Abstract

Context:

Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) is a phosphaturic hormone that also inhibits calcitriol synthesis.

Objective:

Our objective was to evaluate the relationships of plasma FGF23 concentrations with bone mineral density (BMD) and hip fracture in community-dwelling older adults.

Design and Setting:

Linear regression and Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine the associations of plasma FGF23 concentrations with BMD and incident hip fracture, respectively. Analyses were also stratified by chronic kidney disease.

Participants:

Participants included 2008 women and 1329 men ≥65 years from the 1996 to 1997 Cardiovascular Health Study visit.

Main Outcome Measures:

Dual x-ray absorptiometry measured total hip (TH) and lumbar spine (LS) BMD in 1291 participants. Hip fracture incidence was assessed prospectively through June 30, 2008 by hospitalization records in all participants.

Results:

Women had higher plasma FGF23 concentrations than men (75 [56–107] vs 66 [interquartile range = 52–92] relative units/mL; P < .001). After adjustment, higher FGF23 concentrations were associated with greater total hip and lumbar spine BMD in men only (β per doubling of FGF23 = 0.02, with 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.001–0.04 g/cm2, and 0.03 with 95% CI = 0.01–0.06 g/cm2). During 9.6 ± 5.1–11.0 years of follow-up, 328 hip fractures occurred. Higher FGF23 concentrations were not associated with hip fracture risk in women or men (adjusted hazard ratio = 0.95, with 95% CI = 0.78–1.15, and 1.09 with 95% CI = 0.82–1.46 per doubling of FGF23). Results did not differ by chronic kidney disease status (P > .4 for interactions).

Conclusions:

In this large prospective cohort of community-dwelling older adults, higher FGF23 concentrations were weakly associated with greater lumbar spine and total hip BMD but not with hip fracture risk.

Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) is secreted into the bloodstream by osteoblasts and osteocytes and regulates phosphorus homeostasis (1, 2). It induces phosphaturia by decreasing renal tubular reabsorption of phosphorus through decreased expression of the sodium-dependent phosphate transporter (2) and inhibits PTH secretion by direct action on the Klotho/FGF23 receptor in the parathyroid gland (3). FGF23 also decreases calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D]) concentrations by inhibiting renal 1α-hydroxylase and stimulating 24-hydroxylase (4). Higher FGF23 concentrations are a strong and independent risk factor for death and cardiovascular events, particularly among people with chronic kidney disease (CKD), who frequently have very high circulating concentrations of FGF23 (5–9). Despite its origins in the bone and central role in mineral metabolism, the relationship of FGF23 with bone disease has not been thoroughly examined.

There are various potential mechanisms by which high FGF23 concentrations could adversely affect bone, most of which are based on data from animal models (10, 11) and cell culture studies (12). Overexpression of FGF23 in transgenic mice leads to osteomalacia, calcitriol deficiency, and decreased serum phosphorus concentrations (10, 11). In humans, rare paraneoplastic syndromes of FGF23 excess have similar bone phenotypes (13). By inducing phosphorus excretion and decreasing 1,25(OH)2D, FGF23 could adversely affect bone mineralization through the resulting negative phosphorus balance and 1,25(OH)2 D deficiency. FGF23 may also have direct effects on bone, because it has direct phosphate-independent effects to suppress bone mineralization (12).

Older adults have higher risk of bone loss and fractures. The relationship of FGF23 with hip fracture risk in this population is largely unknown. To our knowledge, published data evaluating the association of FGF23 concentrations with bone mineral density (BMD) and fracture have been limited to men with a relatively short follow-up (14, 15). Thus, our objective was to evaluate the relationships of plasma FGF23 concentrations with BMD and hip fracture in a relatively large sample of community-dwelling older women and men (16, 17). A priori, we hypothesized that higher plasma FGF23 concentration would be associated with lower BMD and greater risk of incident hip fracture during follow-up in both women and men.

Subjects and Methods

Participants

The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) is a prospective, longitudinal study of older community-dwelling adults. The study methods have been previously described (16). Participants were recruited from Medicare eligibility lists at 4 locations: Forsyth County, North Carolina; Sacramento County, California; Washington County, Maryland; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. To be eligible, participants were required to be community-dwelling, aged 65 or older, expected to remain in the area for 3 years after recruitment, not receiving active treatment for cancer, and able to give informed consent without a proxy. The original cohort was recruited in 1989 through 1990, and a second cohort of 687 predominantly black individuals was recruited in 1992 through 1993, resulting in 5888 participants, all of whom provided informed consent. We measured FGF23 in plasma samples collected at the 1996/1997 study visit. This visit was selected because it was the first visit at which morning urine samples were collected and measured for albumin-to-creatinine ratios (ACRs), which we hypothesized might confound the relationships of FGF23 with fractures and other outcomes (7). Among 3406 individuals who participated in the 1996/1997 study visit, 69 individuals with insufficient blood specimens for FGF23 measurement were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 3337 participants for this analysis. Two sites, Pittsburgh and Sacramento County, measured BMD during the 1994/1995 visit, 1.8 ± 0.4 years before the plasma FGF23 measurements. Hip fracture outcomes were evaluated from the 1996/1997 study visit until June 30, 2008, death, or last contact.

