Abstract

We address a long hypothesized relationship between the proximity of individuals' dwelling units and their kinship association. Better understanding this relationship is important because of its implications for contact and association among members of a society. In this paper, we use a unique dataset from Nang Rong, Thailand which contains dwelling unit locations (GPS) and saturated kinship networks of all individuals living in 51 agricultural villages. After presenting arguments for a relationship between individuals’ dwelling unit locations and their kinship relations as well as the particulars of our case study, we introduce the data and describe our analytic approach. We analyze how kinship - considered as both a system linking collections of individuals in an extended kinship network and as dyadic links between pairs of individuals -patterns the proximity of dwelling units in rural villages. The results show that in general, extended kin live closer to one another than do unrelated individuals. Further, the degree of relatedness between kin correlates with the distance between their dwelling units. Close kin are more likely to co-reside, a fact which drives much of the relationship between kinship relatedness and dwelling unit proximity within villages. There is nevertheless suggestive evidence of a relationship between kinship association and dwelling unit proximity among kin who do not live together.

A large literature examines co-residence patterns of close kin as a measure of the structure of family organization (Le Play 1884; Wirth 1938; Parsons 1943; Parsons and Bales 1955; Linton 1959). Because of data limitations, however, little attention has been given to the spatial proximity of close kin living in different dwelling units, or to the geographical patterning of more weakly related kin. Looking beyond household co-residence and beyond the kinship ties of closely related individuals has the potential to offer valuable insight into the structure of the family and extended kin groups as well as the role that kinship might play in reinforcing proximity effects on interaction. It also informs the coincidence of social and spatial distance more generally. A more thorough understanding of the mechanisms underlying the relationship between dwelling unit proximity and kinship is important because of its implications for contact and association among members of a society.

This paper explores the relationship between dwelling unit proximity and kinship in agricultural villages in Nang Rong, Northeast Thailand. As we discuss in the next section, the literature tends to view spatial proximity as a factor affecting social ties, but it is also likely that social ties—in this case, kin ties—influence spatial arrangements. To explore the spatial patterning of kin ties, we use a unique dataset that contains dwelling unit locations (GPS) and saturated kinship networks of over 50,000 individuals from 51 villages in Nang Rong. After introducing the data, we describe our approach to constructing a data set of person-to-person dyads in each village. Each dyad is characterized by residential proximity and the closeness of the kin tie involved. In the analysis, we use a variety of descriptive techniques to explore the relationship between kinship association and dwelling unit proximity within villages and how these patterns vary between villages. We take two approaches, one focusing on extended kinship groups and the other on dyads of varying degrees of kinship relatedness.

Background

Studies of the association between spatial proximity and social networks have most often viewed spatial proximity or other features of the environment as affecting the likelihood of social ties between individuals. Festinger, Schachter, and Back’s (1950) classic study found that friendships in a graduate student housing community were closely related to the proximity of apartments. Similarly, Coombs (1973, 1975) found that apartment orientation and visibility affected the likelihood of exchange of babysitting between residents. Hipp and Perrin (2009) found that physical distance decreased the probability of both strong and weak ties in a neighborhood. Similarly, Mouw and Entwisle (2006) found that the likelihood of friendship within middle, junior high, and high schools depended to some extent on the proximity of student residences. The relationship between spatial proximity and social ties holds both at very close ranges, such as conversations in small groups (Hare and Bales 1963) and at more variable distances, as seen in Latané et al.’s findings on the diminishing strength of social influence with increasing spatial distance (Latané et al. 1995). In all cases the likelihood of social interaction or social ties falls with increasing distance, though the rate of decline depends on the kind of social relationship (Butts 2002). Indeed, it has been demonstrated that even modest distance-decay functions in likelihoods of tie formation can account for the vast majority of the occurrence of social ties in large-scale networks (Butts 2003).

The influence of people's spatial locations on their opportunities for interaction has long been acknowledged in the theoretical literature. Peter Blau's 1974 Presidential Address to the American Sociological Association lists place of residence as an exemplary parameter determining the forms of social structure (Blau 1974: 617). In another, older line of research, much of the concern with residential segregation has been based on its implications for contact and association between groups which live apart (cf. Park 1926; Duncan and Lieberson 1959; Duncan and Duncan 1955). The idea behind this hypothesized association is perhaps best put in terms of Tobler's 'first law of geography': "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things" (Tobler 1970).

Although many studies have examined the form of the relationship between spatial proximity and social ties, few have explicitly mapped social networks using specific geographical locations. Social ties between dyads have been mapped - for example husband’s and wife’s residential locations prior to marriage (Morrill and Pitts 1967) or locations of survey respondents and their political discussion partners (Baybeck and Huckfeldt 2002) – but geographic referencing of complete networks is quite rare. The early community studies of Loomis and colleagues are notable exceptions. Loomis (1941) provided a village map of houses and buildings along with visiting relations between families in El Centro, New Mexico, and Loomis and Davidson mapped house locations and acquaintanceship between residents in the newly formed community of Dyess Colony, Arkansas (Loomis and Davidson 1939). For more recent exceptions, Mouw and Entwisle (2006) used spatially referenced information about complete friendship networks to examine the relationship between residential segregation and social segregation in schools, Grannis (2010) mapped neighborly relations in several communities, and researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have integrated locational data drawn from cellular phones with standard network surveys (Eagle, Pentland and Lazer 2009; Raento, Oulasvirta and Eagle 2009). At a larger scale of social organization, Faust et al. (1999) mapped the provision of agricultural help, movement of elementary and secondary school students, and travel of daily labor between villages in Nang Rong, Thailand.

This paper uses unique data on complete networks from rural Thailand to examine spatially referenced kin networks. In contrast to a literature largely focused on social interaction as a consequence of spatial proximity, when kin ties are the focus, the relationship between social and spatial proximity can reflect a reverse direction of effect. That is, though it is clear that propinquity of residence bears some influence on kinship affiliations - for instance, through the choice of marriage partners (cf. Kennedy 1943) - we assert that preferences and choices about where to live are also influenced by proximity to kin. These decisions, in turn, have consequences for the form and frequency of contact between kin as well as the role of kin in social and economic life more generally. While a large body of literature (e.g., Ruggles 1986, 1988, 1990, 1994, 1996, 2007; Ruggles and Goeken 1992; Soldo 1981) has debated the decline of families as an organizing principle historically, and currently in the developing world (e.g., Ruggles and Heggeness 2008), such work has focused narrowly on household co-residence of strongly connected kin, while ignoring the possibility of residing nearby in a separate dwelling unit. These studies provide limited understanding of the residential choices made by individuals and consequently have painted an incomplete picture of kinship integration in communities, especially with respect to integration of extended kin groups and variability in the closeness of kinship relationships.

The availability of spatially referenced complete networks replicated over 51 communities for Nang Rong, Thailand enables us to look at the coincidence of social and spatial proximity in new ways. In this paper, we use spatially referenced kin networks to address interrelated questions regarding the relationship between kinship association and residential proximity within villages. Do members of the same extended kinship group tend to live closer to each other than members of different extended kinship groups? Do these patterns differ by type of extended kinship group - specifically, whether it does or does not contain "relinking" of the sort given prominence in anthropological analyses of endogamous marriage systems (cf. Weil 1949; White and Jorion 1992, 1996)? In general, we expect a positive correlation between the closeness of the kin tie and the proximity of dwelling units. If this is true, is it because closely related kin (e.g., parents, children, siblings and spouses) are more likely than more distantly related kin to live within the same dwelling unit? Might it also be due to the fact that when closely related kin live apart, they tend to live closer to each other than to unrelated individuals?

To address these questions, we simultaneously consider the spatial distribution of dwelling unit proximity and the network distribution of kinship distance in a dataset of approximately 25,000 individuals living in 51 villages in Nang Rong1. Earlier research on Nang Rong has shown that there is substantial variation from one village to the next in the patterning of kin ties (Entwisle et al. 2007). We expect variation in the spatial arrangements of dwelling units as well, reflecting cultural and demographic patterns in addition to the unique history and geographic circumstances of each village.

