Abstract

To begin accounting for cultural and contextual factors related to child rearing among Mexican American parents we examined whether parents' Mexican American cultural values and perceptions of neighborhood danger influenced patterns of parenting behavior in two-parent Mexican-origin families living in the U.S. To avoid forcing Mexican American parents into a predefined model of parenting styles, we used latent profile analysis to identify unique patterns of responsiveness and demandingness among mothers and fathers. Analyses were conducted using parent self-reports on parenting and replicated with youth reports on mothers' and fathers' parenting. Across reporters most mothers and fathers exhibited a pattern of responsiveness and demandingness consistent with authoritative parenting. A small portion of parents exhibited a pattern of less-involved parenting. None of the patterns were indicative of authoritarianism. There was a modicum of evidence for no nonsense parenting among fathers. Both neighborhood danger and parents' cultural values were associated with the likelihood of employing one style of parenting over another. The value of using person-centered analytical techniques to examine parenting among Mexican Americans is discussed.

Keywords: parenting, culture, neighborhoods, Mexican American

Over the last decade, alongside continued growth of the U.S. Latino population (Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011), the amount of scholarship devoted to describing Latino parenting has increased substantially (Chao & Otsuki-Clutter, 2011). To date, this research can largely be characterized as variable-centered, in which parenting variables are examined relative to antecedents or outcomes, sometimes while holding constant the influence of other parenting variables. Scholars have examined either specific parenting behaviors (e.g., acceptance; Cabrera, Shannon, West, & Brooks-Gunn, 2006; Carlson & Harwood, 2003) or parenting styles (e.g., authoritative; Domenech Rodríguez, Donovick, & Crowley, 2009; Varela et al., 2004), most commonly with an emphasis on mothers. Still, some research suggests that Latino parents may uniquely package parenting behaviors to achieve desired socialization goals in specific U.S. contexts (Carlson & Harwood, 2003; Coatsworth et al., 2002; Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003). The potential for unique packaging renders the specific-behavior approach less suitable because parents' use of a specific behavior may only be meaningful vis-à-vis their use of other parenting behaviors. Unique packaging also renders the parenting styles approach potentially less useful because Latino parents may employ unique combinations of parenting behaviors not captured by the predominant parenting styles frameworks (Baumrind, 1971; Maccoby & Martin, 1983).

García Coll and colleagues (1996) have recognized the combined contributions of traditional culture and U.S. ecology in shaping minority parents' parenting. The combined influence of parents' traditional cultural values and exposure to U.S. contexts may produce new parenting styles (ones not captured by variable-centered approaches), which have been conceptualized as minority parents' attempt to adapt to ecological challenges encountered in the U.S. (García Coll et al., 1996). One ecological challenge that is particularly important to investigate is residence in low-quality and dangerous neighborhoods with high rates of concentrated disadvantage (Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls, 1997), as Latinos experience disproportionate exposure to these neighborhoods (South, Crowder & Chavez, 2005). Only two quantitative studies have examined the ways that cultural values and exposure to dangerous neighborhoods in the U.S., together, influenced parenting (White & Roosa, 2012; White, Roosa, & Zeiders, 2012), but these authors looked at individual behaviors rather than parenting styles. Most other investigations have looked at cultural values (Calzada, Fernandez, & Cortes, 2010) or context (White, Roosa, Weaver, & Nair, 2009) independently. Finally, most Latino parenting research has employed samples of families from a variety of national origins, failing to acknowledge historical, cultural, and behavioral differences among these groups and assuming the results apply equally to each.

It is important to conduct parenting research that addresses specific limitations associated with the variable-centered approach and further illuminates the ways in which cultural values and dangerous U.S. neighborhood contexts influence parenting among Mexican American mothers and fathers because people of Mexican origin comprise the largest subgroup (63%) of Latinos (Ennis et al., 2011). Consequently, our first aim was to employ a person-centered approach to the study of Mexican American parenting styles. A person-centered approach does not define parenting styles according to a predetermined typology; rather, it allows naturally occurring groups with unique variable patterns to emerge from the data (Bergman, 2001). Our second aim was to examine the ways in which Mexican American cultural values and exposure to dangerous neighborhood contexts influence parents' parenting styles. We focused on two-parent Mexican American families because Mexican Americans are highly likely to raise their children in two-parent families (Suro et al., 2007).

Mexican American Parents' Parenting Styles

Baumrind's (1971) and Maccoby and Martin's (1983) works, wherein they jointly defined four unique parenting styles characterized along two parenting dimensions, represent the predominant parenting style typologies. Responsiveness refers to affection and attentiveness to children's developmental needs. Behaviorally, responsive parents are accepting (regular displays of warmth and support toward their children) and non-punitive (avoid harsh parenting characterized by punitive or demeaning behaviors; Simons & Conger, 2007). Demandingness refers to control, expectations for child behavior, and implementation and enforcement of clear standards and rules (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2009). Behaviorally, demanding parents engage in parental control, surveillance, and knowledge of children's actions, whereabouts, and friends via monitoring (Small & Kerns, 1993); and consistently respond to child misbehavior (Simons & Conger, 2007). The most optimal style, authoritative parenting, is characterized by high responsiveness and demandingness. Authoritarian parenting combines low responsiveness with high demandingness. Indulgent parents are high on responsiveness and low on demandingness; neglectful parents are low on both dimensions. Within the Latino parenting literature there is ambiguity surrounding the discussion of parenting styles. Some scholars emphasize higher levels of control among Latino parents (Halgunseth, Ispa, & Rudy, 2006) that may be viewed as consistent with authoritarianism. Others emphasize high levels of warmth and support (Calzada & Eyberg, 2002), a balance of responsiveness and demandingness (Varela et al., 2004), or a positive relation between parental warmth and harshness (Hill et al., 2003) that is not recognized by the predominant dimensionality.

Research based on the predominant model of parenting styles has relied heavily on measurement and analytical approaches that are pre-disposed to produce results consistent with that model. For example, scholars often pre-suppose the applicability of the four styles to Mexican Americans by directly measuring levels of authoritativeness and authoritarianism (Varela et al., 2004). Another common approach is to use cutoffs, based on sample distributions, to characterize parents according to the predominant typology. When employing cutoffs, parents who fall somewhere in the middle of the distribution on behavioral indicators of responsiveness and/or demandingness are often excluded from classification and further analyses (e.g., Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn, Mounts, Steinberg, & Dornbusch, 1991). This method has important implications. First, a sample distribution could be such that those members of the sample who are described as low on some dimension are only low relative to other members of the sample, but not actually low. Second, all of those members of the sample who are excluded from classification and analysis may employ parenting styles that are not recognized by the model, but are nevertheless important and normative. Third, if some group (e.g., Mexican Americans) was disproportionately represented among the middle of a distribution of demandingness, responsiveness, or both, then members of that group may have been disproportionately excluded from cross-cultural examinations of parenting. Empirical evidence suggests that these traditional approaches to studying parenting may be problematic when working with samples of Mexican Americans because as many as 67% of Latina mothers do not employ one of the four predominant styles (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2009).