Study variables

The primary independent variable was plasma FGF23 concentrations. Fasting (8 hours) EDTA plasma specimens collected at the 1996/1997 study visit were stored at −70°C until 2010 when they were thawed and measured for FGF23. Previously thawed specimens were not used. FGF23 was measured using a commercially available ELISA kit (Immutopics, San Clemente, California) (18) that recognizes 2 epitopes on the C-terminal side of FGF23. Our estimates of the intra-assay and interassay coefficients of variation ranged from 7.4% to 10.6%.

The dependent variables of interest were BMD of the total hip and lumbar spine in cross-section and incident hip fracture during follow-up. BMD was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (QDR 2000 or 2000+; Hologic, Inc, Bedford, Massachusetts). All scans were completed using the array beam mode. Standardized positioning and use of QDR software was based on the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Scans were read centrally and monitored for quality control at the University of California, San Francisco, reading center with Hologic software version 7.10, as described previously (19). The coefficient of variation for the total hip and lumbar spine BMD was <0.75%.

Incident hip fractures were indentified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes from hospitalization records. CHS prospectively gathers all hospitalization data, including discharge summaries, from participants every 6 months. To ensure completeness of hospitalization records, data were checked against Medicare claims data to identify any hospitalizations that were not reported by the participant. Hip fracture was defined as ICD-9 code of 820.xx. Admissions for complications of hip fracture, such as osteomyelitis or hip prosthesis revision, were excluded.

Characteristics related to FGF23, decreased BMD, and risk of hip fracture were selected a priori as potential covariates, and all were measured concurrent to FGF23 measurement at the 1996/1997 study visit (baseline). Race and alcohol use was determined by participant self-report. Diabetes was defined as the use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents or fasting glucose level ≥126 mg/dL. Body weight was measured using a calibrated balance beam scale. Height was measured with a wall-mounted stadiometer. Smoking was defined as current, former, or never. Use of selected prescription medications with the potential to affect bone metabolism or fracture risk (thiazide diuretics, and for women, estrogen) was ascertained from a review of prescription bottle labels by interviewers (20). A physical activity score (PAS), taking into account the type and intensity of physical activity reported by CHS participants, was calculated by summing kilocalories expended per week and walking pace. It is an ordinal score with a range of 2 to 8, with higher scores representing more physical activity. The PAS has been used in previous epidemiological studies in CHS (21). Cystatin C was measured using a BNII nephelometer (Dade Behring, Deerfield, Illinois) and was chosen as the primary measure of kidney function (22). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated for cystatin C using an equation derived from a pooling of cohorts that used iothalamate clearance as the criterion standard (eGFR = 76.7 × cystatin C−1.19) (23). Urine ACR was determined from random morning urine samples; urine albumin was measured by rate nephelometry using the Array 360 CE protein analyzer (Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, California), and urine creatinine was measured on a Kodak Ektachem 700 analyzer (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, New York). The urine ACR was calculated in milligrams per gram. CKD was defined as an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or by the presence of urine ACR ≥30 mg/g (23). Osteoporosis was defined based on the diagnostic criteria set forth by the World Health Organization (24, 25).

Statistical analyses

Due to the established differences in bone loss and fracture risk between women and men, sex-specific FGF23 quartiles were evaluated, and main analyses were stratified by sex a priori (17). Univariate associations of clinical and demographic variables with sex-specific quartiles of plasma FGF23 were compared using linear trend tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. The relationship of plasma FGF23 concentrations with BMD was assessed with linear regression models. We explored the functional form of FGF23 with splines. The longitudinal association between FGF23 and incident hip fracture was examined using Cox proportional hazards. Participants were censored at death or loss of follow-up. We explored graphically and numerically proportional hazards. All analyses evaluated FGF23 quartiles with the lowest quartile serving as the reference category. In addition, we examined FGF23 as a continuous predictor variable after log2 transformation, to facilitate interpretation of the parameter coefficient as per doubling of FGF23. The initial models in all analyses were adjusted for age and race. The multivariable-adjusted models further included smoking, alcohol, weight, height, diabetes, thiazide use, PAS (score 2–3 [reference] compared with scores 4–6 and 7–8), and in women, estrogen use (model 2). Further adjustments included eGFR and urine ACR (model 3). We evaluated an FGF23 × CKD interaction term in the final adjusted model for each outcome. Two-tailed values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participant characteristics at baseline

Among the 3337 study participants, the mean age was 78 ± 5 years, 60% (n = 2008) were women, and 16% (n = 537) were black. Among women, 17% were using estrogen. The mean eGFR was 71 ± 20 mL/min/1.73 m2, the median urine ACR was 8.8 (interquartile range [IQR] 4.7–20.4) mg/g, and 40% had chronic kidney disease (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or urine ACR ≥30 mg/g). The median plasma FGF23 concentration was 70 (IQR 53–99) RU/mL.

