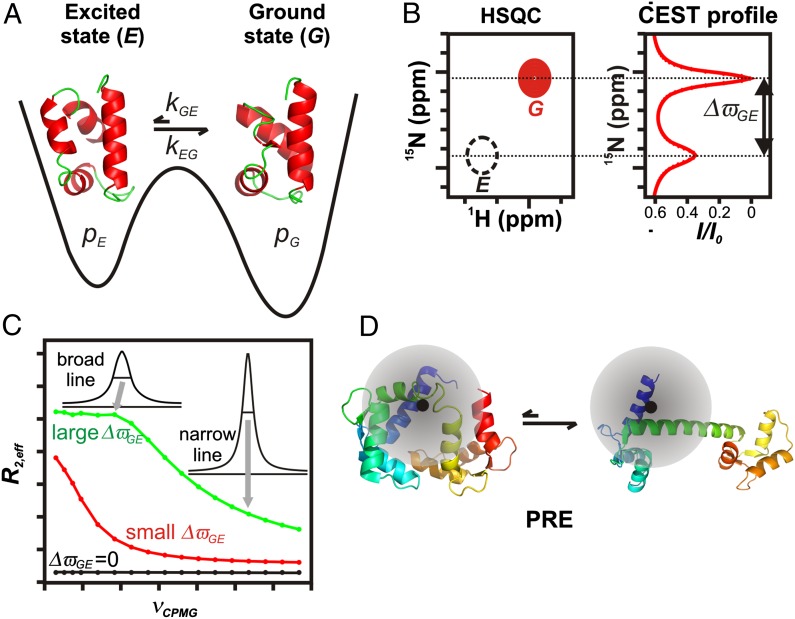

Fig. 1.

NMR methods for studying sparsely populated, transiently formed biomolecular conformers. (A) Schematic 1D energy landscape showing the ground state of a protein in exchange with a thermally accessible excited state. Exchange between G and E is in the microsecond-to-millisecond regime, with pE << pG. (B) Schematic (Left) showing a small region from a standard 15N-1H Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence dataset. The peak derived from state E (dashed black) is not visible in a typical spectrum and is shown here only for clarity. The CEST profile (Right) is obtained by varying the 15N frequency of a weak radio frequency (B1) field. Reduction in resonance intensity (I/I0) of the ground-state peak is seen when irradiation frequencies correspond to resonance positions of G or E. Consequently, ΔϖGE can be readily obtained from the CEST profile. (C) CPMG RD profiles, R2,eff vs. νCPMG, for different ΔϖGE values (0 ppm, black; 1.7 ppm, red; 6.8 ppm, green). Values of R2,eff are calculated from intensities of correlations derived from the ground state as a function of pulsing frequency. Higher pulsing frequencies more effectively refocus the dephasing (excess peak line width) arising from exchange, resulting in narrower peaks and smaller R2,eff values. CPMG dispersion profiles can be fit to extract ΔϖGE values and exchange parameters. (D) Cartoon representation of a protein labeled with a paramagnetic spin label (black) that exchanges between a ground-state conformation and a compact excited state. The shaded circle represents the sphere of influence of the spin label. The regions of the protein that are proximal to the unpaired electron, and, hence the pattern of PREs, are clearly different in the two states.