Abstract

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) in internal migrants is one of three threats for TB control in China. To address this threat, a project was launched in eight of the 19 districts of Shanghai in 2007 to provide transportation subsidies and living allowances for all migrant TB cases. This study aims to determine if this project contributed to improved TB control outcomes among migrants in urban Shanghai.

Methods

This was a community intervention study. The data were derived from the TB Management Information System in three project districts and three non-project districts in Shanghai between 2006 and 2010. The impact of the project was estimated in a difference-in–difference (DID) analysis framework, and a multivariable binary logistic regression analysis.

Results

A total of 1872 pulmonary TB (PTB) cases in internal migrants were included in the study. The treatment success rate (TSR) for migrant smear-positive cases in project districts increased from 59.9% in 2006 to 87.6% in 2010 (P < 0.001). The crude DID improvement of TSR was 18.9%. There was an increased probability of TSR in the project group before and after the project intervention period (coefficient = 1.156, odds ratio = 3.178, 95% confidence interval: 1.305–7.736, P = 0.011).

Conclusion

The study showed the project could improve treatment success in migrant PTB cases. This was a short-term programme using special financial subsidies for all migrant PTB cases. It is recommended that project funds be continuously invested by governments with particular focus on the more vulnerable PTB cases among migrants.

Introduction

China is one of the 22 highest tuberculosis (TB) burden countries in the world1 with an estimated 0.9–1.2 million TB cases in 2010.2 There is a large amount of rural-to-urban migration in China with over 200 million people relocating to seek better incomes and living conditions. TB in the large internal migrant population (about 221 million in 2010) has been demonstrated as one of the major threats to TB control in China.3 Many studies have found that internal migrants have lower incomes compared to the local residents, have poor access to health and social security systems, are highly mobile and are therefore more vulnerable to TB. These factors result in a lower proportion of suspected TB cases completing diagnostic evaluation and an even lower proportion of successful treatment in internal migrants.4–10 Information from the China TB Information Management System (TB-IMS) in 2005 showed a higher proportion of migrants among notified TB cases in big cities, ranging from 40–80%, and a treatment completion rate among migrants of around 60% compared with over 85% among local residents.11

Shanghai is the largest city by population in China (over 23 million in 2010), and 39% of the population are internal migrants.12,13 Compared with local registered residents, migrants have restricted access to TB control services and social protection.6,14–16 To improve TB control for migrants, a five-year financing project of transportation subsidies and living allowances for patients was launched in eight of 19 districts in Shanghai (one district in 2006 and seven districts in 2007). This study aims to determine if the transportation subsidies and living allowances contributed to improved TB treatment outcomes among internal migrants in Shanghai.

Methods

Study setting

There were eight project districts in Shanghai. The project provided transportation subsidies and living allowances of US$14.63 and US$4.39 a month, respectively, for all migrant TB cases (non-local official household registered resident TB cases) in the project districts. The services they received were the same as those in non-project districts. In 2010, there were 2439 migrant pulmonary TB (PTB) cases receiving the subsidies.

Three project and three non-project districts were compared. Sample size calculations estimated samples of 108 for project groups and 484 for non-project groups (a = 0.05, b = 0.10). It was estimated there are 600 migrant TB cases in three districts a year. Three project and three non-project districts in Shanghai were selected by geographic location: one central urban district (A district), one suburb district (B district) and one district between A district and B district (C district) for both the project and non-project groups.

Project B district initiated the project on 1 October 2006; to minimize the effect of this bias, the cases from October to December 2006 in B district were eliminated along with a quarter of the population.

Study design

This was a community intervention study; quantitative methods were used to evaluate the effect of the project. The data of PTB cases were obtained from the China TB-IMS for 2006 and 2010.

Treatment success rate (TSR) was defined as the proportion of a cohort of TB cases registered in the TB-IMS as being treated under directly observed treatment, short-course (DOTS) in a given year whom successfully completed treatment. Treatment success included those with bacteriologic evidence of success (“cured”) or without bacteriologic evidence (“treatment completed”).17 TSR was used to determine the success of the project between smear-positive PTB and smear-negative PTB cases.18

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the TB cases from the surveillance data. For dichotomous data, the differences between TB treatment outcomes of project and non-project districts were tested using χ2 tests. To assess the project intervention effect on migrant smear-positive PTB cases, a difference-in-difference (DID)estimation framework was used. To determine the impact of the intervention, a crude double difference of TSR was calculated: ([TSRproj,2010–TSRproj,2006]–[TSRnon-proj,2010–TSRnon-proj,2006]). This assumed that the change of TSR in the non-project districts reflects what would happen in the project districts in the absence of the project.