Women had higher plasma FGF23 concentrations than men (median of 75 [IQR 56–107] vs 66 [IQR 52–92] relative units/mL [RU/mL]; P < .001). We therefore categorized participants by sex-specific quartiles of FGF23 to facilitate comparison of the associations separately in women and men. Compared with women and men in the lowest FGF23 quartile, those with higher plasma FGF23 concentrations were older, more frequently white, more likely to have diabetes; had lower eGFR and higher urine ACR; and reported a higher number of falls and decreased physical activity (Table 1). Women with higher plasma FGF23 concentrations were also more likely to smoke and use thiazide diuretics and were less likely to be taking estrogen or to report alcohol consumption; similar trends were observed in men, albeit associations did not reach statistical significance in this group.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Sex-Specific Quartiles of FGF23a

| Total | Quartiles |

P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |||

| Women | ||||||

| n | 2008 | 502 | 503 | 501 | 502 | |

| FGF-23, RU/mL | <56.2 | 56.2–74.5 | 74.5–106.5 | >106.5 | ||

| Age, y | 78 ± 5 | 77 ± 5 | 78 ± 5 | 78 ± 5 | 79 ± 5 | <.001 |

| Race (black) | 350 (17) | 116 (23) | 84 (17) | 66 (13) | 84 (17) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 262 (13) | 42 (8) | 48 (10) | 76 (15) | 96 (19) | <.001 |

| Current smoking | 136 (7) | 20 (4) | 22 (5) | 49 (10) | 45 (9) | <.001 |

| Alcohol (>7 drinks/wk) | 124 (6) | 43 (9) | 29 (6) | 26 (5) | 26 (5) | .02 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 384 (19) | 77 (15) | 86 (17) | 95 (19) | 126 (25) | <.001 |

| Estrogen | 338 (17) | 105 (21) | 93 (19) | 75 (15) | 65 (13) | <.001 |

| Height, cm | 158 ± 6 | 158 ± 6 | 158 ± 6 | 158 ± 6 | 158 ± 6 | .38 |

| Weight, lb | 150 ± 31 | 145 ± 29 | 147 ± 27 | 152 ± 30 | 155 ± 36 | <.001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 72 ± 19 | 83 ± 17 | 76 ± 17 | 70 ± 16 | 60 ± 19 | <.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||||

| <45 | 159 (8) | 2 (1) | 12 (2) | 30 (6) | 115 (23) | |

| 45–60 | 312 (16) | 32 (6) | 69 (14) | 85 (17) | 126 (25) | |

| >60–90 | 1207 (60) | 312 (62) | 325 (65) | 337 (67) | 233 (46) | |

| >90 | 330 (16) | 156 (31) | 97 (19) | 49 (10) | 28 (6) | |

| Urine ACR, mg/gb | 10.0 (5.6–20.8) | 8.4 (5.2–16.3) | 9.4 (5.5–16.1) | 9.6 (5.4–20.2) | 14.1 (6.7–46.5) | <.001 |

| Total hip BMD, g/cm2 | 0.75 ± 0.14 | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 0.74 ± 0.13 | 0.76 ± 0.14 | 0.77 ± 0.16 | .09 |

| Lumbar spine BMD, g/cm2 | 0.94 ± 0.24 | 0.92 ± 0.21 | 0.92 ± 0.22 | 0.95 ± 0.26 | 0.96 ± 0.25 | .07 |

| Osteoporosis (WHO criteria) | 273/750 (36) | 75/213 (35) | 9/179 (39) | 8/198 (34) | 61/160 (38) | .3 |

| History of fallsc | 428/1987 (22) | 97/496 (20) | 96/501 (19) | 103/495 (21) | 132/495 (27) | .02 |

| PAS | ||||||

| 2–3 | 649 (33) | 128 (26) | 140 (28) | 171 (35) | 210 (42) | <.001 |

| 4–6 | 1022 (52) | 264 (53) | 262 (53) | 255 (52) | 241 (49) | |

| 7–8 | 308 (16) | 104 (21) | 94 (19) | 64 (13) | 46 (9) | |

| Men | ||||||

| n | 1329 | 333 | 332 | 332 | 332 | |

| FGF-23, RU/mL | <51.8 | 51.8–66.4 | 66.3–92.1 | >92.1 | ||

| Age, y | 78 ± 5 | 77 ± 4 | 78 ± 4 | 79 ± 5 | 79 ± 6 | <.001 |

| Race (black) | 188 (14) | 79 (24) | 49 (18) | 27 (8) | 33 (10) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 234 (18) | 40 (12) | 56 (17) | 57 (17) | 81 (24) | <.001 |

| Current smoking | 110 (8) | 22 (7) | 23 (7) | 29 (9) | 36 (11) | .2 |

| Alcohol (>7 drinks/wk) | 217 (16) | 69 (21) | 51 (16) | 56 (17) | 41 (12) | .07 |

| Thiazide diuretics | 171 (13) | 32 (10) | 40 (12) | 51 (15) | 48 (15) | .11 |

| Height, cm | 172 ± 7 | 172 ± 7 | 172 ± 7 | 173 ± 7 | 172 ± 7 | .17 |

| Weight, lb | 174 ± 30 | 173 ± 28 | 173 ± 26 | 175 ± 27 | 175 ± 30 | .13 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 68 ± 19 | 77 ± 16 | 73 ± 19 | 66 ± 16 | 55 ± 19 | <.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | ||||||

