Abstract

This study was designed to explore beneficial plant-associated rhizobacteria exhibiting substantial tolerance against fungicide tebuconazole vis-à-vis synthesizing plant growth regulators under fungicide stressed soils and to evaluate further these multifaceted rhizobacteria for protection and growth promotion of greengram [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek] plants against phytotoxicity of tebuconazole. Tebuconazole-tolerant and plant growth promoting bacterial strain PS1 was isolated from mustard (Brassica compestris) rhizosphere and identified as Pseudomonas aeruginosa following 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The P. aeruginosa strain PS1 solubilized phosphate significantly and produced indole acetic acid, siderophores, exo-polysaccharides, hydrogen cyanide and ammonia even under tebuconazole stress. Generally, tebuconazole at the recommended, two and three times the recommended field rate adversely affected the growth, symbiosis, grain yield and nutrient uptake in greengram in a concentration dependent manner. In contrast, the P. aeruginosa strain PS1 along with tebuconazole significantly, increased the growth parameters of the greengram plants. The inoculant strain PS1 increased appreciably root nitrogen, shoot nitrogen, root phosphorus, shoot phosphorus, and seed yield of greengram plants at all tested concentrations of tebuconazole when compared to the uninoculated plants treated with tebuconazole. The results suggested that the P. aeruginosa strain PS1, exhibiting novel plant growth regulating physiological features, can be applied as an eco-friendly and plant growth catalyzing bio-inoculant to ameliorate the performance of greengram in fungicide stressed soils.

Keywords: Legume, Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), Pseudomonas, Tebuconazole, Toxicity, Phosphate solubilization

1. Introduction

Rhizosphere microorganisms play a key role in biogeochemical cycling of elements and supply plants with the vital nutrients (Ahemad and Khan, 2011a). Bacteria of rhizosphere origin improving plant growth are generally, referred to as plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) (Zaidi et al., 2009). Among PGPR, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB) supply phosphorus (P) to plants by solubilizing insoluble P; principally through acidification process (Ahemad and Khan, 2012). In addition, PSB enhance the growth of plants by other mechanisms such as biological nitrogen fixation, providing trace elements (such as iron and zinc), synthesizing key plant growth promoting substances including siderophores and indole acetic acid (Tank and Saraf, 2003) and providing protection to plants against soil borne pathogens (El-Mehalawy, 2009). PSB without tolerance/resistance toward stress factors like fungicides in polluted soils would likely not facilitate the growth and yields of crops efficiently when used as bio-inoculants. To enhance the overall performance of crops in polluted environment including fungicide enriched soils, the bacterial cultures as inoculants must possess the potential to tolerate/detoxify pollutants including fungicide vis-à-vis the normal plant beneficial activities.

Prior to sowing, seed dressing with fungicides is regularly practiced in farming which sometimes fails to protect the seeds/plants against the intended pathogens or even suppress the production of secondary metabolites by plant-beneficial soil microbial communities (Yu et al., 2009; Ahemad and Khan, 2011a,b) besides impeding the overall productive efficiency of various crops including legumes (Fox et al., 2007). Tebuconazole [(RS)-1-p-chlorophenyl-4,4-dimethyl-3-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-ylmethyl) pentan-3-ol; CAS No. 107534-96] is a systemic and broad spectrum fungicide belonging to triazole group which is used widely as eradicant, and protectant to counterbalance phyto-pathogenic fungi (e.g. Curvularia spp., Fusarium spp., etc.) which cause powdery mildew, loose smut, and rust in both legume and non-legume crops (Kishorekumar et al., 2007; Singh and Dureja, 2009; Mohapatra et al., 2010). Mode of action of tebuconazole on fungal pathogens is to hamper the sterol biosynthesis leading to disruption in membrane formation (Tomlin, 1997). Despite its extensive use in pest control, the simultaneous effects of tebuconazole on PSB and greengram (Vigna radiata L. wilczek) are scarcely reported. The present study was therefore, directed to evaluate the possible impacts of tebuconazole on plant growth promoting (PGP) potentials of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PS1. The performance of the tebuconazole tolerant strain PS1 inoculated greengram [V. radiata (L.) Wilczek] plants was also assessed in tebuconazole treated alluvial soils.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Soil samples and microbial diversity

The soil samples were collected from the rhizospheric soils of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), lentil (Lens esculentus), greengram, pea (Pisum sativum) and mustard (Brassica compestris) grown at the experimental fields of Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh (27°29′ latitude and 72°29′ longitude), Uttar Pradesh, India. These agricultural fields were specifically selected to isolate the rhizobacteria because the selected sites were continuously exposed to a wide range of pesticides in crop production since 10 years. From each site, three soil samples were collected in sterilized polythene bags (15 × 12 cm2). The samples were mixed well and were used to determine microbial diversity including total bacterial population, fungal population and phosphate solubilizing microorganisms (PSM) using standard microbiological methods (Holt et al., 1994). The soil samples were serially diluted in sterile normal saline solutions and 10 μl of diluted suspension was spread plated on nutrient agar, Martin’s medium and Pikovskaya (Pikovskaya, 1948) medium for total bacterial count, fungal populations and phosphate solubilizers, respectively. Each sample was in three replicates and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 3, 5 and 7 days for total bacteria, fungi and phosphate solubilizing microorganisms, respectively.

