Abstract

Objective

To describe a disaster recovery model focused on developing mental health services and capacity-building within a disparities-focused, community-academic participatory partnership framework.

Design

Community-based participatory, partnered training and services delivery intervention in a post-disaster setting.

Setting

Post-Katrina Greater New Orleans community.

Participants

More than 400 community providers from more than 70 health and social services agencies participated in the trainings.

Intervention

Partnered development of a training and services delivery program involving physicians, therapists, community health workers, and other clinical and non-clinical personnel to improve access and quality of care for mental health services in a post-disaster setting.

Main outcome measure

Services delivery (outreach, education, screening, referral, direct treatment); training delivery; satisfaction and feedback related to training; partnered development of training products.

Results

Clinical services in the form of outreach, education, screening, referral and treatment were provided in excess of 110,000 service units. More than 400 trainees participated in training, and provided feedback that led to evolution of training curricula and training products, to meet evolving community needs over time. Participant satisfaction with training generally scored very highly.

Conclusion

This paper describes a participatory, health-focused model of community recovery that began with addressing emerging, unmet mental health needs using a disparities-conscious partnership framework as one of the principle mechanisms for intervention. Population mental health needs were addressed by investment in infrastructure and services capacity among small and medium sized non-profit organizations working in disaster-impacted, low resource settings.

Keywords: Community-based Participatory Research, Collaborative Care, Disaster, Mental Health

Introduction

The disasters of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita contributed to unmet need for mental health services among the affected population, approximately one third of whom experienced symptoms of depression, post traumatic stress or anxiety.1–3 Mental health services responses in New Orleans were hampered by limited baseline services capacity prior to the disaster and stigma.4 Displacement of specialty providers –only 22 psychiatrists practiced in the Greater New Orleans area nearly one year after the storms5 as well as infrastructure damage resulting in closure of health facilities, including New Orleans’ only public hospital, further stymied community access to evidence-based mental health services.

Community disaster recovery may be limited or slowed when significant proportions of the population are affected or disabled by cognitive impairment associated depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder. Racial and ethnic minority communities may be at greatest risk of delayed recovery, given the higher burden of disaster impact experienced6 and their lower likelihood of receiving appropriate mental health care.7–10

Community-academic partnered approaches in training, research, and services delivery may improve population mental health and resilience, and may offer certain advantages following a major disaster, particularly in low resource settings and among racial and ethnic minority groups.4,11,12 In a partnered, community participatory approach, academicians may facilitate training and uptake of evidence-based models by community providers, while community members contribute invaluable insight into how to tailor these models to improve implementation based on their intimate understanding of community need, expectations, and contextual factors.13–15 Together community members and academics may set the stage for impactful population-level interventions and innovative, equitable research agendas and information exchange.8

REACH NOLA is a 501c3 nonprofit organization based in New Orleans, the mission of which is to improve health equity, community health, and access to quality health care through partnered programs, services, and research.16 REACH NOLA began in April 2006 as a novel, community-academic collaborative that organized to address post-Katrina health needs in New Orleans by uniting the unique strengths of community agencies and academic institutions. REACH NOLA partners applied an equity-focused framework drawing from principles and practices of community-based participatory research (CBPR)12,17,18 to conduct a rapid community-participatory assessment of access to health care in post-Katrina New Orleans. The partners shared the findings from this assessment with community members, policymakers, and health agency leaders as a basis for planning partnered responses to the community health challenges that subsequently were identified.4,19

In recognition of the epidemic of unmet post-disaster mental health needs, REACH NOLA’s lead community partners (St. Anna Medical Mission, Holy Cross Neighborhood Association, Common Ground Health Clinic, Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana, St. Thomas Community Health Center and others), as well as REACH NOLA’s lead academic partners, (RAND Health, the UCLA Health Services Research Center, the Tulane University School of Tulane School of Medicine Section of General Internal Medicine and Geriatrics) developed proposals to work together to meet post-disaster community mental health challenges. As recovery proceeded, community and academic partners agreed that there was a broader need to support competencies for mental health recovery, following community priorities, and relying to the extent feasible on evidence-based approaches, to support improved outcomes in mental health. The nascent REACH NOLA partnership garnered critical initial support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and later from the hurricane recovery program of the American Red Cross, to work to improve access to and quality of post-hurricane mental health services in the greater New Orleans region. Partner agencies developed two health and resilience centers featuring collaborative pilot programs through the St. Anna Episcopal Church Medical Mission and the Tulane Community Health Center at Covenant House. These centers and their partners together built capacity for high quality mental health services delivery, and provision of social services in accessible, neighborhood settings.20