| <45 | 148 (11) | 4 (1) | 8 (2) | 27 (8) | 109 (33) | |

| 45–60 | 282 (21) | 33 (10) | 60 (18) | 96 (29) | 93 (28) | |

| >60–90 | 757 (57) | 230 (69) | 225 (68) | 185 (56) | 117 (35) | |

| >90 | 142 (11) | 66 (20) | 39 (12) | 24 (7) | 13 (4) | |

| Urine ACR, mg/gb | 10.4 (5.0–26.6) | 8.1 (4.4–16.7) | 8.9 (4.7–21.2) | 10.9 (5.7–23.7) | 18.1 (6.8–81.9) | <.001 |

| Total hip BMD, g/cm2 | 0.95 ± 0.16 | 0.94 ± 0.16 | 0.94 ± 0.15 | 0.97 ± 0.15 | 0.94 ± 0.18 | .41 |

| Lumbar spine BMD, g/cm2 | 1.13 ± 0.23 | 1.09 ± 0.22 | 1.11 ± 0.23 | 1.15 ± 0.24 | 1.17 ± 0.24 | <.001 |

| Osteoporosis (WHO criteria) | 24/534 (5) | 9/156 (6) | 5/127 (4) | 2/121 (2) | 8/130 (6) | .4 |

| History of fallsc | 192/1318 (15) | 54/330 (16) | 38/328 (12) | 38/330 (12) | 62/330 (19) | .02 |

| PAS | <.001 | |||||

| 2–3 | 254 (19) | 51 (16) | 50 (15) | 57 (17) | 96 (29) | |

| 4–6 | 661 (50) | 161 (49) | 167 (51) | 167 (51) | 166 (51) | |

| 7–8 | 398 (30) | 115 (35) | 112 (34) | 105 (32) | 66 (20) | |

Data are shown as mean ± SD or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Median (IQR).

Self-report of falls within the last year at the 1996/1997 study visit.

FGF23 concentration and BMD

BMD data were obtained at 2 of the 4 field centers at a study visit 2 years before FGF23 concentrations were measured. At these 2 field centers, 1796 participants were seen at this clinical examination, among whom 1291 (754 female) completed the DXA ancillary study and were included in this analysis. Participants who had a DXA scan were more likely to have a history of smoking and had higher eGFR than the remaining 505 participants who participated in the study visit but not in the DXA ancillary study. Compared with the entire cohort (from all study visit sites) without DXA scan (n = 2046), those with DXA were more likely to be black, consumed more alcohol, and were less likely to smoke (Supplemental Table 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org). Mean total hip BMD for women and men were 0.75 ± 0.14 and 0.95 ± 0.16 g/cm2, respectively. The mean lumbar spine BMD was 0.94 ± 0.24 and 1.13 ± 0.23 g/cm2 in women and men, respectively. Table 1 shows total hip and lumbar spine BMD as well as the number of participants with osteoporosis.

The unadjusted association of FGF23 quartiles with total hip BMD was not significant in either sex (Table 2). In models adjusted for age and race, FGF23 concentrations within the third and fourth quartile were significantly associated with greater total hip BMD in women and men. Additional adjustment for kidney function and other bone disease risk factors attenuated the associations such that the associations were no longer statistically significant in either sex. However, when FGF23 was modeled as a continuous predictor variable, we observed a statistically significant relationship between higher FGF23 concentrations and greater total hip BMD in men only in the fully adjusted model (β = 0.02 g/cm2, with 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.001–0.04, per doubling of FGF23; P = .04). In contrast, there was no statistically significant relationship between 2-fold increases of FGF23 and total hip BMD in women. Results were similar irrespective of CKD status when both women and men were evaluated together and when evaluated separately (P for interaction >.40 for all).

Table 2.

Associations (β-Estimates) of Sex-Specific Quartiles of Baseline Plasma FGF23 Concentrations With Total Hip BMDa

| Quartiles |

Per Doubling of FGF23 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||

| Women | |||||

| FGF23, RU/mL | <56.2 | 56.2–74.5 | 74.5–106.5 | >106.5 | |

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | 0.01 (−0.01 to 0.04) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.05) | 0.01b (0.001–0.03) |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.004 (−0.02 to 0.03) | 0.04b (0.01–0.06) | 0.04b (0.01–0.07) | 0.02b (0.01–0.03) |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (Reference) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.04) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.04) | 0.01 (−0.001 to 0.02) |

| Model 3 | 1.00 (Reference) | −0.002 (−0.03 to 0.02) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.04) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.05) | 0.01 (0–0.02) |

| Men | |||||

| FGF23 (RU/mL) | <51.8 | 51.8–66.4 | 66.4–92.1 | >92.1 | |

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.002 (−0.04 to 0.04) | 0.03 (−0.004 to 0.07) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.04) | 0.001 (−0.02 to 0.02) |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.05) | 0.06b (0.02–0.10) | 0.04b (0.003–0.08) | 0.01 (−0.002 to 0.03) |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | 0.05b (0.02–0.09) | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.06) | 0.02 (−0.001 to 0.03) |

| Model 3 | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.04) | 0.05b (0.02–0.09) | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.07) | 0.02b (0.001–0.04) |

Total hip BMD was measured approximately 2 years before FGF23 concentration was obtained. Model 1 is adjusted for age and race. Model 2 is adjusted for model 1, smoking, alcohol, weight, height, diabetes, thiazide diuretics, PAS, and estrogen (in females). Model 3 is adjusted for model 2 plus eGFR and urine ACR.

