Abstract

Background

It has been reported that hyperglycemia can induce endothelial dysfunction via increased oxidative stress and that it plays a central role in the development of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Phyllanthus emblica (Emblica officinalis, amla) is known for its antioxidant and antihyperlipidemic activity. The present study compared the effects of an aqueous extract of P. emblica (highly standardized by high-performance liquid chromatography to contain low molecular weight hydrolyzable tannins, ie, emblicanin A, emblicanin B, pedunculagin, and punigluconin) versus those of atorvastatin and placebo on endothelial dysfunction and biomarkers of oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Eligible patients were randomized to receive either P. emblica 250 mg twice daily, P. emblica 500 mg twice daily, atorvastatin 10 mg in the evening and matching placebo in the morning, or placebo twice daily for 12 weeks. The primary efficacy parameter was the change in endothelial function identified on salbutamol challenge at baseline and after 12 weeks of treatment. Secondary efficacy parameters were changes in biomarkers of oxidative stress (malondialdehyde, nitric oxide, and glutathione), high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels, the lipid profile, and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels. Laboratory safety parameters were measured at baseline and after 12 weeks of treatment.

Results

Eighty patients completed the study. Treatment with P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, or atorvastatin 10 mg produced significant reductions in the reflection index (−2.25%±1.37% to −9.13%±2.56% versus −2.11%±0.98% to −10.04%±0.92% versus −2.68%±1.13% to −11.03%±3.93%, respectively), suggesting improvement in endothelial function after 12 weeks of treatment compared with baseline. There was a significant improvement in biomarkers of oxidative stress and systemic inflammation compared with baseline and placebo. Further, the treatments significantly improved the lipid profile and HbA1c levels compared with baseline and placebo. All treatments were well tolerated.

Conclusion

Both atorvastatin and P. emblica significantly improved endothelial function and reduced biomarkers of oxidative stress and systemic inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, without any significant changes in laboratory safety parameters.

Keywords: Phyllanthus emblica, atorvastatin, endothelial dysfunction, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease accounts for up to 80% of mortality in people with type 2 diabetes. The incidence of mortality attributable to cardiovascular disease is three times higher in individuals with diabetes and a history of myocardial infarction than in nondiabetics.1 A number of risk factors for cardiovascular disease have been identified, including smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, and diabetes mellitus.2 These risk factors cause progressive damage to the vascular wall, manifesting as a low-grade inflammatory process and endothelial dysfunction. Epidemiologic studies show a consistent association between glycemic control and cardiovascular disease.3 Dysfunction of the vascular endothelium is believed to be important in the pathogenesis of microvascular and macrovascular disease.4 Endothelial dysfunction has been the subject of increasing attention in the study of vascular disease. The pathophysiology of endothelial dysfunction is complex and involves multiple mechanisms. One of the most important vasodilating substances released by the endothelium is nitric oxide, which inhibits growth and inflammation, and has an antiaggregating effect on platelets. Reduced nitric oxide levels have been widely reported to be associated with impaired endothelial function. This may result from either reduced activity of nitric oxide synthase and/or decreased bioavailability of nitric oxide.5 Increased production of pathogenic reactive oxygen species, eg, the superoxide anion, is a central abnormality caused by hyperglycemia. Studies show that enhanced generation of reactive oxygen species leads to decreased bioavailability of nitric oxide. Therapies aimed at reducing oxidative stress would benefit patients with type 2 diabetes and those at risk for developing diabetes.5

C-reactive protein is the main inflammatory factor produced by the liver during acute infection or inflammation, and its concentration in plasma can increase by up to 1000fold during injury and infection. C-reactive protein levels are increased in endothelial dysfunction and atherogenesis, and have been associated with macrovascular disease and the nonocular microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes.6–8 C-reactive protein is a predictor of early atherosclerotic damage and is related to increased adiposity (mainly abdominal), insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia.9 C-reactive protein also directly impairs production of nitric oxide, resulting in endothelial dysfunction.10

Many herbs have potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardioprotective properties, and are used by those at increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Amla (Phyllanthus emblica, Emblica officinalis), belonging to the family Euphorbiaceae, is an herbal plant used widely in indigenous medicinal preparations used to treat a variety of diseases. It is also known as the Indian gooseberry or amlaki, and is used in Indian medicine as a cardiotonic.11,12 There is some published evidence that E. officinalis has significant antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic effects in diabetic patients.12 In vitro and animal studies have indicated that E. officinalis has potent antioxidant effects on superoxide and hydroxyl radicals, scavenging activity, and an ability to augment antioxidant enzymes.13 Several clinical trials have shown that 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events in diabetic patients with established coronary artery disease and that they improve endothelial function.14,15 Treatment with low-dose atorvastatin improves endothelial function and reduces the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules in patients with ischemic heart failure.16 The present study evaluated the effect of E. officinalis 250 mg, E. officinalis 500 mg, atorvastatin, and placebo on endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes and investigates the probable mechanism of action of E. officinalis.