2.2. Isolation of tebuconazole-tolerant and phosphate solubilizing bacteria

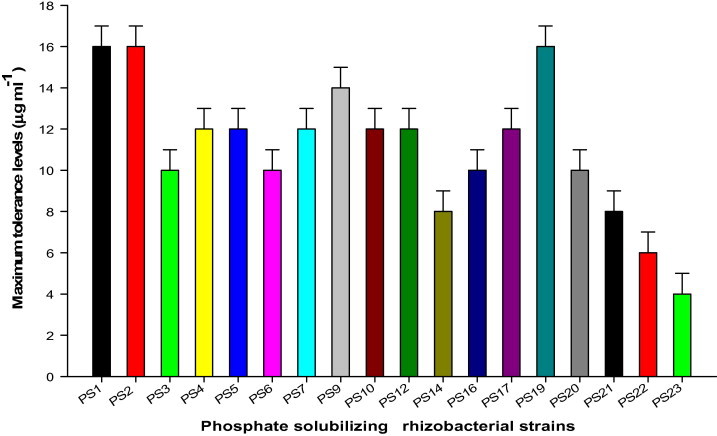

A total of 50 PSB were isolated from the rhizosphere of mustard (due to the maximum diversity of PSM) using soil dilution plate technique and tested for their phosphate-solubilizing activity (King, 1932). The sensitivity of bacterial strains against the increasing concentrations (100–3200 μg ml−1; at a dilution interval of 100 μg ml−1) of technical grade tebuconazole (a.i. 100% w/w; Parijat Agrochemicals, New Delhi, India) was evaluated by the plate assay using minimal salt agar medium (g/l: KH2PO4 1; K2HPO4 1; NH4NO3 1; MgSO4⋅7H2O 0.2; CaCl2⋅2H2O 0.02; FeSO4⋅7H2O 0.01; agar 15; pH 6.5). Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 7 days. The maximum concentration of tebuconazole supporting bacterial growth was defined as the maximum tolerance level (MTL). Subsequently, 18 bacterial strains: PS1, PS2, PS3, PS4, PS5, PS6, PS7, PS9, PS10, PS12, PS14, PS16, PS17, PS19, PS20, PS21, PS22 and PS23 endowed with the higher MTL (>400 μg ml−1) against tebuconazole were selected (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Maximum tolerance levels of phosphate solubilizing strains grown in minimal salt agar medium (devoid of carbon and nitrogen sources).

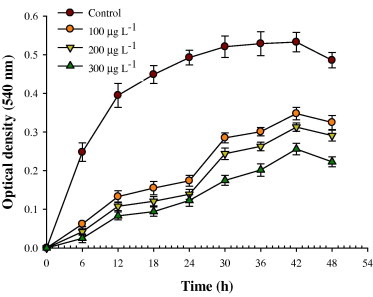

Exponentially grown cultures of the test organisms were inoculated into minimal salt medium treated with 0 (control), 100, 200, and 300 μg l−1 of tebuconazole and incubated at 30 °C in rotary shaker (150 g). Growth was determined turbidometrically at different time intervals by measuring optical density (OD) at 540 nm.

2.3. Assay of plant growth promoting traits

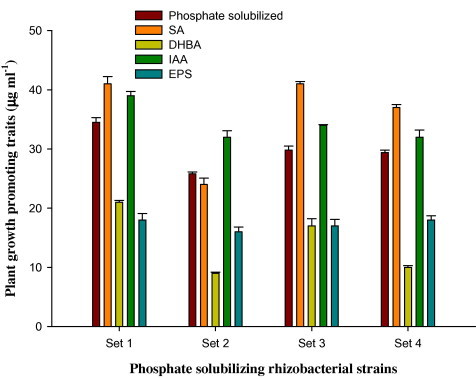

Bacterial strains were evaluated for phosphate solubilization, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), siderophores [salicylic acid (SA) and 2,3-dihydroxy benzoic acid (DHBA)], exo-polysaccharide (EPS), hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and ammonia both in the absence and the presence of tebuconazole 100 (recommended dose), 200 and 300 μg l−1. The various concentrations of tebuconazole used in experiments were corresponding to the field doses. Phytohormone, IAA was quantitatively analyzed by the method of Gordon and Weber (1951), later modified by Brick et al. (1991). The siderophore production by bacterial isolates was determined qualitatively using Chrome azurol S (CAS) agar (Alexander and Zuberer, 1991) as well as quantitatively (Reeves et al., 1983). The EPS and HCN produced by the rhizobacterial strains were determined by the method of Mody et al. (1989) and Bakker and Schipper (1987), respectively. The synthesis of ammonia by the bacterial strains was assayed using peptone water (Dye, 1962). Each individual experiment was repeated three times at different time intervals.

Out of 18 rhizobacterial strains, four bacterial strains (PS1, PS2, PS9 and PS19) producing the PGP substances in the highest amount and concurrently possessing greater values for MRL against tebuconazole were further selected (Fig. 2). Among these four rhizobacterial strains, the strain PS1 was selected to be used as a promising bio-inoculant owing to better growth in tebuconazole amended minimal salt agar medium (Fig. 3) and the comparatively higher production of PGP substances in vitro (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Plant growth promoting (PGP) activities of rhizobacterial strains recovered from mustard rhizosphere. Vertical bars represent mean of three replicates ± standard errors. Set 1, Set 2, Set 3 and Set 4 represent the PGP traits of the rhizobacterial strain PS1, PS2, PS9 and PS19, respectively. Salicylic acid; DHBA = 2,3-dihydroxy benzoic acid; IAA = indole acetic acid; EPS = exo-polysaccharides.

