Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials of amantadine for the treatment of olanzapine-induced weight gain.

Methods:

Studies were identified using online searches of PUBMED/MEDLINE and Cochrane database (CENTRAL), along with websites recording trial information such as ClinicalTrials.gov, Controlled-trials.com, and Clinicalstudyresults.org. Study eligibility criteria included randomized, double-blind clinical trials comparing amantadine with placebo for olanzapine-induced weight gain with body weight as an outcome measure and study duration of at least 12 weeks. The methodological quality of included trials was assessed using the Jadad Scale. Separate meta-analyses were undertaken for each outcome (body weight and frequency of weight loss >7%) and treatment effects were expressed as weighted mean differences (WMD) and Mantel–Haenszel odds ratio for continuous and categorical outcomes, respectively.

Results:

A systematic review of literature revealed six studies that had assessed amantadine for olanzapine-induced weight gain. Of these, two studies (n = 144) met the review inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis. Meta-analysis was performed to see the effect size of the treatment on body weight and frequency of body weight loss >7%. For body weight change, WMD was −1.85 (95% confidence interval [CI] −3.31 to −0.39) kg with amantadine as compared with placebo; the overall effect was statistically significant (p = 0.01). For frequency of body weight loss >7%, Mantel–Haenszel odds ratio for weight loss was 3.72 (95% CI 1.19–11.62), favoring amantadine as compared with placebo, and the overall effect was significant (p = 0.02).

Conclusions:

Existing data is limited to two studies, which support the efficacy of amantadine for olanzapine-induced weight gain and a significant proportion of patients might lose weight with amantadine compared with placebo.

Keywords: amantadine, olanzapine, meta-analysis, systematic review, weight gain

Introduction

Body weight gain and metabolic alterations are clinically relevant side effects of atypical antipsychotics, specifically olanzapine and clozapine, which is evident at approximately 10 weeks of treatment [Allison et al. 1999; Sussman, 2001; Komossa et al. 2010] and appears to be dose related [Simon et al. 2009]. Olanzapine, in particular, is linked to clinically significant body weight gain ranging from 0.9 kg/month to up to 6–10 kg or more after 1 year of treatment [Nemeroff, 1997]. In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, 30% of olanzapine-treated patients gained >7% of their baseline body weight [Lieberman et al. 2005]. Therefore, effective pharmacological and nonpharmacological strategies are urgently required for optimal body weight control during olanzapine treatment [Faulkner et al. 2007]. Several medications such as amantadine, nizatidine, ranitidine, famotidine, topiramate, fenfluramine, reboxetine, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sibutramine, dextroamphetamine, d-fenfluramine, orlistat, phenylpropanolamine, rosiglitazone, and metformin have been trialed and have been reported to effectively prevent and reduce antipsychotic-induced body weight gain [Faulkner and Cohn, 2006; Baptista et al. 2008; Maayan et al. 2010].

Although the mechanism for olanzapine-induced weight gain is not known, appetite stimulation and insulin resistance are possible factors associated [Henderson et al. 2005; Kluge et al. 2007]. Appetite stimulation has been suggested to involve serotonin 5HT2C and histamine H1 receptor antagonism, resulting in food craving and binge eating [Stahl, 1998]. Amantadine is an antiviral agent effective against influenza A infection [Jefferson et al. 2006] as well as an antiparkinsonian drug used for the treatment of extrapyramidal side effects associated with antipsychotic drugs [Silver and Geraisy, 1996]. It has been studied for weight reducing effects in those with antipsychotic-induced weight gain, based on its ability to modify dopamine and serotonin neurotransmission. In an animal study, there was dose-dependent appetite loss following administration of amantadine through the lateral hypothalamus, possibly through release of dopamine and serotonin in the nucleus accumbens and lateral hypothalamus [Baptista et al. 1997], although it failed to prevent sulpiride-induced weight gain completely. As the weight gain pattern is different for olanzapine as compared with other atypical antipsychotics and it is one of the most commonly used antipsychotics, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis with an objective to determine the effects of amantadine for reducing or preventing weight gain associated with olanzapine.