Materials and methods

Materials

Quality control is one of the important factors during evaluation of any herbal product. Care needs to be taken to ensure that the bioactive ingredients of the product are intact. The test product used in the present study comprised a highly standardized aqueous extract of E. officinalis (Capros® capsules, Natreon Inc, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), containing not less than 60% of low molecular weight bioactive hydrolyzable tannins (emblicanin A, emblicanin B, pedunculagin, and punigluconin), and not more than 4% of gallic acid. The matching placebo capsules contained microcrystalline cellulose (49.7% w/w), lactose (49.5% w/w), and magnesium stearate (0.69% w/w) as excipients, and were also supplied by Natreon Inc. Atorvastatin 10 mg tablets were obtained from a pharmacy. These tablets were encapsulated into the same type of capsules used for the test products and the placebo, thereby matching the physical appearance of all the products used in the study.

Methods

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study undertaken in the Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics at the Nizam Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad, India, with the approval of the ethics committee at this institution. All subjects gave their written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Men and women aged 30–68 years with a fasting plasma glucose of 110–126 mg/dL, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) 7%–9%, on stable antidiabetic treatment (metformin 1,500–3,000 mg) for the 8 weeks prior to the screening visit, and endothelial function defined as a ≤6% change in reflection index (RI) on salbutamol challenge were included in the study. Patients with severe uncontrolled hyperglycemia, uncontrolled hypertension, cardiac arrhythmia, impaired hepatic or renal function, history of malignancy or stroke, chronic alcoholism or any other serious disease requiring active treatment, concomitant medication known to alter endothelial function, and treatment with any other herbal supplements were excluded from the study. Pregnant and lactating women were also excluded.

All eligible patients were randomized to receive either one capsule of E. officinalis 250 mg twice daily, one capsule of E. officinalis 500 mg twice daily, atorvastatin 10 mg at bed time and matching placebo in the morning daily, or placebo twice daily for 12 weeks as per the prior randomization schedule. Subjects were reviewed after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of therapy. At each visit, they were evaluated for efficacy and safety. Pharmacodynamic evaluation of endothelial function was done at baseline and at the end of 12 weeks of treatment. Blood samples were collected for evaluation of biomarkers at baseline and at the end of treatment. A laboratory safety evaluation, including hematology and hepatic and renal biochemistry, was performed before and at the end of the study, and as needed in the event of an adverse drug reaction. Subjects were asked about the occurrence of adverse events, which were recorded on the case report form. Compliance was assessed by tablet count.

The primary efficacy measure was a change in endothelial dysfunction as reflected by a change in RI compared with baseline at 12 weeks in all the treatment groups. Secondary efficacy measures included changes in markers of oxidative stress and inflammation, the lipid profile, and HbA1c levels after 12 weeks in all the treatment groups.

Assessment of endothelial function

A salbutamol challenge test involving digital volume plethysmography was used to assess endothelial function as per the procedure described by Chowienczyk et al17 and Naidu et al.18 Patients were examined in the supine position after 10 minutes of rest. A digital volume pulse was obtained using a photoplethysmographic pulse tracer (Pulse Trace PCA2, PT200, Micro Medical, Gillingham, Kent, UK) transmitting infrared light at 940 nm, which was placed on the index finger of the right hand. Signals from the plethysmograph were digitized using a 12-bit analog to digital converter at a sampling frequency of 100 Hz. Digital volume pulse waveforms were recorded over a 20-second period, and the height of the late systolic/early diastolic portion of the digital volume pulse was expressed as a percentage of the amplitude of the digital volume pulse to yield the RI, as per the procedure described in detail by Millasseau et al.19 The RI was obtained from the digital volume pulse recording. The mean of three such recordings was considered as the representative value. Patients were then administered 400 μg of salbutamol by inhalation. After 15 minutes, three measurements of RI were obtained and the difference in mean RI before and after administration of salbutamol was used as a measure of endothelial function. A change in RI of ≤6% post salbutamol was considered to indicate endothelial dysfunction.

Evaluation of biomarkers

Serum malondialdehyde,20 nitric oxide,21 and glutathione22 levels were estimated spectrophotometrically and high sensitivity C-reactive protein by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Assessment of pharmacodynamics and safety

A complete physical examination was performed at every visit. Vital parameters, including blood pressure and heart rate, were recorded using a multiparameter Galaxy L&T monitor (Larsen and Toubro Ltd, Mumbai, India) and cardiac output was recorded on a Nivomon L&T monitor (Larsen and Toubro Ltd, Mumbai, India) at baseline and at the end of treatment. Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast of 12 hours for determination of hemoglobin, complete blood profile, HbA1c, blood urea and creatinine, liver function, and lipid profile, all of which were measured using standard techniques. Any change in laboratory safety parameters was investigated and any adverse drug reactions were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The paired t-test was performed within the groups and the unpaired t-test was performed between the groups. P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 4 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Assuming the proportion of subjects achieving improvement in endothelial function while on the test product would be 72% and for atorvastatin would be 90%, a sample size of 80 subjects was calculated to be necessary to provide 80% power in establishing a noninferiority margin of 10% between the groups. Based on these assumptions, a sample size of 20 evaluable subjects per group was required. Taking into account a loss to follow-up of about 10%, 22 subjects were required to be enrolled per group. The subjects needed to be randomized at a ratio of 1:1:1:1. Therefore, a total of 88 subjects needed to be enrolled in the study to ensure 80 evaluable subjects.