Case Study: Nang Rong, Thailand

Nang Rong district is a rural, primarily rice-growing region located in Northeast Thailand. The district is the approximate size of a typical county in the Eastern United States (1300 km2). In contrast to the American Midwest, where historically, families lived on their land and dwellings were dispersed over the landscape, villages in Nang Rong are clusters of dwellings surrounded by agricultural lands more similar to the arrangement of small towns in rural Europe or New England. A few villages date back hundreds of years to when the region was part of the Angkor empire, but most settlement occurred during the 20th century when large numbers of migrants arrived from other parts of the country and settled close to promising lands for rice cultivation, especially after World War II (Entwisle et al. 2008a). Because the region's agricultural production depends on monsoonal rains, small differences in elevation were consequential with respect to risks from flooding or drought. The shape of the residential clusters within villages reflects this local topographic variation. Once settled, land around a cluster of dwellings was converted to cultivation in a pattern radiating out from the village, influenced by topography but also the spatial distribution of soils, presence of streams and rivers, and the like (Entwisle et al. 2008b).

The villages in Nang Rong are fairly small. In 2000, they ranged from 333 to 1,260 residents with a median of 6402. Houses are generally close to each other. Considering all dwelling unit to dwelling unit dyads, the median distance between dwelling units within a village ranges from 176 to 1,501 meters3. Given this, villagers tend to know one another. Historically, houses in Nang Rong were built on stilts, with daily tasks such as food preparation occurring in the open area underneath the dwelling unit; sleeping and storage of household possessions occurred in the enclosed area above. Leisure time was also spent under the house, conversing with relatives, friends, and neighbors. More recently, villagers have enclosed the bottom story, either during new construction or as a modification, with leisure activities increasingly taking place behind the walls of the dwelling unit (Rindfuss et al. 2007). These changes reflect a number of factors, including an increase in the general economic well-being and a preference to watch television, which is almost universally an indoor activity.

As Nang Rong was a frontier area for new settlement until about the 1960s, spatial arrangements within villages today likely reflect the choices made by the initial migrants to the area and the availability of suitable land for agriculture and dwelling units, compounded over subsequent generations. The settlers traveled in small groups, most likely of kin, and seem to have settled close to one another upon arrival (Phongphit and Hewison 2001), with their dwelling units clustered on high(er) land protected from flooding. As time passed and new generations moved out of their natal households, those staying in the village were likely to construct dwelling units close by. Although there are plenty of exceptions (Chamratrithirong et al. 1988; Foster 1975: 35), a common pattern in rural Thailand is for a newly married couple to reside with the bride’s parents initially, later constructing their own dwelling unit next door, provided there is sufficient available land. In the ideal-typical pattern, the youngest daughter remains with the parents to care for them in their old age and inherits the parents’ house and possessions; other children get a share of the land but must build their own dwelling units. Over generations, this cultural pattern of married children remaining near their parents would create positive relationships between closeness of kin and closeness of dwelling units within the villages. But, of course, it depends on the availability of suitable land, as Foster (1978) has shown for elsewhere in rural Thailand. If no nearby land were available, the couple would need to locate at the edge of the settlement, or else migrate from the village. For these reasons, within villages, we expect a positive relation between the closeness of kin ties and the proximity of the dwelling units in which those kin reside.

Thai kinship is bilateral, with kinship calculated through both father and mother (Foster 1975). Marriage partners are largely a matter of personal choice rather than parental arrangement. Marriage is prohibited with first and perhaps second cousins and “frowned upon” with any person of known genealogical relationship (Foster 1975: 36).

To give readers a better sense of the study area and our data, Table 1 shows the distribution of village characteristics along four dimensions. The numbers of resident individuals and households show just how small the villages are. Migration of young people from the region is quite common: looking at migration prevalence, which records the percentage of those under age 45 who resided in the village in 1984 and lived outside of the village in 1994, one can see that somewhere between a third and a half of young people move away. Such migration patterns have hollowed out the middle of the age distribution and increased dependency ratios4. While the out-migration stream is primarily composed of young individuals, it is not overwhelmingly male, a feature which makes Nang Rong stand out from many migrant-sending areas around the world. The settlement of the region occurred recently. The demographic variables reported in Table 1 also reflect the region’s recent population growth and historical underdevelopment, as even the residents who do not migrate are relatively young. Few of those older than 15 have been educated beyond primary school. Of course, most villagers between the ages of 15 and 50 have been or are married.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 51 Nang Rong study villages

| Mean | Min. | 25th % | Median | 75th % | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village demographicsa | ||||||

| N households | 182.83 | 86 | 151 | 173 | 201 | 324 |

| N individuals | 672.51 | 333 | 563 | 640 | 771 | 1260 |

| N migrants | 240.80 | 125 | 190 | 243 | 276 | 450 |

| Migration prevalence, 1984–94 | 43.73 | 30.08 | 38.25 | 43.18 | 48.20 | 60.64 |

| % female residents | 51.91 | 49.29 | 50.71 | 51.81 | 52.81 | 57.60 |

| % ever married | 71.41 | 64.15 | 68.18 | 71.80 | 74.22 | 78.25 |

| % educated past primary school | 20.24 | 8.37 | 17.01 | 20.05 | 23.72 | 28.97 |

| Mean age of residents | 30.92 | 27.42 | 29.83 | 30.99 | 32.01 | 35.03 |

| Mean age of migrants | 28.49 | 26.28 | 27.60 | 28.41 | 29.36 | 30.81 |

| Elderly dependency ratio | 11.61 | 6.23 | 9.91 | 11.26 | 12.93 | 16.83 |

| Youth dependency ratio | 29.05 | 24.75 | 27.00 | 28.72 | 30.61 | 35.46 |

| Year village formally founded b | 1922 | 1793 | 1900 | 1914 | 1955 | 1984 |

| Economic characteristics c | ||||||

| Rai of agricultural land (100s) | 28.69 | 4.85 | 21.00 | 24.79 | 31.61 | 121.38 |

| % land used to grow rice | 81.09 | 30.00 | 70.49 | 83.52 | 95.00 | 100.00 |

| % land used to grow cassava | 5.71 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 56.77 |

| % households grow rice | 87.98 | 30.00 | 85.06 | 92.00 | 95.27 | 100.00 |

| % households grow cassava | 4.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 26.88 |

| Village social life c | ||||||

| N public telephone booths | 0.76 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| N cell phones | 2.04 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 12 |

| N public use wells in village | 6.14 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 42 |

| Spatial arrangements d | ||||||

| Mean meters between dwellings | 607.39 | 215.59 | 334.52 | 504.02 | 781.26 | 2473.17 |

| Median meters between dwellings | 477.00 | 175.79 | 271.88 | 400.84 | 560.00 | 1500.71 |

Notes:

data from the 2000 individual survey;

data from administrative records tracing back to original foundation and eliminating double counts;

data from the 2000 community survey;

data from the 2000 spatial survey.

Economically, Nang Rong is an agricultural area, with almost all households growing rice. A few villages grow significant amounts of cassava as a cash crop, but this practice is rare in the study villages we examine and, for the most part, geographically confined to the southwestern portion of the district. At the same time, the amount of land within the administrative boundaries of each village under cultivation is quite small – the mean is 2,869 rai5, about 459 hectares. The social lives of villagers are dominated by interactions within the village, such as those that take place between farmers of adjacent fields or in town (Entwisle et al. 1996). Contact with migrants is not infrequent – indeed, many come home annually to help with the rice harvest or attend festivals and weddings (Entwisle et al. 2010) – but it is not an everyday occurrence. At the time of the 2000 data collection, there were few cell-phones in the villages and a significant number of villages (>25%) did not have a single working telephone booth. In contrast to the densely nucleated clusters of residences, villages are spread apart, suggesting that the villages are relatively isolated and most quotidian interaction will be between members of the same village. Qualitative interviews described in Entwisle et al. (1996) have shown this to be the case.

Data

In this paper, we use data from the Nang Rong Projects’ 2000 wave of data collection (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/nangrong), which, in addition to collecting sociodemographic information on individuals, households, and villages, contained two design elements crucial for our purposes. One is the collection of saturated social network data (Rindfuss et al. 2004; Entwisle et al. 2007). All individuals in a sample of 51 villages were enumerated within households and then linked to network affiliates. Here, we focus on kin networks. Another important design element was the collection of geospatial data, including the locations of dwelling units (Rindfuss et al. 2003). Dwelling units and their locations were linked to households and their members. Both types of data were collected within the boundaries of the 51 administrative villages that have been the focus of attention since the study’s inception in 1984. These 51 villages represent approximately one-quarter of all villages in Nang Rong.