Methods

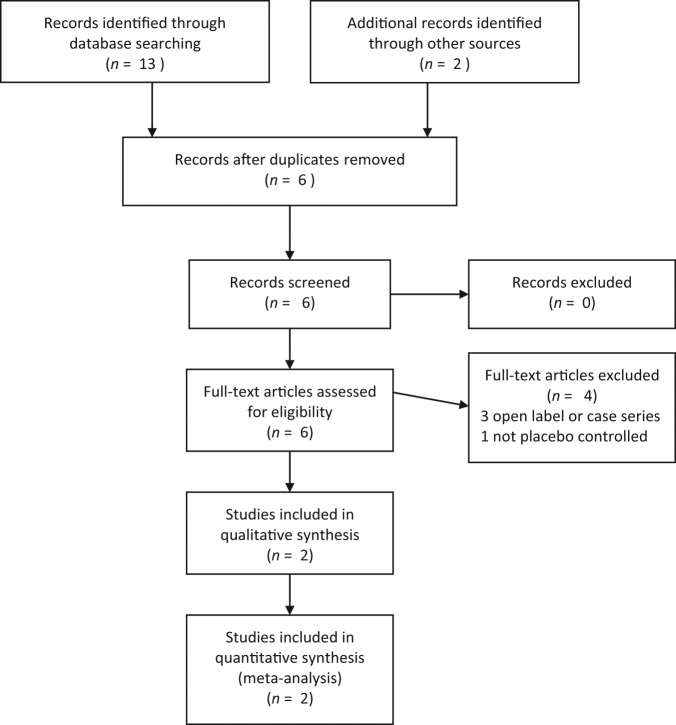

In our systematic review and meta-analysis, we adhered to the recent update of preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Moher et al. 2009]. The flow of studies is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Data sources and search strategy

Studies were identified using online searches of PUBMED/MEDLINE and the Cochrane database (CENTRAL). Also, websites recording trial information such as ClinicalTrials.gov, Controlled-trials.com, and Clinicalstudyresults.org were searched for relevant studies. Searches were conducted using combination of terms ‘atypical antipsychotics’, ‘olanzapine’, ‘body weight gain’, ‘obesity’ and ‘amantadine’. We inspected reference list of all identified studies, including existing reviews for relevant citations. The search was restricted to publications in the English language.

Study selection: inclusion criteria

One reviewer (SKP) initially evaluated the abstracts from the literature search. The following criterion was used to identify the studies:

randomized, double-blind clinical trials comparing amantadine with placebo for olanzapine-induced weight gain;

outcome measures include body weight;

study duration of at least 12 weeks.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (SKP and PSVNS) decided, independently, whether individual studies met the inclusion criteria. We used a standardized form, and extracted data which included patient and study characteristics, outcome measures and study results.

Assessment of methodological quality of studies

The methodological quality of included trials in this review was assessed using the Jadad scale [Jadad et al. 1996]. It includes three items:

Was the study described as randomized?

Was the study described as double-blind?

Was there a description of withdrawals and drop outs?

Scoring was done as follows: one point for positive answer and one point deducted if either the randomization or the blinding/masking procedures are inadequate. Cut-off of two points on the Jadad scale was considered.

Quantitative data synthesis

Meta-analyses were undertaken to estimate overall treatment effects where the trials were considered to be similar enough to combine using RevMan 5 version. This decision was based on assessing similarity of trial characteristics as well as results. Separate meta-analyses were undertaken for each outcome (body weight and frequency of weight loss >7%). Treatment effects were expressed as weighted mean differences (WMD) for continuous outcomes with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For categorical outcome, Mantel–Haenszel odds ratio (with 95% CI) was obtained. Homogeneity among studies was tested using Cochran’s Q test and I 2 statistic, in which greater than 50% indicates a moderate amount of heterogeneity [Higgins et al. 2003]. If significant statistical heterogeneity was detected (Cochran Q test p < 0.1 or I 2 value >50%), random effects estimates were calculated. Otherwise, a fixed-effect model was used for analysis.