In the current examination we aimed to circumvent these limitations. First, rather than measure parents' levels of authoritarianism and authoritativeness, we measured four parenting behaviors (acceptance, harsh parenting, consistent discipline, and monitoring) and examined patterns of these behaviors, vis-à-vis the predominant dimensions, to identify unique parenting styles. Second, we used a person-centered analysis technique, which allowed for unique patterns of the four behaviors to emerge, if they were present. Recognizing several studies suggesting the cross-cultural validity of the predominant model (Driscoll, Russell, & Crockett, 2008; Steinberg, Mounts, Lamborn, & Dornbusch, 1991), we hypothesized that some Mexican American parents would display patterns of responsiveness and demandingness consistent with authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, or neglectful styles. Recognizing considerable ambiguity in the literature on Latino parenting, along with the strength of our study design to detect alternative patterns, we further hypothesized that some Mexican American parents would display patterns of parenting behaviors that did not conform to the predominant dimensionality or styles. In the following sections we discuss a possibility for at least one alternate pattern, no nonsense parenting, in light of Mexican American parents' traditional culture-driven and U.S. neighborhood-driven socialization goals.

Cultural and Contextual Influences on Mexican American Parents' Parenting

Parenting is a mechanism through which culture is expressed in the family context (Harwood, Leyendecker, Carlson, Asencio, & Miller, 2002). Parents employ parenting behaviors to teach or reinforce messages consistent with their cultural beliefs (Calzada et al., 2010) and promote social competence as defined by those beliefs (Livas-Dlott et al., 2010). Two traditional cultural values have received the bulk of attention from scholars focused on cultural influences on parenting: familism and respeto (Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2012). Familism emphasizes reciprocity, loyalty, and solidarity among family members (Calzada, Tamis-LeMonda, & Yoshikawa, 2012). Respeto emphasizes obedience to authority, deference, decorum, and appropriate public behavior (Calzada et al., 2010). Strong emphases on these values have been associated with high levels of monitoring (including knowledge), high expectations for obedience, and parents' belief in the need to use harsh parenting, because these behaviors are seen as ways to teach children about familial solidarity, obedience, and deference (Calzada et al., 2010; Romero & Ruiz, 2007). The bulk of empirical work examining the relation between parents' cultural values and parenting has relied on proxies for culture, such as ethnicity/race, nativity, generational status, or language spoken. For example, the cultural values of familism and/or respeto have been used to explain findings from cross ethnic comparisons of harsh and authoritarian parenting (Knight, Virden, & Roosa, 2004), cross-language comparisons of acceptance and harsh parenting (Hill et al., 2003), and pan-Latino examinations of parenting (Calzada & Eyberg, 2002). The general pattern observed among parents of early adolescent and adolescent-aged children is one in which, apparently due to emphases on familism and respeto, Latino and/or Mexican American parents were thought to be more authoritarian, or to employ higher levels of harshness perhaps with accompanying acceptance and support (a combination inconsistent with predominant views of responsiveness).

Parenting is also a mechanism through which neighborhood danger influences the family context (White et al., 2012). In a literature largely compartmentalized from the culture-based literature, one of two explanations is usually employed to describe the ways in which living in low quality, dangerous neighborhoods influences parenting. The adaptational perspective suggests that parents living in dangerous neighborhoods may intentionally respond to those challenges with increases in harshness and control in combination with high levels of acceptance, an approach that is inconsistent with predominant conceptualizations of responsiveness. This combination, sometimes called no nonsense parenting, is viewed as an attempt to protect children from the harsh realities they are likely to face (Furstenberg et al., 1993; Letiecq & Koblinsky, 2004). In contrast, the neighborhood family stress process perspective (White et al., 2012), which draws heavily from the Family Stress Model (Conger et al., 2010), suggests that the stress experienced in response to living in dangerous neighborhoods is disruptive to parenting. This disruption manifests as lower levels of responsiveness (i.e., lower acceptance and higher harsh parenting) and demandingness. It is unclear whether Mexican Americans respond to perceived neighborhood danger in a manner consistent with adaptational (Cruz-Santiago & Ramirez-Garcia, 2011), or stress process perspectives (White et al., 2012) and this may be due, in part, to the methods previously employed. For example, when examining harsh parenting alone, or while controlling for other parenting behaviors, scholars may not be able to determine if a positive relation between neighborhood danger and harsh parenting is indicative of stress or adaptation (White & Roosa, 2012). An examination of patterns of parenting behaviors, in which harshness and acceptance are considered simultaneously, will facilitate a better understanding of Mexican American parents' responses to living in dangerous U. S. neighborhoods.

We aimed to circumvent the limitations of both the cultural and contextual literatures. Using the results generated from the person-centered analysis of parenting, we explored the degree to which parents' traditional cultural values and perceptions of neighborhood danger related to increased or decreased odds of employing a given parenting style over another. We moved beyond proxies and assessed parents' levels of familism and respeto as indicators of Mexican American cultural values. Based on the pattern of findings from the proxy-based literature, in which Latino parents are described as either more authoritarian or as uniquely combining harsh parenting with acceptance, we hypothesized that parents who endorsed higher cultural values would be more likely to display parenting styles characterized by high demandingness and low responsiveness, or high demandingness and a pattern of both high acceptance and higher harshness. Due to a strong emphasis on family support and obligations, we also expected these parents would be less likely to be low on both dimensions (i.e., neglectful).We also examined the influence perceived neighborhood danger had on parenting styles. We hypothesized that the influence of neighborhood danger would either be consistent with a neighborhood stress-process perspective (i.e., simultaneous disruption of both parenting dimensions) or an adaptational perspective (i.e., high demandingness accompanied by high acceptance and higher harsh parenting).

Method

Data for this study are from a larger study of the roles of culture and context in the lives Mexican American families (N = 749; Roosa et al., 2008). Participants were families of students in 5th grade classrooms within schools in a large metropolitan area of the southwestern U.S. Eligible families met these criteria: (a) they had a fifth grader attending a sampled school; (b) mother and youth agreed to participate; (c) the mother was the child's biological mother, lived with the child, and self-identified as Mexican or Mexican American; (d) the child's biological father was of Mexican origin; (e) the child was not severely learning disabled; and (f) no step-father or mother's boyfriend was living with the child. The current study focused on the sub-sample of two-parent families in which both the mother and father participated (82% of eligible fathers, N = 466). Among these, four were omitted for missing data, so the final analyses focused on 462 mother-father-youth triads. Those families in which fathers participated were similar to those two-parent families in which fathers did not participate on income, child nativity, father nativity, child gender, and child reports on paternal parenting. Youth (48.1% female) were, on average, 10.4 (SD = .55) years old. A majority of youths were born in the U.S. (66.9%) and completed the interview in English (81.8%). Average ages for the samples of mothers and fathers were 35.7 (SD = 5.6) and 38.1 (SD = 6.3), respectively. A majority of mothers (78.6%) and fathers (79.9%) were born in Mexico [average number of years in U.S. = 12.3 (SD = 7.9) for mothers and 15.0 (SD = 8.5) for fathers] and completed the interview in Spanish (72.7% and 76.6%, respectively). Average annual family income was $35,001 – $40,000. For fathers, 91% were employed full time; for mothers this figure was 39%. Years of education ranged from 1 to 20 (M = 10.1) for fathers and 1 to 19 (M = 10.3) for mothers. Families lived in diverse neighborhoods with poverty rates ranging from 0% to 81.3%, according to 2000 Census data.