A multivariate logistic regression model was then performed to estimate the association among the probability of being successfully treated (P[Y = 1]) and the DID impact estimator (the interaction on being a project recipient and year of registration) and some other independent variables. Here the dependent variable Y indicated “treatment success or not” (using value one for treatment success, zero for otherwise).The independent variables were basic personal information available in TB-IMS, including year of patient registration (2006 or 2010), patient site (non-project and project), two-way interactions between patient site and year of registration, sex, age, job (professional, managerial, skilled or partially skilled, housekeeper or unemployed, children or youth, retired and others) and TB type (initial or re-treated cases). Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20.0 and STATA version 12.

Results

Migrant PTB notifications

There were a total of 909 and 963 migrant PTB cases reported in TB-IMS in 2006 and 2010, respectively. Among these, 42–45% were smear-positive cases. The case notification rate for smear-positive PTB in migrants was more than two times that of local residents in 2006 (27.1 per 100 000 compared with 12.1 per 100 000) and 1.3 times higher in 2010 (16.2 per 100 000 compared with 11.9 per 100 000).

The migrant groups in project districts had a smear-positive notification rate of 26.8 per 100 000 in 2006, lower than for migrants in non-project districts at 28.2 per 100 000. In 2010, this rate decreased by 33.3% in the project districts to 17.9 per 10 000. In contrast, it decreased by 58.9% in non-project districts to 11.6 per 100 000.

In both 2006 and 2010, nearly 90% of new PTB cases in migrants were diagnosed and treated for the first time, compared with about 85% in local resident groups.

Characteristics of migrant PTB cases

Among the migrant PTB patients, 515 (27.5%), 1009 (53.9%) and 348 (18.6%) cases were registered in A, B and C districts, respectively. Some characteristics of the 1872 migrant PTB cases were similar in both project and non-project districts in both 2006 and 2010. About 60% of all four groups were male with just over 65% cases aged 15–34 years (Table 1). Approximately 40% of migrant PTB cases in all groups combined were skilled or partially skilled employees (e.g. worker, farmer, service personnel), 25% were housekeepers or unemployed migrants and 4% were children, youth and retired people. However, job structure comparison between project and non-project districts showed that there was a significant difference both in 2006 and 2010 (P < 0.001 for both).

Table 1. Characteristics of migrant PTB cases by project and non-project districts, Shanghai, China, 2006 and 2010.

| Variable | 2006 | 2010 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project districts | Non-project | P-value* | Project districts | Non-project | P-value* | |||||

| (n = 691) | % | (n = 281) | % | (n = 734) | % | (n = 229) | % | |||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Smear-positive | 312 | 45.2 | 93 | 42.7 | 0.519 | 330 | 45.0 | 75 | 32.8 | 0.001 |

| Smear-negative | 379 | 54.8 | 125 | 57.3 | 404 | 55.0 | 154 | 67.2 | ||

| Therapy | ||||||||||

| Initially treated | 608 | 88.0 | 194 | 89.0 | 0.689 | 656 | 89.4 | 202 | 88.2 | 0.622 |

| Re-treated | 83 | 12.0 | 24 | 11.0 | 78 | 10.6 | 27 | 11.8 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 419 | 60.6 | 131 | 60.1 | 0.886 | 462 | 62.9 | 135 | 59.0 | 0.277 |

| Female | 272 | 39.4 | 87 | 39.9 | 272 | 37.1 | 94 | 41.0 | ||

| Age | ||||||||||

| below 15 | 4 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.324 | 7 | 1.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.081 |