P < .05.

Results were generally similar for lumbar spine BMD. In crude analyses, FGF23 concentrations in the fourth quartile were positively and significantly associated with greater lumbar spine BMD in men only (Supplemental Table 2). After adjusting for age and race, there was a consistent and statistically significant association of higher FGF23 concentrations in the third and fourth quartiles compared with the lowest quartile with higher lumbar spine BMD in both sexes. With full multivariable adjustment, this relationship was attenuated in women but remained present and statistically significant in men. We also observed an association between higher FGF23 concentrations and greater lumbar spine BMD in men when FGF23 was modeled continuously (β = 0.03 g/cm2 higher in lumbar spine BMD, with 95% CI = 0.01–0.06, per doubling FGF23; P = .02) in the fully adjusted model, whereas no statistically significant association was observed in women. As with total hip BMD, results were similar irrespective of CKD status (P for interaction >.50 for all). When corticosteroid use and calcium/vitamin D supplementation were added to the models, there was no meaningful change in the associations (data not shown).

FGF23 concentrations and risk of hip fracture

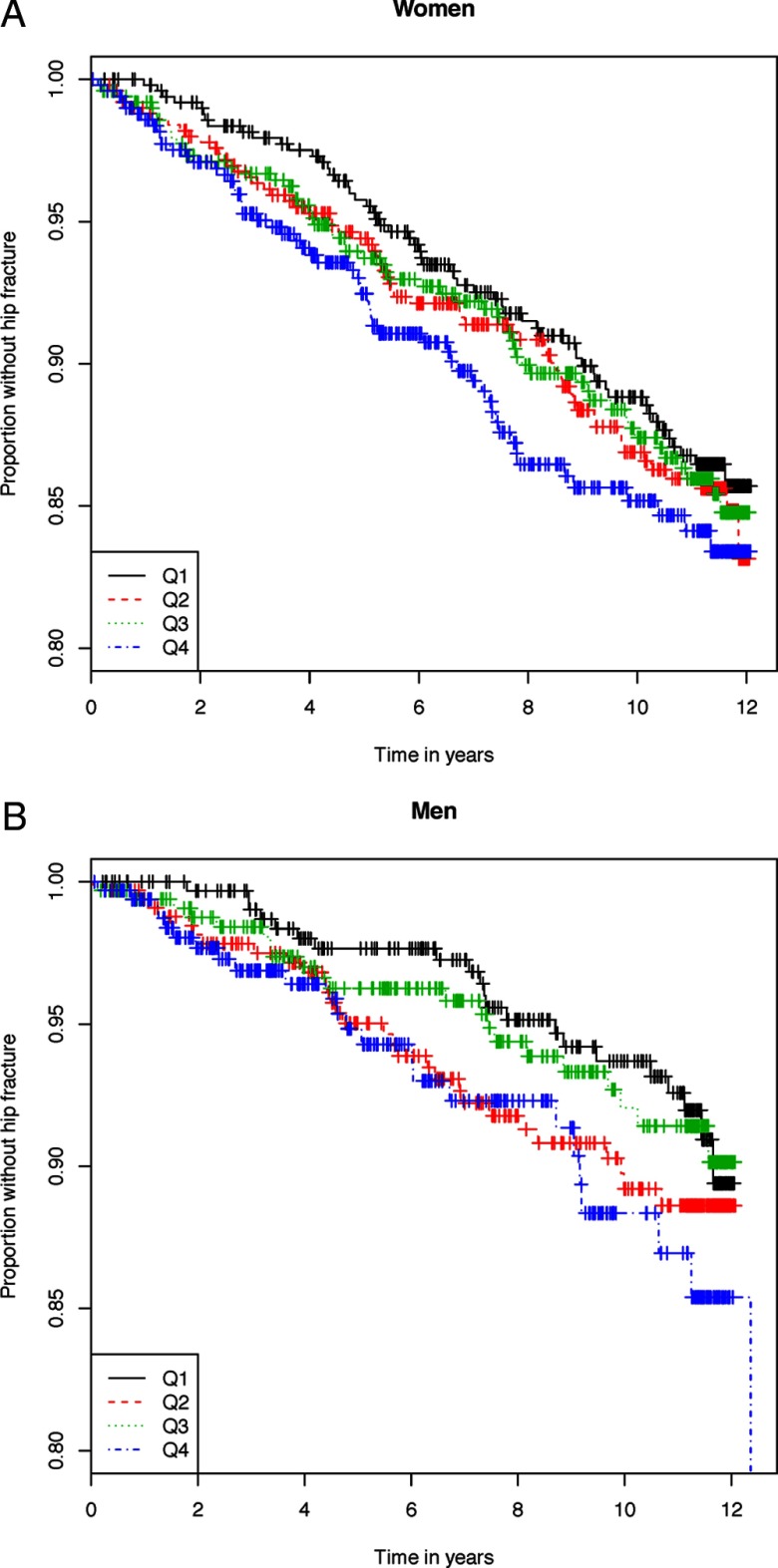

Among the 3337 participants, there were 27 346 person-years of follow-up during which 328 incident hip fractures occurred over a median follow-up of 9.6 (IQR = 5.1–11.0) years. Women had 233 hip fractures (1.37 hip fractures per 100 person-years), and men had 95 hip fractures (0.92 hip fractures per 100 person-years). Events and incidence rates for each FGF23 quartile are shown in Table 3. Kaplan-Meier curve analysis showed that the risk of incident fracture did not change with increasing concentrations of plasma FGF23 in either women or men (P = .51 and P = .22, respectively; Figure 1, A and B).

Table 3.

Associations of Sex-Specific Quartiles of Baseline Plasma FGF23 Concentrations with Risk (Hazard Ratios) of Incident Hip Fracturesa

| Quartiles |

Per Doubling of FGF23 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | ||

| Women | |||||

| FGF23, RU/mL | <56.2 | 56.2–74.5 | 74.5–106.5 | >106.5 | |

| Hip fracture events | 57 | 62 | 57 | 57 | |

| Incidence rateb | 1.23 | 1.37 | 1.34 | 1.58 | |

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.21 (0.78–1.61) | 1.10 (0.76–1.58) | 1.32 (0.92–1.91) | 1.07 (0.92–1.24) |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.05 (0.73–1.51) | 0.97 (0.67–1.4) | 1.08 (0.74–1.56) | 1.00 (0.85–1.17) |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.02 (0.71–1.48) | 0.89 (0.60–1.33) | 1.07 (0.72–1.59) | 0.99 (0.83–1.17) |

| Model 3 | 1.00 (Reference) | 0.94 (0.65–1.36) | 0.84 (0.56–1.25) | 0.89 (0.58–1.36) | 0.98 (0.77–1.12) |

| Men | |||||

| FGF23, RU/mL | <51.8 | 51.8–66.4 | 66.4–92.1 | >92.1 | |

| Hip fracture events | 21 | 29 | 21 | 24 | |

| Incidence rateb | 0.72 | 1.04 | 0.79 | 1.23 | |

| Unadjusted | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.44 (0.82–2.52) | 1.10 (0.60–2.01) | 1.75 (0.97–3.18) | 1.27c (1.01–1.60) |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.31 (0.75–2.31) | 0.89 (0.48–1.63) | 1.34 (0.73–2.44) | 1.19 (0.93–1.52) |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.19 (0.67–2.10) | 0.81 (0.44–1.51) | 1.21 (0.66–2.24) | 1.14 (0.88–1.47) |