Study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the first author's university. The complete procedures are described elsewhere (Roosa et al., 2008). The research team originally identified communities served by 47 public, religious, and charter schools chosen to represent the metropolitan area's economic, cultural, and social diversity. Recruitment materials were sent home with all 5th grade youth in these schools. Computer Assisted Personal Interviews lasting about 2 ½ hours were completed with 749 families, 73% of those eligible. Question and response options were read aloud in participants' preferred languages. Each participant was paid $45 for participating in the interview. The sample was similar to the census description of this population on parent education and family income (Roosa et al.).

Measures

All study materials and measure were translated from English to Spanish using translation/back translation procedures. We have presented detailed evidence of construct validity, reliability, and cross-language measurement equivalence of both parent and youth versions of each measure elsewhere (Kim, Nair, Knight, Roosa, & Updegraff, 2009; Knight et al., 2010; Nair, White, Knight, & Roosa, 2009). In the current study alphas ranged from .70 to .88. For parenting variables mothers and fathers reported on their own behaviors; youth reported on mothers' and fathers' behaviors separately. Unless otherwise indicated, response options ranged from 1 (almost never or never) to 5 (almost always or always). Parents responded to questions about annual family income (1 = $0,000 − $5,000 to 20 = $95,001+) and nativity.

Responsiveness

We operationalized responsiveness with two parenting behaviors, acceptance and harsh parenting, using a translated version of the Children's Report of Parent Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Nair et al., 2009). The 8-item acceptance subscale assessed warmth in the parent-child relationship (e.g., “Your mother understood your problems and worries”). The 8-item harsh parenting subscale assessed punitive or demeaning control attempts with negative affect (e.g., “your mother spanked or slapped you when you did something wrong”).

Demandingness

We operationalized demandingness with measures of consistent discipline and monitoring. The measure of consistent discipline was an 8-item subscale that assessed rule-setting and how consistently the parent responded to the child's misbehaviors from the CRPBI (“When you broke a rule, your mother made sure you received the punishment she said you would get”). The measure of monitoring was an 8 item adaptation of Small and Kerr's (1993) parental monitoring scale (e.g., “Your [parent] knew who your friends were”).

Mexican American cultural values

Parents responded to the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight et al., 2010). The current study used four subscales to assess each parents' adherence to traditional cultural values: Familism – Support (6 items, e.g., “It is always important to be united as a family”), – Obligations (5 items, e.g., “If a relative is having a hard time financially, one should help them out if possible”), – Referent (5 items, e.g., “A person should always think about their family when making important decisions”), and Respect (8 items, e.g., “Children should never question their parents' decisions”). Parents indicated their endorsement of each item by responding on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very much). Because prior work demonstrated that all four subscales load on a single latent factor (Knight et al.), we calculated a mean score to represent cultural values.

Neighborhood danger

Parents reported on their own perceptions of the degree of danger in their neighborhoods by indicating their level of agreement (1 = not true at all to 5 = very true) on a 3-item subscale of the Neighborhood Quality Evaluation Scale (e.g., “It is safe in your neighborhood,” reverse coded). Higher scores reflect a higher sense of danger.

Results

Latent Profile Analyses

We utilized latent profile analysis (LPA), a technique used to examine patterns of continuous variables under the assumption that there are unobserved subgroups with similar association between variables in a given population (Geiser, Lehmann, & Eid, 2006). The goal in LPA is to identify groups of families whose patterns on variables (i.e., acceptance, harsh parenting, consistent discipline, and monitoring) are highly similar. LPA models proceed in a series of steps starting with a one-profile model solution (independent means model). The number of profiles is then increased in each step and a series of fit indices are examined to decide which profile solution best fits the data. The best fitting model was determined by information criteria (IC) and likelihood ratio (LR) tests, and interpretability. For ICs, researchers have recommended the Bayesian information criteria (BIC) and the sample size adjusted BIC (ABIC; Tein, Coxe, & Cham, in press). For the BIC and ABIC a lower value represents a better fitting model. The Voung-Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001) test can be used to determine whether a model with a given number (k) of profiles significantly fits the data better than a simpler model with one profile less (k – 1; Tofighi & Enders, 2006). A significant LMR test value indicates that the model in which k profiles are specified is a better fitting than the k-1 profile model. For all analyses a 1 through 5 profile solution was estimated.

Mothers' parenting styles

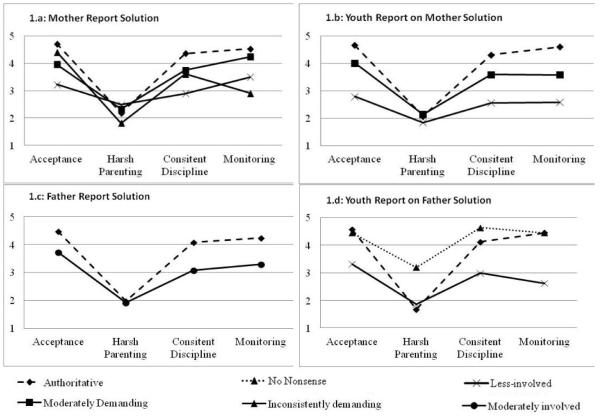

Based on optimal fit indices and interpretability (Table 2), the 4-profile solution was selected as the final model for the mother-report data (Figure 1.a). The majority of mothers (64.7%) were high on responsiveness and demandingness and we labeled this profile as authoritative. Nearly 20% of mothers were high on responsiveness with lower levels of demandingness and we labeled this profile as moderately demanding. Ten percent of mothers were high on responsiveness, moderate on consistent discipline, and lower on monitoring, a pattern we labeled inconsistently demanding. Finally, 4.9 % of mothers were lower on almost all indicators, a pattern we labeled less involved. The 3-profile solution was selected as the final model for the youth-report data (Table 2, Figure 1.b). According to this solution, the majority of mothers (70.1%) were high on responsiveness and demandingness and we labeled this profile authoritative. Nearly 25% of mothers were high on responsiveness with slightly lower levels of demandingness and we labeled this profile moderately demanding. Finally, 5.1% of mothers were lower on almost all indicators, and we labeled this profile less involved.

