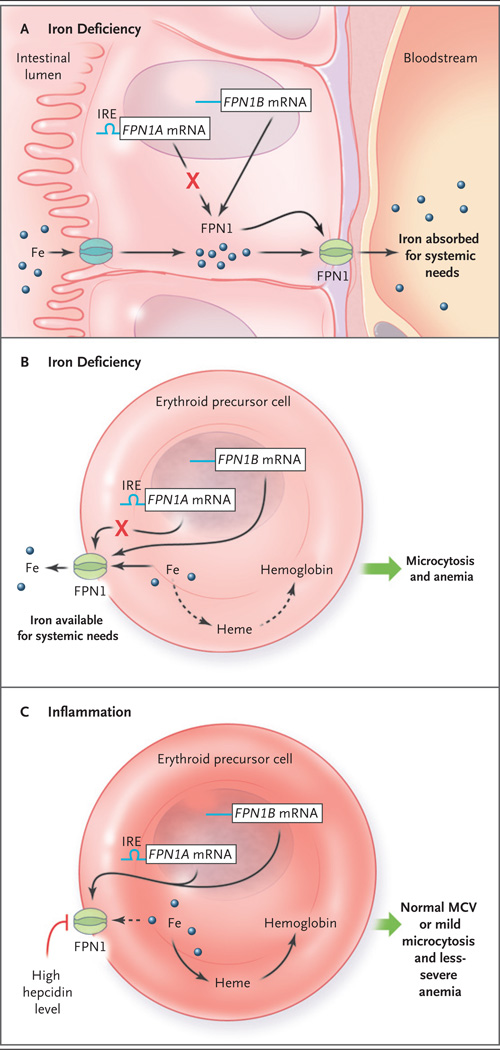

Figure 1. Models of Iron Processing in Cases of Iron Deficiency and Inflammation.

Panel A shows the duodenal enterocyte in the irondeficient state, in which translation of the ferroportin FPN1A messenger RNA (mRNA) transcript (blue line) is repressed (as mediated through its iron-responsive element [IRE]) but levels of FPN1B mRNA transcripts (blue line) — the existence of which was recently described by Zhang et al.2 — increase, and thus the level of the FPN1 protein is maintained. Because the hepcidin level is low, iron is efficiently exported, through FPN1, to the systemic circulation. Erythroid precursors function similarly to enterocytes in the context of iron deficiency (Panel B). FPN1 remains on the cell surface, and iron is exported out of the erythroid precursor for systemic needs. This results in a decreased heme level, and in turn, decreased hemoglobin synthesis, reflected clinically as microcytosis and anemia. In the context of inflammation (Panel C), interleukin-6 and other cytokines stimulate (by means of an iron-independent mechanism) hepatocytes to secrete high levels of hepcidin. Hepcidin triggers FPN1 degradation, blocking iron export from erythroid precursors (dashed arrow), resulting in a relative preservation of hemoglobin synthesis, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), and red-cell production.