Abstract

Background:

Stigma is one of the obstacles in the treatment and regaining the mental health of people with mental illness. The aim was determination of mental illness stigma among nurses in psychiatric wards. This study was conducted in psychiatric wards of teaching hospitals in Tabriz, Urmia, and Ardabil in the north-west of Iran.

Materials and Methods:

This research is a descriptive analysis study in which 80 nurses participated. A researcher-made questionnaire was used, which measured demographic characteristics and mental illness stigma in the three components of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral. All data were analyzed using SPSS13 software and descriptive and analytical statistics.

Results:

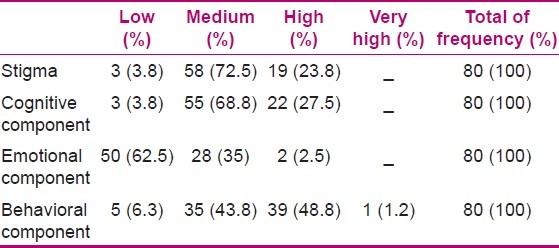

Majority of nurses (72.5%) had medium level of stigma toward people with mental illness. About half of them (48.8%) had great inclination toward the social isolation of patients. The majority of them (62.5%) had positive emotional responses and 27.5% had stereotypical views. There was a significant correlation between experience of living with and kinship of nurses to person with mental illness, with prejudice toward and discrimination of patients. There was also a significant correlation between interest in the continuation of work in the psychiatric ward and prejudice, and also between educational degree and stereotypical views.

Conclusions:

The data suggest there is a close correlation between the personal experience of nurses and existence of mental illness stigma among them. Therefore, the implementation of constant educational programs on mental illness for nurses and opportunities for them to have direct contact with treated patients is suggested.

Keywords: Attitude, Iran, mental disorders, nurses, social stigma

INTRODUCTION

Psychiatric patients not only suffer from mental illness, but also from its stigma. Guffman (1963) considers stigma as a deeply discrediting characteristic which reduces the bearer from a normal individual to an unstable and corrupt person.[1] According to social psychology models, stigma has three components of stereotypes (cognitive), prejudice (emotional), and discrimination (behavioral). Stereotypes are the knowledge structures learnt by most people within a society and are in fact representative of the general beliefs and consensus of people toward the characteristics of a certain group of that society. When a person believes in the stereotypes of a mental illness, he/she will have negative emotional reactions toward it, which shows social prejudice in the form of attitudes and values, and causes discrimination against and isolation of the patient, which places the person with mental illness in an unfavorable social situation.[2,3] Stigma causes the person with mental illness to face problems such as finding housing, employment,[4] access to judicial systems, and using health services, which cause isolation,[4] sense of shame,[5] and decrease psychosocial functions such as low self-esteem,[1] dissatisfaction with life, and mental health problems.[6] Moreover, stigma has a negative impact on the recovery process, treatment, seeking treatment, acceptance of psychological counseling,[7] and adherence to drug treatment.[8]