Results

Eighty-eight patients were screened and 80 patients completed the study (n=20 in each of the four treatment groups). The patient demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1, and indicate that the study population was homogenous, with no statistically significant differences between the treatment groups with respect to demographic variables.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients in all treatment groups

| Parameter | P. emblica 250 mg | P. emblica 500 mg | Atorvastatin | Placebo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Age, years | 57.60±9.67 | 57.75±9.86 | 56.95±8.04 | 56.90±9.17 |

| gender (M/F) | 13/7 | 15/5 | 13/7 | 12/8 |

| Body weight, kg | 69.30±11.19 | 65.87±7.31 | 68.56±8.47 | 67.42±6.75 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.88±2.76 | 25.22±2.67 | 26.02±3.12 | 24.75±2.41 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; P. emblica, Phyllanthus emblica.

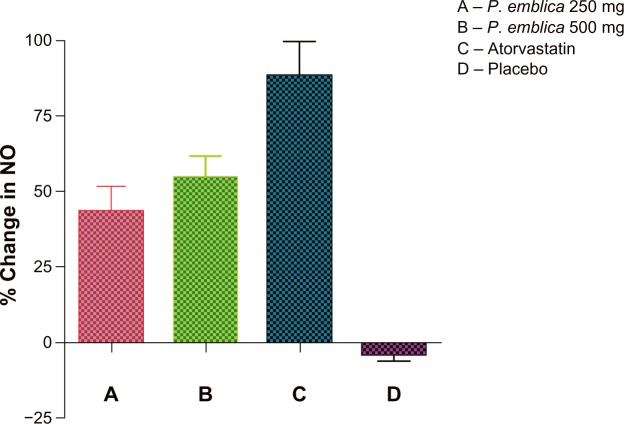

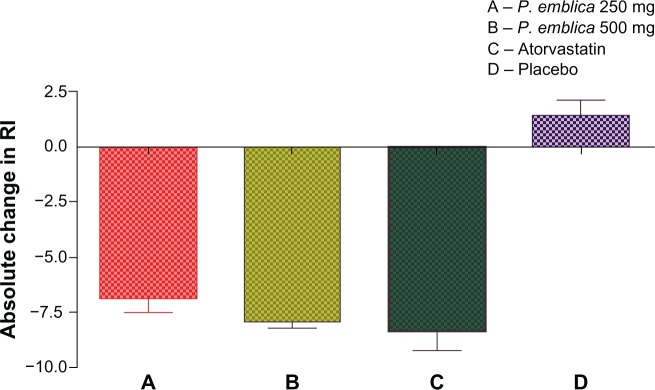

The RI was used to assess endothelial function. Daily treatment with P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, or atorvastatin 10 mg significantly reduced the RI compared with baseline and placebo (Table 2). Further, P. emblica 500 mg and atorvastatin achieved a highly significant improvement in endothelial function compared with P. emblica 250 mg. The mean absolute change in RI was significant for all three active treatments compared with placebo (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Effect of P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, atorvastatin 10 mg, and placebo on RI

| Parameter

|

P. emblica 250 mg twice daily (n=20)

|

P. emblica 500 mg twice daily (n=20)

|

Atorvastatin 10 mg + placebo, each once daily (n=20)

|

Placebo twice daily (n=20)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI (%) | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment |

| Mean | −2.25 | −9.13* | −2.11 | −10.04* | −2.68 | −11.03* | −2.32 | −0.90 |

| SD | ±1.37 | ±2.56 | ±0.98 | ±0.92 | ±1.13 | ±3.93 | ±1.21 | ±2.83 |

Notes:

P<0.001 with all treatments compared to baseline and placebo; nonsignificant in placebo group versus baseline.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; P. emblica, Phyllanthus emblica; RI, reflection index.

Figure 1.

Absolute change in RI after 12 weeks of treatment.

Notes:P<0.001 when compared between A and D, B and D, C and D. Nonsignificant when compared between A and B, A and C, B and C.

Abbreviations: RI, reflection index; P. emblica, Phyllathus emblica.

Malondialdehyde, nitric oxide, and glutathione levels were used to assess oxidative stress. Daily treatment with P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, or atorvastatin siginificantly reduced malondialdehyde levels and increased glutathione levels, suggesting improvement in antioxidant status. Earlier studies have demonstrated that endothelial dysfunction is associated with reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide. Daily treatment with P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, or atorvastatin significantly increased nitric oxide levels compared with baseline and placebo. The effect of the trial medications on biomarkers is shown in Table 3, indicating that P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, and atorvastatin significantly decreased high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels compared with baseline and placebo. Further analysis showed that P. emblica 500 mg and atorvastatin had a better effect than P. emblica 250 mg on all the biomarkers evaluated. Similar changes were also noted with the other biomarkers.

Table 3.