Studying the interrelationships between spatial and social networks requires setting boundaries for the analysis, where ties to people and locations outside the boundary are not considered (Laumann et al. 1992). With respect to geography, it is important to set appropriate scale. The particulars of our study area make these choices easy: since social life is dominated by interactions within the village and the villages are predominantly nucleated clusters of dwelling units surrounded by agricultural lands, we restrict our analyses to dwelling units within the boundaries of the village and kinship relations to those that exist between village residents (also see notes 6, 7 and 10). Doing so helps isolate community-level patterns of kinship distance and dwelling unit proximity as they bear on the day-to-day experiences of individuals. Inter-village visitation and communication with migrants in Bangkok are important elements of social life in Nang Rong, but our focus in this paper is local.

Approach

We take two approaches to the study of kinship networks; one is global and focuses on extended kinship groups, the other is local and pertains to kinship dyads of differing degree. The system-oriented or global network perspective follows a classic anthropological approach to kinship (e.g., Weil 1949) and examines whether dwelling unit distances are closer, on average, between individuals in a given extended kinship group than between individuals in separate extended kinship groups. We expect those in the same extended kinship group to live closer to each other, on average, than those in different groups. Whether this relationship is entirely driven by a tendency for kin to live together is an open question, however, and we investigate it below.

Studies of kinship have a long history in anthropology and have evolved considerably over the decades. One stream of this recent work has focused on characterizing patterns in endogamous kinship systems through marital “relinking” of kinship over generations (Hamberger 2011; Nooy et al., 2005; White and Jorion 1992, 1996). A kinship group is said to relink when a marriage occurs between two individuals who share a common ancestor. The presence of marital relinking creates semicycles in extended kinship groups and might be associated with greater structural cohesion. Thus, a key question with respect to the relationship between system-level kinship groups and spatial proximity is whether or not members of groups which contain relinking live closer to each other than members of groups which do not contain relinking. Though marital relinking of kinship groups is not common in Nang Rong (as we document below), we evaluate this question.

Our second approach to the study of kinship is individual and dyad-centered - that is, individuals in relation to every other individual within the village. To do this, we calculate kinship distances between pairs of individuals as the shortest number of spousal and parent-child ties between them; we describe this approach in greater detail below. Doing so allows us to examine the properties of individuals' kinship networks and to make aggregate statements about the spatial distribution of kinship relations of different degrees.

These two approaches provide complementary perspectives on the association between kinship and spatial proximity, and each has advantages and limitations for our particular case, which we discuss in the concluding sections of the paper.

Methods

To construct kin networks, we use data on the identity and locations of mothers, fathers, siblings and spouses collected as part of the household surveys6. Combining the social network and locational data enables us to create 51 datasets of all person-to-person dyads within each of the 51 study villages. Each dyad has information about both the geographic and kinship distance between two individuals. With this we are able to examine spatially referenced kin networks and to assess relationships between individuals’ closeness of kin association and the distances between their dwelling units within each village.

Direct within-village ties to mothers, fathers, and spouses were enumerated for each individual. The data linking children to parents was turned into 51 Nv × Nv matrices Cijv, where i indexes the village-specific unique identification number of individuals represented by the rows of the matrix, j indexes the unique identification number of the individuals represented by its columns, and v indexes the village to which it corresponds. Within village v, if village resident i was a child of village resident j, then a value of 1 was entered into the ijth cell of the matrix Cv; otherwise a value of 0 was entered in this space. With each C matrix, we defined a parent to child matrix P, which, in the same fashion, records whether the ith resident of village v is a parent of village v’s jth resident. Note that P equals CT where the superscript T denotes the transpose operator. In addition to the C and P matrices, we defined matrix E which indicates all ever-recorded (in any wave of data collection) spouse-to-spouse links. An important note is that while matrix E is symmetric in that the value of cell ij equals the value of cell ji, the matrices C and P are asymmetric, being transposes of each other. The identification of unique spouse and parent-child dyads allows us to construct extended kinship networks within the Nang Rong villages.

From these basic kin matrices we created higher order links between individuals following the logic of Batagelj and Mrvar (2008). All of these are built from the first order kinship matrix K, which is defined as the sum of C+P+E, which gives first degree kin ties. For our system-oriented analyses using extended kinship groups, we take all N-1 powers of K and convert to binary numbers, where N is the number of rows (individuals) in the matrix. This is analogous to finding the weakly connected components of the kinship network. We call the resultant matrix W to reflect this. Non-zero entries in W indicate that two individuals are in the same extended kinship group. Our system-oriented approach examines the spatial distribution of extended kinship networks using the W matrices. Aggregated across villages, 31.4% of the components we found were unconnected individuals, the median component size was 5, and the largest component we found contained 750 individuals7. Figure 1 graphs the relationship between the component size distribution and the number of components for kin groups that do and do not have observed relinking (the calculation of which is discussed in the next paragraph).

Figure 1.

Log-log plot of extended kin group size distribution and number of extended kin groups across all villages, by whether or not the component contains relinking.

Marital relinking in the extended kinship network would be evidenced by semi-cycles in a reduced form of the extended kinship matrix that eliminates semi-cycles formed through spouses. We checked this by taking each of the N-1 powers of the first-order transition matrix P (parent to child ties), and summing each of the resultant matrices together. Using only the P matrix eliminates the need to exclude semi-cycles due to spousal relations8. These operations give the number of directed walks from the person represented by row i to the person represented by column j (Wasserman and Faust 1994). Values higher than 1 indicate an observed semi-cycle in the kinship network, showing who is reachable through multiple lines of descent from a single individual. Those belonging to an extended kinship group that contains semi-cycles are considered members of a relinking component. As shown in Figure 1, there are not many extended kinship groups wherein we observe relinking, but those with relinking tend to be larger than those without. Note that 12 of the 51 villages we analyze do not have observed relinking.

For our individual-oriented analyses, we look at how the degree and type of kinship relations between pairs of individuals pattern the distances between their respective dwelling units. Thus, we find people who are connected as second degree kin but not first degree kin by multiplying K by itself, converting the product to binary numbers such that positive off-diagonal numbers are equal to 1 and all others are equal to zero, subtracting the matrix K (first-degree kin) and again converting to binary numbers. We find the third degree kin in a similar fashion, except that we subtract the second degree kin matrix in addition to the first. And so on for the fourth degree kin. All kin matrices were then multiplied by the scalar representing which shortest kinship degree connected the individuals that it indexed and were summed to create a matrix representing the kinship distances between all relevant kin (A). Because of the compounding of relations, missing data are more serious for higher degree ties than lower degree ties.9 After computing the kinship relations among all persons ever enumerated in the Nang Rong surveys, we restricted our sample to those living in the villages at the time of the 2000 data collection who we were able to link to the spatial data (see note 10 below).

Closeness of kin tie is measured in terms of kin degree. We follow White and Moody (2003) building on the ideas of White (1963) and use this approach rather than enumeration of specific kin-types to circumvent biases that may arise from using American conceptions of kinship in a different cultural context. To show how this measure corresponds with common American kinship terminology, Figure 2 uses kin degree to describe ego’s place within a hypothetical kin group. First degree kin ties link ego to a mother, (deceased) father, husband, son, and daughter. Second degree kin ties link to a mother- and father-in-law, step-father, brother, half-brother, and grandparents. Third degree kin ties link to a sister-in-law, niece, and aunt in this illustration, and fourth degree ties to a cousin and an uncle. In addition to matrices describing kin degree, we defined matrices to reflect specific kinship types (such as sibling) among first- and second-degree kin ties as part of our individual-oriented analyses. These were gathered into the matrix R which indicates the specific relations (e.g., spouse, parent, sibling, grandparent) between individuals with numerical codes. Among first-degree ties, spatial relationships depend on whether it is a parent-child or spousal dyad. Second-degree kin ties collect together potentially diverse kin, and spatial relationships may vary within this category as well as in comparison with third- and fourth-degree kin ties. We examine this variation below.

Figure 2.