People with mental illness experience stigma from different sources such as society,[9,10] family, colleagues,[11] and mental healthcare practitioners.[12–16] Results of the study of Omidvari et al. (2008) on 1210 participants of 18-65 years old living in the 22 districts of Tehran showed that labeling, negative stereotyping, and a tendency toward social distance existed in most of the participants (66%), and that most of them have an average knowledge of mental illness.[10] It may be assumed that healthcare practitioners, because of having a university degree and direct contact to people with mental illness, will have little stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination; however, existing evidence gives controversial results. The study of Nordt et al. (2006), which compared the view of psychiatrics, mental health personnel, and ordinary people, showed that psychiatrics have more negative stereotypes than the general public, and that mental health personnel similar to the general public want to have social distance from people with mental illness. Moreover, they had a more positive attitude toward the compulsory hospitalization of patients in comparison to the public.[12] In a research in Nigeria, doctors believed the main cause of mental illnesses to be the misuse of drugs and alcohol. Around half of the doctors believed the cause of mental illnesses to be supernatural powers and people with mental illness to be dangerous, unpredictable, lacking self-control, and violent. The majority of them (61.4%) had high social distance from people with mental illness and believed prognosis to be weak.[13] In the research by Arvaniti et al. (2009), Nurses had the least favorable attitude toward people with mental illness, in comparison to doctors, medical students, and other healthcare personnel.[14] In another study, professional mental health groups were also less optimistic of prognosis compared to the general public and their view of the long-term results of the illness was less positive.[15] Stigma depends heavily on culture. Although according to Chambers et al., nurses had positive attitude toward people with mental illness, the attitudes of nurses in five different European countries were significantly different. The attitude of Portuguese nurses were the most positive and of the Lithuanian was the most negative.[16] In Iran, research has been conducted on the existence of stigma in the general public,[10] patient’s family,[17,18] and medical students;[19] however, no research was found on the healthcare personnel, especially nurses. Moreover, because of the influence of culture on stigma, existence of different results in different studies, and the negative impact of stigma on people with mental illness, it is essential that this topic be studied among nurses, the group of people who, because of their 24-h caring of patients, have the highest amount of interaction with them. Therefore, the goal of this study is to determine stigma, its components (stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination) and its correlation to demographical characteristics of nurses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research is a descriptive analysis study which was undertaken in a cross-sectional method in 2011. The study group consisted of 102 individuals composed of plan, contract, and formal nurses holding bachelor associate, bachelor, and higher degrees, and all licensed practical nurses working in psychiatric wards of Teaching Hospitals of Razi in Tabriz, psychiatry in Urmia, and Dr. Fatemi in Ardabil. Of this number, 8 because of not being eligible and 14 because of not completing the questionnaire were eliminated from the study, and 80 people who had at least 6 months of work experience in psychiatric wards and were interested in taking part in the study were included in the study. Therefore, because of the limitation in the number of nurses in these centers, the census sampling method was used.

For the purpose of data collection, a researchers-made questionnaire was used. This questionnaire consisted of two parts. Part one contained personal and social characteristics of nurses, which were: gender, age, marital status, educational degree, the university in which they graduated, duration of nursing service experience, duration of experience in psychiatric wards, employment status, place of work, working shift schedule, working in the ward according to personal interest, satisfaction of working in the ward, interest in continuing to work in the psychiatric ward, and past experience of living, having friendship, being neighbors, and/or family with a person with mental illness. Part two of the questionnaire consisted of measuring stigma, which was developed using a review of theoretical and empirical literature and the questionnaires of Community Attitudes toward the Mentally Ill, Attribution Questionnaire, and Perceived Devaluation Discrimination-General Public. This part consisted of 28 selection options which measured mental illness stigma in the three components of cognitive (stereotypes), emotional (prejudice), and behavioral (discrimination) using the six-point Likert Scale (strongly agree, agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree, with the lowest number 1 and the highest number 6). The cognitive component consisted of 16 selection options, the emotional component 4, and the behavioral component 8. To achieve content and face validity, the questionnaire was read by 10 faculty members of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and Tabriz University, and their feedback and suggestions of modifications were implemented in each one of the sentences. To determine its reliability, the questionnaire was filled by 20 of the eligible nurses and through Cronbach’s alpha coefficient its amount was calculated to be 0.74.

In this questionnaire, the range of stigma was 28-168. The range of 28-63 was considered to represent low stigma, 64-98 medium, 99-133 high, and 134-168 very high. In the stereotypes component 77-96 was low, 57-76 medium, 37-56 high, 16-36 very high; in the prejudice component 4-9 was low, 10-14 medium, 15-19 high, 20-24 very high; and in the discrimination component 8-18 was low, 19-28 medium, 29-38 high, and 39-48 very high. All data were analyzed using SPSS13 software. Descriptive statistics was used to show the frequency and frequency percentage of demographic characteristics and the intensity of stigma; the Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal Wallis H test were used in order to compare the difference in the rate of stigma according to demographic characteristics; and the Pearson correlation coefficient was used for the study of the correlation of the rate of stigma with age and years of past work experience. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

For data collection, the research permit was gained from the deputy of research of the medical universities of Tabriz, Urmia, and Ardabil. After gaining permission from the head of hospitals, the questionnaires were distributed among eligible nurses during working hours in psychiatric wards. They were collected after completion in the same working shift or the next. In this study, ethics needed in order to conduct research on human subjects were obeyed. The research project and its tools were approved by the regional research ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. All the participating nurses were informed of the study, its goals, and the rights of the participants to withdraw from the study. The confidentiality of data is considered and all participants according to the ethics committee rules gave an informed consent.