Effect of P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, atorvastatin 10 mg, and placebo on biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation

| Parameter |

P. emblica 250 mg twice daily (n = 20)

|

P. emblica 500 mg twice daily (n = 20)

|

Atorvastatin 10 mg + placebo each once daily (n = 20)

|

Placebo twice daily (n = 20)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

| NO (μM/L) | 32.02±14.81 | 43.31 ±16.99 | 33.27±11.07 | 49.03±11.22 | 35.24±9.71 | 63.69±15.04 | 39.29±8.15 | 37.88±9.22 |

| MDA (nM/mL) | 3.23±1.34 | 2.35±1.00 | 3.35±1.00 | 2.29±0.78 | 3.54±0.85 | 2.37±0.59 | 3.47±0.65 | 3.56±0.52 |

| GSH (μM/L) | 437.71 ±143.2 | 560.2± 169.4 | 405.7± 107.1 | 626.7±143.1 | 418.8± 166.7 | 641.8± 150.2 | 431.8±136.1 | 435.9±128.1 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 2.91±1.53 | 1.59±0.98 | 3.50±1.05 | 1.25±0.42 | 3.08± 1.38 | 0.97±0.78 | 3.09±1.44 | 2.94± 1.47 |

Notes: NO, P<0.001 for B versus A, D versus C, and F versus E; GSH, P<0.001 for B versus A, D versus C, and F versus E; MDA, P<0.001 for B versus A, D versus C, and F versus E; hsCRP, P<0.001 for B versus A, D versus C, and F versus E; in the placebo group, no changes in any of the parameters were statistically significant for G versus H.

Abbreviations: NO, nitric oxide; GSH, glutathione; hsCRP, highly sensitivity C-reactive protein; MDA, malondialdehyde; P. emblica, Phyllathus emblica.

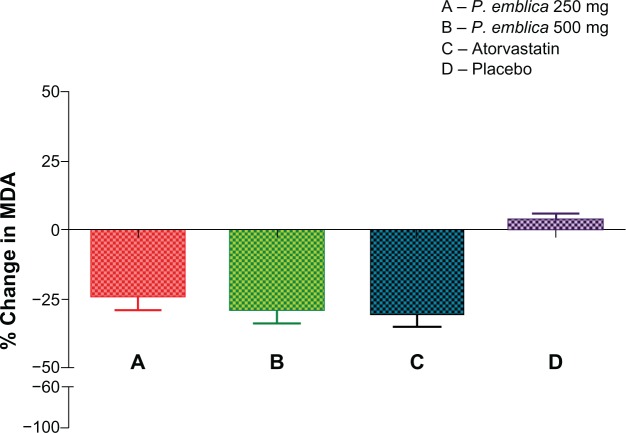

The mean percent change in biomarker values was analyzed for each of the study treatments. The mean reduction in malondialdehyde was 23% in the P. emblica 250 mg group, 28% in the P. emblica 500 mg group, and 30% in the atorvastatin group compared with placebo (Figure 2). As seen in Figure 3, the mean increase in nitric oxide was 43.13% for P. emblica 250 mg, 54.6% for P. emblica 500 mg, and 88% for atorvastatin compared with placebo. The mean increase in glutathione was 30.34%, 61.5%, and 68.4%, respectively, for P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, and atorvastatin compared with placebo (Figure 4). Similarly, P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, and atorvastatin produced a mean decrease in high sensitivity C-reactive protein of 44.56%, 63.16%, and 64.9%, respectively, compared with placebo (Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Mean percent change in NO after 12 weeks of treatment.

Notes:P<0.01 between A and C and P<0.001 between A and D, B and D, and C and D. Nonsignificant when compared between A and B, P<0.005 B and C.

Abbreviations:P. emblica; Phyllathus emblica; NO, nitric oxide.

Figure 3.

Mean percent change in MDA after 12 weeks of treatment.

Notes:P<0.001 when compared between A and D, B and D, and C and D. Nonsignificant when compared between A and B, B and C, and A and C.

Abbreviations:P. emblica, Phyllathus emblica; MDA, malondialdehyde.

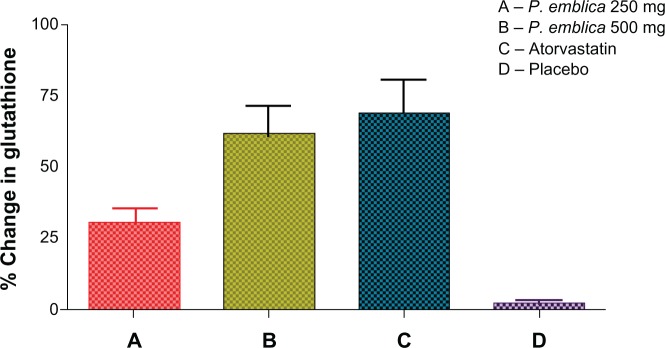

Figure 4.

Mean percent change in gluthathione after 12 weeks of treatment.

Notes:P<0.01 when compared between A and B, and A and C. P<0.001 when compared between A and B, B and D, and C and D. Nonsignificant between B and C.

Abbreviation:P. emblica, Phyllathus emblica.

