc or sclc-ed undergoing chemotherapy | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Brain or bone metastases | ||

| Prolonged bone marrow suppression | |||

| Receiving anti-coagulant treatment | |||

| Symptomatic heart disease | |||

| Inability to consent | |||

| Potential participants (n) | 112 | ||

| Enrolled (n) | 29 | ||

| Mean age [(range) years] | 63 (45–80) | ||

| Sex (n women) | 16 | ||

| Completed all assessments (n) | 23 | ||

| Reasons for exclusions or withdrawals | 83 refused to participate, 3 reduced performance, 3 lost motivation | ||

| Results | |||

| Primary outcomes | Exercise adherence of 73% in group training and 8.7% in home-based training for 23 who completed the 6-week program | ||

| Secondary outcome | Improvements in peak oxygen consumption, 6-minute walk test, muscle strength and emotional well-being on fact-L (p<0.05) | ||

| No significant improvement in overall quality of life | |||

| Conclusions | |||

| Key conclusions of study authors | Program feasible, acceptable, safe and can improve physical and functional capacity and emotional well-being in advanced lung cancer | ||

| Other comments | Contamination with sclc-ed patients (17% of sample) | ||

| Only 2 patients completed home training diaries and undertook walking program (8.7% compliance) | |||

| No consideration of long-term intervention outcomes | |||

epa = eicosapentaenoic acid; nsclc = non-small-cell lung cancer; ecog = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; fact-L = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Lung; sclc-ed = small-cell lung cancer, extensive disease; who = World Health Organization; dha = docosahexaenoic acid; eortc qlq-C30 = European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire.

3.2. Reported Outcomes

3.2.1. Fatigue

Fatigue was a reported outcome in three of the five included studies. Using the validated outcome measurement tools Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Lung37,41 or Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness–Fatigue37, Temel et al.37 and Quist et al.41 found no statistically significant changes in self-reported fatigue in participants who completed a physical activity intervention. The study by van der Meij et al.39 also found no significant differences in fatigue as assessed within the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 30-item quality-of-life questionnaire (eortc qlq-C30: p = 0.57 at week 3, p = 0.95 at week 5).

3.2.2. Appetite

Appetite was a reported outcome in one of the five included studies. No significant differences in appetite as assessed within the eortc qlq-C30 were found in the study by van der Meij39. Appetite was not a formal outcome in the study by Tozer et al.36, but those authors reported that appetite deteriorated significantly (p < 0.05) in participants shortly before death.

3.2.3. Unintentional Weight Loss

Changes in total weight and lean mass were reported in three of the five included studies.

Murphy et al.40 found that most participants receiving an eicosapentaenoic acid (epa) intervention supplement gained or maintained weight and muscle, and improved the quality of their muscle through loss of intermuscular adipose tissue deposits. The improvement was significantly different (p < 0.05) from that in the standard-of-care control group.

Tozer et al.36 found significant mean changes (p < 0.05) in the percentage change of body weight in an intervention group treated with cysteine-rich protein. The control group tended to lose weight, and the active group tended to gain weight. A similar trend (p < 0.05) was also seen in percentage body cell mass as determined by bioelectrical impedance.

In contrast, van der Meij et al.38 found no significant differences in body weight change between groups receiving an active epa–containing intervention and a control supplement. Fat-free mass as determined by bioelectrical impedance declined in both groups, but a statistically larger loss of muscle was observed at 5 weeks in the control group (p < 0.05).

3.2.4. Physical Performance

Physical performance measures were reported in four of the five included studies.

Temel et al.37 reported that participants who completed baseline and post-study assessments increased distance walked in 6 minutes and muscle strength, but statistical significance (p < 0.05) was found only for change in elbow extension, which would indicate increasing power of the triceps brachii.

In an intervention group receiving a cysteine-rich protein supplement, Tozer et al.36 found a significant difference (p < 0.05) in hand-grip force from baseline to 6 months and at the last measurement taken more than 17 days before death. That improvement was not replicated in a group receiving a casein-based control supplement.

Quist et al.41 found an increase in 6-minute walk distance and 1-repetition-maximum weight lift tests in their study completers (p < 0.05), indicating improvements in both exercise capacity and muscle strength.