Figure 3.

Impact of the recommended, double and three times the recommended rate of tebuconazole on the P. aeruginosa strain PS1 (in terms of optical density) grown in minimal salt agar medium (devoid of carbon and nitrogen sources).

2.4. Bacterial characterization

Morphological, physiological and biochemical properties of the strain PS1, that included Gram reaction, citrate utilization test, indole production test, methyl red test, nitrate reduction, Voges Proskaur, catalase test, carbohydrates (dextrose, mannitol and sucrose) utilization test, starch hydrolysis, and gelatin liquefaction test, were determined as per the standard methods following Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology (Holt et al., 1994). On the basis of the above tests (Table 2), the strain PS1 was tentatively identified as Pseudomonas. The partial gene sequencing of 16S rRNA of the strain PS1 was performed commercially at DNA Sequencing Service, Macrogen Inc., Seoul, South Korea. Subsequently, nucleotide sequence data (Gen-Bank accession number FJ705886) was deposited in the Gen-Bank sequence database. The online program BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) was used to find out the related sequences with known taxonomic information in the databank at NCBI website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) to accurately identify the strain PS1. The BLAST program indicated that the strain PS1 shared a close relationship with the 16S rRNA gene sequence of P. aeruginosa strain MW3AC (99% similarity with the reference strain GQ180118) in NCBI database. Such high similar values confirmed the strain PS1 as P. aeruginosa.

Table 2.

Morphological and biochemical characteristics of the P. aeruginosa strain PS1.

| Characteristics | Strain PS1 |

|---|---|

| Morphology | |

| Gram reaction | − |

| Shape | Rods |

| Pigments | + |

| Biochemical reactions | |

| Citrate utilization | + |

| Indole | − |

| Methyl red | − |

| Nitrate reduction | + |

| Oxidase | + |

| Voges Proskaur | − |

| Carbohydrate utilization | |

| Glucose | + |

| Mannitol | − |

| Sucrose | + |

| Hydrolysis | |

| Starch | + |

| Gelatin | + |

| Tolerance to | |

| Tebuconazole | 1600 μg ml−1 |

‘+’ indicates positive and ‘−’ indicates negative reactions.

2.5. Plant growth under fungicide-stress

The experimental soil was an alluvial sandy clay loam (sand 667 g kg−1, silt 190 g kg−1, clay143 g kg−1, organic matter 6.2 g kg−1, Kjeldahl N 0.75 g kg−1, Olsen P 16 mg kg−1, pH 7.2 and WHC 0.44 ml g−1, cation exchange capacity 11.7 cmol kg−1 and 5.1 cmol kg−1 anion exchange capacity). Surface sterilized seeds of greengram var. K851 were bacterized with P. aeruginosa strain PS1 grown in LB broth by soaking the healthy seeds in liquid culture medium for 2 h using 10% gum arabic as sticker to deliver approximately 108 cells/seed. The un-inoculated but sterilized seeds were served as control. Inoculated and un-inoculated seeds were sown in clay pots (25 cm high, 22 cm internal diameter) containing 3 kg unsterilized soils with control (without tebuconazole) and three treatments with 100 [recommended field rate (1×)], 200 [two times the recommended field rate (2×)] and 300 μg kg−1 soil [three times the recommended field rate (3×)] of tebuconazole. A total of six pots arranged in a complete randomized design were included for each treatment. One week after emergence, plants were thinned to three per pot and maintained in open field conditions. The experiments were repeated for two consecutive years to establish the reproducibility of the results. All plants in three pots for each treatment were uprooted 50 and 80 days after seeding (DAS) and nodulation was recorded. Nodules were quantified, dried at 80 °C, and weighed. Plants removed at 50 and 80 DAS were oven-dried at (80 °C) and dry biomass was measured. The leghaemoglobin (Lb) content in fresh nodules collected from the roots of both inoculated and un-inoculated plants was measured at 50 DAS (Sadasivam and Manikam, 1992) while total N and P content in roots and shoots was assayed at 80 DAS by micro-Kjeldahl (Iswaran and Marwah, 1980) and Jackson (1967) method, respectively. The remaining pots (three pots) for each treatment having three plants per pot were maintained until harvest (80 DAS) and seed yield (SY) and grain protein (GP) (Sadasivam and Manikam, 1992) was determined.

2.6. Statistical analysis

In vitro experiments were carried out in three replicates at different time intervals. The difference among the treatment means was compared by honestly significant difference (HSD) using Tukey test at 5% probability level by statistical software SPPS10. The pot experiments were conducted for two consecutive years under similar environmental conditions using same treatments to ensure the reproducibility of the results. Since the data of the measured parameters obtained were homogenous, they were pooled together and subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA). The difference among treatment means was compared by two-way ANOVA at 5% level of probability using statistical software Mini-Tab11.