This article describes the next phase of this trajectory of development; the REACH NOLA Mental Health Infrastructure and Training (MHIT) Project. It is, to our knowledge, the first peer-reviewed account of disaster recovery model specifically focused on developing mental health services and building capacity for agencies and providers within a disparities-focused, community-academic participatory partnership framework. This descriptive overview provides insight into development of MHIT’s programmatic structures and products and their application in Greater New Orleans after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita to improve mental health.

Methods

This narrative history of the REACH NOLA MHIT is drawn from project documents including meeting minutes, training agendas, participant surveys, project web pages, service reports, and recollections from key participants. Building on the initial progress of its health and resilience centers, beginning in 2008, REACH NOLA developed MHIT as a broader capacity-development initiative. The intent of MHIT was to support development of accessible, high-quality mental health services among health and social service agencies that work with underserved populations in Greater New Orleans, while supporting growth of community leadership to address disparities in mental health care and to advance disaster recovery. The mechanisms to accomplish this intent included: 1) using community-participatory methods to develop and deliver work-force training programs for evidence-based therapies for depression and trauma, based on versions of collaborative care and other models; 21–23 2) providing financial support to agencies to hire needed staff; and 3) building novel linkages within and among clinical and non-clinical agencies and providers to integrate services into a wider range of neighborhood-based primary care and social services settings, particularly through community health workers, therapists, and primary care providers. 13–15,24

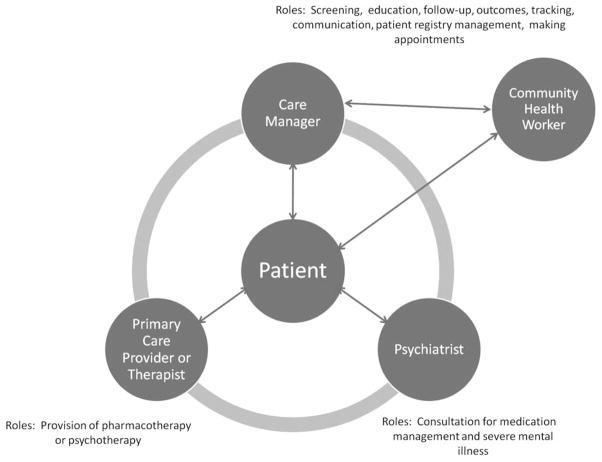

Use of community participatory methods has been advanced for its value in improving mental health services capacity to support public health, including after disasters.11,12,25 The MHIT adhered to major tenets of community participatory work including shared power and financial resources, community and academic involvement in all aspects of the project, and mutual respect for all participants’ contributions.11 Project leaders established a project council to create a structure for equitable participation in project development and execution. Comprising multiple community and academic agency partners (Table 1) representing a range of relevant experiences and strengths,26 the council used consensus decision making to guide the project. During weekly conference calls, as well as ad hoc and committee meetings, the council identified options for implementing programs using evidence-based services in community settings. Academic partners lent experience in collaborative care for depression21,22 (Figure 1) and cognitive behavioral therapy.27,28 Community partners lent substantial expertise in recovery leadership, and conducting community sensitive outreach, education, and referrals among disaster-impacted communities.

Table 1.