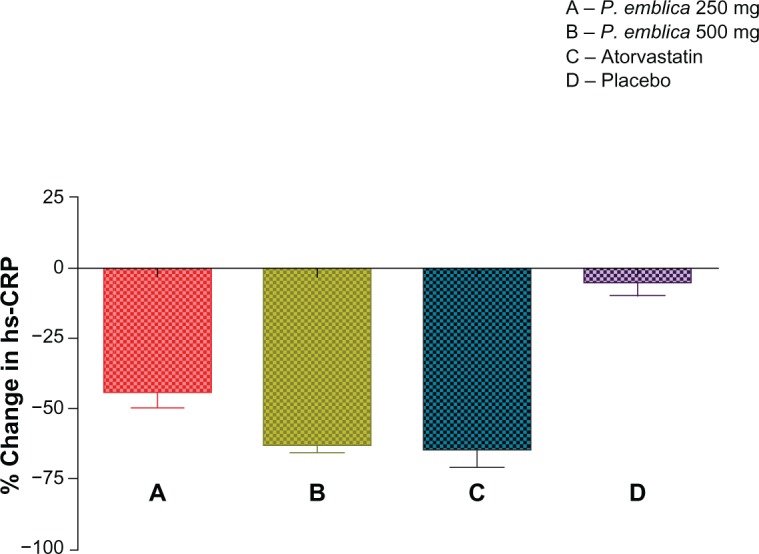

Figure 5.

Mean percent change in hs-CRP after 12 weeks of treatment.

Notes:P<0.01 when compared between A and B. P<0.001 when compared between A and D, B and D, and C and D. P<0.05 between A and C. Nonsignificant between B and C.

Abbreviations: hs-CRP, highly sensitivity C-reactive protein; P. emblica, Phyllathus emblica.

P. emblica is reported to have potent antihyperlipidemic activity. In the present study, we demonstrated its lipid-lowering effect in patients with type 2 diabetes. The results on the lipid profile are shown in Table 4. Treatment with P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, and atorvastatin siginificantly reduced the levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides, and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels compared with baseline and placebo. Compared with placebo, the mean reduction in total cholesterol was 10.89%, 14.3%, and 24.68% on P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, and atorvastatin, respectively, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol decreased by 15.88%, 20.15%, and 35%, respectively. There was a similar mean decrease in triglyceride and very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and a mean increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels by 7.88%, 17.75%, and 21.16% on P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, and atorvastatin, respectively. The effect of the trial medications on HbA1c is shown in Table 5, and all treatments significantly reduced these levels compared with baseline and placebo.

Table 4.

Effect of P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, atorvastatin 10 mg, and placebo on lipid profile

| Parameter |

P. emblica 250 mg twice daily (n=20)

|

P. emblica 500 mg twice daily (n=20)

|

Atorvastatin 10 mg + placebo each once daily (n=20)

|

Placebo twice daily (n=20)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

| TC (mg/dL) | 183.7±30.04 | 161.8±19.81 | 193.2±24.90 | 164.5±22.53 | 183.7±3741 | 135.6±26.94 | 188.9±35.20 | 192.2±32.73 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 39.10±4.12 | 42.10±5.58 | 41.45±6.73 | 47.70±6.17 | 40.44±6.76 | 47.95±5.34 | 38.35±5.21 | 37.50±5.68 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 116.9±28.24 | 95.90±19.43 | 124.3±27.49 | 92.60±25.35 | 126.00±34.90 | 78.50±16.71 | 126.2±39.45 | 135.5±45.27 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 150.8±42.50 | 132.0±39.82 | 164.5±70.54 | 123.8±41.52 | 155.0±56.51 | 106.5±30.79 | 164.3±21.70 | 169.0±19.85 |

| VLDL-C (mg/dL) | 27.25±7.12 | 24.20±5.86 | 31.35±10.58 | 24.45±5.73 | 25.20±6.57 | 19.90±3.64 | 26.40±5.17 | 25.6±4.98 |

Notes: TC, P<0.001 for B versus A, D versus C, and F versus E, P<0.01 for B versus H and D versus H, P<0.001 for F versus H; HDL-C, P<0.01 for B versus A and D versus C, P<0.001 for F versus E, P<0.05 for B versus H, and P<0.001 for D versus H and F versus H; LDL-C, P<0.01 for B versus A and D versus C, P<0.001 for F versus E, P<0.001 for B versus H and D versus H and F versus H; Tg, P<0.01 for B versus A, P<0.001 for D versus C, F versus E, B versus H, D versus H, and F versus H; VLDL-C, P<0.01 for B versus A and D versus C, P<0.001 for F versus E, nonsignificant for B versus H and D versus H, and P<0.001 for F versus H; in the placebo group, no changes in any of the parameters were statistically significant for G versus H.

Abbreviations:P. emblica, Phyllanthus emblica; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; VLDL-C, very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Table 5.

Effect of P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, atorvastatin 10 mg, and placebo on HbA1c levels

| Parameter |

P. emblica 250 mg twice daily (n=20)

|

P. emblica 500 mg twice daily (n=20)

|

Atorvastatin 10 mg + placebo each once daily (n=20)

|

Placebo twice daily (n=20)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | Before treatment | After treatment | |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.79±0.48 | 7.57±0.54 | 7.56±0.5 | 7.09±0.88 | 7.62±0.33 | 6.99±0.39 | 7.64±0.44 | 7.66±0.46 |

Notes:P<0.01 compared between B and A, D and C; P,0.001 between F and E and between F and H; P<0.05 between D and H; nonsignificant when compared between g and H and between B and H.