3. Results

3.1. Microbial diversity in different rhizospheric soils

The rhizospheric soils of chickpea, greengram, lentil, pea and mustard were subjected to microbial analysis. The viable counts of bacteria, fungi and PSM differed considerably among rhizosphere soils. Generally, the microbial populations were the highest in mustard rhizosphere compared to other soil samples. The bacterial populations in the rhizosphere of chickpea, greengram, lentil and pea were 3.2 × 107, 2.9 × 107, 3.5 × 107 and 3.1 × 107 CFU/g soil, respectively. In contrast, the rhizospheric soils of mustard exhibited 36%, 52%, 23% and 29% bacterial populations higher compared to those that recovered from chickpea, greengram, lentil, and pea rhizospheres, respectively. The fungal populations in the rhizospheric soils ranged from 1.2 × 105 (lentil) to 2.1 × 105 (greengram) CFU/g soil. Overall, the populations of PSB were comparatively higher than phosphate solubilizing fungi (PSF) in all soil samples. Among all the rhizosphere soils, the populations of PSB were the maximum in the rhizosphere of both chickpea and mustard and PSF counts were the highest in both pea and mustard rhizosphere. However, No PSF was recovered from chickpea rhizosphere. In general, mustard rhizosphere exhibited the highest PSM diversity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Microbial diversity in different soil samples collected from experimental fields of Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India.

| Sampling site | Microbial populations (colony forming units/g soil) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria (×105) | Fungi (×104) | Phosphate solubilizers (×105) |

||

| Bacteria | Fungi | |||

| Chickpea field | 321 | 13 | 6 | – |

| Greengram field | 286 | 21 | 2 | 0.2 |

| Lentil field | 353 | 12 | 3 | 0.2 |

| Pea field | 311 | 16 | 4 | 0.3 |

| Mustard field | 435 | 19 | 6 | 0.3 |

Each value is a mean of three independent replicates.

3.2. Fungicide-tolerance, characterization and plant growth promoting traits

In this study, a total of 50 rhizobacterial strains were isolated from the rhizopheric soils of mustard. Each rhizobacterial strain was tested for the tolerance level against tebuconazole on minimal salt agar medium. Of the 50 isolates, 18 rhizobacterial strains possessing higher tolerance against triazole fungicide were further selected (Fig. 1) and their plant growth promoting (PGP) traits were determined. Generally, the types and the amount of PGP substances were found to be higher for the rhizobacterial strain PS1, PS2, PS9 and PS19 (Fig. 2). Among the four strains, the P. aeruginosa strain PS1 was preferably selected due to its ability to (i) tolerate tebuconazole to the highest level up to 1600 μg ml−1 on minimal salt agar medium (Fig. 1), (ii) synthesize maximum amounts of plant growth promoting substances like IAA, siderophores, EPS, HCN and ammonia (Fig. 2), and (iii) grow well in minimal salts medium supplemented with tebuconazole at the recommended, two and three times of the recommended rate (Fig. 3). The tebuconazole-tolerant strain PS1 was further identified following biochemical tests (Table 2) and 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The strain PS1 produced a significant amount of PGP substances in the presence of the recommended, two and three times the recommended field rate of tebuconazole despite of tebuconazole-concentration dependent progressive decline in the production of PGP substances (except EPS) (Table 3). Interestingly, EPS production increased when the strain PS1 was exposed to tebuconazole stress. Consequently, the most promising P. aeruginosa strain PS1 was used as a promising bio-inoculant in pot trials.

Table 3.

Plant growth promoting activities of the P. aeruginosa strain PS1† both in the presence and absence of tebuconazole.

| Dose rate (μg l−1) | Phosphate solubilized (μg ml−1) | IAAa (μg ml−1) | Siderophores |

EPSe (μg ml−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASb agar (mm) |

Phenolates (μg ml−1) |

|||||

| SAc | 2,3-DHBAd | |||||

| 0 (control) | 345a | 39a | 15a | 41a | 21a | 18b |

| 100 | 93b | 9b | 14b | 27b | 8bc | 19b |

| 200 | 25c | 5c | 13b | 23c | 7c | 20b |

| 300 | 17d | 3d | 12c | 20 | 5d | 23a |

| F value | 148.5 | 101.4 | 68.4 | 115.7 | 228.3 | 63.5 |

Values indicate the mean of three replicates. Mean values followed by different letters are significantly different within a row or column at p ⩽ 0.05 according to Tukey test.

Indole acetic acid.

Chrome azurol s agar.

Salicylic acid.

2,3-Dihydroxy benzoic acid.

Exopolysaccharide.

P. aeruginosa strain PS1 also produced hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and ammonia at all three concentrations of tebuconzole.

3.3. Plant growth under fungicide-stress

The effect of three concentrations of tebuconazole including the recommended dose as well as tebuconazole-tolerant and plant growth promoting P. aeruginosa strain PS1 was assessed on the performance of greengram grown in tebuconazole-stressed sandy clay loam soils. When greengram plants were grown in soils amended with the three concentrations of tebuconazole, a considerable decline in measured growth parameters like plant dry biomass, nodulation, nutrient-uptake and yield was observed. The measured parameters decreased rather linearly as the concentration of tebuconazole was increased from 100 soil to 300 μg kg−1 soil irrespective of whether the inoculant (P. aeruginosa strain PS1) was used or not. However, the decline in plant growth parameters was proportionally low when strain PS1 was also used along with tebuconazole.