Table 2.

Model Fit indices and final entropies for latent profile analyses (N = 462)

| BIC | ABIC | p LMR | Entropy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother Report | ||||

| 1 profile | 3600.99 | 3575.60 | -- | |

| 2 profiles | 3387.10 | 3345.84 | .001*** | |

| 3 profiles | 3335.53 | 3278.40 | .09† | |

| 4 profiles | 3307.40 | 3234.40 | .03 * | .83 |

| 5 profiles | 3291.82 | 3202.96 | .47 | |

| Youth Report on Mother | ||||

| 1 profile | 4024.12 | 3998.73 | -- | |

| 2 profiles | 3667.63 | 3626.37 | .0003*** | |

| 3 profiles | 3562.42 | 3505.29 | .03 * | .86 |

| 4 profiles | 3501.19 | 3428.20 | .05† | |

| 5 profiles | 3477.67 | 3388.80 | .13 | |

| Father Report | ||||

| 1 profile | 3762.470 | 3737.080 | -- | |

| 2 profiles | 3524.078 | 3482.819 | .0001 *** | .71 |

| 3 profiles | 3490.547 | 3433.420 | .09† | |

| 4 profiles | 3475.149 | 3402.153 | .10 | |

| 5 profiles | 3469.808 | 3380.943 | .19 | |

| Youth Report on Father | ||||

| 1 profile | 4470.28 | 4444.89 | -- | |

| 2 profiles | 4048.82 | 4007.57 | .0001*** | |

| 3 profiles | 3994.97 | 3937.85 | .001 * | .86 |

| 4 profiles | 3954.39 | 3881.39 | .30 | |

| 5 profiles | 3924.32 | 3835.45 | .64 | |

Note. BIC = Bayesian information criterion; ABIC adjusted BIC; LMR = Lo-Mendell-Rubin.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Bolded indicates the solution that was selected as the best fitting model. Entropies were not used to assess model fit.

Figure 1.

Profile means for four latent profile analysis solutions (N = 462)

Fathers' parenting styles

For the father-report solution the 2-profile solution provided optimal fit and interpretability (Table 2). The majority of fathers (63.6%) were high on responsiveness and demandingness and we labeled this profile authoritative (Figure 1.c). The remaining fathers (36.6%) had lower levels of responsiveness and demandingness, a pattern we labeled moderately involved. We interpreted the 3-profile solution from the youth-report data (Table 2 and Figure 1.d). The majority (70.7%) of fathers were authoritative. Nearly 17% of fathers were lower on all indicators and we labeled this profile less involved. Finally, 12.3% of fathers belonged to a profile we labeled no nonsense. These fathers were high on demandingness and acceptance, and relatively higher on harsh parenting. The father-report solution was the only solution that did not contain a less involved profile; their moderately involved profile was highly comparable to all less involved profiles in that it represented lower levels of both dimensions.

Mexican American Cultural Values, Neighborhood Danger, and Parenting

We estimated multinomial logistic regressions in MPLUS with the COMPLEX command and maximum likelihood restricted estimation, which adjusted the standard errors of path coefficients for neighborhood clustering and offered parameter estimation that was robust to nonnormality (Muthén & Muthén, 2010), to examine the relation between parenting profiles and parents' cultural values and exposure to neighborhood danger. Profile memberships obtained from the LPA solutions were assigned to each family. Treating profiles as observed, rather than latent, in analyses such as these is acceptable when the entropy is above .80 (Clark & Muthén, 2010), which was the case for three of the four solutions obtained (Table 2). To address the lower entropy for the father-report solution we utilized a more stringent p-value (p < .01, 99% confidence interval; Clark & Muthén, 2010). Observed profile membership was regressed on parental perceptions of neighborhood danger and parents' cultural values. Youth gender, parent nativity, and family income were entered as control variables in all models. In all analyses the reference group was authoritative. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Odds ratios from multinomial logistic regressions of parenting styles on parents' cultural values and perceptions of U.S. neighborhood danger (N = 462)

| Mothers' Parenting Styles | Fathers' Parenting | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Mother-report OR (95% CI) | Youth-report OR (95% CI) | Father-report OR (99% CI) | Youth-report OR (95% CI) | |

| Covariates | ||||

| Boy youth | ||||

| Authoritative | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mod demand | 1.06 (.66, 1.68) | 1.64 (1.06, 2.54) | -- | -- |

| Incon demand | 0.69 (.36, 1.33) | -- | -- | -- |

| Mod involved | -- | -- | .69 (.40, 1.22) | -- |

| No nonsense | -- | -- | -- | 1.47 (.84, 2.57) |

| Less involved | 1.61 (.70, 3.71) | 1.22 (.55, 2.70) | -- | 1.11 (.67, 1.86) |

| Parent Mexican Nativity | ||||

| Authoritative | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mod demand | 0.93 (.51, 1.70) | 1.89 (1.0, 3.59) | -- | -- |

| Incon demand | 3.37 (.69, 16.30) | -- | -- | -- |

| Mod involved | -- | -- | 1.38 (.62, 3.06) | -- |

| No nonsense | -- | -- | -- | 1.08 (.55, 2.13) |

| Less involved | 1.45 (.23, 9.21) | 3.78 (.73, 19.52) | -- | 1.91 (.74, 4.91) |

| Family Income | ||||

| Authoritative | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mod demand | 1.04 (.98, 1.10) | 1.00 (.94, 1.06) | -- | -- |

| Incon demand | 0.87 (.80, .94) | -- | -- | -- |

| Mod involved | -- | -- | .94 (.88, 1.01) | -- |

| No nonsense | -- | -- | -- | 1.01 (.94, 1.08) |

| Less involved | 1.02 (.88, 1.13) | 1.03 (.92, 1.14) | -- | .98 (.91, 1.05) |

| Culture & Neighborhood Context | ||||

| Cultural Values | ||||

| Authoritative | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mod demand | 0.38 (.20, .71) | .88 (.50, 1.55) | -- | -- |

| Incon demand | 0.57 (.23, 1.43) | -- | -- | -- |

| Mod involved | -- | -- | .21 (.10, .47) | -- |

| No nonsense | -- | -- | -- | .64 (.33, 1.26) |

| Less involved | 0.24 (.09, .62) | .46 (.16, 1.30) | -- | 1.33 (.65, 2.73) |

| Neighborhood Danger | ||||

| Authoritative | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mod demand | 1.14 (.90, 1.38) | 1.21 (.94, 1.55) | -- | -- |

| Incon demand | 1.36 (.98, 1.90) | -- | -- | -- |

| Mod involved | -- | -- | 1.83 (1.34, 2.51) | -- |

| No nonsense | -- | -- | -- | 1.24 (.87, 1.79) |

| Less involved | 1.66 (1.06, 2.59) | 1.59 (1.01, 2.51) | -- | 1.40 (1.08, 1.81) |

Note: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Mod demand = Moderately demanding; Incon demand = Inconsistently demanding; Mod involved = moderately involved. For all analyses authoritative is the reference category. ORs in bold are significant: p < .05, or (for father-report solution) p < .01.