RESULTS

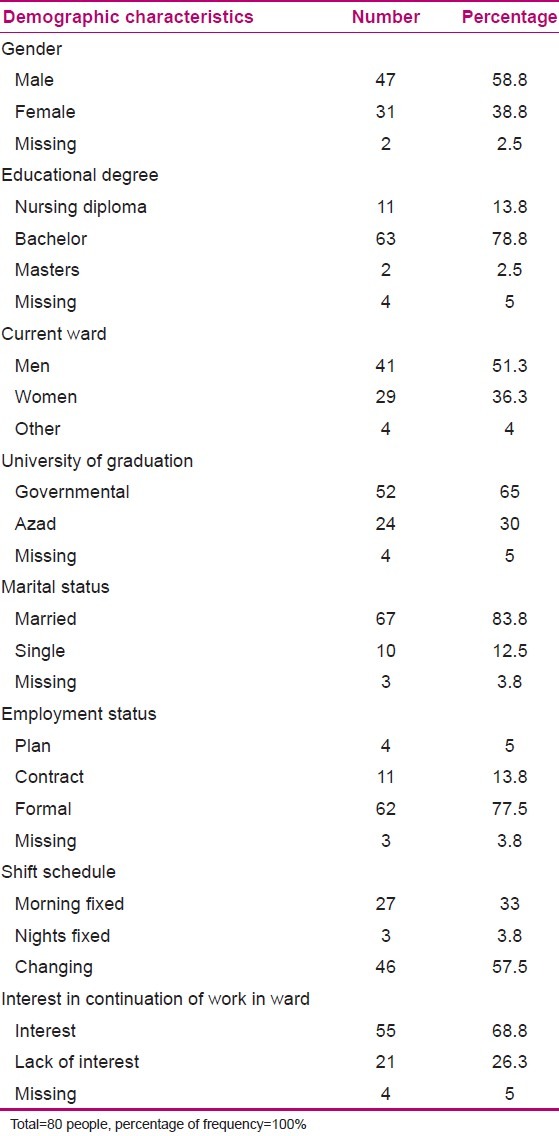

Samples of this study were 80 nurses and licensed practical nurses who had the average age of 37.3 with the standard deviation of 5.96, average years of nursing experience of 12.22 with standard deviation of 6.46, and average years of working experience in psychiatric wards 7.68 with standard deviation of 6.18. The majority of samples (60%) were working in psychiatric wards by their own choice and 70% were satisfied with their work in these wards. The majority of them (68.8%) wanted to continue working in the psychiatric wards and 8.8% had the experience of living, 17.5% having friendship, 18.8% being neighbors to, and 13.8% having family relations with at least one person with mental illness. Other demographic characteristics of participants have been listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

Among the participants in this study, the average total score of stigma was 87.95 with standard deviation of 13.36, the average score of the cognitive component (stereotyping) 51.28 with standard deviation of 8.68, the average score of emotional responses (prejudice) 8.49 with standard deviation of 2.65, and average score of behavioral responses 28.32 with standard deviation of 6.14. Table 2 illustrates the frequency and frequency percentage of participants according to ranking of the raw score of stigma and its three components in the four levels of low, medium, high, and very high.

Table 2.

Frequency and frequency percentage of people according to level of raw rate of stigma and its three components in four levels

According to the Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal Wallis H test, and the Pearson correlation coefficient, the findings of study show that age, gender, marital status, working shift schedule, employment type, working in the ward according to personal interest, and satisfaction with working in the ward had no meaningful relationship with stigma. However, the educational degree had a significant relation (P < 0.05) with cognitive component, and the university in which they graduated and willingness to continue working with the emotional component. Moreover, according to the Mann-Whitney U statistical test, the result showed that past experience of living with, and kinship to a person with mental illness had a significant relationship (P < 0.05) with the emotional and behavioral components of stigma.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study showed that mental illness stigma exists among nurses working in psychiatric wards of teaching hospitals in Tabriz, Urmia, and Ardabil. These results are inconsistent with the study results of Chambers et al. In the Chambers et al. study, the nurses had a positive attitude toward people with mental illness.[16] However, we must take into consideration that in their study there was a difference in the results for five different European countries; the attitudes of Portuguese nurses were the most positive and of the Lithuanian were the most negative. This could be due to issues such as the organization of services providing mental health services, and hospital facilities (for instance, the number of beds of a ward, nurse to patient ratio, and the combination of nurses of each shift according to sex and grade) which can affect the clinical work of nurses such as level of tension and violence among patients and the behavioral responses of nurses. These experiences in turn affect the nurses’ attitudes.