| Model 3 | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.11 (0.63–1.97) | 0.72 (0.38–1.35) | 1.01 (0.53–1.94) | 1.08 (0.82–1.43) |

Model 1 is adjusted for age and race. Model 2 is adjusted for model 1, smoking, alcohol, weight, height, diabetes, thiazide diuretics, PAS, and estrogen (in females). Model 3 is adjusted for model 2 plus eGFR and urine ACR.

Per 100 person-years.

P < .05.

Figure 1.

A, Kaplan-Meier curves for the risk of incident hip fracture with increasing plasma FGF23 concentrations in women (P = .51). B, Kaplan-Meier curves for the risk of incident hip fracture with increasing plasma FGF23 concentrations in men (P = .22).

In analyses adjusted for age and race, higher plasma FGF23 concentrations by quartiles were not associated with an increased hazard of hip fracture risk in either sex. Results were similar in fully adjusted models (Table 3). No associations were observed when we evaluated FGF23 on a continuous scale. Addition of corticosteroid use to the models did not materially change the association (data not shown). Results were also similar in sensitivity analyses excluding black participants or the 668 participants reporting calcium, vitamin D, or bisphosphonate use. Associations of FGF23 with hip fracture risk were also similar irrespective of CKD status when both sexes were evaluated together and in women and men separately (P > .50 for interaction for all; data not shown). Finally, serum calcium, phosphorus, 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25OH)D], and PTH measurements were available in a random subset at the 1997/1998 study visit among 589 women and 388 men. Among this subset, there were 65 hip fractures in women and 21 hip fractures in men during the follow-up period. After multivariable adjustment, the association of FGF23 with hip fracture in women appeared similar in nested models with (HR 0.70; 95% CI 0.44, 1.09) and without (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.47, 1.27) additional adjustment for serum calcium, phosphorus, 25(OH)D, and PTH.

Discussion

Given the known biological effects of phosphaturia and 1,25(OH)2D deficiency induced by higher FGF23 levels, we hypothesized that higher plasma FGF23 concentrations would be associated with lower BMD and greater risk of hip fracture in older persons. However, in this study of 3337 community-dwelling individuals with a long-term follow-up and over 300 hip fractures, we did not observe an association of FGF23 with subsequent hip fracture risk. Moreover, in a subset of participants with BMD data, higher plasma FGF23 concentrations were associated with higher, rather than lower, total hip and lumbar spine BMD in men. These associations had small effect sizes but were meaningful in that they were in the opposite direction from those proposed in our hypothesis. Thus, we found no evidence that FGF23 concentrations are associated with bone disease, either by lower BMD or hip fracture risk, in this large, community-dwelling population of older women and men.