In the absence of bioinoculant, the toxicity of tebuconazole to greengram plants gradually increased with increasing concentration. For example, 100 μg kg−1 soil of tebuconazole significantly (p ⩽ .05) declined the root dry biomass by 17 and 21% at 50 and 80 DAS respectively while 300 μg kg−1 soil of tebuconazole at 50 and 80 DAS decreased the root dry biomass by 34% and 43%, respectively above the uninoculated control. Similarly, the sole application of 100 μg kg−1 soil tebuconazole, significantly (p ⩽ .05) decreased the shoot dry biomass by 26% and 36% at 50 DAS and 80 DAS, respectively whereas 300 μg kg−1 soil tebuconazole mediated reduction in the shoot dry biomass was found to be 40 (at 50 DAS) and 48%, (at 80 DAS), relative to the uninoculated control (Table 4). In contrast, bioinoculant PS1 in the presence of tebuconazole (300 μg kg−1 soil) significantly (p ⩽ .05) improved the dry matter accumulation in roots and shoots by 217 and 271%, respectively at 50 DAS and 307% and 535%, respectively at 80 DAS compared to uninoculated plants but treated with the same dose of tebuconazole (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of three concentrations of tebuconazole on growth and symbiotic properties of greengram plants grown in soil inoculated with the P. aeruginosa strain PS1 and without bio-inoculant.

| Treatments | Dose rate (μg kg−1 soil) | Dry biomass (g plant−1) |

Nodulation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root |

Shoot |

No. plant−1 |

Dry biomass (mg plant−1) |

||||||

| 50 DAS | 80 DAS | 50 DAS | 80 DAS | 50 DAS | 80 DAS | 50 DAS | 80 DAS | ||

| Un-inoculated | Control | 0.35 | 0.47 | 1.59 | 2.08 | 21 | 17 | 66 | 52 |

| 100 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 1.18 | 1.34 | 16 | 13 | 50 | 44 | |

| 200 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 1.06 | 1.20 | 12 | 9 | 44 | 38 | |

| 300 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.95 | 1.08 | 10 | 8 | 40 | 32 | |

| Inoculated | Control | 1.76 | 2.56 | 8.70 | 11.66 | 41 | 36 | 399 | 316 |

| 100 | 1.03 | 1.50 | 6.86 | 8.53 | 28 | 25 | 152 | 125 | |

| 200 | 0.83 | 1.40 | 4.46 | 7.70 | 28 | 22 | 137 | 110 | |

| 300 | 0.73 | 1.10 | 3.53 | 6.86 | 27 | 16 | 128 | 83 | |

| LSD | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.4 | |

| F value | Inoculation(df = 1) | 2288⁎ | 451⁎ | 1028⁎ | 2460⁎ | 252⁎ | 1027⁎ | 93.4⁎ | 258⁎ |

| Fungicide (df = 3) | 421⁎ | 95.2⁎ | 272⁎ | 423⁎ | 28⁎ | 63⁎ | 7.7⁎ | 29.0⁎ | |

| Inoculation × fungicide (df = 3) | 502⁎ | 86.3⁎ | 276⁎ | 392⁎ | 18.6⁎ | 73⁎ | 6.6⁎ | 20.8⁎ | |

Values are mean of three replicates where each replicate constituted three plants pot−1.

Significantly different from the control at p ⩽ 0.05.

Moreover, 100 μg kg−1 soil of tebuconazole decreased the nodule numbers by 24% at both 50 DAS and 80 DAS while nodule biomass declined by 25% and 15% at 50 DAS and 80 DAS, respectively. In contrast, 300 μg kg−1 soil of tebuconazole decreased the nodule numbers and their dry mass by 52% and 49% respectively, at 50 DAS and by 53% and 38% respectively, at 80 DAS compared to control. Despite tebuconazole mediated deleterious effects on symbiosis, bioinoculant strain PS1 relatively ameliorated the symbiotic attributes of greengram plants for all concentrations of fungicide when strain PS1 inoculated and uninoculated greengram plants exposed to the same concentrations of fungicide were compared. For example, increment in nodule numbers and nodule dry mass was observed by 170% and 220%, respectively at 50 DAS and 100% and 159%, respectively at 80 DAS respectively, while comparing the effect of 300 μg/kg soil tebuconazole treated uninoculated and inoculated plants (Table 4).

Generally, tebuconazole declined the chlorophyll content marginally both in the presence or absence of bioinoculant. In the absence of bioinoculant, 12% and 50% decline in Lb content was observed at 100 and 300 μg kg−1 soil of tebuconazole, respectively compared to uninoculated control. Interestingly, bioinoculant PS1 increased the Lb content in nodules significantly (p ⩽ .05) by 25% in the presence of 300 μg kg−1 soil of tebuconazole when compared to the uninoculated treatment having the same concentration of tebuconazole (Table 5). Furthermore, N and P content, SY and GP decreased progressively with increase in the dose rate of tebuconazole (Table 5) either in the presence or the absence of PS1 strain. Grain protein was however, marginally affected. For instance, the percent reduction in root N, shoot N, root P, shoot P, and SY of greengram at 100 μg kg−1 soil of tebuconazole was 19, 18, 22, 20 and 35, respectively while the decrease in percent was 25, 30, 37, 33 and 49 for root N, shoot N, root P, shoot P, and SY, respectively at 300 μg kg−1 soil of tebuconazole, compared to the control. In contrast, the inoculant strain significantly (p ⩽ 0.05) increased the root N, shoot N, root P, shoot P, SY and GP at all concentrations of fungicide compared to the sole application of fungicide. For example, the inoculant when used with fungicide, increased the same parameters by 7%, 28%, 23%, 46%, 105% and 2%, respectively, at 300 μg kg−1 soil of tebuconazole when compared with only fungicide treated soils (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of three concentrations of tebuconazole on biological and chemical properties of greengram plants grown in soil inoculated with the P. aeruginosa strain PS1 and without bio-inoculant.