| 15–24 | 193 | 27.9 | 54 | 24.8 | 246 | 33.5 | 92 | 40.2 | ||

| 25–34 | 249 | 36.0 | 81 | 37.2 | 249 | 33.9 | 66 | 28.8 | ||

| 35–44 | 134 | 19.4 | 42 | 19.3 | 107 | 14.6 | 38 | 16.6 | ||

| 45–54 | 53 | 7.7 | 11 | 5.0 | 57 | 7.8 | 15 | 6.6 | ||

| 55–64 | 35 | 5.1 | 20 | 9.2 | 49 | 6.7 | 7 | 3.1 | ||

| 65 and above | 23 | 3.3 | 9 | 4.1 | 19 | 2.6 | 10 | 4.4 | ||

| Occupation | ||||||||||

| Professional | 7 | 1.0 | 3 | 1.4 | < 0.001 | 9 | 1.2 | 7 | 3.1 | < 0.001 |

| Managerial | 28 | 4.1 | 26 | 11.9 | 43 | 5.9 | 13 | 5.7 | ||

| Skilled or partially skilled | 282 | 40.8 | 71 | 32.6 | 330 | 45.0 | 72 | 31.4 | ||

| Housekeeper or unemployed | 226 | 32.7 | 40 | 18.3 | 179 | 24.4 | 48 | 21.0 | ||

| Children and youth | 26 | 3.8 | 7 | 3.2 | 24 | 3.3 | 15 | 6.6 | ||

| Retired | 25 | 3.6 | 20 | 9.2 | 25 | 3.4 | 9 | 3.9 | ||

| Others | 97 | 14.0 | 51 | 23.4 | 124 | 16.9 | 65 | 28.4 | ||

* P-values are for χ2 tests of association between district type (project versus non-project) and characteristics factors.

Treatment outcomes of migrant PTB cases

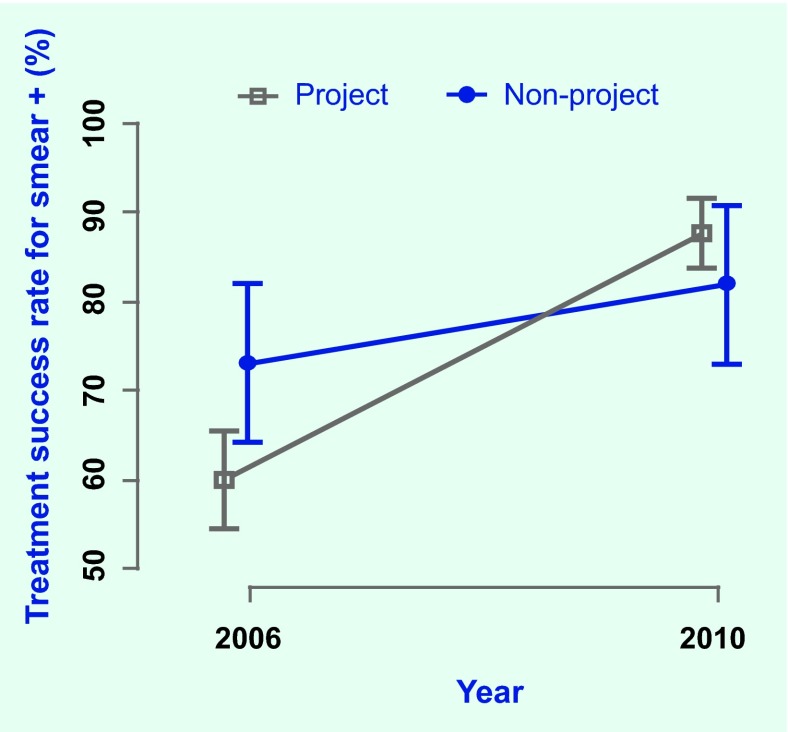

In 2006, TSR of smear-positive cases in project districts was 59.9%, lower than in non-project districts at 73.1% and significantly different (P = 0.021). In 2010, TSR in project districts rose to 87.6%, significantly higher than in 2006 (P < 0.001) and was appreciably higher than non-project districts in 2010 at 81.9%, although this was not significantly different (P = 0.205; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Treatment success rates for smear-positive migrant PTB cases, Shanghai, China, 2006 and 2010