In the Swedish Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study (MrOS), a population-based cohort of 3014 Swedish men aged 69–80 years, Marsell et al (14) examined the relationship between higher serum FGF23 concentrations and BMD. Similar to results shown here, the investigators found a weak direct association between higher FGF23 levels with femoral neck and trochanter, total hip, and lumbar spine BMD, which was independent of biochemical measurements including serum phosphorus, 25(OH)D, intact PTH, and kidney function. The association became nonsignificant after adjusting for age, height, weight, and smoking. In contrast, a study of patients requiring chronic dialysis, a population at high risk of bone disease and fracture, found no association of FGF23 with BMD (26). Our study adds to the existing literature by confirming a weak positive association of FGF23 with BMD in men and by examining the association in older community-dwelling women for the first time. Although FGF23 in animal models and cell culture studies may influence bone mineralization (10–12), collectively, our results along with previous studies suggest that the relationship between FGF23 and BMD is weak or altogether absent in community-dwelling older persons.

To our knowledge, only one previous study has examined the associations of FGF23 with risk of fracture. This study, using the Swedish MrOS cohort, was limited to men, who were predominantly white and had a short follow-up for fracture risk. In contrast to our findings, in the Swedish MrOS cohort, intact FGF23 concentrations in the highest quartile were significantly associated with higher risk of all fractures combined, which included vertebral and hip fractures (15). However, the follow-up was short (3.3 years) and no significant association was observed between higher FGF23 concentrations and hip fracture, specifically. We observed no association with hip fracture in either sex, with much longer follow-up time. Reasons underlying the different findings are uncertain; however, we used the C-terminal FGF23 assay, whereas the MrOS study used a full-length (intact) assay. Although both assays have been associated with progression to end-stage renal disease and mortality in CKD (8, 27), intact FGF23 and C-terminal FGF23 measurements have weaker correlations with each other in healthy individuals and in those with mild to moderate CKD (28). Both measurements are susceptible to proteolytic degradation after 2 hours; however, this effect appears immediately for intact FGF23 (29). Additionally, C-terminal FGF23 measurements were recently found to have less intra-individual variation (28), suggesting that it may be a more precise measurement. Our study, which includes women, a much longer period of follow-up (median 9.6 years), and use of C-terminal FGF23 measurement did not detect an association between higher plasma FGF23 concentrations and hip fractures in either sex. Additionally, the weak but direct association between FGF23 and BMD in men provides additional support that FGF23 is unlikely to be a risk factor for fractures in community-dwelling older populations.

Aside from these differences in methodology, there could be other reasons for the discrepant findings in the current study compared with the Swedish MrOS. The incidence rate of hip fracture in Sweden is among the highest in the world whereas the United States ranks in the middle of industrialized nations (30). This is illustrated in the higher hip fracture incidence (reported as 3.5 per 100 person-years) in the Swedish MrOS study (15) compared with the current study (0.95 per 100 person-years in men), suggesting genetic or socioeconomic differences in these 2 populations. Although the mean age and degree of kidney function was similar in the 2 studies, our participants resided in the United States and were multiracial; however, there were no differences in the final models when black participants were excluded. Dietary intake, lifestyle choices, weight-bearing exercise, vitamin D status, climate, and genetic factors may also have led to discrepant findings between these 2 study samples.

Strengths of this study include the large number of participants, the inclusion of both women and men, the length of follow-up for hip fractures, and the available measures of multiple confounding variables. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the association of higher FGF23 levels with BMD and fracture in community-dwelling women. Despite these and other strengths, our study also has important limitations. First, DXA data were available only in a subset of participants 1.8 ± 0.4 years before FGF23 concentration measurements. However, previous studies demonstrate that BMD is measured with high precision and changes very little over a 2-year period (31). Moreover, the modest, direct association of FGF23 with BMD in men is consistent with previous studies (14). These data suggest that if FGF23 and DXA data were available concurrently, results would not be meaningfully different. Second, hip fracture was obtained through hospital codes, which limits details of each occurrence. Third, plasma FGF23 concentrations, eGFR, and BMD were measured only at single time points; thus, whether trajectories of changing FGF23 and eGFR provide information about changes in BMD or fracture risk remains unknown. Fourth, although our regression models adjusted for many confounding variables, we lacked concurrent measurements of 1,25(OH)2D and alkaline phosphatase concentrations in study participants. Finally, we lack data regarding the use of several medications that could alter fracture risk such as selective estrogen receptor modulators, teriparatide, and calcitonin at baseline or during follow-up.

