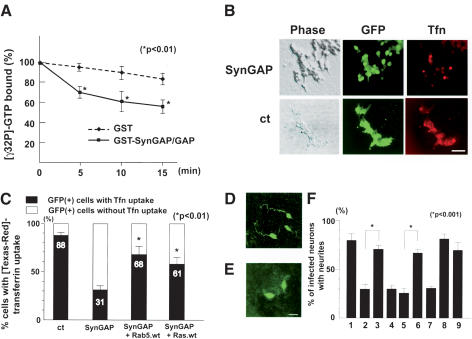

Figure 6.

SynGAP functions as a Rab5 GAP. (A) The GAP domain of SynGAP stimulates Rab5 GTPase activity in vitro. Time course of the GTPase activity of the GST–Rab5 fusion protein in the presence or absence of the GAP domain of SynGAP. Incubation of a GST–Rab5 with a control GST protein (diamonds) had minimum effect on the slow intrinsic GTPase activity of GST–Rab5. In contrast, addition of the GST–SynGAP/GAP fusion protein accelerated the GTPase activity of GST–Rab5 (squares). Asterisks show significant decrease in the amount of bound [γ-32P]-GTP at each time point (p < 0.01). (B) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with either SynGAP + GFP or GFP alone, and assayed for their ability to uptake [Texas-red]-conjugated transferrin. Transfected cells were identified by GFP epifluorescence. Although a majority of control cells showed transferrin uptake, fewer cells displayed uptake after SynGAP overexpression. Bar, 50 μm. (C) Quantitation of cells uptaking transferrin after SynGAP or SynGAP + Rab5/Ras overexpression. GFP-positive cells with or without transferrin were scored and counted from three independent experiments. The data are mean ± S.E. of percentages of transferrin-positive cells (closed column) or transferrin-negative cells (open column); 88.2% ± 3.6%, 31.5% ± 4.1%, 68.0% ± 8.0%, or 61.3% ± 4.9% of GFP-positive cells were transferrin-positive when transfected with vector + GFP, SynGAP + GFP, SynGAP + Rab5.wt + GFP, or SynGAP + Ras.wt + GFP plasmids, respectively. Asterisks show significant increase in transferrin uptake (p < 0.01) compared with SynGAP-induced down-regulation of the uptake. (D) Cerebellar granule cells infected with retroviruses expressing both SynGAP and GFP–Rab5 restored axon extension. (E) Cerebellar granule cells infected with retroviruses expressing SynGAP and GFP showed truncated morphology. Infected cells and morphology were determined by anti-GFP antibody staining. Bar, 10 μm. (F) Quantitation of granule cells harboring neurites. Granule cells were infected with retroviruses expressing GFP alone (column 1), SynGAP + GFP (column 2), SynGAP + GFP–Rab5.wt (column 3), SynGAP + GFP–Rab5.S34N (column 4), Unc51.1.KR + GFP (column 5), Unc51.1.KR + GFP–Rab5.wt (column 6), Unc51.1.KR + GFP–Rab5.S34N (column 7), GFP–Rab5.wt (column 8), or GFP–Rab5.S34N (column 9), and the percentage of cells harboring neurites (>20 μm) was scored. A hundred cells per experiment were scored for the presence or absence of neurites and were counted from at least three individual experiments. Data for columns 1 and 2 were carried over from Figure 4C: 79.5% ± 6.2% (column 1), 30.8% ± 7.0% (column 2), 72.0% ± 3.2% (column 3), 32.3% ± 3.0% (column 4), 25.8% ± 4.5% (column 5), 66.2% ± 3.2% (column 6), 33.1% ± 1.6% (column 7), 82.0% ± 6.1% (column 8), or 69.4% ± 8.3% (column 9) of cells expressing the indicated proteins extended neurites. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.001) were observed between columns 2 and 3, and 5 and 6, as indicated by asterisks.