Van der Meij et al.39 found no significant differences in the physical performance of their intervention and control groups as assessed by hand-grip dynamometry and an accelerometer worn at the hip. Notably, the group receiving the intervention supplement containing epa tended to be more physically active.

3.2.5. Quality of Life

Quality of life (qol) was a reported outcome in three of the five included studies.

Temel et al.37 and Quist et al.41 reported no statistically significant changes in qol in study participants from baseline to post-assessment. However, lung cancer symptoms significantly improved (p < 0.05) in the trial by Tozer et al.36 over the course of the intervention, as measured by that subscale on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Lung. Using the eortc qlq-C30, van der Meij et al.39 reported significantly higher global qol, better social functioning, less nausea and vomiting, fewer financial concerns (p < 0.05), and better physical and cognitive function (p < 0.01) in their intervention group than in their control group.

3.2.6. Recruitment, Attrition, and Adherence to Study Protocol

Low recruitment rates, attrition, and poor adherence to study protocol were reported as major issues in all five of the included studies (see Table i). An increase in plasma fatty acids was reported by van der Meij et al.39 in some control participants, indicative of against-protocol fish-oil supplementation.

3.2.7. Adverse Events

No serious adverse events were recorded for any of the included studies. Tozer et al.40 reported incidences of mild gastrointestinal symptoms thought to be related to the increased protein ingestion in both the intervention and the control group.

3.2.8. Survival

Survival was a reported outcome in two of the five included studies. The median survival of participants in the Temel et al.37 study cohort was 12.98 months, which those authors deemed to be consistent with previous estimates of survival for patients with metastatic lung cancer. Tozer et al.36 found a statistically nonsignificant, but positive trend for survival in the intervention group (p = 0.058), with more participants in the intervention group being alive at 6 months, an observation that they suggested might merit further study.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Summary of Main Results

The aim of the present paper was to review trials of physical activity or nutrition interventions (or both) focusing on the management of fatigue, anorexia, and unintentional weight loss (symptoms of cancer cachexia) in patients with advanced nsclc, and also to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions trialled. Despite an extensive search strategy, only six papers met the inclusion criteria. The included papers detailed five trials with 203 participants. All of the included studies had short intervention and follow-up times, except for the nutrition study undertaken by Tozer et al.36. Shorter studies benefited from reduced attrition rates, but they also prevented the drawing of any conclusions about the long-term effects of the intervention42.

4.1.1. Physical Activity Interventions

The physical activity interventions within the present systematic review37,41 showed that moderate-intensity physical activity interventions were not detrimental to qol in advanced nsclc. Also, some indications of improvement in emotional well-being41 and lung cancer symptoms37 were observed when participants adequately adhered to the intervention guidance.

The beneficial effects of physical activity for cancer survivors have been well established12,43. A recent Cochrane systematic review concluded that, compared with usual care or low-intensity activity interventions, moderate-intensity exercise may have physical, psychosocial, and spiritual benefits for cancer patients receiving cancer treatment44.

In a cross-sectional study of patients receiving palliative care at a regional cancer centre in Canada from November 2006 to May 200745, higher qol scores were self-reported by physically active patients than by those who were sedentary, even when activity levels were significantly below those recommended for the general population. Cancer patients who are more physically able are less likely to have treatment resistant-disease46 and to experience increased life expectancy46–48.

Findings from our systematic review add to the growing body of evidence that promotion of activity is justified, even in the late stages of nsclc21,49,50.

A qualitative study of 20 people with advanced nsclc in the United States found that symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, malaise, and intolerance to cold, coupled with a lack of specific activity guidance from health care professionals and a fear of exercising unsupervised were all significant barriers to increasing or maintaining physical activity51. It is interesting to note that, regardless of tumour stage and functional ability, patients with advanced nsclc have been found to be more likely to engage with and to tolerate moderate- to high-level hospital-based prescribed exercise interventions when they are referred earlier in the course of their cancer treatment52.

4.1.2. Nutrition

The studies included in the present systematic review provided some evidence of beneficial effects from the provision of nutrition support in advanced nsclc. The nutrition interventions used were a cysteine-rich protein supplement36, epa40, and a high-protein energy-dense supplement containing omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids38. Reported benefits included maintenance of weight and muscle mass during active cancer treatment36,53 and improvements in self-reported measures of qol39.