In conclusion, in community-dwelling older women and men, higher plasma FGF23 concentrations are associated with slightly higher BMD in men only and are not related to an increased risk of hip fracture in either sex. These findings suggest that FGF23 may have little utility as a marker to indentify risk of low bone density or fracture risk in community-dwelling older adults.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (R01HL096851) and American Heart Association (0575021N) to J.H.I. Additionally, this paper was supported in part with resources of the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System. The Cardiovascular Health Study was supported by contract numbers HHSN268201200036C, N01 HC-85079 through N01HC-85086, N01-HC-35129, N01 HC-15103, N01 HC-55222, N01 HC-75150, N01 HC-54133, and N01-HC-80007 and Grant U01 HL080295 from the NHLBI, with additional contributions from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ACR

- albumin-to-creatinine ratio

- BMD

- bone mineral density

- CHS

- Cardiovascular Health Study

- CI

- confidence interval

- CKD

- chronic kidney disease

- 1,25(OH)2D

- 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D

- 25(OH)D

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D

- DXA

- dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- eGFR

- estimated glomerular filtration rate

- FGF23

- fibroblast growth factor 23

- IQR

- interquartile range

- MrOS

- Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study

- PAS

- physical activity score

- RU

- relative units.

References

- 1. Saito H, Maeda A, Ohtomo S, et al. Circulating FGF-23 is regulated by 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and phosphorus in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2543–2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shimada T, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki Y, et al. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:429–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ben-Dov IZ, Galitzer H, Lavi-Moshayoff V, et al. The parathyroid is a target organ for FGF23 in rats. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:4003–4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prié D, Ureña Torres P, Friedlander G. Latest findings in phosphate homeostasis. Kidney Int. 2009;75:882–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gutiérrez OM, Januzzi JL, Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Circulation. 2009;119:2545–2552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;79:1370–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ix JH, Shlipak MG, Wassel CL, Whooley MA. Fibroblast growth factor-23 and early decrements in kidney function: the Heart and Soul Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:993–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Isakova T, Xie H, Yang W, et al. ; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Group Fibroblast growth factor 23 and risks of mortality and end-stage renal disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. JAMA 2011;305:2432–2439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kendrick J, Cheung AK, Kaufman JS, et al. ; HOST Investigators Elevated FGF-23 associates with death, cardiovascular events and initiation of chronic dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011;22:1913–1922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Larsson T, Marsell R, Schipani E, et al. Transgenic mice expressing fibroblast growth factor 23 under the control of the α1(I) collagen promoter exhibit growth retardation, osteomalacia, and disturbed phosphate homeostasis. Endocrinology 2004;145:3087–3094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shimada T, Urakawa I, Yamazaki Y, et al. FGF-23 transgenic mice demonstrate hypophosphatemic rickets with reduced expression of sodium phosphate cotransporter type IIa. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:409–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang H, Yoshiko Y, Yamamoto R, et al. Overexpression of fibroblast growth factor 23 suppresses osteoblast differentiation and matrix mineralization in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:939–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jan de Beur SM. Tumor-induced osteomalacia. JAMA. 2005;294:1260–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marsell R, Mirza MA, Mallmin H, et al. Relation between fibroblast growth factor-23, body weight and bone mineral density in elderly men. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1167–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mirza MA, Karlsson MK, Mellström D, et al. Serum fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23) and fracture risk in elderly men. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:857–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1:263–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fried LF, Biggs ML, Shlipak MG, et al. Association of kidney function with incident hip fracture in older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:282–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jonsson KB, Zahradnik R, Larsson T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 in oncogenic osteomalacia and X-linked hypophosphatemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1656–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robbins J, Hirsch C, Whitmer R, Cauley J, Harris T. The association of bone mineral density and depression in an older population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:732–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Psaty BM, Lee M, Savage PJ, Rutan GH, German PS, Lyles M. Assessing the use of medications in the elderly: methods and initial experience in the Cardiovascular Health Study. The Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:683–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Robinson-Cohen C, Katz R, Mozaffarian D, et al. Physical activity and rapid decline in kidney function among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2116–2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shlipak MG, Sarnak MJ, Katz R, et al. Cystatin C and the risk of death and cardiovascular events among elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2049–2060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stevens LA, Coresh J, Schmid CH, et al. Estimating GFR using serum cystatin C alone and in combination with serum creatinine: a pooled analysis of 3,418 individuals with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:395–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, Johnston CC, Jr, Lindsay R. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of U.S. adults. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:468–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Binkley N, Kiebzak GM, Lewiecki EM, et al. Recalculation of the NHANES database SD improves T-score agreement and reduces osteoporosis prevalence. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ureña Torres P, Friedlander G, de Vernejoul MC, Silve C, Prié D. Bone mass does not correlate with the serum fibroblast growth factor 23 in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2008;73:102–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gutiérrez OM, Mannstadt M, Isakova T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and mortality among patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:584–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smith ER, Cai MM, McMahon LP, Holt SG. Biological variability of plasma intact and c-terminal FGF23 measurements. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3357–3365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Smith ER, Ford ML, Tomlinson LA, et al. Instability of fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23): implications for clinical studies. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412:1008–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cooper C, Cole ZA, Holroyd CR, et al. ; IOF CSA Working Group on Fracture Epidemiology Secular trends in the incidence of hip and other osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1277–1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nelson HD, Helfand M, Woolf SH, Allan JD. Screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:529–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]