Hypothetical kin group

Notes: Triangles represent males, circles females, equals signs marriages, horizonal lines siblings, and vertical lines descent or parentage. Numbers show kinship degree distance from ego with standard American terms of kinship from ego's perspective provided to increase clarity. The dashed diagonal line indicates that the father is deceased.

Within the 51 Nang Rong villages, the specific locations of all residential structures were determined using global positioning system (GPS) devices by a spatial survey team and then linked to the households which occupied them. Distances in meters between all households’ dwelling units within a village were calculated using the point-to-point distances feature in Hawth’s tools (Beyer 2004) available for Arc-GIS. With these tools we created 51 within village M × M (household by household) distance matrices (Dijv) where the ijth cell of village v represents the Euclidean (“as the crow flies”) distance from household i to household j. These distances are necessarily symmetric such that the distance from household i to household j equals the distance from household j to household i. All cells have a value representing the distance between the households indexed by the respective rows and columns, and all distances between households and themselves (i.e., the cells along the main diagonal of the matrix) are valued 0.

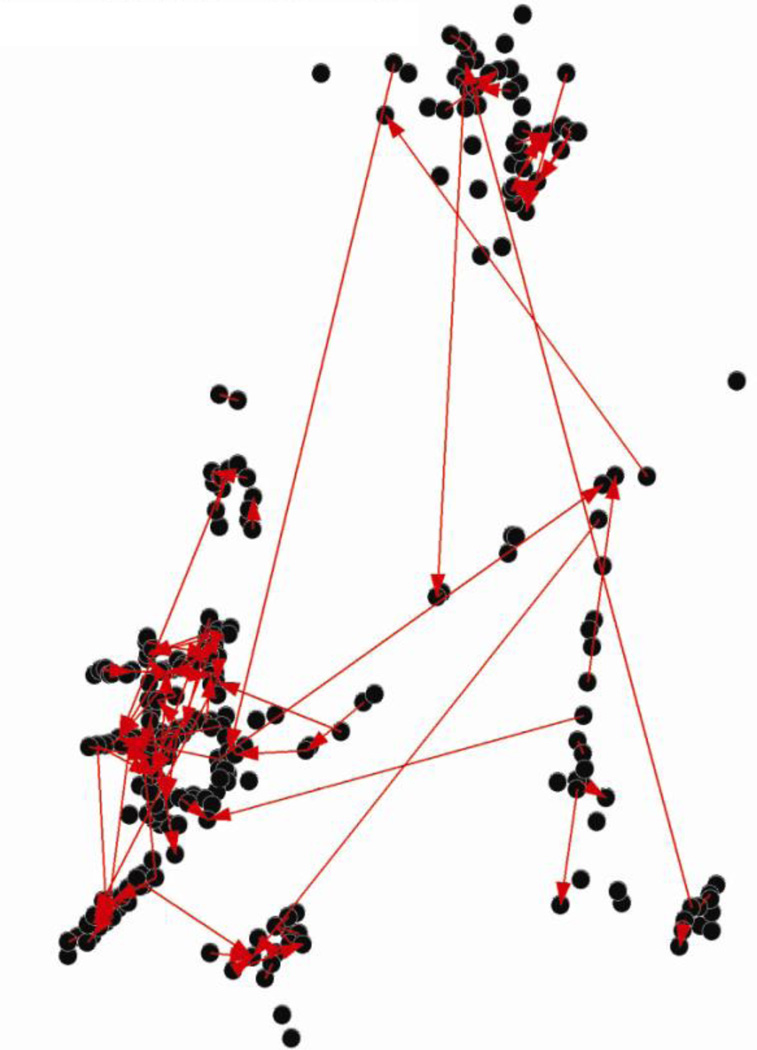

To illustrate how spatial data are informative about the patterning of kin ties in Nang Rong, Figures 3–5 show maps of child-to-parent links among households in three villages. Dots indicate dwelling unit locations. Arrows point from child households to the parent households. Co-residence is not shown in these figures. The question here is whether children tend to live close to their parents when they do not live together. The village in Figure 3 is most easily viewed. There are 164 households and 65 child-household to parent-household ties. Dwelling units are well distributed. Households with parents are somewhat centrally located, with dwelling units housing children more peripheral, a pattern we expect based on our above discussion of how cultural preferences might be expressed over several generations. The mean distance between all dwelling units in Figure 3 is 431 meters; between dwelling units linked by child-parent ties the mean is 213 meters. The village in Figure 4 consists of 201 households and 123 child household to parent household ties. This village is organized around dwelling unit clusters, and child-to-parent ties are denser within clusters than between them. The mean distance between all dwelling units is 1434 meters and is 740 meters between dwelling units linked by parent child ties. The village in Figure 5 consists of 267 households and 131 ties. It is also organized around dwelling unit clusters, but in contrast to Figure 4, there are plenty of ties between as well as within these clusters. The mean distance between all dwelling units is 1158 meters and between dwelling units linked by parent child ties it is 239 meters. Although the three villages vary in the density and shape of the patterns shown, taken together, they suggest a possible correspondence between social and spatial proximity, which we examine in further analyses for the entire set of 51 villages. Other villages display equally complex arrays of sociospatial patterning.

Figure 3.

Map of child to parent household linkages in village A.

Figure 5.

Map of child to parent household linkages in village C.

Figure 4.

Map of Child to Parent Household Linkages in Village B.

In Figures 3–5, there is potential for multiple ties depending on residential arrangements in the village (e.g., a co-resident husband and wife might both have parents as well as siblings living in the village). Because the dwelling unit distance matrices were measured at the household level and our kinship distances matrices were measured at the individual level, we needed to convert them to the same units of observation, individuals. We did this in two steps. First, we defined an N × M (individuals by households) matrix Hijv where cell ij in village v is valued 1 to represent whether individual i was a member of household j and is valued 0 otherwise. Second, with this matrix we found the individual to individual matrix of dwelling unit distances by taking the binary solution to this equation: U = HDHT. This conversion process yielded a matrix representing the distance between the dwelling unit of person i and the dwelling unit of person j. If individuals i and j lived in the same household, the distance between their households was 0.10

We now have the four matrices on which our analyses are based: matrix W which indicates whether individuals are in the same extended kinship group (weakly connected component) or not; matrix A which represents the degree of the kin relationship between individuals; matrix R which represents the specific subtype (if any) of first and second degree ties between individuals; and matrix U which represents the distance between their respective dwelling units. After removing self-links, converting to long (edgelist) format, and merging the four matrices together, we have a dataset enumerating all within-village dyadic relations between individuals in the sample, with a binary variable representing whether they are extended kin, a continuous variable representing their dwelling unit distance, an ordinal variable representing their kinship distance, and a nominal variable representing the specific subtype of first or second degree relation (if any) between them. There are 51 of these datasets corresponding to the 51 villages.

Results

We begin our discussion of the relationship between kinship and dwelling unit proximity in Nang Rong with results from a system-oriented analysis of whether or not distances between dwelling units are closer within extended kin groups than between them. From there, we present results from our individual-oriented analyses, which, we argue, add significant value to the insights taken from the system-oriented approach.

System-oriented

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics across the distribution of 51 villages for average (mean and median) dwelling unit distance within kinship groups and between them. It contains two sections, the top shows the averages calculated including co-resident kin (who have dwelling unit distances of zero), while the bottom shows the averages calculated on all kin except those who are co-resident. The general pattern is quite clear, no matter how average is operationalized or whether co-resident kin are included or excluded: dwelling units tend to be closer to each other within kinship groups than between them.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics across villages of mean and median distances in meters within and between kinship groups

|

Including co-resident kin (N=51) | |||||

| Mean distances | Min. | 25th Pct. | Median | 75th Pct. | Max |

| Within kin groups | 152 | 277 | 398 | 652 | 1934 |

| Between kin groups | 205 | 335 | 511 | 762 | 2850 |

| Median distances | |||||

| Within kin groups | 86 | 233 | 334 | 486 | 1538 |

| Between kin groups | 173 | 266 | 397 | 536 | 1624 |

|

Excluding co-resident kin (N=51) | |||||

| Mean distances | |||||

| Within kin groups | 182 | 329 | 443 | 680 | 2384 |

| Between kin groups | 205 | 335 | 511 | 763 | 2851 |

| Median distances | |||||

| Within kin groups | 159 | 264 | 370 | 539 | 1546 |

| Between kin groups | 173 | 266 | 397 | 356 | 1624 |

We were also interested in whether these differences are real or could have been generated by random processes. Using matrix permutation tests within each village, we examined whether the relationships between dwelling unit distances within and between extended kin groups were different than would be expected at random given the spatial distribution of dwelling units and the size and number of extended kin groups in each village. Thus, based on our hypotheses about these relationships, we compare the proportion of the differences between the average dwelling unit distance within kin groups relative to the average dwelling unit distance between them to the distribution of these differences in random permutations. The statistic for comparison of means is:

| (1) |

, where uij is the distance between individuals i and j, and wij equals 1 if i and j are in the same extended kinship group and 0 otherwise; summation is within a village. The null hypothesis is that the observed difference (within-group average minus between-group average) is not smaller than the difference found by chance. 1,000 permutations were computed for each test in each village. We use five percent (i.e., p ≤ 0.05 or 50 permutations) as a cutoff for what we call significantly shorter distances than random in kinship groups than between them.