Those benefits were not routinely demonstrated across all studies. Ensuring macro- and micronutrient sufficiency is a vital component of the multimodal active management of cancer cachexia54,55. Although nutrition assessment and counselling are recommended for all weight-losing cancer patients56, those approaches were absent in all of the included studies. Two of the studies used fish-oil supplementation either alone40 or as part of a more complete nutritional supplement38,39. People with advanced cancer are often found to be fatty-acid-deficient, and that deficiency is strongly linked to decreased skeletal muscle mass57. Alterations in food preferences and dietary habits are commonly noted in advanced cancer and may exacerbate nutrient insufficiencies54.

Obesity before diagnosis can be of prognostic advantage in advanced nsclc4, perhaps because of greater lean-mass stores for the body to use56. Weight gain through nutritional supplementation22,58 or appetite stimulation59 have not been shown to have similar survival benefits. A recent systematic review (13 studies with 1414 participants) compared oral-nutrition interventions against standard care for malnourished patients receiving curative or palliative treatment for any cancer diagnosis58. Conclusions were limited because of study heterogeneity, but the authors stated that, although oral-nutrition supplementation increased dietary intake and improved some qol indices such as poor appetite or global qol scores, there was no evidence that nutrition interventions alone can improve survival rates. In the absence of sufficient anabolic drive, additional energy consumed by patients with cancer cachexia syndrome appears to be preferentially stored as fat mass, increasing the metabolic demands imposed on bodily systems and worsening prognosis3,60.

4.2. Completeness and Applicability of Evidence

None of the included studies combined advice with respect to both nutrition management and physical activity. That observation is relevant because lean-tissue anabolism requires sufficiency in both dietary intake and contractile activity61,62.

Recruitment into nutrition or physical activity intervention studies in advanced cancer is low and attrition is high. Withdrawal and drop-out rates often leave very small samples from which to determine any significance of findings. Study recruitment is likely to be influenced not only by the issues that affect all palliative care trials, such as participant identification and heterogeneity63,64, but also by issues specific to exercise engagement or nutritional supplementation and palliative rehabilitation65. The strict criteria for entrance into trials may also be a significant bias. Often, the most unwell people are excluded from studies, making results less applicable to the population as a whole. Interventions that aim to stem weight loss often exclude those for whom the greatest weight loss has already occurred. The new definitions and staging guidance for cancer cachexia6 have led to calls for researchers to consider more carefully suitability and optimal timing of cachexia interventions for people with cancer18. It is hoped that the new criteria proposed by international cancer cachexia experts6 will better define optimal exclusion and inclusion criteria for active interventions.

Positive psychological effects have been found to occur when patients with cancer feel that something rather than nothing is being done to manage their disease66,67, but if interventions are too burdensome, then significant attrition and poor adherence are likely. In essence, what is needed are appropriately timed, individually tailored interventions cognizant of individual’s enablers and barriers to engagement51.

4.3. Quality of the Evidence

The results of our review must be interpreted with caution because of the high risk of bias across the included studies (Table ii). Studies of interventions relating to physical activity and nutrition pose many inherent risks of bias that are not easily controlled for. It is frequently impossible to blind participants to treatment intent, especially where no placebo is available or when the control intervention is standard care63. Advising key stakeholders and potential participants of the study hypothesis, a requirement of research ethics and governance, can also introduce bias through contamination of the control group42,63. The timing of research studies for cachexia symptom management has also attracted criticism, because such studies often occur during the window of expected gain from palliative anticancer therapies68. It is also possible that benefits observed in non-controlled studies may arise purely as a byproduct of increased monitoring and psychosocial support69.