Results

Studies included

The combined search strategies identified six papers on the use of amantadine in olanzapine-induced weight gain after removing duplications. Three studies [Floris et al. 2001; Gracious et al. 2002; Bahk et al. 2004] were excluded as they were open-label studies or case series. The Eli Lilly study was excluded as it was not placebo-controlled [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00401973]. Finally, two studies [Deberdt et al. 2005; Graham et al. 2005] met the review inclusion criteria (total 144 subjects) and were included in the final analysis. Characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1. In the study by Deberdt and colleagues, 16-week values were included in the meta-analysis [Deberdt et al. 2005].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Methods | Participants | Intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deberdt et al. [2005] | Allocation: randomized Blinding: double Duration: 16 weeks (+8 weeks) |

Diagnosis: schizophrenia, schizoaffective, schizophreniform and bipolar I disorder N = 125 |

1. Olanzapine 5–20 mg plus amantadine 100–300 mg daily. N = 60 2. Olanzapine 5–20 mg plus placebo. N = 65 |

Body weight, BMI, BPRS, MADRS, lipid profile, leptins, insulin, fructosamine, prolactin |

| Graham et al. [2005] | Allocation: randomized Blinding: double Duration: 12 weeks |

Diagnosis: schizophrenia, schizoaffective and bipolar disorder N = 21 |

1. Olanzapine 5–30 plus amantadine up to 300 mg daily. N = 12 2. Olanzapine 5–30 mg plus placebo. N = 9 |

Body weight, BMI, PANSS, glucose, insulin, prolactin, lipid profile |

BMI, body mass index; BPRS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

Study quality

Both of the studies [Deberdt et al. 2005; Graham et al. 2005] were described as randomized and were double blind. Dropout rates were mentioned in both of the studies, and it varied from 11.2% to 14.2%. Concealment of allocation was not adequately reported in both the studies. Therefore, as it was unclear how randomization sequences were kept concealed, it is likely that the studies are prone to at least a moderate degree of bias [Juni et al. 2001].

Meta-analysis

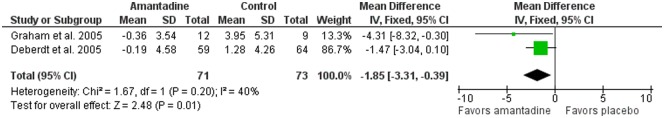

Forest plots for meta-analyses for body weight and frequency of weight loss >7% are presented in Figures 2 and 3. For body weight change, the test for heterogeneity was not significant (p = 0.20, I 2 = 40%); therefore, a fixed-effects model was used. Weighted mean difference for body weight change was −1.85 (95% CI −3.31 to −0.39) kg with amantadine as compared with placebo; the overall effect was statistically significant (p = 0.01).

Figure 2.

Forest plot showing body weight change (kg) at 12 weeks in randomized controlled trials comparing amantadine and placebo for olanzapine-induced weight gain (N = 144).

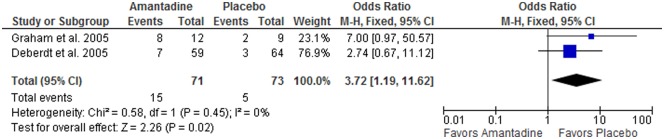

Figure 3.

Forest plot showing the frequency of weight loss (>7%) at 12 weeks in randomized controlled trials comparing amantadine and placebo for olanzapine-induced weight gain (N = 144).

For, frequency of body weight loss >7% (N = 144), the test for heterogeneity was not significant (p = 0.45, I 2 = 0%) and the fixed-effects model was used. The Mantel–Haenszel odds ratio for weight loss was 3.72 (95% CI 1.19–11.62), favoring amantadine as compared with placebo, and the overall effect was significant (p = 0.02).