Abbreviations: HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; P. emblica, Phyllanthus emblica.

There was no significant change in laboratory safety parameters for any of the study treatments compared with baseline. The medications were well tolerated, except for dyspepsia reported by three patients in the P. emblica 500 mg group and headache reported by two patients in the atorvastatin group. None of the subjects discontinued the study prematurely because of these adverse events.

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the effect of P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, atorvastatin, and placebo on endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes. All three active treatments showed a beneficial effect on endothelial function, along with a significant improvement in biomarkers of oxidative stress, including nitric oxide, glutathione, and malondialdehyde. Further, the three active treatments significantly decreased total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, whereas placebo did not have any significant effect on endothelial function or any of the other study parameters. Laboratory safety parameters remained within the normal ranges in all the treatment groups, and no subject discontinued the study due to adverse drug reactions.

Endothelial dysfunction is one of the early prognostic markers of atherosclerosis, and may eventually result in cardiovascular disease. It has been reported that endothelial dysfunction occurs in patients with diabetes much earlier than the clinical manifestations of vascular complications of the disease.15,23 In an earlier study, we reported the presence of endothelial dysfunction assessed by salbutamol challenge indicating a decrease of <6% in RI, which is a marker of endothelial-dependent vasodilatation in diabetic patients.17,18,24 Diabetes is associated with accelerated atherosclerosis and microvascular complications, which are the major causes of morbidity and mortality in those suffering from the disease. Endothelial cell dysfunction is emerging as a key component in the pathophysiology of the cardiovascular abnormalities associated with diabetes mellitus.25 Risk factors such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, smoking, and type 2 diabetes are associated with impaired endothelial function. The intact endothelium promotes vasodilatation principally via the release of nitric oxide, originally known as endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Nitric oxide has been recognized as a key determinant of vascular homeostasis, regulating several physiologic properties, including vascular permeability, and has antithrombotic properties. Decreased production or increased metabolism of nitric oxide may lead to inadequate amounts of nitric oxide within the vasculature and its pathobiologic consequences. The endothelial dysfunction associated with diabetes has been attributed to a lack of bioavailable nitric oxide due to reduced ability to synthesize nitric oxide from L-arginine.26 In the present study, 12 weeks of treatment with P. emblica 250 mg, P. emblica 500 mg, or atorvastatin significantly increased nitric oxide levels in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with placebo. A study in Karachi found that fasting blood sugar and HbA1c levels were significantly elevated whereas serum nitric oxide levels were significantly depressed in normotensive diabetics and hypertensive patients compared with controls.27 However, researchers in Taiwan observed no significant difference in nitric oxide levels in the aqueous humor between any of their diabetic subgroups.28 Prospective studies have established that reduction in bioavailability of nitric oxide is a predictor of dyslipidemia because it is an endogenous and antiatherosclerotic molecule. Several cardiovascular risk factors, including hypercholesterolemia, exert their deleterious effects on the vascular wall via dysfunction in the endothelial L-arginine-nitric oxide pathway.26

Use of herbs by practitioners of Ayurvedic, Chinese, and Unani medicine to manage the cardiovascular complications in diabetic patients has given a new lead in our understanding of the pathophysiology of diabetes. Therefore, it is rational to use our natural resources along with current therapy to identify inexpensive and safer strategies for managing cardiovascular disease.29 Vascular injury in diabetes as a result of hyperglycemia has been associated with oxidative stress. Oxidative stress also plays an important role in the etiology of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease, and is one of the main mechanisms involved in endothelial dysfunction.30 Widespread attention has been focused on the involvement of oxygen free radicals in the pathogenesis of diabetes. Cellular enzymatic (superoxide dismutase) and nonenzymatic (glutathione) antioxidants act as the primary line of defense to counteract the deleterious effects of these free radical species.13 The tannoid principles of P. emblica have been reported to have antioxidant activity in vitro and in vivo. In a study conducted in rats, it was seen that fresh P. emblica juice enriched with emblicanin A and emblicanin B showed antioxidant activity in an ischemia-reperfusion model of oxidative stress in the rat heart.31P. emblica extract and quercetin have also been reported to have cytoprotective effects on account of their antioxidant effects on lipid peroxidation.32 An earlier study by Antony et al also demonstrated the beneficial antioxidant activity of amla fruit on atherosclerosis and dyslipidemia.13

Hypercholesterolemia is a major risk factor for the development of atherosclerosis and is associated with coronary and peripheral vascular disease. Reduction of hypercholesterolemia has been associated with improvement of coronary artery disease, and intensive interventions, including diet, exercise, and use of antihypercholesterolemic and anti-inflammatory drugs, are recommended. However, some patients cannot tolerate the adverse effects of these drugs, necessitating the use of safer therapeutic alternatives.33 For example, the side effects of statins include hepatotoxicity and myopathy, so the US Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning on the labeling of these agents. In the present study, we found that 12 weeks of treatment with P. emblica and atorvastatin achieved a significant improvement in the lipid profile. There were no serious side effects, with either treatments necessitating discontinuation of treatment. This may have been because of the small number of subjects included in the study.