For mean distance, with and without co-resident kin, we found that distances within kinship groups are significantly smaller than between them (i.e., rejected the null hypothesis) in 34 (with co-resident) and 42 (without co-resident) of the 51 villages. For median distance we rejected the null hypothesis in 35 villages when co-resident kin were included and 40 when coresident kin were excluded. We take this as strong evidence that average dwelling unit distances within extended kinship groups tend to be smaller than average dwelling unit distances between kinship groups, at least in a substantial majority of the villages.

What about the extent to which spatial distances between dwelling units differ in kinship groups which contain relinking compared to those without relinking? We tackle this issue directly in figures 6, 7 and 8, which give village-specific detail on the distances between dwelling units in different extended kin groups and within extended kin groups that relink and those that do not. These illustrations are for villages A, B and C discussed above. To simplify the upcoming discussion, we refer to dyads within kinship groups which do not relink simply as within-group dyads and to those within kinship groups that do relink as relinking dyads (whether or not the particular dyad of interest is the source of the relinking). Rather than a single summary for an entire village, Figures 6–8 show the entire distribution of dyadic dwelling unit distances as a function of kin-group status (between, within-group and relinking). They use kernel density estimation and smoothing procedures to calculate how the probability distribution (y-axis) varies as a function of dwellling unit distance (x-axis); for readers unfamiliar with kernel density estimation procedures Duang (2001) gives an overview.

Figure 6.

Kernel density plots of the distances between dwelling units by whether the dyad members are in the same kinship group, are in a relinking kinship group or are in different kinship groups in village A.

Figure 7.

Kernel density plots of the distances between dwelling units by whether the dyad members are in the same kinship group, are in a relinking kinship group or are in different kinship groups in village B.

Figure 8.

Kernel density plots of the distances between dwelling units by whether the dyad members are in the same kinship group, are in a relinking kinship group or are in different kinship groups in village C.

Figure 6 focuses on village A, a village where we observed no relinking in extended kinship groups. In this village, there are two important factors to notice about the relationship between a dyad's kinship status and the distance between its constituents' dwelling units. First, few, if any, between-group dyads are observed to be co-resident while a substantial fraction of within-group dyads are seen living together. This can be seen at the left of the x-axis, for distance equal to 0. Yet, while those that co-reside are primarily kin, co-residence is not the modal dwelling unit distance between members of within-group dyads. The second important feature to notice about village A can be seen in the middle range of distances (i.e., between about 1 and roughly 450 meters). A larger proportion of the between-group dyads live in those distances vis-à-vis the within-group dyads, a large number of whom tend to live around 500 meters apart. It is only at the farthest distances (i.e., beyond 1,000 meters) that the share of between-group dyads exceeds the share of within-group dyads.

Figure 7 shows village B whose settlement clusters (shown in Figure 4 above) can be clearly seen in the wavelike patterns in the graph. Some extended kinship groups in this village contain relinking. Interestingly, relinking dyads appear more similar to between-group dyads than they do to within-group dyads. While co-residence is the modal experience of within-group dyads in village B, relinking dyads, like between-group dyads, rarely tend to live in the same dwelling unit, if they do so at all. In comparison to what was seen in village A, in village B, a larger proportion of within-group dyads live nearer each other than the shares of between-group or relinking dyads. The relationship between settlement clusters and kinship is most evident in the second peak in Figure 7, which shows the shorter distances between dwelling units located in separate clusters when these dyads are in the same kinship group. It is an interesting result; though kin live in separate settlement areas within the village, they tend to live closer to each other than non kin. Again, at these longer distances, there appear to be no substantial differences between relinking dyads and between-group dyads.

Figure 8, which graphs these relationships in village C, echoes the trends seen in Figure 7. Co-residence explains much of the proximity of within-group dyads vis-à-vis between-group dyads. In village C as in village B, relinking dyads are more similar to between-group dyads than within-group ones.

Beyond basic differences in the patterns of spatial proximity of extended kin and non-kin across villages, we are also interested in relative differences within each village. To explore this, Figure 9 plots median between-group differences expressed as a proportion of median within-group distances,

| (2) |

, with uij (distance between individuals) and wij (same extended kinship group) defined as above, arranged by each village’s rank on raw within-group difference. Average distances in this figure were calculated excluding co-resident kin, but the pattern is the same as when distances are calculated including co-resident kin (not shown). In Figure 9, those villages with the smallest within-group average distances are found at the left of the x-axis, while those with the largest within-group average distances are at the right. It is clear that, with a handful of exceptions, distances between kin groups and in kin groups that have relinking are longer than distances within non relinking kin groups.

Figure 9.

Comparisons of kin group distances for non co-resident individuals proportional to distances within extended kin groups.

These analyses comparing the spatial distributions of extended kin and non-kin show the tendency for related individuals to reside closer in space than unrelated individuals. They also show that dyads in relinking kinship groups are more similar to dyads between kinship groups than they are to dyads within non-relinking groups, which is surprising if we expect endogamous kin groups to be more cohesive and that this cohesion translates into spatial proximity. However, these analyses have not yet examined whether or how closeness of kin tie matters for distance between dwelling units, a point we turn to in the next section.

Individual-oriented

Here, we analyze whether, and how, distance between dwelling units varies by degree of kinship relating members of a dyad. Table 3 aggregates the information across all 51 villages. Its two panels show the distribution of dyads across kin degree and categories of distance between dwelling units in terms of raw numbers and column percentages. The raw numbers show that most within-village dyads are not closely related. This may surprise those who have romantic views about kinship within village contexts but corresponds to what has been found in earlier work (Entwisle et al. 2007). Indeed, in the context of kinship relations in a society that shuns inbreeding11, it would be shocking if these were extremely dense networks. In addition, missing data on lower-order kin ties will appear as high-order ties or even no tie at all.

Table 3.

Distribution of person-to-person dyads within villages according to kin degree and dwelling unit distances

| Raw numbers | |||||

| 1 Deg. | 2 Deg. | 3 Deg. | 4 Deg. | 5+ Deg. | |

| Same DU | 46,217 | 19,293 | 2,475 | 432 | 2,555 |

| 1–49 M | 1,358 | 3,831 | 5,508 | 6,533 | 274,730 |

| 50–99 M | 1,136 | 4,093 | 7,148 | 9,286 | 647,696 |

| 100–49 M | 3,448 | 11,453 | 18,754 | 24,823 | 2,614,485 |

| 250–499 M | 3,366 | 11,351 | 18,681 | 24,310 | 3,437,805 |

| 500–999 M | 2,508 | 8,589 | 14,304 | 18,956 | 2,993,023 |

| 1000–M | 1,690 | 5,848 | 10,258 | 13,657 | 2,453,422 |

| Column Percentages | |||||

| 1 Deg. | 2 Deg. | 3 Deg. | 4 Deg. | 5+ Deg. | |

| Same DU | 77% | 30% | 3% | 0% | 0% |

| 1–50 M | 2% | 6% | 7% | 7% | 2% |

| 50–99 M | 2% | 6% | 9% | 9% | 5% |

| 100–249 M | 6% | 18% | 24% | 25% | 21% |

| 250–499 M | 6% | 18% | 24% | 25% | 28% |

| 500–999 M | 4% | 13% | 19% | 19% | 24% |

| 1000+ M | 3% | 9% | 13% | 14% | 20% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Note: Totals may not add up to 100% because of rounding. DU: dwelling unit.