Mothers' parenting styles

When the mother-report solution was used mothers' cultural values were associated with significantly lower odds of being less involved vs. authoritative and of being moderately demanding vs. authoritative. For example, the .24 odds ratio can be interpreted as follows: for every one-unit increase in cultural values the odds of belonging to the less involved group decreases by 76%. Neighborhood danger was associated with significantly higher odds of being less involved vs. authoritative. For every one-unit increase in perceived neighborhood danger, there was a 66% increase in the odds of being less involved relative to authoritative. When the youth-report solution was used mothers' cultural values were not related to profile membership. Neighborhood danger was associated with significantly greater odds of being less involved vs. authoritative.

Fathers' parenting styles

When the father-report solution was used fathers' cultural values were associated with significantly lower odds of being moderately involved vs. authoritative. Neighborhood danger was associated with significantly higher odds of being moderately involved vs. authoritative. When the youth-report solution was used fathers' cultural values did not relate to profile membership. Fathers' perceptions of neighborhood danger were associated with increased odds of being less involved vs. authoritative. Due to the strong interest in no nonsense parenting, we ran a model in which no nonsense parenting was the comparison group, allowing for a statistical contrast of no nonsense parenting to less involved parenting. None of the variables in the model were significant in this contrast.

Alternate model testing

Our finding that parents' perception of neighborhood danger consistently relate to a higher odds of being less involved (or moderately involved in the father-report solution) could be explained by any number of more global forms of parental stressors that co-occur with residence in low quality, disadvantaged, and dangerous neighborhoods (e.g., a lack of financial, material, other resources). Further, neighborhood scholars are often concerned about selection effects (Sampson et al., 1997), which may manifest in the current study as less (moderately) involved parents selecting into bad neighborhoods. Consequently, in addition to controlling for family income differences in all models, we conducted post-hoc tests of the hypothesized models wherein we substituted a measure of concentrated disadvantage for our measure of parents' perceived danger. Concentrated disadvantage was represented by a composite of Census 2000 tract-level data on neighborhood rates of poverty, single parent households, and unemployment (Sampson et al.). Replication of the neighborhood danger findings with the concentrated disadvantage measure would support the following alternative explanations for study findings: (a) the more global stressors associated with residence in disadvantaged neighborhoods, not the specific stress associated with living a neighborhood that parents perceive to be dangerous, are important for understanding parenting; and (b) less involved parents may have selected into bad neighborhoods. Across all four alternate models, we did not observe any replication.

Discussion

This study drew on cultural-ecological perspectives to explore parenting among two-parent Mexican-origin families with early adolescent-aged children. Our findings contribute to existing Latino parenting scholarship in several ways. First, the identification of distinct patterns of parenting behaviors extends research on Latino parenting in new directions. Examining patterns of acceptance, harshness, consistent discipline, and monitoring among Mexican American mothers and fathers moves the field beyond (a) a focus on specific parenting behaviors, and (b) the predominant model of parenting styles. Our approach allowed for styles to emerge from the data that were both consistent with and potentially unique from the predominant model. Second, our findings revealed that both culture and neighborhood danger play important roles in shaping Mexican American mothers' and fathers' parenting.

Mexican American Parents' Parenting

We identified six patterns of parenting among Mexican American mothers and fathers. One pattern was consistent with authoritative parenting, providing clear and partial replication of the predominant model. A second pattern, which we described as less involved parenting, mirrored qualitative patterns of neglectful parenting, but did not appear as quantitatively extreme as prior interpretations of neglectful parenting imply. A third pattern was characterized as no nonsense parenting, providing preliminary evidence that the predominant model may need to be extended to adequately capture parenting among Mexican American families. Of the remaining three patterns identified in the current study, two were highly responsive but varied in patterns of demandingness (moderately demanding and inconsistently demanding), and one was moderate on responsiveness and demandingness (moderately involved).

Replication and extension of the predominant model of parenting

Consistent with several studies suggesting the cross-cultural validity of the predominant typology (Driscoll et al., 2008; Steinberg et al., 1991), we found that most mothers and fathers employed combinations of responsiveness and demandingness consistent with traditional conceptualizations of authoritative parenting (Maccoby & Martin, 1983). Importantly, these results replicated across mothers' and fathers' own reports on their parenting behaviors and across youth reports on parents. Further, the results are not only consistent with prior cross-cultural examinations (Driscoll et al., 2008), but also with research among Latino parents. For example, employing a variable-centered approach, Calzada and Eyeberg (2002) found that a sample of immigrant and first-generation Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers engaged in high levels of responsive parenting, coupled with high levels of consistency and discipline and low levels of physically or psychologically harsh parenting. The current work replicates those findings with a multigenerational sample of Mexican American mothers and fathers using notably distinct methods. As a consequence, we feel that the evidence in support of parenting characterized as highly responsive and demanding among diverse parents, including Mexican Americans, has been strengthened.

As many as 5% of Mexican American mothers and 17% of Mexican American fathers fell into a profile that we labeled less involved. Less involved parents employed levels of harsh parenting that were comparable to most other profiles, along with lower levels of acceptance and demandingness. Mean scores on acceptance, consistent discipline, and monitoring for these parents, however, tended to be near the midpoint of the scale. Such means seemed inconsistent with parental disengagement, a concept emphasized in theoretical conceptualizations of neglectful parenting (Lamborn et al., 1991), which is why we labeled this profile as less involved. Our findings and conclusions are somewhat consistent with prior variable-driven parenting research among Latino parents, which found that only 1% of the sample could be characterized as neglectful (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2009). The mean on cultural values in our sample was relatively high; perhaps even a moderate emphasis on familism and respeto may be effective at preventing complete neglect. Importantly, our less involved parents may or may not be unique from parents described as neglectful in previous work. Given the emphasis on cutoffs and sample distributions in prior work (e.g., Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn et al., 1991) it is possible that the parents we have classified as less involved would be classified as neglectful by traditional methods. Our findings emphasize limitations associated with the variable-centered and sample cut-off approaches: using cut-offs, we may have labeled these parents neglectful because they were low, relative to the sample, on behavioral indicators of responsiveness and demandingness. A person-centered approach and a closer look at the actual values on those indicators reveals that these parents probably were not disengaged.