Project council partner agencies

| Agency | Agency type | Areas of expertise | Role in project council |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Ground Health Clinic commongroundclinic.org/ | Community-based health care provider | Health care delivery Community outreach, engagement, organizing, and context |

Supported proposal development Provided mental health services Co-led training sessions Provided feedback on training curricula |

| Episcopal Community Services (ECSLA) ecsla.org/ | Community-based social service provider | Case management Community outreach, engagement, and context |

Supported proposal development Provided mental health services Provided feedback on training curricula |

| Holy Cross Neighborhood Association helpholycross.org/ | Community-based organization | Community outreach, engagement, and context | Supported proposal development Provided mental health outreach, education, screening, and referrals Co-led training sessions Co-developed training curricula Disseminated project results |

| RAND Health rand.org/health.html | Policy research institution | Project direction and development Evidence-based mental health care models |

Supported proposal development Co-led training sessions Co-developed training curricula Supported project direction Provided model implementation support Disseminated project results |

| St. Anna’s Medical Mission stannanola.org/samm.php | Community-based health care provider | Health care delivery Community outreach, engagement, and context |

Supported proposal development Provided mental health services Co-led training sessions Co-developed training curricula Disseminated project results |

| St. Thomas Community Health Center and Wellness Center stthomaschc.org/ | Community-based health care provider | Health care delivery Community outreach, engagement, and context |

Community-based health care provider Provided mental health services Supported proposal development Provided feedback on training sessions |

| Tulane Community Health Center at Covenant House tuchc.org | Community-based health care provider | Health care delivery Community outreach, engagement, and context |

Provided mental health services Supported proposal development Co-led training sessions Co-developed training curricula Disseminated project results |

| Tulane University School of Medicine tulane.edu/som/ | Research institution | Project management | Project management Supported proposal development Co-led training sessions Co-developed training curricula Disseminated project results |

| UCLA Health Services Research Center hsrcenter.ucla.edu/ | Research institution | Evidence-based mental health care models | Supported proposal development Co-led training sessions Co-developed training curricula Provided model implementation support Disseminated project results |

| University of Washington, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences uwpsychiatry.org/ | Research institution | Research institution Evidence-based mental health care models |

Supported proposal development Co-led training sessions Co-developed training curricula Provided model implementation support Disseminated project results |

Fig 1.

Elements of Collaborative Care

Results

Workforce Training

The council developed training curricula and other products to support agencies, primary care physicians, therapists, social workers, care managers, case managers, and community health workers in implementing evidence-based practices. In the context of seven free, open-enrollment trainings offered between 2008 and 2010, community and academic co-leads taught to over 400 participants curricula involving small group discussion, skill practice sessions, and larger lectures. All attendees participated in collective seminars focused on developing organizational capacity to implement elements of collaborative care. Breakout sessions developed profession-specific skills. Curricular elements were modified by the project council over time to reflect trainee feedback (Table 2), community partner needs, and the transitioning landscape of community recovery. The project council added for all participants sessions on team building, networking, plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles, and communication to enhance care coordination. Community health workers and case managers received requested information on cultural competency, serious mental illness skills, and self-care. Training in cognitive behavioral therapy came to include an advanced track for previous attendees desirous of further skill development (Table 3).

Table 2.

Course ratings and sample qualitative feedback of MHIT training participants*

| Training seminar date | Overall course rating (1=poor, 5=excellent) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| July 2008 (n=42) | 4.9 | This will be an ongoing and continuing process…together we can make this mental health approach to recovery work. The presenters worked very hard, and the effect, expertise and energy are appreciated. Nice flexibility to meet audience needs. |

| October 2008 (n=42) | 4.7 | I learned some useful skills and will apply them. I believe New Orleans could benefit from a second training. There should have been more information given by the presenters and less input from the attendees. I would love for this course to continue. We needed discussion of examples relevant to the city of New Orleans, a city rebuilding post disaster. Excellent training. |

| February 2009 (n=134) | 4.73 | (Presenters) were exceptional. They interacted with the audience, made examples applicable and were coherent and reflective. This is better than grad school! The materials are so very helpful to case managers. This was a fantastic introduction to CBT. The session on communicating effectively to optimize treatment was excellent. The sharing and networking was very fruitful. Self-care assessment worksheet was fabulous. Very organized. Excellent role-playing practice. The CBT info was presented very quickly. As a new comer, it was a bit difficult to keep up with the pace. |

| May 2009 (n=80) | 4.56 | I like the fact that we met together—both outreach and clinical. The communicating effectively piece was extremely important as a means of making more informed and ethical decisions. Could maybe spend more time on how to do PDSA cycles and evaluate them. Would like more opportunity to network. PTSD: More theory and less case study. We all know the cases. We need treatment techniques. Also more focus on resilience and protective factors. This CBT course allowed me to open my ideas, correct and refine them and enable me to rationally learn, step-by-step on how to do this work. |