Column percentages in Table 3 show that the likelihood of co-residence declines dramatically by kin degree in these villages: 77% of first-degree dyads co-reside, compared to 30% of second-degree dyads, and 3% of third-degree dyads. Almost none of the fourth and fifth-degree dyads co-reside. Correspondingly, the likelihood of living in dwelling units separated by relatively large distances (in the village setting) increases with kin degree. Only 3% of first-degree dyads live at distances of 1,000 meters or more, compared to 9% of second-degree ties, 13% of third-degree ties, 14% of fourth-degree ties, and 20% of all other dyads. This pattern holds for all dwelling unit distance categories greater than 250 meters. At intermediate distances (1 to 249 meters), percentages increase, then decrease at higher distances. For example, the percent of dyads separated by distances of 100–249 meters increases from 6% among first-degree dyads to 18% among second-degree dyads, and then to 24% and 25% among third- and fourth-degree dyads, but declines to 21% among fifth-degree and other dyads. We would expect these general patterns as preferences for residential proximity work themselves out over time in an area where fertility had exceeded replacement, available land for building new homes is constrained and there is no functioning real estate market - features which necessitate that more temporally removed descendants of the original settlers will live further from them.

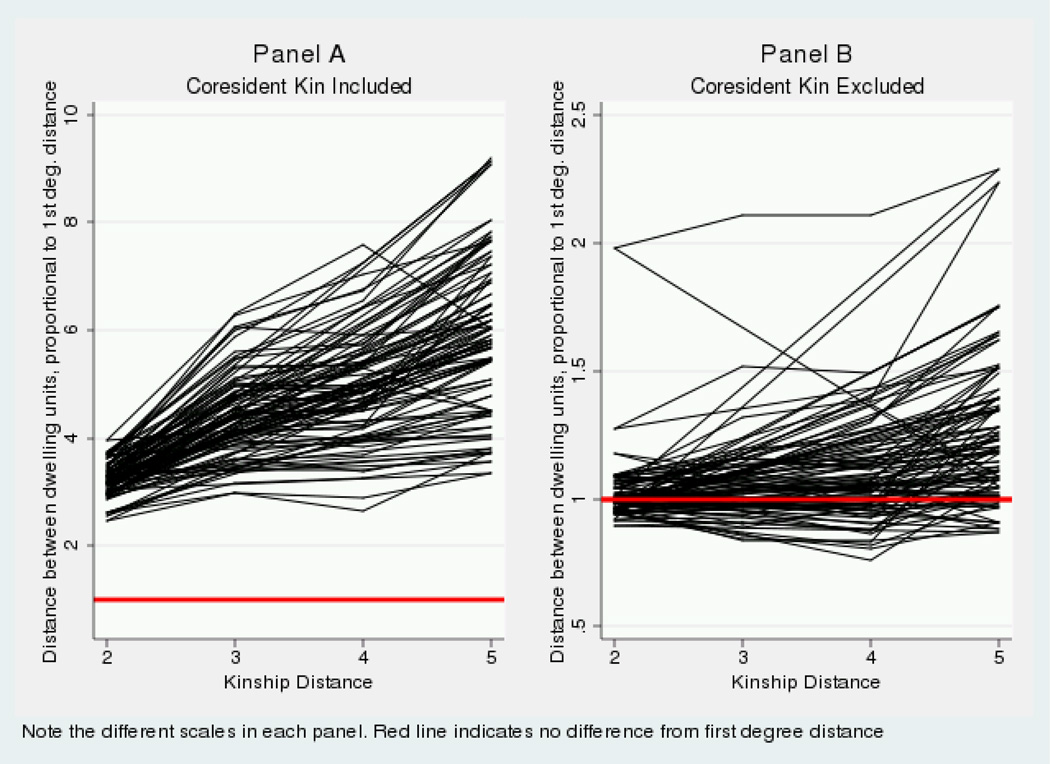

Figure 10 paints a similar picture. Its left panel presents the box plots of the distributions (across the 51 villages in our study) of mean distances between dwelling units for dyads of each kin degree. The median of the means (shown as the white line in the middle of each box plot) is 87.7 meters for first-degree dyads, 278.1 meters for second-degree dyads, 388.8 meters for third-degree dyads, 409.2 meters for fourth-degree dyads, and 508.5 meters for fifth-degree and other dyads. A positive relationship between kin degree and distance is clear in this sequence. We conducted matrix permutation tests on the relationship between kinship degree and distance in each of the 51 villages and confirmed that the associations were unlikely due to chance (not shown). Some of the differences in median dwelling unit distance are fairly large, especially those involving lower degree kin ties. The lower quartile for second-degree dyads (191.7 m.) is higher than the upper quartile for the first-degree dyads (132.0m.). The lower quartiles for fourth-, and fifth-degree and other ties (297.9m., and 335.2m) are higher than the median for second-degree dyads (278.1m), while the lower quartile of third-degree ties is close (270.7). This indicates differentiation in residential proximity among more closely related kin, less so among less closely related kin.

Figure 10.

Box plots of within-village mean distances between dwelling units, by kinship relatedness.

How much of the observed pattern is due to co-residence of closely related kin? Putting it another way, does the pattern hold among kin who do not live together? The right panel of Figure 10 presents box plots for mean distances between dwelling units for dyads of each kin degree excluding those living in the same dwelling unit. The pattern is much weaker than the one seen in the left panel. The medians are basically flat across kin degrees (390.2m., 400.1m., 403.0m., 412.7m., and 508.6m. for each kin degree, respectively). In no instance does the median for any degree of kinship fall outside the interquartile range of any other. There is a pattern of increase in the top parts of the distributions, however, especially among more distally related kin.

Given the social processes posited to underlie the expected pattern of spatial arrangements, and the environmental and other constraints on its expression, it is important to examine distances between dwelling units in the same village as well as comparing averages for different villages. Above, in arguing that the hypothesized relationship may still hold even when co-resident kin are not included, we posited that some villages may show the pattern of less closely related individuals living increasingly farther from each other, while others may not. Figure 11 explores this question. Its left panel shows the median distance of dyads for each kin degree in relation to distances between first-degree ties for each of the 51 villages in the data set. The x-axis orders kinship degree from closely related (first degree ties) to less closely related (fifth- or higher-degree ties and unrelated individuals), and the y-axis shows the mean dwelling unit distances proportional to the distance between first degree ties. Each village has its own line, which allows us to trace the mean distance in each village through the different degrees of kin relatedness; as above, the left panel shows all within-village dyads while the right panel shows only those not co-residing.

Figure 11.

Within-village relationships between dwelling unit proximity and kinship distance

Reading from the left panel, it can be seen that within most (but not all) villages, there is a clear positive relationship between the kin degree of the dyad and median distance. However, when we omit the co-resident dyads as in the right panel, the pattern is much less pronounced, and indeed, does not appear to hold at all for many villages. That said, there is some evidence to support a positive relationship between kin degree and distance, even when co-resident dyads are excluded. By showing how the relationships look within villages rather than when villages are combined, such a pattern is evident in some villages but not others.

As noted earlier, each kin degree combines a heterogeneous assortment of kin relationships of varying intensity. Take, for example, first degree kin. These are parent-child ties and spousal ties. Excluding co-resident dyads eliminates almost all of the spousal ties from consideration. There are a few spouses living separately in the villages, but not many. Thus, when comparing non co-resident first and second degree ties, we are really comparing dyads containing parents and their adult children living separately (first-degree) with dyads of adult siblings, grandparents and grandchildren, and adult children and their parents-in-law (second-degree). Given that the observed patterns of social and spatial proximity are based on residential preferences expressed over previous generations, it is not clear that these categories are very different. We might expect to see more when comparing second-degree ties with higher-degree ties.