Discussion

Existing data shows that the weight mitigating effect of amantadine at doses of 100–300 mg per day was statistically significant as compared with placebo in patients with olanzapine-induced weight gain, although the results are based on a small sample (N = 144). In these studies, amantadine was well tolerated with some adverse effects, such as insomnia and upper abdominal discomfort were significantly higher than placebo. There is no evidence of worsening of symptoms after the addition of amantadine. Nevertheless, these data may not be sufficient to recommend routine use of amantadine for the treatment of olanzapine-induced weight gain.

It is interesting to note that odds of significant weight loss (>7% initial body weight) was higher in those receiving amantadine (odds ratio [OR] 3.72, 95% CI 1.19–11.62) as compared with the placebo group. It appears that a subset of patients might have benefited from treatment with amantadine. In a recent post hoc analysis of studies evaluating weight-reducing agents (nizatidine, amantadine and sibutramine) as adjunctive treatment to olanzapine therapy, it was observed that these medications do not benefit all patients, but might have therapeutic potential for some patients [Stauffer et al. 2009]. In future, prospective studies are required for identification of these subsets of patients who will benefit from such treatments.

Furthermore, the search for genetic mechanisms underlying the drug response in antipsychotic-induced metabolic dysfunction is important. Preliminary results have shown that leptin tended to increase after placebo whereas there was a small nonsignificant reduction after metformin, in spite of similar weight gain suggests a beneficial effect of this antidiabetic agent in olanzapine-induced weight gain [Baptista et al. 2007]. In another study by Fernandez and colleagues, specific genetic polymorphism of leptin gene showed a blunted response to metformin in clozapine-treated patients [Fernández et al. 2010]. Such pharmacogenetic studies will identify specific subsets of patients who will benefit from treatment with anti-obesity medications during antipsychotic treatment.

Our review is limited by the number of studies included for meta-analysis. Fewer studies did not allow us to conduct tests for publication bias. Also, sensitivity analysis was not performed in our study. Heterogeneity was absent for body weight change and frequency of weight loss; therefore, a fixed effects model was used. In both of the studies, subjects had gained weight following olanzapine treatment; in the study by Graham and colleagues, a minimum weight gain of 5 lbs was required [Graham et al. 2005]; whereas, in the study by Derberdt and colleagues, subjects gained 5% or more of their baseline weight [Derberdt et al. 2005]. It has been observed that reversal of weight gain is a less effective strategy than the prevention of weight gain, therefore medications to counter weight gain need to be started early in the course of treatment [Hasnain et al. 2010]. Both of the studies did not address the possibility of prevention of weight gain with the addition of amantadine along with initiation of olanzapine treatment. Therefore, in future studies prevention of weight gain needs to be assessed.

We also suggest that all future studies should respect standards of measuring outcomes and of reporting data in order to enhance the comparability of study results. Also, binary outcomes (number of patients losing >7% initial body weight) should be reported as they are easier to interpret and clinically relevant. Such outcome measures may reveal significantly different results, as observed in our meta-analysis. Details regarding the allocation sequence and allocation concealment should be clearly described in all of the studies to prevent bias.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Contributor Information

Samir Kumar Praharaj, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka 576104, India.

Podila Satya Venkata Narasimha Sharma, Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka, India – 576104.