| August 2009 (n=57) | 4.69 | I liked the idea you involved community members from New Orleans in the training. The serious mental illness was a big help to me. It helped me to understand what’s really going on with certain clients. The presentations continue to be relevant and helpful to my work. Expected actual self-care session, not just a discussion-although it was a good discussion. More time set aside for networking. Loved the case studies and role playing. |

| December 2009 (n=70) | 4.67 | The role plays for suicide were very engaging and essential. CBT: Great training, great educators, great info. Training was very helpful. Loved the self care portion (not only for my own use, but for use with clients as well.) Very good program and useful because I find that generally no matter what the problem, depression is there and it immobilizes the person to act. |

| March 2010 (n=43) | 4.54 | What about asking a client or two to come and present? The interaction and information…related very much to what I do as an outreach worker. I was able to learn some new tools and put them into practice. Each session has offered additional useful information and reinforcement of previous learning. Professional presentation. Very helpful. Continue…doing presentations and activities combined. It’s like a hands-on experience while you’re learning. |

MHIT participants reported on several other measures including instructor knowledge, instruction materials, and applicability of knowledge and skills gained. Across all seven training seminars, mean scores for all measures were consistently between four and five on a five point Likert scale.

Table 3.

Evolution of MHIT curricular content

| July 2008 participants: 82 | October 2008 participants: 67 | February 2009 participants: 113 | May 2009 participants: 95 | August 2009 participants: 76 | December 2009 participants: 93 | March 2010 participants: 57 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants |

|

|

Previous topics plus:

|

Previous topics plus:

|

|

|

|

| Primary care providers |

|

Previous topics plus:

|

Previous topics | Previous topics | No sessions offered for primary care providers | No sessions offered for primary care providers | No sessions offered for primary care providers |

| CHWs and case managers |

|

Previous topics plus:

|

Previous topics plus:

|

|

Review of CHW training program successes

|

May 2009 topics plus:

|

Previous topics plus:

|

| Therapists | Overview of evidence-based therapy

|

Previous topics plus:

|

Previous topics plus:

|

CBT

|

|

|

Advanced CBT |

| Non-prescribing primary care staff (nurses, administrators, care managers) |

|

|

No sessions offered for non-prescribing primary care staff | No sessions offered for non-prescribing primary care staff | No sessions offered for non-prescribing primary care staff |

|

Topics for administrators

|

Resource Support

The project provided financial support and offered more targeted technical assistance to eight community-based organizations to help build capacity for community mental health services as well. Approximately 80% of total project funding was allocated to community agencies, with such assistance primarily facilitating agency hires of clinical and para-clinical staff, including physicians, therapists, care managers, and community health workers. During the two-year project period these agencies collectively delivered over 110,000 mental health services including individual and group therapy, screenings, referrals, and outreach. Technical assistance included weekly support calls to assist teams from primary care clinics that were implementing elements of collaborative care, such as developing patient registries or systems of care management. Academic partners also offered community-based agencies support in implementing an evidence-based model of cognitive behavioral therapy.

Linkages

The project further sought to develop novel linkages among community agencies and providers by facilitating new partnerships, inter-agency communication, and understanding of how agencies and providers may rely on one another as resources. Trainings included round-robin information exchanges to permit providers and potential collaborators to meet, to share information about services at their respective agencies, to collect relevant contact numbers, and to identify opportunities to work together. Existing community resource guides were expanded, building on a longer standing collaboration of Common Ground Health Clinic and REACH NOLA, and updated guides were distributed widely in print and online versions.29

Trainees in cognitive behavioral therapy developed regular provider meetings to discuss advancement of evidence-based psychotherapy in the broader community. Community health workers initiated monthly meetings to discuss opportunities and challenges in outreach, screening, education, referral, and peer support across their agencies. Efforts were piloted to enable community organizations to make referrals to one another using co-developed protocols. Multiple project products were co-developed and/or distributed for wider community use, some of which may have potential for utility in other post-disaster or low-resource settings (Table 4).

Table 4.