We found some support for our hypothesis that Mexican American parents might employ styles not captured by the predominant typology: 12% of fathers in the current study, according to the youth-report model, were characterized as no nonsense. These fathers packaged high demandingness with high acceptance and moderate levels of harsh parenting. The mean level of paternal acceptance among fathers characterized as no nonsense was as high as the mean level of acceptance observed among fathers characterized as authoritative (Figure 1.d). Consequently, we found this pattern to be inconsistent with prior conceptualizations of authoritarian parenting, which, by definition, should include lower levels of responsiveness (Lamborn et al., 1991). Instead, this strategy appears qualitatively unique from any of the parenting styles defined by the predominant model. Further, this pattern of behaviors is inconsistent with predominant conceptualizations of responsive parenting. Research on parenting among minority families has repeatedly pointed to parenting characterized by both higher levels of warmth and higher levels of harshness (Julian, McKenry, & McKelvey, 1994; Steele, Nesbitt-Daly, Daniel, & Forehand, 2005; Varela et al., 2004) and numerous studies suggest that ethnic minority families generally and Latino families specifically may uniquely package warmth and harshness to achieve desired socialization goals (e.g., Hill et al., 2003), perhaps in light of disproportionate exposure to low-quality neighborhoods (Furstenberg et al., 1993). Still, this style was only identified in one of four empirical solutions, and even then only characterized 12% of fathers. Consequently, replication and extension of this finding in other samples is necessary to determine (a) if the underlying dimensionality of parenting is inadequate for research with Mexican Americans, and (b) if this is an important and overlooked style among Mexican American (or other) families.

Other parenting styles identified by the person-centered approach

Three additional profiles were detected, but we interpret them cautiously because it is not clear whether they are unique to Mexican Americans, or represent parenting styles that have simply been overlooked by scholars doing research on the predominant model using variable-centered approaches and sample cut-off techniques. A fifth or more of the Mexican American mothers (according to both mother and youth reports) were grouped in a profile that mirrored authoritativeness with slightly lower demandingness (moderately demanding). For fathers, a similar profile emerged (moderately involved), again mirroring authoritativeness, but with slightly lower demandingness and responsiveness. A third profile was labeled inconsistently demanding, due to mothers' lower scores on monitoring, which deviated from predominant conceptualizations of demandingness. All three of these styles share a common attribute: group means on one or more indicators of responsiveness and/or demandingness fell somewhere in the middle of the sample distribution. The identification of a relatively sizeable group (36%) of these three different kinds of middle-of-the-road Mexican American parents underscores concerns raised earlier: Mexican Americans could have been disproportionately excluded from cross-cultural examinations of parenting styles (Lamborn et al., 1991). Alternatively, these parents may have been captured by prior work, but labeled differently. For example, work based on sample cut-offs may have interpreted that, overall, the groups we labeled as moderately demanding and inconsistently demanding were low on demandingness and, consequently, labeled these parents as indulgent.

Using the commonly applied sample-specific cut-off approach, we might have also been able to identify a group of authoritarian Mexican American parents, ones high on demandingness and low on responsiveness. Using a person-centered approach, we did not observe a pattern of meaningfully disparate levels of demandingness relative to responsiveness that we felt was consistent with authoritarian parenting. The apparent lack of an authoritarian strategy may reflect a lack of authoritarian parents among Mexican Americans, or it may reflect methodological differences between the LPA approach and prior approaches. Still, prior work focused on Latino parenting that was not based on sample cutoffs also found no evidence of authoritarian parenting among Latino parents (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2009). Despite the fact that the current study used self-report vs. observational measures and person-centered vs. variable-centered analytic techniques, our results appear to replicate those findings. Much of the prior work that references authoritarianism among Mexican Americans examines a specific parenting behavior (e.g., harshness), not broader dimensions of parenting, or patterns of parenting behaviors. For example, Knight et al. (1994) identified higher harsh parenting among Hispanic families compared to European Americans and discussed this single parenting behavior in the context of a broader parenting style (authoritarianism). Similarly, Calzada and Eyberg (2002) and Hill et al. (2003) examined individual parenting behaviors when they discussed cultural correlates of authoritarianism. Future work interested in harsh parenting among Mexican Americans may benefit from examining it vis a vis other parenting behaviors that take place in the family system.

The Influence of Cultural Values and U.S. Neighborhood Danger on Parenting

Based on a cultural-ecological perspective (García Coll et al., 1996), we hypothesized parents' cultural values and their exposure to danger in U.S. neighborhood contexts would relate to their parenting styles. Our study hypotheses received partial support. Mothers who scored higher on cultural values were more likely to be authoritative than moderately demanding or less-involved. Fathers who scored higher on cultural values were more likely to be authoritative than moderately involved. Overall, these parents appear more likely to employ high levels of responsiveness and demandingness than to display somewhat diminished levels of either dimension. When values are measured directly, rather than by proxy, a strong emphasis on familism and respeto among Mexican American mothers and fathers is associated with high levels of responsive and demanding parenting. Mexican American cultural values appear to promote the authoritative strategy, over those strategies that are less-than authoritative, perhaps because a balance of responsiveness and demandingness is viewed as the best way to promote social competence in their children (Livas-Dlott et al., 2010) and because these strategies are consistent with the values of familism and respeto.

For the main effect of parents' perceptions of neighborhood danger on parenting, our findings were mostly consistent with the stress process perspective. We found, across parent- and youth- profile solutions, that mothers' and fathers' reports on neighborhood danger were related to a lower likelihood of being authoritative and a higher likelihood of being less involved or moderately involved. Parents' reports on neighborhood danger distinguished between the authoritative profile and all profiles in which both demandingness and acceptance were substantially diminished. We, however, observed no corresponding amplification of parental harshness that would be expected under traditional conceptualizations of parental responsiveness and under traditional stress-process models (Conger et al., 2010). These findings are consistent with recent prospective, variable-centered approaches to examining neighborhood and family intersections among Mexican Americans, which have shown diminished acceptance and consistent discipline in response to neighborhood stress, but no corresponding increase in parental harshness (Gonzales et al. 2011; White et al., 2009).