The results showed that 27.5% of nurses had high stereotypes about their patients. This was consistent with the results of the study of Adewuya and Oguntade.[13] In their research, Nigerian doctors had stereotypes about patients such as they are dangerous and unpredictable.

In the present study, the majority of nurses did not have the feeling of anger or fear toward people with mental illness, but instead were empathetic toward patients, and almost all of them wanted to help the mentally ill. Pankhurst (2009) states that the belief that the people with mental illness are responsible for their condition causes a feeling of anger toward them and the reduction of the assistance they can gain from others. On the contrary, the less responsibility attributed to the individual, the more pity and assistance they gain.[20] Considering that the majority of nurses in the present study did not see lack of personal discipline and willpower, and sinful behavior as the cause of mental illness, and the majority of them believed that patients are not responsible for their present condition, their positive emotional responses were predictable.

The majority of nurses wanted to apply social discrimination and restriction toward the patients, which was consistent with the results of other studies.[10,12,14] In the study of Omidvari, which was conducted on the ordinary citizens of Tehran, it was clear that the tendency for social distance from patients exists in majority of the participants (66%).[10] Considering the consistency of these results by the present study, and from the effects of social culture on the attitude of nurses, it can be concluded that stigma exists in all areas of people’s lives even at their place of work and that academic education has been unable to reduce the underlying stigmatizing attitudes.

Results of this study showed that people with the experience of living with or kinship to a person with mental illness had less prejudice against and discrimination of patients in comparison to other participants. In the study of Boyd et al. (2009), there was also a significant correlation between the personal contact with people with mental illness and less belief in isolation of patients and less feeling of anger and reproach.[21] In the study of Adewuya and Oguntade, Nigerian physicians with a relative who had a mental illness had less inclination toward social isolation of patients. In the study of Chin and Balon (2006), residents with a mentally ill relative had less stigmatizing attitudes.[22] The reason of nurses having a more negative emotional and behavioral response to patients could possibly be that they are mostly confronted with patients at an acute stage of their illness. It appears that knowledge of the symptoms associated with the acute phase of illness creates more stigma; on the contrary, knowledge about the aftercare sitting and social contact with patients can decrease the stigma.[23] In this study and that of Chin and Balon (2006), there was no significant correlation between having a friend or neighbor with mental illness and stigmatizing views.[22] It seems that only knowing an individual with a mental illness does not result in a decrease in stigma, but contact with people who have an experience of successful treatment is more affective in decreasing stigma. It can be concluded that creating opportunities for direct contact of nurses with hospitalized patients who now have a good-quality social life can decrease stigma. Boyd et al. (2009) stated that if people with mental illness who now have a good-quality social life announce the existence of their illness to their family and friends, and they can act as a stigma decreasing group within the society.[21]

It is clear that education can increase awareness and knowledge about mental health issues. Our study showed that bachelor and masters degree holders had fewer stereotypes (cognitive component) than licensed practical nurses. However, education alone is not effective in creating a positive view in those with underlying negative attitudes. The present study showed that three groups with different educational degrees do not have a statistically significant difference in emotional and behavioral components. Therefore, it seems that education along with personal and direct contact with successfully treated patients is effective in decreasing stigma toward mental illnesses.

Considering the results of the present study, it seems that revision and modification of mental health educational programs of nursing schools are necessary. Managers can provide in-service training programs for nurses to give them correct information on mental illnesses and help decrease the stereotypes among nurses. They can also make circumstances in which support communities for the psychiatric patients can be created, in which successfully treated patients can share their experiences with nurses, and in this way decrease and modify stereotypical patterns in nurses. Nurse managers can also, with the help of screening during the employing process, choose interested nurses with less feeling of stigma.

One of the limitations of this study was its general focus on mental illness. Participants may have answered the questionnaires with an imagination of a certain illness.