MHIT products and contributions

| Target audience | Product: website |

|---|---|

| Community members and community health workers | Depression can be treated information sheet: reachnola.org/pdfs/depressioncanbetreated.pdf PTSD Fact sheet from National Center for PTSD: reachnola.org/pdfs/howisptsdmeasured.pdf Self-care and self-help following disasters from National Center for PTSD: reachnola.org/pdfs/selfhelpfollowingdisasters.pdf About depression presentation: reachnola.org/pdfs/aboutdepressionpresentation.pdf Greater New Orleans Community Resource Guide: reachnola.org/pdfs/communityresourceguide_jan09.pdf |

| Community health workers and case managers | CHW training videos: reachnola.org/mhittrainingvideos.php Mental health safety and emergencies: reachnola.org/pdfs/mentalhealthsafetyandemergencies.pdf Problem solving skills presentation: reachnola.org/pdfs/problemsolvingskills_oct08.pdf Client services log: reachnola.org/pdfs/serviceslog.pdf REACH NOLA Mental Health Outreach Manual: reachnola.org/pdfs/reachnolamentalhealthoutreachmanual2009.pdf REACH NOLA Mental Health Outreach Trainers Manual: reachnola.org/pdfs/REACHNOLAMentalHealthOutreachTrainersGuide.pdf HIPPA and confidentiality rules: reachnola.org/pdfs/hipparules_jun2009.pdf Authorization for release of health information: reachnola.org/pdfs/healthinformationreleaseauthorizationform.pdf Client consent form: reachnola.org/pdfs/clientconsentform_template.pdf Confidentiality agreement: reachnola.org/pdfs/confidentialityagreement_template.pdf Referral form: reachnola.org/pdfs/referalform_template.pdf |

| Therapists | Psychological first aid (courtesy of National Center for PTSD): reachnola.org/pdfs/ptsdmanual.pdf Cognitive behavioral therapy introduction and application training videos: reachnola.org/mhittrainingvideos.php CBT Manuals (courtesy of UCLA Health Services Research Center): www.hsrcenter.ucla.edu/research/wecare/CBTmanuals.html Problem Solving Therapy (PST) Manual: reachnola.org/pdfs/pstmanual.pdf PST problem list: reachnola.org/pdfs/pstproblemlist.pdf Problem solving worksheet: reachnola.org/pdfs/pstworksheet.pdf Problem solving checklist: reachnola.org/pdfs/pstchecklist.pdf |

| Therapists and community health workers | Helping someone schedule activities: reachnola.org/pdfs/helpingsomeonescheduleactivities.pdf Scheduling activities: reachnola.org/pdfs/schedulingactivities.pdf |

| Primary care providers | Depression and PTSD screening, treatment, and medication management training videos: reachnola.org/mhittrainingvideos.php Collaborative care for treating depression-PCP presentation: reachnola.org/pdfs/CollaborativeCareforTreatingDepression.pdf Depression and anxiety-primary care providers presentation: reachnola.org/pdfs/DepressionandAnxietySlides.pdf |

| Primary care providers, health care administrators, therapists, psychiatrists, community health workers, case managers and care managers | Introduction to the collaborative care model presentation: reachnola.org/pdfs/introcollaborativecaremodel.pdf Implementing change presentation: reachnola.org/pdfs/ImplementingChange-PDSAQI.pdf Team building, networking, quality improvement, and communicating effectively presentation: reachnola.org/pdfs/TeamBuildingNetworkingQICommunication.pdf Care management key components: reachnola.org/pdfs/caremanagmentkeycomponents_jun09.pdf Patient path to wellness: Evidence-based treatment for depression and/or PTSD: reachnola.org/pdfs/patientpathtowellness.pdf Relapse prevention plan: reachnola.org/pdfs/relapsepreventionplan.pdf Team building process forms: reachnola.org/pdfs/teambuildingprocessforms.pdf Introduce the care team: reachnola.org/pdfs/introducecareteam.pdf Commonly prescribed psychotrophic medications: reachnola.org/pdfs/medicationcard.pdf PHQ-2 Depression Screener: reachnola.org/pdfs/phq2depressionscreener.pdf PHQ-9 Depression Screener (English): reachnola.org/pdfs/phq9depressionscreener_english.pdf PHQ-9 Depression Screener (Spanish): reachnola.org/pdfs/phq9depressionscreener_spanish.pdf Primary Care PTSD Screener: reachnola.org/pdfs/ptsdpcposttraumaticstressdisorderscreener.pdf Combined Primary Care PTSD Screener and PHQ-2: reachnola.org/pdfs/combindephq2andptsdpcscreener.pdf GAD 7 Anxiety Screener: reachnola.org/pdfs/gad7anxietyscreener.pdf AUDIT-CAGE Abuse and Dependence Screener: reachnola.org/pdfs/auditgageabusedependencescreener.pdf PTSD and seasonal anxiety presentation part 1: reachnola.org/pdfs/PTSDandSeasonalAnxiety-Part1.pdf PTSD and seasonal anxiety presentation part 2: reachnola.org/pdfs/PTSDandSeasonalAnxiety-Part2.pdf |