Contrary to an adaptational neighborhood hypothesis, though youth did describe patterns of fathers' parenting behavior consistent with a no nonsense approach, fathers' perceptions of neighborhood danger did not relate to odds of employing this style. Based on prior Latino parenting and neighborhood research (Furstenberg et al., 1993; Hill et al., 2003), we expected this particular strategy to be most contextually and culturally charged. Yet, neither fathers' cultural values nor their reports on neighborhood danger distinguished between no nonsense fathers and other fathers. Latino parenting scholars have long discussed the possibility of a culture- and context-driven socialization strategy that combines higher levels of warmth with higher levels of harshness (see Chao & Otsuki-Clutter, 2011; Halgunseth et al., 2006 for reviews). It is possible that this parenting strategy reflects aspects of cultural values (e.g., traditional gender roles; see Knight et al., 2011) or dimensions of context not measured in the current study. For example, the increased harshness may be a mechanism Mexican American fathers employ to support ethnic socialization. Perhaps no nonsense fathers are not preparing their children for dangerous neighborhoods; rather they are trying to prepare their children for the realities of facing discrimination and devaluation because of their ethnic group membership (Chao & Otsuki-Clutter, 2011; Hughes et al., 2006), in which case other aspects of context might be more meaningful in helping to understand the use of no nonsense parenting. Examples may include neighborhood ethnic homogeneity (White, Deardorff, & Gonzales, 2012), segregation, and cultural supportiveness (Gonzales et al., 2011). Alternatively, considering that this style was not replicated with fathers' reports on parenting behaviors, there may be important child characteristics (e.g., children's cultural orientations, self-regulation) that might explain why this group of children views their fathers as both highly accepting and harsher.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Conclusions

The current study had notable strengths that should be viewed in light of its limitations. We examined parenting separately for Mexican American mothers and fathers of early adolescents from two-parent families, offering the most direct comparison to prior research on Latino parenting (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2009; Varela et al., 2004). The focus on intact families is an important one for this population, but we strongly encourage work on other family forms. We replicated all analyses with youth report on mothers' and fathers' behaviors, eliminating the influence of shared method variance in the case of cross-reporter findings for parents' perceptions of neighborhood danger. Nevertheless, our findings for parents' cultural values did not replicate when youth reports on parenting were used. Additional forms of replication (e.g., observational methods) may be useful. Further, by testing the alternate concentrated disadvantage models, we reduced the likelihood that more global forms of parental stress associated with residence in disadvantage neighborhoods and/or selection effects represent tenable explanations for our findings. Next, our investigation was cross-sectional, thus we cannot conclude that cultural values or neighborhood danger caused the observed differences in parenting styles. We addressed the two dimensions of parenting most commonly assessed in the literature on parenting styles that are represented in both Baumrind's (1971) and Maccoby and Martin's (1983) works, but a limitation of the current study is that we did not assess a third dimension: Baumrind's autonomy granting. This dimension may also be important in Latino families (Calzada & Eyberg, 2002; Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2009; Livas-Dlott et al., 2010) and should be included in future examinations. Finally, we sought to move beyond current conceptualizations of parenting by using a person-centered approach to examine patterns of four parenting behaviors. Though our approach did allow for unique packaging of these behaviors, we were unable to consider that Mexican American mothers and fathers may engage in unique behaviors, ones that have yet to be identified or understood by current theories of parenting and may be important for defining parenting styles in this group (e.g., ethnic socialization).

Despite its limitations, the current study represents an important step in understanding Mexican American parenting. The simultaneous replication and extension of the predominant model builds on prior evidence (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2009) and suggests the predominant typology may need to be extended to accurately describe parenting styles among Mexican Americans. Further, the person-centered approach may prove useful in understanding parenting in other cultural groups. We also showed that both culture and context influence parenting. Consequently, clinicians should carefully evaluate the cultural relevance of parenting intervention strategies, taking care not to inadvertently undermine maintenance of traditional values. Further, it is important to identify ways to support Mexican American parents living in dangerous neighborhoods. In their decade review, Chao and Otsuki-Clutter (2011) note that some studies explain ethnic group differences in the types of behaviors parents display by also examining the unsafe and disordered neighborhoods to which ethnic minorities are disproportionally exposed, while others point to differing cultural scripts for parenting. Though others have done important work to separate parenting beliefs rooted in normative Latino cultural tradition from those that arise in response to poverty or migration (e.g., Harwood et al., 2002), ours is the first study we know of to simultaneously examine both unsafe neighborhoods and cultural values as sources of variability in Mexican American parents' parenting styles.

Table 1.

Correlation matrix, means, and standard deviations for study variables (N = 462)

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Acc (P) | -- | .03 | −.06 | .05 | .55** | −.05 | .47** | .05 | .33** | −.22** | 4.20 | .54 |

| 2. Acc (Y) | .16** | -- | −.92 | −.13** | .06 | .45** | .09* | .59** | −.03 | −.09* | 4.34 | .72 |

| 3. Harsh (P) | −.15** | −.05 | -- | .16** | .26** | .08 | −.04 | .00 | .02 | .07 | 1.95 | .59 |

| 4. Harsh (Y) | −.07 | −.09 | .18** | -- | .02 | .30** | −.08 | −.04 | −.03 | .04 | 1.91 | .73 |

| 5. Cons (P) | .52** | .13** | .12** | .01 | -- | .07 | .39** | .09* | .26** | −.24** | 3.71 | .77 |

| 6. Cons (Y) | .12* | .51** | .06 | .28** | .14** | -- | .01 | .49** | −.05 | −.04 | 4.00 | .88 |

| 7. Mont (P) | .28** | .08 | .11* | .05 | .35** | .14** | -- | .18** | .13** | −.24** | 3.88 | .79 |

| 8. Mont (Y) | .09* | .55** | −.08 | −.01 | .11* | .53** | .20** | -- | −.03 | −.12* | 4.13 | .89 |

| 9. Cult Vals | .25** | .05 | .16** | .01 | .15** | .03 | .01 | .02 | -- | −.12* | 4.97 | .37 |

| 10. Neigh D | −.10* | −.10* | −.06 | .01 | −.12* | −.07 | −.24** | −.13** | −.12** | -- | 2.41 | .94 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mean | 4.45 | 4.40 | 2.19 | 2.08 | 4.08 | 4.03 | 4.25 | 4.24 | 4.37 | 2.50 | -- | -- |

| SD | .50 | .61 | .64 | .75 | .69 | .73 | .72 | .75 | .37 | .99 | -- | -- |

Note: Acc = acceptance; Harsh = harsh parenting; Cons = consistent discipline; Mont = monitoring; Cult Vals = Mexican American cultural values; Neigh D = neighborhood danger; (P) = parent report; (Y) = youth report. Correlations reported below the diagonal along with means and standard deviations reported in rows are for mothers. Correlations reported above the diagonal along with means and standard deviations reported in columns are for fathers.

p .05

p < .01.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the families for their participation in the project. Work on this project was supported by NIMH grant R01-MH68920.