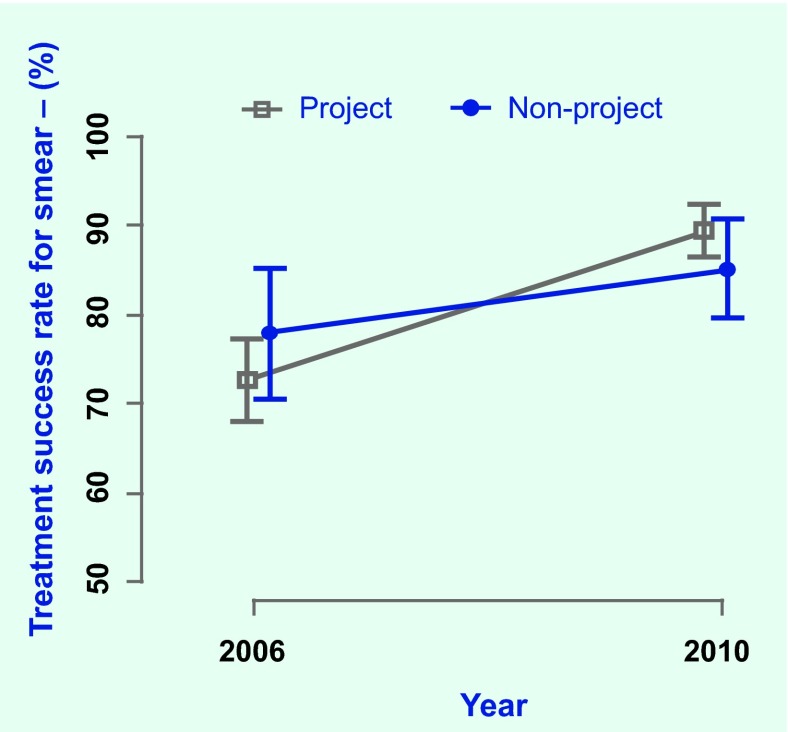

In 2006, TSR of smear-negative PTB cases in project districts was 73.1%, lower than that in non-project districts at 78.4%. In 2010, TSR in project districts increased to 89.8%, higher than that in non-project districts at 85.6%, but this was not significantly different (P = 0.165; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Treatment success rates for smear-negative migrant PTB cases, Shanghai, China, 2006 and 2010

The crude average double difference of TSR was 18.9% (Fig. 1). In the logistic regression model, the predictor of interaction on being a project recipient and year of registration was significantly associated with a higher probability of TSR (odds ratio [OR] = 3.178; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.305–7.736; P = 0.011) after adjustment for all other variables. The odds, the relative possibility of PTB treatment success, for those in project districts in 2010 (site*year = 1) was 3.178 times as high as those in non-project districts in 2006, those in project districts in 2006, and those in non-project districts in 2010 (site*year = 0) (Table 2).

Table 2. Multivariable logistic regression analysis on the treatment success rates for migrant smear-positive cases by confounding factors, Shanghai, China, 2006 and 2010.

| Variables | β | Wald | P-value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient site (non-project = 0) | –0.725 | –2.63 | 0.009 | 0.484 | (0.282–0.831) |

| Patient site * year (year, 2006 = 0) | 1.156 | 2.55 | 0.011 | 3.178 | (1.305–7.736) |

| Sex (female = 0) | –0.403 | –2.13 | 0.033 | 0.668 | (0.461–0.969) |

| Patient type(new cases = 0) | –0.588 | –2.59 | 0.010 | 0.555 | (0.356–0.867) |

| Occupationretired * (skilled or partly skilled = 0) | –1.040 | –2.63 | 0.009 | 0.354 | (0.163–0.768) |

| Constant | 2.026 |

a Occupation is used as dummy variables in regression analysis. All other occupation fields are not included in the regression model.

CI – confidence interval; OR – odds ratio.Further analysing the interaction on being a project recipient and year of registration by stratified analysis, the difference of TSR before and after project intervention periods (post-baseline) was not significantly different for cases in the non-project districts (OR = 1). However, we estimated the increased probability of TSR in the project group before and after the project intervention period (coefficient = 1.156; OR = 3.178; 95% CI: 1.305–7.736; P = 0.011) (Table 3).