Although MHIT was a services- and capacity building-focused project, community and academic partners also collaborated on pilot data collection, interpretation, and dissemination efforts to document opportunities for advancement of understanding and processes of shared learning.17 All pilot research efforts affiliated with the project were reviewed and either approved or found to be exempt by each the RAND Corporation and Tulane University Institutional Review Boards. As examples, Bentham et al in this issue13 describe the results of a community-academic partnered approach to implementing a model of collaborative care for depression in primary care safety net clinics. Wennerstrom et al24 describe community-academic participatory development of a community health worker training program for post-disaster mental health needs. Ngo et al15 describe implementation of a cognitive behavioral therapy training program to support local capacity for delivery of evidence-based therapy and training.

Discussion/Conclusion

Post-disaster communities frequently struggle with a predictably complex web of simultaneous challenges – limited basic infrastructure, governmental and nongovernmental disorganization and communication failures, decrements of health and social services capacity, exacerbated socioeconomic and racial disparities among disaster survivors, extraordinarily high levels of human need (including among service providers), heightened economic uncertainty and loss, and a pressing need to re-assess and address risk mitigation practices and capacities. In this context, a high prevalence of mental health problems and unmet mental health needs coincident with the disaster, when left unaddressed, may cripple or dramatically prolong individual, family, or community recovery.

This article describes a participatory, health-focused model of community recovery that began with addressing emerging, unmet mental health needs using a disparities-conscious partnership framework as one of the principle mechanisms for intervention. Mental health needs were addressed by: 1) investment in infrastructure and services capacity among small and medium sized non-profit organizations working in disaster-impacted, low resource settings; 2) developing networks and partnerships among health and social service providers that encourage recovery and resilience; 3) training for professionals and non-clinical staff, agency technical assistance, and quality improvement initiatives to improve availability of high quality mental health care for survivors; and 4) development of community resources to promote education, access, and appropriate utilization of services. These interventions promoted concurrent development of new community and academic partnered leadership for the disaster recovery.14 This model of leadership development may continue to be impactful over time in these communities as sustained networks emerge that facilitate ongoing resource-sharing and knowledge transfer, foster further development of existing community strengths, and create new opportunities for community leadership of recovery efforts, including as trained community health workers.

This project has several limitations. The project was funded principally as a services and capacity building project, not as research, and this framework constrained the prospective design considerations as well as collection and analysis of data that would be necessary to more rigorously evaluate both processes and outcomes. While many elements of the project are likely to be generalizable to broader application and testing, it is possible that aspects of implementation of the project in the post-Katrina environment in New Orleans are in some ways unique. Project partners in many instances were impacted by the disaster themselves, a circumstance which may have uniquely influenced project development and implementation. Additional research is necessary to understand how elements of this model may be applied to impact individual and community recovery, build agency and provider capacity, or encourage resilience.

New Orleans, as with many disaster-impacted communities, faces the risk of recurrent and even seasonal disaster that can exacerbate existing socioeconomic and health disparities. Development of a better understanding of means to expedite mental health and community recovery, and to encourage resilience is important not only to New Orleans but to any disaster-prone community. New and timely research to test evidence-informed models of recovery, and interventions that may promote mental health or resilience, may prove to be of lasting value to diverse populations and communities, domestically and abroad. The costs of research to test evidence-informed models of recovery, and interventions that may promote individual and community resilience, may prove to be not only cost-effective for governments, philanthropy, and service providers, but capable of mitigating substantial human suffering.