References

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology. 1971;4:1–103. doi: 10.1037/h0030372. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman LR. A person-centered approach to adolescence: Some methodological challenges. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2001;16:28–53. doi: 10.1177/0743558401161004. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Shannon JD, West J, Brooks-Gunn J. Parental interactions with Latino infants: Variation by country of origin and English proficiency. Child Development. 2006;77:1190–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00928.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Eyberg SM. Self-reported parenting practices in Dominican and Puerto Rican mothers of young children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:354–363. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_07. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Fernandez Y, Cortes DE. Incorporating the cultural value of respeto into a framework of Latino parenting. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:77–86. doi: 10.1037/a0016071. doi: 10.1037/a0016071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada EJ, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Yoshikawa H. Familismo in Mexican and Dominican families from low-income, urban communities. Journal of Family Issues. 2012 Advanced online publication. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12460218. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson VJ, Harwood RL. Attachment, culture, and the caregiving system: The cultural patterning of everyday experiences among Anglo and Puerto Rican mother–infant pairs. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24:53–73. doi: 10.1002/imhj.10043. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK, Otsuki-Clutter M. Racial and ethnic differences: Sociocultural and contextual explanations. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:47–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00714.x. [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, McBride C, Briones E, Kurtines W, Szapocznik J. Ecodevelopmental correlates of behavior problems in young Hispanic females. Applied Developmental Science. 2002;6:126–143. doi: 10.1207/S1532480XADS0603_3. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ. Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:685–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Santiago M, Ramirez-Garcia JI. ?Hay que ponerse en los zapatos del joven?: Adaptive parenting of adolescent children among Mexican-American parents residing in a dangerous neighborhood. Family Process. 2011;50:92–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01348.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech Rodríguez MM, Donovick MR, Crowley SL. Parenting styles in a cultural context: Observations of “protective parenting” in first-generation Latinos. Family Process. 2009;48:195–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01277.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll AK, Russell ST, Crockett LJ. Parenting styles and youth well-being across immigrant generations. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:185–209. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07307843. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert NC. The Hispanic population: 2010. U. S. Census; Washington, DC: 2011. 2010 Census Briefs No. C2010BR-04. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF. How families manage risk and opportunity in dangerous neighborhoods. In: Wilson WJ, editor. Sociology and the Public Agenda. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 231–238. doi: [Google Scholar]

- García Coll G, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, McAdoo HP. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01834.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia F, Gracia E. Is always authoritative the optimum parenting style? Evidence from Spanish families. Adolescence. 2009;44:101–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser C, Lehmann W, Eid M. Separating “rotators” from “nonrotators” in the mental rotations test: A multigroup latent class analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2006;41:261–293. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4103_2. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4103_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Coxe S, Roosa MW, White RMB, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Saenz D. Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican-American adolescents' mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9366-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth LC, Ispa JM, Rudy D. Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development. 2006;77:1282–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood R, Leyendecker B, Carlson V, Asencio M, Miller A. Parenting among Latino families in the US. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting Volume 4: Social Conditions and Applied Parenting. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa MW. Parenting and family socialization strategies and children's mental health: Low–Income Mexican–American and Euro–American mothers and children. Child Development. 2003;74:189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents' ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian TW, McKenry PC, McKelvey MW. Cultural variations in parenting: Perceptions of Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic, and Asian-American parents. Family Relations. 1994;43:30–37. doi: 10.2307/585139. [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Nair RL, Knight GP, Roosa MW, Updegraff KA. Measurement equivalence of neighborhood quality measures for European American and Mexican American families. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37:1–20. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20257. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, Boyd BM. The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds DD, Germán M, Deardorff J, Updegraff KA. The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Virdin LM, Roosa MW. Socialization and family correlates of mental health outcomes among Hispanic and Anglo American children: Consideration of cross-ethnic scalar equivalence. Child Development. 1994;65:212–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00745.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamborn SD, Mounts NS, Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM. Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development. 1991;62:1049–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letiecq BL, Koblinsky SA. Parenting in violent neighborhoods: African American fathers share strategies for keeping children safe. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:715–734. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03259143. [Google Scholar]

- Livas-Dlott A, Fuller B, Stein GL, Bridges M, Figueroa AM, Mireles L. Commands, competence, and cariño: Maternal socialization practices in Mexican American families. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:566–578. doi: 10.1037/a0018016. doi: 10.1037/a0018016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. doi: 10.1093/biomet/88.3.767. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Martin JA. Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development. Wiley; New York: 1983. pp. 1–101. doi: [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user's guide. 6th ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Niar RL, White RMB, Roosa MW, Knight GP. Cross-language measurement equivalence of parenting measures for use with Mexican American populations. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:680–689. doi: 10.1037/a0016142. doi: 10.1037/a0016142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Ruiz M. Does familism lead to increased parental monitoring?: Protective factors for coping with risky behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16:143–154. doi: 10.1007/s10826-006-9074-5. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Liu F, Torres M, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Saenz D. Sampling and recruitment in studies of cultural influences on adjustment: A case study with Mexican Americans. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.293. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LG, Conger RD. Linking mother-father differences in parenting to a typology of family parenting styles and adolescent outcomes. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28:212–241. doi: 10.1177/0192513X06294593. [Google Scholar]

- Small SA, Kerns D. Unwanted sexual activity among peers during early and middle adolescence: Incidence and risk factors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:941–952. doi: 10.2307/352774. [Google Scholar]

- South SJ, Crowder K, Chavez E. Exiting and entering high-poverty neighborhoods: Latinos, Blacks, and Anglos compared. Social Forces. 2005;84:873–900. doi: 10.1353/sof.2006.0037. [Google Scholar]

- Stattin H, Kerr M. Parental monitoring: A reinterpretation. Child Development. 2000;71:1072–1085. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele RG, Nesbitt-Daly JS, Daniel RC, Forehand R. Factor structure of the parenting scale in a low-income African American sample. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:535–549. doi: 10.1007/s10826-005-7187-x. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Mounts NS, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM. Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment across varied ecological niches. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1991;1:19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Suro R, Kocchar R, Passel J, Escobar G, Tafoya S, Fry R, Wunsch M. The American community - Hispanics: 2004. U. S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2007. No. ACS-03. [Google Scholar]

- Tein J-Y, Coxe S, Cham H. Statistical power to detect the correct number of classes in latent profile analysis. Structural Equation Modeling. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2013.824781. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, Enders CK. Identifying the correct number of classes in growth mixture models. In: Hancock GR, Samuelsen KM, editors. Advances in Latent Variable Mixture Models. Information Age; United States: 2007. pp. 317–341. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino families. In: Peterson GW, Bush KR, editors. Handbook of Marriage and Family. 3rd ed. Springer; New York: 2012. pp. 723–247. [Google Scholar]

- Varela RE, Vernberg EM, Sanchez-Sosa JJ, Riveros A, Mitchell M, Mashunkashey J. Parenting style of Mexican, Mexican American, and Caucasian-non-Hispanic families: Social context and cultural influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:651–657. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.651. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Deardorff J, Gonzales NA. Contextual amplification or attenuation of pubertal timing effects on depressive symptoms among Mexican American girls. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50:565–571. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.006. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Roosa MW. Neighborhood contexts, fathers, and Mexican American young adolescents' internalizing symptoms. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:152–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00878.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Roosa MW, Weaver SR, Nair RL. Cultural and contextual influences on parenting in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:61–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00580.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White RMB, Roosa MW, Zeiders KH. Neighborhood and family intersections: Prospective implications for Mexican American adolescents' mental health. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:793–804. doi: 10.1037/a0029426. doi:10.1037/a0029426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]