| Treatments | Dose rate (μg kg−1 soil) | Leghaemoglobin content [mM (g f.m.)−1] | Chlorophyll content (mg g−1) | N content (mg g−1) |

P content (mg g−1) |

Seed yield (g plant−1) | Seed protein (mg g−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root | Shoot | Root | Shoot | ||||||

| Un-inoculated | Control | 0.08 | 0.82 | 36 | 50 | 0.27 | 0.36 | 7.4 | 261 |

| 100 | 0.07 | 0.75 | 29 | 41 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 4.8 | 246 | |

| 200 | 0.05 | 0.72 | 25 | 37 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 4.3 | 244 | |

| 300 | 0.04 | 0.70 | 27 | 35 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 3.8 | 241 | |

| Inoculated | Control | 0.09 | 0.96 | 48 | 69 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 12.7 | 272 |

| 100 | 0.08 | 0.84 | 36 | 56 | 0.30 | 0.39 | 9.2 | 257 | |

| 200 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 31 | 51 | 0.26 | 0.37 | 8.5 | 250 | |

| 300 | 0.05 | 0.75 | 29 | 45 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 7.8 | 246 | |

| LSD | 0.005 | 0.04 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.3 | 2.5 | |

| F value | Inoculation (df = 1) | 326⁎ | 7.2⁎ | 363⁎ | 47.3⁎ | 771.7⁎ | 1155⁎ | 265.5⁎ | 19⁎ |

| Fungicide (df = 3) | 8.7⁎ | 1.1 | 201.9⁎ | 35.1⁎ | 347.7⁎ | 74.7⁎ | 32.7⁎ | 11⁎ | |

| Inoculation × fungicide (df = 3) | 31.5⁎ | 0.4 | 50.1⁎ | 14.5⁎ | 76.4⁎ | 119.5⁎ | 20.9⁎ | 3.5⁎ | |

Values are mean of three replicates where each replicate constituted three plants pot−1.

Significantly different from the control at p ⩽ 0.05; (g.f.m.)−1 = (gram fresh biomass)−1.

Moreover, the two-factor ANOVA revealed that the individual effects of inoculation and fungicide and their interactive effect (inoculation × fungicide) were significant (p ⩽ 0.05) for all plant growth parameters except the effect of fungicide and its interaction with inoculant PS1 for chlorophyll content (Tables 4 and 5).

4. Discussion

4.1. Microbial diversity of rhizospheric soils

Microbial communities of soils play pivotal roles in various biogeochemical cycles and influence the fertility of soils. In addition, soil microflora influence above-ground ecosystems by providing nutrients to plants; improve soil structures and consequently, affect soil health (Ahemad et al., 2009). Such microbes are also involved in many other soil processes e.g. decomposition of organic matter, nutrient mobilization and mineralization, mineral phosphate solubilization, denitrification, bioremediation of pollutants and suppression of soil borne phytopathogens (Rameshkumar and Nair, 2009; Khan et al., 2010; Ahemad and khan, 2011c). Furthermore, microbial diversity varies greatly from soil to soil or plant genotype to genotype. In the present study, viable counts of diverse microbial communities including phosphate solubilizers and fungal populations inhabiting rhizospheric soils of different plants were determined. A significant variation in microbial diversity in rhizospheric soils of legume (pea, chickpea, lentil and greengram) and non-legume (mustard) crops was observed. Generally, PSM population was the high in the soil samples collected from mustard rhizosphere compared to legume rhizospheres; the minimum microbial count was however, recorded in greengram rhizosphere. The variation in heterogeneous microbial populations in tested rhizospheric soils may probably be attributed to the changes in physico-chemical properties (such as, pH, temperature, moisture content, organic matter content) of tested soils (Ahemad et al., 2009) or due to difference in the concentration and types of nutrients exuded by different plant species (Zaidi et al., 2009).

4.2. Effect of fungicide on greengram growth

The application of tebuconazole at all doses tested in this study showed a significant (p ⩽ 0.05) phytotoxicity to greengram plants and severely affected the dry matter accumulation, nitrogen fixing determinants: nodule numbers, nodule dry biomass and Lb, nutrient-uptake, and yield and quality of grains. The doses of fungicide higher than the recommended one had displayed more toxicity to greengram plants. The reduction in of greengram growth following fungicide application in this study, could be due to the adverse effects of tebuconazole on N2-fixation (owing to the disruption of signaling between phytochemicals and Rhizobium Nod D receptors) (Fox et al., 2007) or viability/activity of PGPR (Guene et al., 2003) or as a result of inhibition of enzymes involved in growth and metabolisms of plants (Zablotowicz and Reddy, 2004). Moreover, our study also showed that the toxic effect of two and three times the recommended dose of tebuconazole to the greengram plants was more severe than that of the recommended dose. Fungicides at lower rates are generally not toxic possibly because of the buffering nature of soils these chemicals become diluted (Ayansina, 2009).