One other limitation of the study was that the participants completed the questionnaires themselves; therefore, they may have given answers which are more acceptable socially and according to their work ideology. Another limitation of the study was that it was conducted in mental wards at three health educational centers in the north-west of Iran, the results of which cannot be generalized to the whole society of working nurses in psychiatric wards in Iran.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the authorities, nurses, and licensed practical nurses of the Razi Psychiatric Hospital in Tabriz, Psychiatric Hospital of Urmia, and Dr. Fatemi Hospital in Ardabil, for their cooperation with us in this study. We would also like to thank the Research Vice chancellor of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for the financial support given to this research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This study was financially supported by the Research Vice chancellor of medical university of Tabriz

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crespo M, Perez-Santos E, Munoz M, Guillen AI. Descriptive study of stigma associated with severe and persistent mental illness among the general population of Madrid (Spain) Community Ment Health J. 2008;44:393–403. doi: 10.1007/s10597-008-9142-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corrigan PW, Kerr A, Knudsen L. The stigma of mental illness: Explanatory models and methods for change. Appl Prev Psychol. 2005;11:11179–90. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai YM, Hong CP, Chee CY. Stigma of mental illness. Singapore Med J. 2001;42:111–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray AJ. Stigma in psychiatry. J R Soc Med. 2002;95:72–6. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.95.2.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowitz FE. The effects of stigma on the psychological well-being and life satisfaction of persons with mental illness. J Health Soc Behav. 1998;39:335–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Givens JL, Katz IR, Bellamy S, Holmes WC. Stigma and the acceptability of depression treatments among African Americans and whites. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1292–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0276-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Alexopoulos GS, Perlick DA, Friedman SJ, Meyers BS. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: Perceived stigma and patient-rated severity of illness as predictors of antidepressant drug adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1615–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahl OF. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:467–78. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Omidvari S, Shahidzadeh Mahani A, Montazeri A, Baradaran HR, Azin A, Harerchee AM, et al. Tehran residents, knowledge and attitude regarding mental illnesses: A population based study. J Med Counc I.R Iran. 2007;26:278–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNutt C. MA Dissertation. Colorado, USA: University of the Rockies, School of Professional Psychology; 2010. The stigma of mental illness in the workplace; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordt C, Rossler W, Lauber C. Attitudes of mental health professionals toward people with schizophrenia and major depression. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:709–14. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adewuya AO, Oguntade AA. Doctors’ attitude towards people with mental illness in Western Nigeria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42:931–6. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arvaniti A, Samakouri M, Kalamara E, Bochtsou V, Bikos C, Livaditis M. Health service staff’s attitudes towards patients with mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:658–68. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0481-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hugo M. Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards people who have experienced a mental health disorder. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2001;8:419–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1351-0126.2001.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chambers M, Guise V, Valimaki M, Botelho MA, Scott A, Staniuliene V, et al. Nurses’ attitudes to mental illness: A comparison of a sample of nurses from five European countries. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:350–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadeghi M, Kaviani H, Rezai R. Stigma of mental disorder among families of patients with major depressive, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Adv Cogn Sci. 2003;5:16–25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shahveyis B, Shoja Shaftie S, Fadai F, Dolatshahi B. Comparison of mental illness stigmatization in families of with schizophrenic and major depressive disorder patients without psychotic features. J Rehabil. 2007;8:21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tavakoli S, Kaviani H, Sharifi V, Sadeghi M, Fotouhi A. Examination of cognitive, emotional and behavioral components of public stigma towards persons with mental illness. Adv Cogn Sci. 2006;8:31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pankhurst M. Doctor of psychology Thesis, Adler School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, USA. 2009. Attitudes of mental health professionals toward persons with chronic mental illness; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyd JE, Katz EP, Link BG, Phelan JC. The relationship of multiple aspects of stigma and personal contact with someone hospitalized for mental illness, in a nationally representative sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45:1063–70. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0147-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chin SH, Balon R. Attitudes and perceptions toward depression and schizophrenia among residents in different medical specialties. Acad Psychiatry. 2006;30:262–3. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.30.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llerena A, Caceres MC, Penas-LLedo EM. Schizophrenia stigma among medical and nursing undergraduates. Eur Psychiatry. 2002;17:298–9. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(02)00672-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]