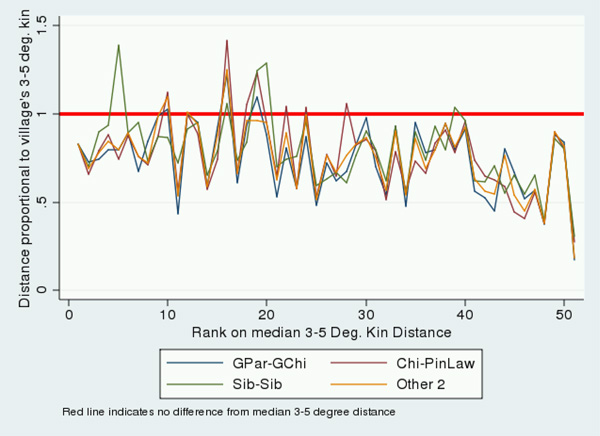

Figure 12 breaks second-degree ties into its constituents and compares them to third- and higher-degree ties. It plots median distances for non co-resident sibling, grandparent-grandchild, child-parent-in-law, and all other second-degree ties, ordering villages according to median distance on third- and higher-degree ties. In the vast majority of instances, medians for specific second-degree ties are less than the median for higher-degree ties in each village (values less than one). There is little regularity in the exceptions. Sometimes, non co-resident siblings live farther away from each other than those less closely related. Sometimes, it is the non co-resident children and parents-in-law who do. Distances between grandparents and grandchildren are least likely to deviate from expectations, but there are a couple of exceptions even with this group. Some of the irregularity is likely due to “float and bounce,” as the numbers get pretty small in some villages. The contrasts are stronger when non co-resident third- and higher-degree ties are grouped (as shown) than when comparisons just involve, for example, non co-resident second-and third-degree ties.

Figure 12.

Median distances for non co-resident sibling, grandparent-grandchild, child-parent-in-law, and all other second-degree ties proportional to distances for 3rd+ degree ties and unrelated individuals, excluding co-resident dyads

Discussion

Our motivating research questions concern the association between kinship and residential proximity. This general question requires refinement to consider the various levels and ways we can operationalize both kinship networks and residential proximity. Our analyses are also affected by characteristics of our study site and the data available in the Nang Rong surveys. In this section we consider these issues and how they impact the scope of our conclusions. In particular, we highlight the presence of consistent results on the association between kinship and spatial proximity, while recognizing variability across villages; the impact of boundary definitions, both for networks and spatial regions, and the potential problems of missing data; strengths and weaknesses of the system- and individual-level approaches to kinship networks; and specific features of our study site that impact conclusions about kinship and residential proximity.

Variation across villages

We began our analyses with a simple question: are average dwelling unit distances within extended kin groups shorter than average dwelling unit distances between extended kin groups? Our results indicate that they are, to a greater extent than would be expected by chance in most cases. However, in almost a quarter of cases we did not find this relationship. This underscores a strength of our data, the ability to see broad patterns that are regular but not deterministic. It also offers a cautionary tale about generalizability. Many social network studies rely on detailed data collected about a small number of people in one location. Had we followed this route and focused on only one village, we may have found the pattern. Yet a few kilometers away in a place with a similar cultural, historical and demographic heritage, the pattern would not have been found. Similar ideas about the diversity of kinship forms in Thailand have been reported in Foster (1982) and earlier research on Nang Rong has also shown variation from one village to the next in the patterning of social ties (Entwisle et al. 2007). Yet this strength also highlights a constraint on the generality of our conclusions; although the general association between spatial proximity and social relations will hold across a broad range of settings and social relations (Butts 2002, 2003; and papers in this special issue), we make no claims that the particular patterns found in Nang Rong will be found elsewhere.

Social boundaries and spatial scale

Another, less obvious constraint on the generality of our conclusions is that we limited our analyses to within-village dyads and excluded links between villages and to migrants living elsewhere. To some extent, this decision was not a choice; since we collected kinship data as spouse and parent-child ties (supplemented with sibling information in many cases) and not complete genealogies, we lack data on kinship between individuals in separate villages. We also do not have complete data on the dwelling unit locations of migrants. It is worth considering how such boundary setting may impact the observed relationship between kinship association and spatial proximity.

Limiting our analyses to within-village links raises three related issues. The first is the possibility that, by excluding individuals from our analysis, we are also excluding their direct links to alters, which is a problem that compounds the further from ego the extended kinship tie is calculated (Verdery et al. 2009). While not all direct links were captured and this could limit our analyses of higher-order kin, excluding ties to those outside the village is not, per se, the source of this because dyads which contained out-of-village individuals were excluded only after the kinship distances between all dyads (including those who had left the village) were calculated. Thus, if two people are linked indirectly via a tie through someone not in the village, they remain connected (at a kinship degree of 2+) in our analyses, provided we observe the direct kinship links to that person. Indirect kinship ties through the dead provide a comparable example, so long as the dead person was in our sample at some point.

The second, more profound issue to consider when thinking about the impacts of looking only at ties within villages relates directly to the theme of this special issue: to what extent does the shared data in both sets reflect the appropriate network boundary and spatial scale? In the simultaneous analysis of social and spatial networks, there is likely to be a trade-off between the viability of the social network boundary and the spatial scale that is being analyzed. Negotiating the two is tricky. Here, from the social side where we are interested in kinship, the within-village boundary seems arbitrary since kin relations transcend space. Yet the within-village scale makes sense from the spatial side because we are interested in dwelling unit distances as a possible reflection of daily activities and prior work (e.g., Entwisle et al. 2006) as well as our knowledge of the study area indicates that quotidian interactions between villages are less common than within them. For the questions we address in this paper, the within-village boundary is appropriate, but for other questions (e.g., those related to the development of relinking kin sets), it is likely a problematic constraint imposed by the data source.

A third issue that arises from the limitation of our analysis to within-village ties is the possibility that those who remain in the village are a selected group, perhaps more prone to traditional habitation structures. We find some evidence that this is the case in our estimates of gender differentials of endogamy and what they say about post-nuptial residence patterns (see note 12 below); the “traditional.” post-nuptial residence pattern of Thailand where husbands move to the village of their wives is stronger in the endogamous group than in other reports (e.g., Foster 1985) or among the non-endogamous. However, it is difficult to imagine how such selectivity would invalidate our conclusions, which generally accord with the theoretical models we have discussed. Further, the pressures of migration operate on many rural areas worldwide, and, to the extent that those inclined toward more traditional living-arrangements are left behind, the limitation to within-village dyads may make our descriptive results more generalizable and relatable to other areas

Approaches to the analysis of kinship

Our analysis used both system- and individual-level approaches to kinships networks, and insights were gained from each. With respect to the system level analysis of extended kinship, although we found that pairs of individuals in extended kin networks tended to live closer to each other than did unrelated individuals, members of extended kin groups with marital relinking did not. This unexpected finding suggests that, in the Thai context, marital relinking is not an indicator of greater cohesion, at least as expressed in residential proximity. It also reminds us that marital relinking might not be a salient characteristic of some kinship systems12. In addition, in our sample, kinship groups with relinking tend to be larger in size since relinking will only occur if prohibitions on incest do not prevent a marriage. When a kinship group is larger, any pair of members is likely to be less related to each other than they would be in a smaller group, ceteris paribus. Further, given that the relinking of an extended kinship group is conditioned by the choice of two individuals to marry (Thailand has not historically had arranged marriages), it may be that groups only relink when members are spatially dispersed enough for the couple in question to not perceive their kinship; anthropologists working in Thailand have suggested that marriages between individuals perceived to be related are discouraged (Foster 1975: 36; 1982: 447).

In addition to addressing questions about kinship and dwelling unit distance in a global sense, where the social network focus is on extended kinship groups, we also approached these topics from an individual-centered perspective, where the focus is on the type (and closeness) of relations between members of a dyad. The individual perspective allows for new and important questions to be asked: Is the degree of kinship relation between two individuals positively associated with the propinquity of their dwelling units? Is this relationship driven by the tendency of close kin to live together, or do close kin who live apart also tend to live closer to each other than unconnected individuals? Our individual-oriented approach allowed us to probe in detail how different degrees of kinship were related to dwelling unit proximity, even though we lack information on complete genealogies. Knowledge of complete genealogies and links to and between dead individuals are required to exhaustively enumerate extended kin groups, but information of this sort is simply not available in large social surveys of tens of thousands of respondents.

Specifics of our study area

Readers should bear in mind the historical conditions of our study area as they pertain to our results. It is possible that some of the variation between villages may be related to the unique history and circumstances of each one.