References

- 1.Wang PS, Gruber MJ, Powers RE, et al. Mental health service use among Hurricane Katrina survivors in the eight months after the disaster. Psychiat Serv. 2007;58(11):1403–1411. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.11.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Galea S, Jones RT, Parker HA. Mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(12):930–939. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.033019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sastry N, VanLandingham M. One year later: Mental illness prevalence and disparities among New Orleans residents displaced by Hurricane Katrina. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:S725–S731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Springgate B, Allen C, Jones C, et al. Rapid community participatory assessment of health care in post-storm New Orleans. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:S237–S243. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pope J. N.O. is short on doctors, dentists: City becomes eligible for recruitment help. Times Picayune Metro. 2006 Apr 26;:1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed June 17, 2010];Low-income adults in New Orleans in 2008: Who are they and how are they faring? http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/7833.pdf.

- 7.Wells K, Klap R, Koike A, Sherbourne C. Ethnic disparities in unmet need for alcoholism, drug abuse and mental health care. Am J Psychiat. 2001;158(12):2027–2032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoenbam M, Butler B, Kataoka S, et al. Promoting mental health recovery after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita: what can be done at what cost. Arch Gen Psychiat. 2009;66(8):906–914. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alegria M, Chatterji P, Wells K, et al. Disparity in access to and quality of depression treatment among racial and ethnic minorities in the US. Psychiat Serv. 2008;59(11):1264–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.11.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne CD, et al. Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):613–630. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones L, Wells KB. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297:407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells K, Jones L. “Research” in community-partnered participatory research. JAMA. 2009;302:320–321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentham W, Vannoy SD, Badger K, Wennerstrom A, Springgate B. Opportunities and challenges of implementing collaborative mental health care. Post-Katrina New Orleans. 2011;21(Suppl 1):s1-xxx–s1-yyy. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyers D, Allen C, Dunn D, Wennerstrom A, Springgate B. Community perspectives on post-Katrina mental health recovery in New Orleans. 2011;21(Suppl 1):s1-xxx–s1-yyy. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngo VK, Centanni A, Wong E, Wennerstrom A, Miranda J. Building capacity for cognitive behavioral therapy delivery in resource poor disaster impacted contexts. 2011;21(Suppl 1):s1-xxx–s1-yyy. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.REACH NOLA. [Accessed January 3, 2011]; Available at www.reachnola.org.

- 17.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Springgate B, Allen C, Jones C, et al. Community-based participatory assessment of health care needs in post-Katrina New Orleans. In: Gilliam M, Fischbach S, Wolf L, Azikiwe N, Tegeler P, editors. Rebuilding a healthy New Orleans. Final conference report of the New Orleans health disparities initiative. Poverty and Race Research Action Council; [Accessed: August 23, 2010]. http://www.prrac.org/pdf/rebuild_healthy_nola.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Springgate B, Allen C, Butler B, Wells K. Taking action following a disaster through community-academic partnerships: Funding and using the win-win in a crisis. Oral presentation. The Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program National Meeting; Fort Lauderdale, Florida. November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnick J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, Belin T. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(1):57. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wennerstrom A, Vannoy SD, Allen C, Meyers D, O’Toole E, Wells K, Springgate B. Community-based participatory development of a community health worker mental health outreach role to extend collaborative care in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethn Dis. 2011;21(Suppl 1):s1-xxx–s1-yyy. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yun K, Lurie N, Hyde PS. Moving mental health into the disaster preparedness spotlight. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(13):1193–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1008304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bluthenthal RN, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, et al. Witness for Wellness: Preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(suppl 1):S1-18–S1-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Sep;62(9):953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miranda J, Woo S, Lagomasino I, Hepner K, Wiseman S, Munoz R. [Accessed January 3, 2011];Group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression. http://www.hsrcenter.ucla.edu/research/wecare/CBTmanuals.html.

- 29.REACH NOLA. [Accessed January 3, 2011];Greater New Orleans Resource Guide. http://reachnola.org/pdfs/Main%20Guide%20JULY%202010-1.pdf.