Natural polyphenols, eg, flavonoids and tannic acid (in particular, hydrolyzable tannins), are reported to have a favorable effect on the plasma lipid profile in patients with coronary heart disease. The amla fruit (the natural form of P. emblica) contains high amounts of vitamin C, as well as cytokine-like substances (identified as zeatin, Z-riboside, and Z-nucleotide), flavonoids, pectin, and tannins. The tannins present in amla delay the oxidation of vitamin C, while pectin has been reported to decrease serum cholesterol levels in humans.34

In another study, the flavonoid content of amla was analyzed for its biological activity and found to have a potent hypolipidemic effect.35 Akhtar et al evaluated the antihyper-glycemic and lipid-lowering properties of amla in healthy volunteers and diabetic patients.12 Significant decreases in total cholesterol and triglycerides and improvement in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were observed in both normal volunteers and diabetic subjects receiving 2–3 g of P. emblica powder per day. In their study of P. emblica, Antony et al12 also reported a significant reduction in total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides, as well as a significant elevation of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Although the exact mechanism by which amla exerts this beneficial effect is presently not clear, it seems likely that it brings about favorable changes in the lipid profile via several mechanisms, including interference with cholesterol absorption,32 inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase activity, and an increase in lecithin cholesterol acyl transferase activity.34

C-reactive protein is a sensitive marker for systemic inflammation. A relationship between inflammation and development of atherosclerotic disease, in particular coronary heart disease, has recently been demonstrated in epidemiologic studies. However, it is unclear whether elevated C-reactive protein levels are merely a phenomenon accompanying atherosclerosis or if C-reactive protein itself is involved in the initiation and/or progression of atherosclerosis.35 The metabolic syndrome is known to be associated with a greatly increased risk of coronary artery disease. Previous research suggests a positive relationship between components of the metabolic syndrome and markers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study,36 in which there was a positive link found between systemic inflammation and the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its cardiovascular complications. Therefore, inflammation could be an important pathophysiologic link between the metabolic syndrome and coronary artery disease.37 In our study, 12 weeks of treatment with P. emblica or atorvastatin significantly reduced high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels, suggesting that both medications probably exert their beneficial effects via reducing systemic inflammation and acting as oxygen free radical scavengers, thereby improving endothelial function.