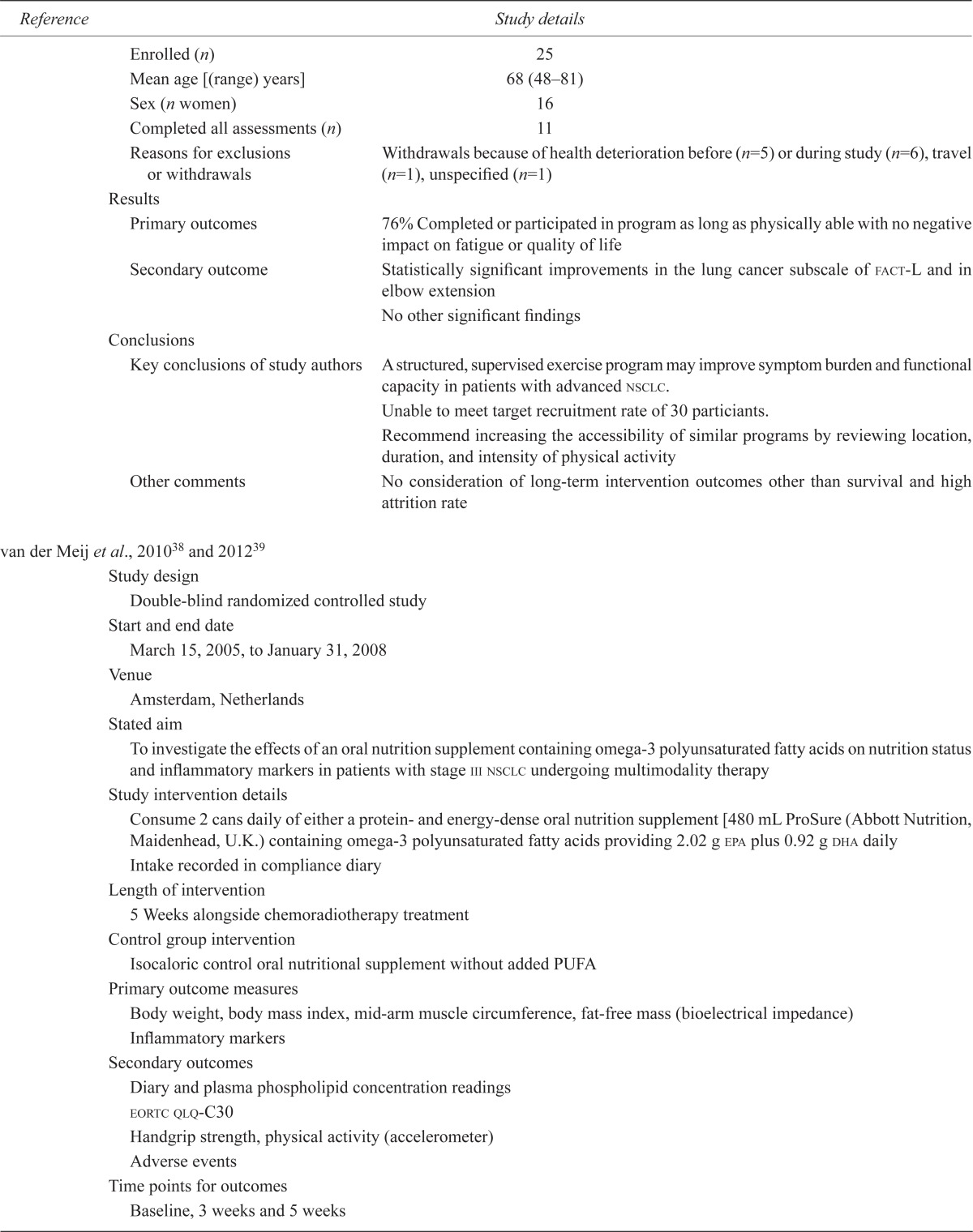

TABLE II.

Risk-of-bias assessment of the included studies

| Reference |

Bias type

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | Performance | Detection | Attrition | Reporting | Other | |

| Tozer et al., 200836 | Low | Low | Low | High | High | High |

| Temel et al., 200937 | High | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| van der Meij et al., 201038 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low to moderate |

| Murphy et al., 201140 | High | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Quist et al., 201241 | High | High | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

5. CONCLUSIONS

5.1. Implications for Practice

The present systematic review suggests that exercise and nutrition interventions are not harmful and may have beneficial effects for unintentional weight loss, physical strength, and functional performance in patients with advanced nsclc. Such improvements must be interpreted with caution, however, because findings were not consistent across the included studies, which were small and at significant risk of bias. The lack of improvement in fatigue scores for all of the interventions is interesting. Improvements in cancer-related fatigue in advanced cancer may be masked through tiredness related to increased exertion. The masking may be particularly pronounced when the outcome measurement is taken immediately after an active physical activity intervention that lacks longer-term follow-up. Pedometers and exercise diaries might be a helpful way of demonstrating gains in function and autonomy where a level of tiredness persists45.