Table 3. Difference-in-difference estimates for the contribution of the project on the treatment success rates for smear-positive migrant PTB cases, Shanghai, China, 2006 and 2010.

| Xtime = 0 | Xtime = 1 | X([time = 1] – [time = 0]) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xproject = 0 | Xna | Xna | 0 | 1 |

| Xproject = 1 | –0.725+Xna | –0.725+1.156+Xna | 1.156 | 0.011 |

a Xn is the part of the estimation model (Logit[YTSR]): 2.026–0.403xsex–0.588xtherapy–1.040xjobretired.

Discussion

This study indicated that transportation subsidies and living allowances played a role in improving treatment outcomes of migrant PTB patients in Shanghai. In project districts, the TSR for migrant smear-positive PTB cases reached 87.6% in 2010. The DID improvement of TSR, which compares the crude improvement of the project districts with the non-project districts, was 18.9%. Further, the result of the multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that the project intervention was positively associated with treatment success outcomes (OR = 3.178; 95% CI: 1.305–7.736).

In this study, the financial support was designed to promote better compliance to quality TB care in the internal migrant population. Previous studies have found that a large proportion of PTB cases in urban areas occurs in migrants.19–22 Financial constraints were reported as the biggest barriers to TB services and compliance to normative treatment courses among migrant patients.23,24 The results of this study are in agreement with several studies in China that revealed transportation subsidies and living allowances could improve treatment adherence in migrant PTB cases in some urban areas in China.25,26 The reasons for increased TSR might be that the transportation subsidies and living allowances reduced the disease burden for migrant PTB cases and encouraged them to stay in Shanghai to complete the treatment course27; and the subsidies may also improve their trust in TB control policies, services and health providers. However, in practice, some TB control staff and PTB patients mentioned that the project subsidies were too little for the patients who really needed them to support their TB treatment; for some migrants with high income, the effect was limited.

Despite the success of this programme, certain challenges affecting project sustainability should not be overlooked. The initial project was made possible through a governmental special financing programme. According to the World Health Organization Global TB Control Programme, making DOTS pro-poor is justified on epidemiological, economic and equity grounds and will significantly contribute to the achievement of the global targets for TB.28 It is suggested that national and local governments give priority to poverty reduction strategies in TB control. Improvements could include building a sustainable mechanism to continue and increase the investment amount; cooperating with other related departments, including departments of civil affairs, labour and social security, and nongovernmental organizations to identify the more vulnerable migrant PTB cases; specifying the amount of subsidies for migrant PTB cases on different economic levels; and raising the amount of the subsidies moderately to relieve the burden for the migrant PTB cases who really need them.

This study had some limitations. First, it was a retrospective study and secondary data were used, so the data set was limited in its ability to identify certain variables affecting TSR such as personal economic situation; education level; and regional, social, economic and ecological conditions. Second, selection of districts in project and non-project groups was based more on geography, although the analysis results in project and non-project groups in baseline showed that their background information was similar (except for occupation). Third, the non-project group did not reach the required sample size because some cases visited a doctor and registered in a municipal-level TB hospital in a non-project district but lived elsewhere. Their treatment and treatment outcome information was not completed, and they need to be retrieved for a further study.

Conclusion

Transportation subsidies and living allowances contributed to the improvement of TB treatment success among internal migrants TB cases in Shanghai. Despite limitations with using surveillance data, our study did allow for the assessment of the effectiveness of the project.

The project was a short-term programme with special financing subsidies for migrant PTB cases. Meanwhile, the number of migrant PTB cases is growing in urban areas; thus, a similar long-term investment by government is recommended. The project provided the same subsidies for each migrant PTB case in project districts without recognizing the poor or other vulnerable migrant groups who need more financial aid to support their TB treatment. Therefore, the priority interventions are to identify and ensure adequate subsidies for vulnerable groups.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Zhang Hui (National Center for TB Control and Prevention, China Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDCs]), Dr Fabio Scano and Dr Liu Yuhong (WHO China country office) for their opinions on the study proposal. We would like to thank the local TB control administrators in six district CDCs for their coordination and active responses. Thanks to members of our research group for their indispensable contribution to the study. Sincere thanks also for instructive comments given by Dr Nobuyuki Nishikiori (WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for the Western Pacific