Looking at villages individually, and examining non co-resident dyads only, we found a positive correlation between kin degree and residential distance for some villages but not others. That most Nang Rong villages were settled relatively recently means that we can potentially “see” spatial patterning related to generational succession which we expect explains this finding. In many cases, the original settlers arrived a little more than a half century ago. Villages now contain the children, grandchildren and perhaps some great-grandchildren of these settlers as well as others who may have moved into the village in the meantime, especially through marriage. Given cultural preferences within constraints imposed by local topography and flooding associated with the seasonal monsoon, village settlement will radiate outwards. Each generation remaining in the village attempts to construct dwelling units on high land close to their parents or in-laws. The availability of such land will depend on previous settlement patterns. Over time, the ability to satisfy preferences regarding proximity might decrease, and with the passage of enough time, it might not be possible to detect an association between kin degree and spatial proximity.

Indeed, we might have seen a stronger pattern had we conducted our analysis closer to the time of initial village settlement, assuming such data were available (which they are not). On the other hand, it is worth noting that a market for buying and selling dwelling units and land has not yet developed in Nang Rong. Should such a market emerge, coupled with a preference for living close to relatives, it is possible that we will see a stronger pattern of association between closeness of kin ties and distance between dwelling units. We expect that some aspects of this expression of residential selection and kinship will be general across settings and historical periods, though specific details will vary (for example, related to housing stock, real estate markets, and aspects of the built environment).

Conclusions

Previous research on the relationship between social networks and geographic space has given little attention to the spatial proximity of close kin living in different households, or to the geographical patterning of more distantly related kin at all, largely as a result of data limitations. Prior studies provide limited understanding of the residential choices made by individuals and consequently have painted an incomplete picture of kinship integration in communities. For instance, the literature on family organization has long been criticized for failing to account for the possibility that close kin live nearby (cf. Ruggles 1990). Looking beyond household co-residence and beyond the kinship ties of closely related individuals has the potential to offer valuable insights into the structure of the family and the role that extended kinship might play in reinforcing proximity effects on interaction, as well as shedding light on the coincidence of social and spatial distance more generally.

Moreover, unlike social ties such as friendship, conversations, or provision of routine assistance, which have been shown to depend on spatial proximity for their activation, kinship likely is associated with space thorough residential decisions that individuals make and how proximity to kin factors into these decisions. Such an insight may add new mechanisms to models of residential segregation (e.g., Bruch and Mare 2006; Park, Burgess and Mckenzie 1925). It is unlikely a coincidence that the early concern with spatial segregation in the U.S. arose in the early 1900s in Chicago, which, like Nang Rong during the period under study, had been only recently settled after receiving a large amount of in-migration about fifty years before (Park, Burgess and McKenzie 1925). Considering that people who are related tend to live near to one another when possible, it may be that much of this early concern with residential segregation of migrant groups was ignoring the influence of time and available housing stock in patterns of spatial assimilation. As migrants (including migrants from other parts of the country) move into new areas they tend to live with one another (Korinek, Entwisle and Jamapklay 2005), then near one another, until finally there is no relationship between whether people are kin and where they live.

The availability of spatially referenced complete networks replicated over 51 communities for Nang Rong, Thailand has enabled us to address long theorized but understudied questions about kinship and residential proximity. We found a positive correlation between the closeness of the kin tie as measured by kin degree and the proximity of dwelling units for all dyads combined. This association is largely due to the fact that close kin are more likely than distant kin to live in the same dwelling unit. Co-residence of close kin is an extreme form of the association between social and spatial proximity. When we examine dyads that are not coresident, patterns are much weaker. They are weak but evident in some villages, and non-existent in others. Partly, this is due to the fact that first- and second-degree ties that are not co-resident involve adult children and their parents and parents-in law. There is more of a pattern contrasting between second- and third-degree with higher degree ties. In addition, missing data might be a factor. As discussed above, the impacts of missing data increase with kin degree and may weaken patterns of association with spatial proximity among third- and higher degree kin ties Whatever the explanation, it is clear that co-residence is responsible for much of the association between kin and residential proximity in the Nang Rong villages.

Yet, there is suggestive evidence that co-residence does not explain all of this association. Villages are small and all family members are, in fact, nearby. Indeed, limiting our analyses to within-village dyads is a strict test; at larger scales of aggregation, such as all of Thailand, there would almost undoubtedly be a relationship between kinship and spatial proximity of non-coresident individuals. The geographic and genealogical bounds we placed on our analysis are analytically useful but must be remembered when interpreting the results. While we have considered the kinship connections of those who co-reside and those who live in the same village, there are other important layers: connections to and among those who live apart, especially migrants. The spatial distances between those who live in the same village, kin or not, are certainly much less than the distances between village residents and emigrants (Entwisle et al. 2010), and, though it is known that migrants from the same Nang Rong villages tend to cluster together in their destinations (Shao et al. 2008), little is known about the relationship between such clustering and kinship ties. Such questions are interesting and present important directions for future research. A full-fledged model of network and spatial ties will invariably have to account for such multi-level layering of relations.

In conclusion, this analysis shows an important application of the simultaneous integration of social network and spatial analytic methods, and the potential for their combination to shed light on the role of the family in social life. It is clear that associations between social and spatial proximity depend on time and place. The Nang Rong villages are relatively small, in terms of both population and geographic area. Dwelling units are clustered, often in shapes that follow the contour lines of local topography. Dwelling unit distances of a kilometer or more put dyads into the top quartile of all person-to-person dyads in the village. Rural villages elsewhere may be configured quite differently, and this is certainly the case for urban communities. That said, social interaction is influenced by spatial proximity in many settings and this is probably true in Nang Rong as well. Spatial proximity of close kin likely reinforces the impact of kin networks on a variety of outcomes such as migration behavior (Entwisle et al. 2010). The differences we observe are relatively small, perhaps 100 or 200 meters, but as the prior literature shows (e.g., Butts 2002, 2003; Mouw and Entwisle 2006), small differences can be important.

Research Highlights.

* Please provide Research Highlights for your paper. Research highlights consist of a short collection of bullet points that convey the core findings of the article. Correct format for Research Highlights are 3–5 bullet points, no more than 85 characters per bullet point. See http://www.elsevier.com/researchhighlights for examples. Thanks you!

Preferred proximity to kin may determine people's residential locations.

Kin live nearer to each other than non-kin as do close kin than less close kin.

Co-residence accounts for much of the kinship-proximity relationship.

Social networks affect the spatial distribution of individuals.

The effect of network ties on residential proximity is ripe for additional research.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (R21 HD051776), the National Institute for Environmental Health Science (R21 ES016729), and the National Science Foundation (HSD 0728822). We would also like to thank Rick O’Hara and Philip McDaniel for their programming expertise and Bridget Riordan for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

We calculate kinship networks on all of the more than 50,000 individuals ever enumerated in the Nang Rong surveys. Our final sample for the analysis of the relationship between kin ties and residential proximity within villages is 24,536. We restrict the sample to individuals currently living in the study villages at the time of the 2000 wave of data collection (e.g., non-migrants) who were matched to their respective dwelling units

Note that there were 12,281 migrants living outside of the study villages at this time.

The metric system is used in this paper. For readers used to thinking in feet and miles, note that 1 meter isapproximately 3.3 feet, and 1 kilometer (1,000 meters) is approximately 0.62 miles.

We use 60 as an elderly cutoff age for calculating the dependency ratios presented in Table 1 rather than the more common 65 to reflect the agricultural setting of the area, where work – primarily rice-harvesting – is extremely labor intensive.

Rai is a Thai unit of areal measurement equivalent to 0.16 hectares or 0.39 acres.

In constructing these kin networks we include those residing in the 51 Nang Rong villages in 2000 as well as those who were present in earlier waves of data collection (1984 and 1994) but had migrated from the village or died prior to 2000. However, the substantive analyses focus only on those residing in the 51 villages in 2000.

Note that the numbers reported reflect the component size distribution found amongst all respondents in the NangRong data including those who died between the 1984 and 2000 survey waves, the analyses presented below arebased on a subset of these individuals who are living, resident in the village, and for whom we have GIS locations oftheir dwelling units.