Conclusion

Impaired endothelial function in type 2 diabetes mellitus may be due to reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide and increased oxidative stress. In the present study, atorvastatin and a proprietary P. emblica extract containing emblicanin A, emblicanin B, pedunculagin, and punigluconin as bioactives achieved significant improvement in endothelial function and a reduction in biomarkers of oxidative stress and systemic inflammation. Addition of P. emblica to the currently available antihyperlipidemic agents may augment the activity of the statins and offer significant protection against atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. It can be concluded from our study that P. emblica extract may be a good therapeutic alternative to statins in diabetic patients with endothelial dysfunction because it has the beneficial effects of the statins but without the well known adverse effects of these agents, including myopathy, hepatic dysfunction, and headache. However, extensive clinical studies are required in larger numbers of patients to establish the efficacy and safety of P. emblica in the management of endothelial dysfunction and hyperlipidemia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Natreon Inc for providing the proprietary extract of P. emblica, atorvastatin, and placebo used in this study, kits for biomarker estimation, and relevant literature. The authors thank Dr Sravanthi, Ayurvedic physician, for her expert advice.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Sowers James R, Epstein M, Frohlich ED. Diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease. An update. Hypertension. 2001;37:1053–1059. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.4.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winner N, Sowers JR. Epidemiology of diabetes. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:397–405. doi: 10.1177/0091270004263017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balkau B, Hu G, Qiao Q, Tuomilehto J, Borch-Johnsen K, Pyorala K. Prediction of the risk of cardiovascular mortality using a score that includes glucose as a risk factor: the DECODE Study. Diabetologia. 2004;47:2118–2128. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1574-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stehouwer CD, Lambert J, Donker AJ, Hinsbergh VW. Endothelial dysfunction and pathogenesis of diabetic angiopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;34:55–68. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright E, Jr, Scism-Bacon JL, Glass LC. Oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes: the role of fasting and postprandial glycaemia. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:308–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stehouwer CD, Gall MA, Twisk JW, Knudsen E, Emeis JJ, Parving HH. Increased urinary albumin excretion, endothelial dysfunction, and chronic low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes: progressive, interrelated, and independently associated with risk of death. Diabetes. 2002;51:1157–1165. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lapice E, Maione S, Patti L, et al. Abdominal adiposity is associated with elevated C-reactive protein independent of BMI in healthy nonobese people. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1734–1736. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabay C, Kushner I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:448–454. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahat K, Chatwal S, Arora S, et al. Antihyperglycemic, antihyperlipidemic, anti-inflammatory and adenosine deaminase-lowering effects of garlic in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:50–56. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S38888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antony B, Merina B, Sheeba V, Mukkadan J. Effect of standardized Amla extract on atherosclerosis and dyslipidemia. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2006;68:437–441. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akhtar MS, Ramzan A, Ali A, Ahmad M. Effect of amla fruit (Emblica officinalis Gaertn.) on blood glucose and lipid profile of normal subjects and type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2011;62:606–616. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2011.560565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antony B, Benny M, Kaimal TN. A pilot clinical study to evaluate the effect of Emblica officinalis extract (Amlamax™) on markers of systemic inflammation and dyslipidemia. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2008;23:378–381. doi: 10.1007/s12291-008-0083-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pyorala K, Pedersen TR, Kjekshus J, Faergeman O, Olsson AG, Thorgeirsson G. Cholesterol lowering with simavastatin improves prognosis of diabetic patients with coronary heart disease: a subgroup analysis of the Scandinavian Simavastatin Survival Study(4S) Diabetes Care. 1997;20:614–620. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tantikosoom W, Thinkhamrop B, Songsak K, Jarernsiripornkul N, Srinakarin J, Ojongpianl S. Randomized trial of Atorvastatin in improving endothelial function in diabetics without prior coronary disease and having average cholesterol level. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tousoulis D, Antoniades C, Vassiliadou C, et al. Effects of combined administration of low dose atorvastatin and vitamin E on inflammatory markers and endothelial function in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Failure. 2005;7:1126–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chowienezyk PJ, Kelly RP, MacCallum H, et al. Photoplethysmographic assessment of pulse wave reflection: blunted response to endothelium dependent beta2-adrenergic vasodilation in type II diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:2007–2014. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naidu MUR, Sridhar Y, UshaRani P, Mateen AA. Comparison of two β2 adrenoceptor agonists by different routes of administration to assess human endothelial function. Indian J Pharmacol. 2007;39:168–169. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Millaesseau SC, Kelly RP, Ritter JM, Chowienczyk PJ. Determination of age related increases in large artery stiffness by digital pulse contour analysis. Clin Sci. 2002;103:371–377. doi: 10.1042/cs1030371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vidyasagar J, Karunaka N, Reddy MS, Rajnarayan K, Surender T, Krishna DR. Oxidative stress and antioxidant status in acute organophosphorous insecticide poisoning. Indian J Pharmacol. 2004;36:76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katrina MM, Michael GE, David AW. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Biol Chem. 2001;5:62–71. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CDA. Vascular complications in diabetes mellitus: the role of endothelial dysfunction. Clin Sci. 2005;109:143–159. doi: 10.1042/CS20050025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Usharani P, Mateen AA, Naidu MU, Raju YS, Chandra N. Effect of NCB-02, atorvastatin and placebo on endothelial function, oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, 8-week study. Drugs R D. 2008;9:243–250. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200809040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Assunta P, Elena A. Chronic hyperglycemia and nitric oxide bioavailiability play a pivotal role in pro-atherogenic vascular modifications. Genes Nutr. 2007;17:195–208. doi: 10.1007/s12263-007-0050-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duncan B, Meeking D, Kenneth S, Cummings M. Endothelial dysfunction and pre-symptomatic atherosclerosis in type 1 diabetes – pathogenesis and identification. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2003;3:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahid SM, Mahboob T. Diabetes and hypertension: correlation between glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and serum nitric oxide (NO) Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2009;3:1323–1327. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsai DC, Chiou SH, Lee FL, Peng CH, Kuo YH, Chen CF. Possible involvement of nitric oxide in the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 2003;217:342–346. doi: 10.1159/000071349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel SS, Goyal RK. Emblica officinalis Geart. A comprehensive review on phytochemistry, pharmacology and ethnomedicinal uses. Research Journal of Medicinal Plants. 2012;6(1):6–16. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ceriello A, Assaloni R, Da Ros R, et al. Effect of atorvastatin and irbesartan, alone and in combination, on postprandial endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation in type 2 diabetic patients. Circulation. 2005;111:2518–2524. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000165070.46111.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharya SK, Bhattacharya A, Sairam K, Ghosal S. Effect of bioactive tannoid principles of Emblica officinalis on ischemia-reperfusion-induced oxidative stress in rat heart. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:171–174. doi: 10.1078/0944-7113-00090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathur R, Sharma A, Dixit VP, Varma M. Hypolipidemic effect of fruit juice of Emblica officinalis in cholesterol-fed rabbits. J Ethnopharmacol. 1996;50:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(95)01308-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suanarunsawat T, Devakul Na Ayutthaya W, Songsak T, Thirawarapan S, Poungshompoo S. Antioxidant activity and lipid-lowering effect of essential oils extracted from Ocimum sanctum leaves in rats fed with a high cholesterol diet. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2010;1:52–59. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.09-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhattacharya A, Chatterjee A, Ghoshal S, Bhattacharya SK. Antioxidant activity of active tannoid principle of Emblica officinalis (Amla) Indian J Exp Biol. 2000;37:676–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anila L, Vijyalaxmi NR. Flavanoids from Emblica officinalis and Magnifera indica. Effectiveness for dyslipidemia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;79:81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00361-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koenig W, Sund M, Frohlich M, et al. C-reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men. Circulation. 1999;99:237–242. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tajiri Y, Mimura K, Umeda F. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Obes Res. 2005;13:1810–1816. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]