5.2. Implications for Research

More research is required to ascertain optimal physical activity and nutrition interventions in advanced inoperable nsclc. Specifically, the potential benefits of combining physical activity and nutrition counselling have yet to be adequately explored within this population. Outcome measures for assessing interventions in early-stage cancer or in cancer survivors are often inappropriate in advanced cancer, in which progressive functional decline is inevitable. It is vital that researchers separately report outcome measures in a subgroup analysis for participants with advanced illness, even if the findings are statistically nonsignificant. Adopting uniform reporting mechanisms for outcome measures of fatigue and weight loss would also provide an opportunity for meta-analyses of smaller studies70.

6. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the experts who responded to requests for information on their research. The research reported here was funded by the All-Ireland Institute of Hospice and Palliative Care (AIIHPC) and the HSC R&D Division, Public Health Agency, Northern Ireland. AIIHPC is an all-island organization comprising a consortium of hospices and universities, all working to improve the experience of supportive, palliative, and end-of-life care on the island of Ireland by enhancing the capacity to develop knowledge, promote learning, influence policy, and shape practice. The aim is to secure the best care for those approaching end of life.

APPENDIX A: SEARCH STRATEGIES

| ovid | cinahl Plus | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| Step | Search term | Step | Search term |

| 1 | (cachexia or cachexia anorexia syndrome or cachexia associated protein human or cachexia score or “cachexia/case reports” or “cachexia/differential diagnosis” or “cachexia/etiology” or “cachexia/metabolism”).sh. | 1 | “Cachexia” |

| 2 | cachexia {Including Limited Related Terms} | 2 | (MH “Cachexia”) |

| 3 | cachetic OR cachexic {Including Limited Related Terms} | 3 | disease-induced adj starvation |

| 4 | disease-induced adj starvation {Including Limited Related Terms} | 4 | disease-related adj malnutrition |

| 5 | disease-related adj malnutrition {Including Limited Related Terms} | 5 | cachexic or cachectic |

| 6 | wasting {Including Limited Related Terms} | 6 | wasting |

| 7 | (weight adj loss) OR (weight adj3 gain$) OR (weight adj3 los$) {Including Limited Related Terms} | 7 | (MH “Weight Loss+”) |

| 8 | weight loss.sh. | 8 | (MH “Anorexia”) |

| 9 | anorexia.sh. | 9 | (MH “Fatigue+”) OR (MH “Cancer Fatigue”) |

| 10 | fatigue.sh. | 10 | “tiredness” |

| 11 | fatigue {Including Limited Related Terms} | 11 | “fatigue” |

| 12 | weary or weariness {Including Limited Related Terms} | 12 | S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 |

| 13 | tired or tiredness or exhaustion or asthenia {Including Limited Related Terms} | 13 | (MH “Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell Lung”) |

| 14 | lack or loss or lost) adj3 (energy or vigour) {Including Limited Related Terms} | 14 | “lung cancer” |

| 15 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 | 15 | (MH “Lung Neoplasms+”) |

| 16 | lung cancer.sh. | 16 | S13 or S14 or S15 |

| 17 | lung adj cancer {Including Limited Related Terms} | 17 | (MH “Nutrition+”) |

| 18 | nsclc {Including Limited Related Terms} | 18 | (MH “Nutritional Assessment”) |

| 19 | 16 or 17 or 18 | 19 | (MH “Diet Therapy+”) |

| 20 | nutrition.sh. | 20 | “nutrition” |

| 21 | nutrition assessment.sh. | 21 | (MH “Diet+”) |

| 22 | nutrition therapy.sh. | 22 | “diet” |

| 23 | food.sh. | 23 | S17 or S18 or S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 |

| 24 | diet$ {Including Limited Related Terms} | 24 | (MH “Exercise+”) |

| 25 | diet {Including Limited Related Terms} | 25 | (MH “Physical Fitness+”) OR “physical fitness” OR (MH “Physical Activity”) |

| 26 | diet.sh. | 26 | (MH “Sports+”) |

| 27 | 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 | 27 | “sport” |

| 28 | exercise.sh. | 28 | “exercise training” |

| 29 | physical fitness.sh. | 29 | (MH “Fitness Centers”) |

| 30 | sports.sh. | 30 | S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 or S28 or S29 |