4.3. P. aeruginosa PS1-mediated growth promotion and protection against fungicide

Interestingly, the measured parameters were increased following inoculant (the P. aeruginosa strain PS1) application with tebuconazole compared to plants grown in soils treated solely with tebuconazole. This increment in growth parameters may be attributed either to the detoxification of fungicides by the strain PS1 (Yang and Lee, 2008) or secretion of the plant growth regulating substances in rhizosphere (Zaidi et al., 2009). The fungicide-detoxifying potential of the strain PS1 is also supported by the luxurious growth of this strain on minimal media having tebuconazole as only C and N source (Fig. 3). Moreover, the introduced agrochemical may be a new source of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur which if utilized by one microbial community allows them to proliferate and out-compete other microbial communities (Ayansina, 2009). Hence, this trait confers the selective advantage to the strain PS1 in greengram rhizosphere to alienate other soil microflora. Consequently, the strain PS1 not only protected the greengram plants from fungicide toxicity but also increased the growth and symbiotic attributes of the test plants substantially in fungicide-amended soils.

The strain PS1 produced EPS substantially even in the presence of tested fungicide (Table 3). EPS is believed to play an important role in attachment of bacterial cells to varied surfaces, osmoregulation and ion transport (Spaink, 2000). These EPS might have masked the toxic effects of tebuconazole by forming a polymeric network around this fungicide, and hence, prevented the uptake of fungicide by growing plants. It has also been reported earlier that EPS influence legume root infection and nodulation (Leigh et al., 1988; Parveen et al., 1997; Muthomi et al., 2007). In this study, the N content in plant organs (root and shoot) was therefore, also higher in inoculated plants (Table 5) probably due to increased N2 fixation which led to a considerable increase in N uptake (Joshi et al., 1990). Further, the phosphate solubilizing P. aeruginosa strain PS1 showed remarkable phosphate solubilizing potency until three times the recommended dose of tebuconazole in vitro conditions (Table 3). It is possible that the inoculant PS1 supplied the available forms of phosphorus to greengram plants in surplus amount. Therefore, the P content significantly increased in the strain PS1-inoculated plants compared to the uninoculated ones. The increased P uptake in plants in response to PSB inoculation is well reported (Zaidi et al., 2009; Ahemad and Khan, 2011d). As well, the synthesis of siderophores and IAA by the test strain PS1 might also have induced root growth and uptake of soil minerals by the host plants.

5. Conclusions

Tebuconazole-tolerant P. aeruginosa strain PS1 as seed inoculant not only shielded the greengram plants from the phytotoxicity of tebuconazole but also increased the overall growth of greengram plants. The increased growth of inoculated greengram plants even in the presence of fungicide, in this study, might have possibly been due to the synthesis and release of plant growth promoting substances like IAA, siderophores and EPS by the P. aeruginosa strain PS1 in addition to its intrinsic ability of mineral phosphate solubilization. This study inferred that the P. aeruginosa strain PS1 with multiple PGP traits can be used as bio-inoculant to increase the productivity of legumes in fungicide contaminated soils.

Acknowledgments

The authors express gratitude to Dr. N. A. Naqvi, Parijat Agrochemicals, New Delhi, India, for providing technical grade tebuconazole. Financial assistance from the University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi, INDIA is thankfully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

Munees Ahemad, Email: muneesmicro@rediffmail.com.

Mohammad Saghir Khan, Email: khanms17@rediffmail.com.

References

- Ahemad M., Khan M.S. Effect of fungicides on plant growth promoting activities of phosphate solubilizing Pseudomonas putida isolated from mustard (Brassica compestris) rhizosphere. Chemosphere. 2012;86:945–950. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahemad M., Khan M.S. Ecotoxicological assessment of pesticides towards the plant growth promoting activities of lentil (Lens esculentus)-specific Rhizobium spp. strain MRL3. Ecotoxicology. 2011;20:661–669. doi: 10.1007/s10646-011-0606-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahemad M., Khan M.S. Effect of pesticides on plant growth promoting traits of greengram-symbiont, Bradyrhizobium spp. strain MRM6. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011;86:384–388. doi: 10.1007/s00128-011-0231-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahemad M., Khan M.S. Pesticide interactions with soil microflora: importance in bioremediation. In: Ahmad I., Ahmad F., Pichtel J., editors. Microbes and Microbial Technology: Agricultural and Environmental Applications. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 393–413. [Google Scholar]

- Ahemad M., Khan M.S. Functional aspects of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria: recent advancements. Insight Microbiol. 2011;1:39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ahemad M., Zaidi A., Khan M.S., Oves M. Factors affecting the variation of microbial communities in different agro-ecosystems. In: Khan M.S., Zaidi A., Musarrat J., editors. Microbial Strategies for Crop Improvement. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2009. pp. 301–324. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander D.B., Zuberer D.A. Use of chrome azurol S reagents to evaluate siderophore production by rhizosphere bacteria. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 1991;12:39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ayansina A.D.V. Pesticide use in agriculture and microorganisms. In: Khan M.S., Zaidi A., Musarrat J., editors. Microbes in Sustainable Agriculture. Nova Science Publishers Inc.; New York: 2009. pp. 261–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.W., Schipper B. Microbial cyanide production in the rhizosphere in relation to potato yield reduction and Pseudomonas spp. mediated plant growth stimulation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987;19:451–457. [Google Scholar]