References

- Allison D.B., Mentore J.L., Heo M., Chandler L.P., Cappelleri J.C., Infante M.C., et al. (1999) Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry 156: 1686–1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahk W.M., Lee K.U., Chae J.H., Pae C.U., Jun T., Kim K.S. (2004) Open label study of the effect of amantadine on weight gain induced by olanzapine. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 58: 163–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista T., ElFakih Y., Uzcátegui E., Sandia I., Tálamo E., Araujo de Baptista E., et al. (2008) Pharmacological management of atypical antipsychotic-induced weight gain. CNS Drugs 22: 477–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista T., López M.E., Teneud L., Contreras Q., Alastre T., de Quijada M., et al. (1997) Amantadine in the treatment of neuroleptic-induced obesity in rats: behavioral, endocrine and neurochemical correlates. Pharmacopsychiatry 30: 43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptista T., Sandia I., Lacruz A., Rangel N., de Mendoza S., Beaulieu S., et al. (2007) Insulin counter-regulatory factors, fibrinogen and C-reactive protein during olanzapine administration: effects of the antidiabetic metformin. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 22: 69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deberdt W., Winokur A., Cavazzoni P.A., Trzaskoma Q.N., Carlson C.D., Bymaster F.P., et al. (2005) Amantadine for weight gain associated with olanzapine treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 15: 13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G., Cohn T.A. (2006) Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic strategies for weight gain and metabolic disturbance in patients treated with antipsychotic medications. Can J Psychiatry 51: 502–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G., Cohn T., Remington G. (2007) Interventions to reduce weight gain in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 33: 654–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández E., Carrizo E., Fernández V., Connell L., Sandia I., Prieto D., et al. (2010) Polymorphisms of the LEP- and LEPR genes, metabolic profile after prolonged clozapine administration and response to the antidiabetic metformin. Schizophr Res 121: 213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floris M., Lejeune J., Deberdt W. (2001) Effect of amantadine on weight gain during olanzapine treatment. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 11: 181–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracious B.L., Krysiak T.E., Youngstrom E.A. (2002) Amantadine treatment of psychotropic-induced weight gain in children and adolescents: case series. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 12: 249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K.A., Gu H., Lieberman J.A., Harp J.B., Perkins D.O. (2005) Double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of amantadine for weight loss in subjects who gained weight with olanzapine. Am J Psychiatry 162: 1744–1746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain M., Vieweg W.V., Fredrickson S.K. (2010) Metformin for atypical antipsychotic-induced weight gain and glucose metabolism dysregulation: review of the literature and clinical suggestions. CNS Drugs 24: 193–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson D.C., Cagliero E., Copeland P.M., Borba C.P., Evins E., Hayden D., et al. (2005) Glucose metabolism in patients with schizophrenia treated with atypical antipsychotic agents: a frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test and minimal modal analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62: 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327: 557–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadad A.R., Moore R.A., Carroll D., Jenkinson C., Reynolds D.J., Gavaghan D.J., et al. (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson T., Demicheli V., Di Pietrantonj C., Rivetti D. (2006) Amantadine and rimantadine for influenza A in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2: CD001169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juni P., Altman D.G., Egger M. (2001) Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ 323: 42–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge M., Schuld A., Himmerich H., Dalal M., Schacht A., Wehmeier P.M., et al. (2007) Clozapine and olanzapine are associated with food craving and binge eating: results from a randomized double blind study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 27: 662–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komossa K., Rummel-Kluge C., Hunger H., Schmid F., Schwarz S., Duggan L., et al. (2010) Olanzapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3: CD006654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman J.A., Stroup T.S., McEvoy J.P., Swartz M.S., Rosenheck R.A., Perkins D.O., et al. ; Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators (2005) Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 353: 1209–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maayan L., Vakhrusheva J., Correll C.U. (2010) Effectiveness of medications used to attenuate antipsychotic-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 1520-1530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., for the The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeroff C.B. (1997) Dosing the antipsychotic medication olanzapine. J Clin Psychiatry 58: 45–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver H., Geraisy N. (1996) Amantadine does not exacerbate positive symptoms in medicated, chronic schizophrenic patients: evidence from a double-blind crossover study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 16: 463–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon V., van Winkel R., De Hert M. (2009) Are weight gain and metabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotics dose dependent? A literature review. J Clin Psychiatry 70: 1041–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl S.M. (1998) Neuropharmacology of obesity: my receptors make me eat. J Clin Psychiatry 59: 447–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer V.L., Lipkovich I., Hoffmann V.P., Heinloth A.N., McGregor H.S., Kinon B.J. (2009) Predictors and correlates for weight changes in patients co-treated with olanzapine and weight mitigating agents; a post-hoc analysis. BMC Psychiatry 9: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman N. (2001) Review of atypical antipsychotics and weight gain. J Clin Psychiatry 62: 5–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]