| 31 | training.sh. | 31 | S23 or S30 |

| 32 | exercise {Including Limited Related Terms} | 32 | S12 and S16 and S31 |

| 33 | physical adj fitness {Including Limited Related Terms} | ||

| 34 | sport {Including Limited Related Terms} | ||

| 35 | physical adj training {Including Limited Related Terms} | ||

| 36 | 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 | ||

| 41 | 15 and 19 | ||

| 42 | 27 or 36 | ||

| 43 | 41 and 42 | ||

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no financial conflict of interest exists.

8. REFERENCES

- 1.Tsai JS, Wu CH, Chiu TY, Hu WY, Chen CY. Symptom patterns of advanced cancer patients in a palliative care unit. Palliat Med. 2006;20:617–22. doi: 10.1177/0269216306071065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbertson–White S, Aouizerat BE, Jahan T, Miaskowski C. A review of the literature on multiple symptoms, their predictors, and associated outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2011;9:81–102. doi: 10.1017/S147895151000057X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:629–35. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang R, Cheung MC, Pedroso FE, Byrne MM, Koniaris LG, Zimmers TA. Obesity and weight loss at presentation of lung cancer are associated with opposite effects on survival. J Surg Res. 2011;170:e75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Portenoy RK. Treatment of cancer pain. Lancet. 2011;377:2236–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:489–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blum D, Omlin A, Baracos VE, et al. on behalf of the European Palliative Care Research Collaborative Cancer cachexia: a systematic literature review of items and domains associated with involuntary weight loss in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;80:114–44. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly DW, Gavin AT, Comber H. Cancer in Ireland 1994–2004: A Comprehensive Report. Cork, Ireland: National Cancer Registry, Ireland; Northern Ireland Cancer Registry; 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cancer Research UK . Home > News & Resources > CancerStats > Types of cancer > Lung cancer > Incidence. Lung cancer incidence statistics [Web page] London, UK: Cancer Research UK; n.d. [Most recent version available at: http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/lung/incidence; cited August 19, 2011] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA. Non–small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:584–94. doi: 10.1097/00000372-197900120-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baracos VE, Reiman T, Mourtzakis M, Gioulbasanis I, Antoun S. Body composition in patients with non–small cell lung cancer: a contemporary view of cancer cachexia with the use of computed tomography image analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1133S–7S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.28608C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granger CL, McDonald CF, Berney S, Chao C, Denehy L. Exercise intervention to improve exercise capacity and health related quality of life for patients with non–small cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer. 2011;72:139–53. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Chu QS, Baracos VE, Reiman T, Mazurak VC. Supplementation with fish oil increases first-line chemotherapy efficacy in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:3774–80. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chasen MR, Dippenaar AP. Cancer nutrition and rehabilitation—its time has come! Curr Oncol. 2008;15:117–22. doi: 10.3747/co.v15i3.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glare P, Jongs W, Zafiropoulos B. Establishing a cancer nutrition rehabilitation program (cnrp) for ambulatory patients attending an Australian cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:445–54. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0834-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granda–Cameron C, DeMille D, Lynch MP, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to manage cancer cachexia. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:72–80. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.72-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watkins F, Tulloch S, Bennett C, Webster B, McCarthy C. A multimodal, interdisciplinary programme for the management of cachexia and fatigue. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2012;18:85–90. doi: 10.1080/07357900701560612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fearon KCH. The 2011 espen Arvid Wretlind lecture: cancer cachexia: the potential impact of translational research on patient-focused outcomes. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:577–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Oxford U.K.: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Ver. 5.1.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (casp) Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Making Sense of Evidence About Clinical Effectiveness—12 Questions to Help You Make Sense of a Cohort Study. Oxford, U.K.: CASP; 2010. [Available online at: http://www.casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/CASP_Cohort_Appraisal_Checklist_14oct10.pdf; cited June 11, 2012] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheville AL, Kollasch J, Vandenberg J, et al. A home-based exercise program to improve function, fatigue, and sleep quality in patients with stage iv lung and colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:811–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldwin C, Spiro A, McGough C, et al. Simple nutritional intervention in patients with advanced cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, non-small cell lung cancers or mesothelioma and weight loss receiving chemotherapy: a randomised controlled trial. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:431–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen AH, Vinther A, Poulsen LL, Mellemgaard A. Do patients with lung cancer benefit from physical exercise? Acta Oncol. 2011;50:307–13. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.529461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer JD, Capra S. Nutrition intervention improves outcomes in patients with cancer cachexia receiving chemotherapy—a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:270–4. doi: 10.1007/s00520-004-0746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewey A. An Investigation of Practical Management of Cachexia in Advanced Cancer Patients. 2006. [PhD thesis]. Portsmouth, U.K.: University of Portsmouth; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fearon KC, Barber MD, Moses AG, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study of eicosapentaenoic acid diester in patients with cancer cachexia. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3401–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madeddu C, Maccio A, Astara G, et al. Open phase ii study on efficacy and safety of an oral amino acid functional cluster supplementation in cancer cachexia. Mediterr J Nutr Metab. 2010;3:165–72. doi: 10.1007/s12349-010-0016-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oldervoll LM, Loge JH, Lydersen S, et al. Physical exercise for cancer patients with advanced disease: a randomized controlled trial. Oncologist. 2011;16:1649–57. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peddle–McIntyre CJ, Bell G, Fenton D, McCargar L, Courneya KS. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of progressive resistance exercise training in lung cancer survivors. Lung Cancer. 2012;75:126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riesenberg H, Lübbe AS. In-patient rehabilitation of lung cancer patients—a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:877–82. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0727-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spruit MA, Janssen PP, Willemsen SC, Hochstenbag MM, Wouters EF. Exercise capacity before and after an 8-week multidisciplinary inpatient rehabilitation program in lung cancer patients: a pilot study. Lung Cancer. 2006;52:257–60. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerchietti LC, Navigante AH, Castro MA. Effects of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic n-3 fatty acids from fish oil and preferential Cox-2 inhibition on systemic syndromes in patients with advanced lung cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2007;59:14–20. doi: 10.1080/01635580701365068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deutz NE, Safar A, Schutzler S, et al. Muscle protein synthesis in cancer patients can be stimulated with a specially formulated medical food. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:759–68. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanchez K, Turcott J, Juarez E, Villanueva G, Dorantes Y, Arrieta O. The effect of an oral nutritional supplement with eicosapentaenoic acid on body composition, energy intake, quality of life and survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer [abstract] Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:S637. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)72457-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shannon V, Faiz S, Maldonado J. Impact and feasibility of pulmonary rehabilitation on performance status among lung cancer patients during cancer therapy [abstract] J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2010;30:278. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tozer RG, Tai P, Falconer W, et al. Cysteine-rich protein reverses weight loss in lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:395–402. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Temel JS, Greer JA, Goldberg S, et al. A structured exercise program for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:595–601. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819d18e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Meij BS, Langius JA, Smit EF, et al. Oral nutritional supplements containing (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids affect the nutritional status of patients with stage iii non-small cell lung cancer during multimodality treatment. J Nutr. 2010;140:1774–80. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.121202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Meij BS, Langius JA, Spreeuwenberg MD, et al. Oral nutritional supplements containing n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids affect quality of life and functional status in lung cancer patients during multimodality treatment: an rct. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:399–404. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Chu QS, Baracos VE, Reiman T, Mazurak VC. Nutritional intervention with fish oil provides a benefit over standard of care for weight and skeletal muscle mass in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cancer. 2011;117:1775–82. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quist M, Rørth M, Langer S, et al. Safety and feasibility of a combined exercise intervention for inoperable lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a pilot study. Lung Cancer. 2012;75:203–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans CJ, Harding R, Higginson IJ, on behalf of morecare “Best practice” in developing and evaluating palliative and end-of-life care services: a meta-synthesis of research methods for the morecare project. Palliat Med. 2013;11:111. doi: 10.1177/0269216312467489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cramp F, Byron–Daniel J. Exercise for the management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;11:CD006145. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Geigle PM, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007566. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90261-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lowe SS, Watanabe SM, Baracos VE, Courneya KS. Determinants of physical activity in palliative cancer patients: an application of the theory of planned behavior. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kasymjanova G, Correa JA, Kreisman H, et al. Prognostic value of the six-minute walk in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:602–7. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819e77e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maddocks M, Byrne A, Johnson CD, Wilson RH, Fearon KC, Wilcock A. Physical activity level as an outcome measure for use in cancer cachexia trials: a feasibility study. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1539–44. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0776-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones LW, Hornsby WE, Goetzinger A, et al. Prognostic significance of functional capacity and exercise behavior in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:248–52. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lowe SS, Watanabe SM, Courneya KS. Physical activity as a supportive care intervention in palliative cancer patients: a systematic review. J Support Oncol. 2009;7:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adamsen L, Quist M, Midtgaard J, et al. The effect of a multidimensional exercise intervention on physical capacity, well-being and quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:116–27. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0864-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheville AL, Dose AM, Basford JR, Rhudy LM. Insights into the reluctance of patients with late-stage cancer to adopt exercise as a means to reduce their symptoms and improve their function. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dalzell MA, Kreisman H, Dobson S, et al. Exercise in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (nsclc): compliance and population characteristics of patients referred to the McGill Cancer Nutrition–Rehabilitation Program (cnrp) [abstract 8631] J Clin Oncol. 2006;24 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Chu QS, Baracos VE, Reiman T, Mazurak VC. Nutritional intervention with fish oil provides a benefit over standard of care for weight and skeletal muscle mass in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cancer. 2011;117:1775–82. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hutton JL, Martin L, Field CJ, et al. Dietary patterns in patients with advanced cancer: implications for anorexia–cachexia therapy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1163–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.2001.01039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ravasco P, Monteiro Grillo I, Camilo M. Cancer wasting and quality of life react to early individualized nutritional counselling! Clin Nutr. 2007;26:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baracos VE, Parsons HA. Metabolism and physiology. In: Del Fabbro E, Baracos VE, Demark–Wahnefried W, Bowling T, Hopkinson J, Bruera E, editors. Nutrition and the Cancer Patient. Oxford, U.K: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 7–18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murphy RA, Mourtzakis M, Chu QS, Reiman T, Mazurak VC. Skeletal muscle depletion is associated with reduced plasma (n-3) fatty acids in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Nutr. 2010;140:1602–6. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.123521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baldwin C, Spiro A, Ahern R, Emery PW. Oral nutritional interventions in malnourished patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:371–85. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berenstein G, Ortiz Z. Megestrol acetate for treatment of anorexia–cachexia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004310. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004310.pub2. [Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;3:CD004310] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harvie MN, Howell A, Thatcher N, Baildam A, Campbell I. Energy balance in patients with advanced nsclc, metastatic melanoma and metastatic breast cancer receiving chemotherapy—a longitudinal study. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:673–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khamoui AV, Kim JS. Candidate mechanisms underlying effects of contractile activity on muscle morphology and energetics in cancer cachexia. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2012;21:143–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Del Fabbro E, Hui D, Dalal S, Dev R, Nooruddin ZI, Bruera E. Clinical outcomes and contributors to weight loss in a cancer cachexia clinic. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1004–8. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grande GE, Todd CJ. Why are trials in palliative care so difficult? Palliat Med. 2000;14:69–74. doi: 10.1191/026921600677940614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hagen NA, Wu JS, Stiles CR. A proposed taxonomy of terms to guide the clinical trial recruitment process. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:102–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.11.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eva G, Wee B. Rehabilitation in end-of-life management. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2010;4:158–62. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32833add27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berendes D, Keefe FJ, Somers TJ, Kothadia SM, Porter LS, Cheavens JS. Hope in the context of lung cancer: relationships of hope to symptoms and psychological distress. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:174–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pinquart M, Fröhlich C, Silbereisen RK. Optimism, pessimism, and change of psychological well-being in cancer patients. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:421–32. doi: 10.1080/13548500601084271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Azzoli CG, Temin S, Giaccone G. 2011 Focused update of 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update on chemotherapy for stage iv non-small-cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:63–6. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jacobsen J, Jackson V, Dahlin C, et al. Components of early outpatient palliative care consultation in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:459–64. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Payne C, Wiffen PJ, Martin S. Interventions for fatigue and weight loss in adults with advanced progressive illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:008427. doi: 10.1159/000093854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]