- Brick J.M., Bostock R.M., Silversone S.E. Rapid in situ assay for indole acetic acid production by bacteria immobilized on nitrocellulose membrane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991;57:535–538. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.535-538.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dye D.W. The inadequacy of the usual determinative tests for the identification of Xanthomonas spp. Nat. Sci. 1962;5:393–416. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mehalawy A.A. Management of plant diseases using phosphate-solubilizing microbes. In: Khan M.S., Zaidi A., editors. Phosphate Solubilizing Microbes for Crop Improvement. Nova Science Publishers Inc.; USA: 2009. pp. 265–279. [Google Scholar]

- Fox J.E., Gulledge J., Engelhaupt E., Burow M.E., McLachlan J.A. Pesticides reduce symbiotic efficiency of nitrogen-fixing rhizobia and host plants. PNAS. 2007;104:10282–10287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon S., Weber R.P. The colorimetric estimation of IAA. Plant Physiol. 1951;26:192–195. doi: 10.1104/pp.26.1.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guene N.F.D., Diouf A., Gueye M. Nodulation and nitrogen fixation of field grown common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) as influenced by fungicide seed treatment. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2003;2:198–201. [Google Scholar]

- Holt J.G., Krieg N.R., Sneath P.H.A., Staley J.T., Willams S.T. 9th ed. Williams and Wilkins; USA: 1994. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. [Google Scholar]

- Iswaran V., Marwah T.S. A modified rapid Kjeldahl method for determination of total nitrogen in agricultural and biological materials. Geobios. 1980;7:281–282. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson M.L. Prentice-Hall of India; New Delhi: 1967. Soil Chemical Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi P.K., Kulkarni J.H., Bhatt D.M. Interaction between strains of Bradyrhizobium and groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) cultivars. Tropic. Agric. 1990;67:115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.S., Zaidi A., Ahemad M., Oves M., Wani P.A. Plant growth promotion by phosphate solubilizing fungi – current perspective. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2010;56:73–98. [Google Scholar]

- King J.E. The colorimetric determination of phosphorus. Biochem. J. 1932;26:292–295. doi: 10.1042/bj0260292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishorekumar A., Abdul Jaleel C., Manivannan P., Sankar B., Sridharan R., Panneerselvam R. Comparative effects of different triazole compounds on growth, photosynthetic pigments and carbohydrate metabolism of Solenostemon rotundifolius. Colloid Surface B. 2007;60:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh J.A., Singer E.R., Walker G.C. Exopolysaccharide deficient mutants of Rhizobium meliloti that form ineffective nodules. PNAS. 1988;82:6231–6235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody B.R., Bindra M.O., Modi V.V. Extracellular polysaccharides of cowpea rhizobia: compositional and functional studies. Arch. Microbiol. 1989;1:2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra S., Ahuja A.K., Deepa M., Jagadish G.K., Prakash G.S., Kumar S. Behaviour of trifloxystrobin and tebuconazole on grapes under semi-arid tropical climatic conditions. Pest Manage. Sci. 2010;66:910–915. doi: 10.1002/ps.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthomi J.W., Otieno P.E., Cheminingwa G.N., Nderitu J.H., Wagacha J.M. Effect of legume root rot pathogens and fungicide seed treatment on nodulation and biomass accumulation. J. Biol. Sci. 2007;7:1163–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Parveen N., Webb D.T., Borthakur D. The symbiotic phenotypes of exopolysaccharide-defective mutants of Rhizobium spp. strain TAL1145 do not differ on determinate – and indeterminate-nodulating tree legumes. Microbiology. 1997;143:1959–1967. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pikovskaya R.I. Mobilization of phosphorus in soil in connection with vital activity of some microbial species. Microbiology. 1948;17:362–370. [Google Scholar]

- Rameshkumar N., Nair S. Isolation and molecular characterization of genetically diverse antagonistic, diazotrophic red-pigmented vibrios from different mangrove rhizospheres. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2009;67:455–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves M.W., Pine L., Neilands J.B., Balows A. Absence of siderophore activity in Legionella species grown in iron-deficient media. J. Bacteriol. 1983;154:324–329. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.324-329.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadasivam S., Manikam A. Wiley Eastern Limited; New Delhi: 1992. Biochemical Methods for Agricultural Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Dureja P. Effect of biocompost-amendment on degradation of triazoles fungicides in soil. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009;82:120–123. doi: 10.1007/s00128-008-9536-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaink H.P. Root nodulation and infection factors produced by rhizobial bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000;54:257–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tank N., Saraf M. Phosphate solubilization, exopolysaccharide production and indole acetic acid secretion by rhizobacteria isolated from Trigonella foenum-graecum. Indian J. Microbiol. 2003;43:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlin C.D.S. The British Crop Protection Council; Surrey, UK: 1997. The Pesticide Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Lee C. Enrichment, isolation, and characterization of 4-chlorophenol-degrading bacterium Rhizobium spp. 4-CP-20. Biodegradation. 2008;19:329–336. doi: 10.1007/s10532-007-9139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Chu X., Pang G., Xiang Y., Fang H. Effects of repeated applications of fungicide carbendazim on its persistence and microbial community in soil. J. Environ. Sci. 2009;21:179–185. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(08)62248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zablotowicz R.M., Reddy K.N. Impact of glyphosate on the Bradyrhizobium japonicum symbiosis with glyphosate-resistant transgenic soybean: a mini review. J. Environ. Quality. 2004;33:825–831. doi: 10.2134/jeq2004.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi A., Khan M.S., Ahemad M., Oves M. Plant growth promotion by phosphate solubilizing bacteria. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2009;56:263–284. doi: 10.1556/AMicr.56.2009.3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]