References

- 1.Global tuberculosis report 2012. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75938/1/9789241564502_eng.pdf accessed 20 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global tuberculosis report 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2011/gtbr11_full.pdf accessed 19 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long Q, et al. Barriers to accessing TB diagnosis for rural-to-urban migrants with chronic cough in Chongqing, China: a mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research. 2011;16:341. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ni Z, et al. TB detection and treatment among domestic migrants in Minghang district, Shanghai. Journal of Shanghai Preventive Medicine. 2003;9:448–53. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Wang Y. Study on the impact factors on migrant TB cases management. Foreign Medicine. Social Medicine Branch. 2005;22:53–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, et al. Barriers in accessing to tuberculosis care among non-residents in Shanghai: a descriptive study of delays in diagnosis. European Journal of Public Health. 2007;17:419–23. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, et al. Treatment seeking for symptoms suggestive of TB: comparison between migrants and permanent urban residents in Chongqing, China. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2008;13:927–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li X, et al. Active pulmonary tuberculosis case detection and treatment among floating population in China: an effective pilot. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Public Health. 2010;12:811–5. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jie R, et al. The social support state of the tuberculosis patient in floating population. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science. 2006;5:437–9. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Wei X, Li H. Study on barriers to anti-TB treatment for rural-to-urban migrant TB patients in Shanghai. Journal of the Chinese Anti-Tuberculosis Association. 2009;6:337–40. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 11.China TB Information Management System. Beijing: China National TB Control Center; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Communiqué of the national bureau of statistics of People’s Republic of China on major figures of the 2010 population census. Beijing: National Bureau of Statistics of China; 2011. http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/newsandcomingevents/t20110429_402722516.htm accessed 1 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Development status and characteristics of the provinces and cities outside Shanghai resident population. Shanghai: Municipal Statistics Bureau; 2011. http://www.stats-sh.gov.cn/fxbg/201109/232741.html [In Chinese] accessed 1 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao DH, Li HD, Xu B. [Knowledge of tuberculosis amongst service industry workers of the floating population in Changning district, Shanghai] Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases. 2005;28:188–91. [In Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang L, et al. A descriptive study on diagnostic delays and factors impacting accessibility to diagnosis among TB patients in floating population in Shanghai. Journal of the Chinese Anti-Tuberculosis Association. 2007;2:127–9. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jie R, et al. The social support state of the tuberculosis patient in floating population. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science. 2006;5:437–9. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Development Group. Indicators for monitoring the Millennium Development Goals – definitions, rationale, concepts and sources. New York: United Nations; 2003. http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Resources/Attach/Indicators/HandbookEnglish.pdf accessed 1 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Compendium of indicators for monitoring and evaluation national tuberculosis programs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2004/WHO_HTM_TB_2004.344.pdf accessed 1 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin BC, Shao JP. Epidemiological characteristics of 2271 cases of pulmonary tuberculosis in floating population of Wenling, Zhejiang. Disease Surveillance. 2012;27:592–4. http://www.jbjc.org/EN/abstract/abstract7539.shtml accessed 10 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du X, Liu EY, Cheng SM. Characteristics of new smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis in floating population in 2010. Journal of the Chinese Anti-Tuberculosis Association. 2011;8:461–6. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei JF, et al. The migrant tuberculosis problems and control in China. China Practical Medicine. 2007;2:155–6. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li T, et al. Impact of new migrant populations on the spatial distribution of tuberculosis in Beijing. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2011;15:163–8, i–iii. [In Chinese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou C, et al. Adherence to tuberculosis treatment among migrant pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Shandong, China: a quantitative survey study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wei X, et al. Barriers to TB care for rural-to-urban migrant TB patients in Shanghai: a qualitative study. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2009;14:754–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang QL, et al. A study on the effects and affect factors of tuberculosis control in temporary residents of Shenzhen. Journal of Chinese Anti-tuberculosis Association. 2001;23:260–7. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li UF, et al. The effect of financial incentive mechanism on treatment compliance in migrant smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients groups. International Medicine and Health Guide News. 2011;17:1778–81. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cai FZ, et al. Implementation effect of fifth-round Global Fund tuberculosis project for floating population in Pudong New Area, Shanghai. Shanghai Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;6:266–8. [In Chinese] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nhlema B, et al. A systematic analysis of TB and poverty. Geneva: Stop TB Partnership, World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]