Abstract

Intranasal oxytocin (IN-OT) modulates social perception and cognition in humans and could be an effective pharmacotherapy for treating social impairments associated with neuropsychiatric disorders, like autism. However, it is unknown how IN-OT modulates social cognition, its effect after repeated use, or its impact on the developing brain. Animal models are urgently needed. This study examined the effect of IN-OT on social perception in monkeys using tasks that reveal some of the social impairments seen in autism. Six rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta, 4 males) received a 48 IU dose of OT or saline placebo using a pediatric nebulizer. An hour later, they performed a computerized task (the dot-probe task) to measure their attentional bias to social, emotional, and nonsocial images. Results showed that IN-OT significantly reduced monkeys’ attention to negative facial expressions, but not neutral faces or clip art images and, additionally, showed a trend to enhance monkeys’ attention to direct versus averted gaze faces. This study is the first to demonstrate an effect of IN-OT on social perception in monkeys, IN-OT selectively reduced monkey’s attention to negative facial expressions, but not neutral social or nonsocial images. These findings complement several reports in humans showing that IN-OT reduces the aversive quality of social images suggesting that, like humans, monkey social perception is mediated by the oxytocinergic system. Importantly, these results in monkeys suggest that IN-OT does not dampen the emotional salience of social stimuli, but rather acts to affect the evaluation of emotional images during the early stages of information processing.

Keywords: Oxytocin, attention, gaze, facial expression, social cognition, autism

Because of its modulatory effects on social and emotional behavior in mammals, oxytocin (OT) has emerged as a leading potential pharmacotherapy for the treatment of people with social impairments, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Modi & Young, 2012). This is especially exciting because one of the most common symptoms of ASD is lack of social interest and any drug that may increase the salience of social cues, social reward, or social motivation could significantly improve the success of existing treatments. Single dose studies in adults with ASD have shown that OT reduces repetitive behaviors (Hollander et al., 2003), increases social interaction and attention to the eyes in faces (Andari et al., 2010), and improves the ability to read facial emotions (Guastella et al., 2010). While these studies are extremely encouraging, it remains unclear how, in terms of biological mechanism, or where, in terms of neural specificity, OT is exerting these beneficial effects (Churchland & Winkeman, 2012). Moreover, important preclinical testing related to therapeutic dose, effects after repeated use, or impact on the developing brain have yet to be conducted. Animal models are critically needed and the most effective model should be one in which OT affects similar behaviors and neurobiological processes as those impacted in humans and, ideally, these behaviors should be ones that are adversely affected in humans with social impairments. The present study provides the first evidence that intranasal (IN) OT alters the evaluation of social stimuli in rhesus monkeys, similar to humans.

Oxytocin is a neurohypophyseal peptide that acts as a neuromodulator in the brain where it plays a key role in regulating social and emotional behaviors (Neumann, 2008). Human studies have reported a wide range of effects of IN-OT on socio-emotional behavior and social cognition, including increased salience of the eyes in faces, more accurate emotion recognition (Domes et al., 2007a; Fischer-Shofty et al., 2010; Gamer et al., 2010; Guastella et al., 2008; Savaskan et al., 2008), improved memory for face identity (Rimmele et al., 2009; Savaskan et al., 2008), and enhanced socially reinforced learning (Hurlemann et al., 2010). Several studies have shown an effect of IN-OT on more complex socio-cognitive behaviors, including trust (Baumgartner et al., 2008; Kosfeld et al., 2005; Theodoridou et al., 2009) and empathy (Bartz et al., 2011; Hurleman et al., 2010; but see Singer et al., 2008). The wide range of behavioral effects revealed by these studies suggests that IN-OT may be impacting multiple neural systems including those involved in reward, memory, basic perception, and information processing. Indeed, several possible (not mutually exclusive) mechanisms have been proposed for how IN-OT may be exerting its effects including a) reducing social anxiety- leading to increased social interactions and trust, b) enhancing social motivation- leading to stronger social bonds and higher rates of social affiliation, or c) increasing the salience of social cues- leading to more accurate social information processing and possibly stronger memory for social information (Bartz et al., 2011).

Several studies have specifically tested this latter mechanism, referred to as the social salience hypothesis, by studying the effect of OT on the perception of social stimuli. These studies capitalize on the well-known ‘negativity bias’ shown by humans in which attention is automatically and unconsciously drawn to negative, threatening, or aversive stimuli during the early stages of information processing (Ito et al., 1998; Ohman et al., 2001). Ellenbogen and colleagues (2012) used a spatial cueing task to show that IN-OT reduced subjects’ attention to sad compared to angry faces and increased their speed to disengage from angry faces. These findings are supported by numerous fMRI studies demonstrating that IN-OT reduces amygdala activation in response to emotional faces (Baumgartner et al., 2008; Domes et al., 2007b; Kirsch et al., 2005; Petrovic et al., 2008). Several studies have now shown that IN-OT does not affect the perception of all social stimuli in the same way but, rather, selectively affects the perception of negative emotional stimuli. Norman and colleagues (2010), for example, showed that IN-OT significantly reduced ratings of arousal for negative compared to positive social images, and Striepens and colleagues (2012) found that IN-OT significantly potentiated an acoustic startle response to negative emotional stimuli without affecting subjects’ ratings of stimulus valence or arousal. These subjects also showed enhanced memory for the proportion of negative compared to neutral pictures subsequently remembered. This study is important as it counters a common concern that IN-OT is acting as a general anxiolytic, dampening responses to all emotional stimuli. Instead, these studies support the role of IN-OT in selectively enhancing the salience of aversive social stimuli. Interestingly, Striepens and colleagues (2012) also performed fMRI on subjects as they viewed the emotional stimuli used during the startle testing and confirmed the well-replicated finding of reduced amygdala activity in response to the negative images, but they also reported enhanced connectivity between the amygdala, insula, and inferior frontal gyrus, which may help to explain the memory modulating effects of OT that they reported. These results suggest that IN-OT may be potent in not only affecting the early stages of information processing, e.g., the initial evaluation of social images, but the more complex socio-cognitive effects reported in humans, like increased trust and empathy. These results may even help explain the context- and person-dependent effects of OT, such as the avoidance of attractive females by monogamous but not single men (Scheele et al., 2012), and the increase of ingroup favoritism and outgroup derogation (De Dreu et al., 2010); these effects are presumed to depend on the subsequent, additional processing of emotional stimuli by downstream neural systems (Bartz et al., 2011; Ellenbogen et al., 2012; Panksepp, 2009).

Before OT can be developed as an effective pharmacotherapy for treating people with social impairments, preclinical screening is needed. Monkeys represent an ideal species for this purpose because they share many of the same socio-cognitive behaviors with humans, such as recognition of faces and facial expressions, however, only a handful of studies have examined the effects of OT on social behavior in nonhuman primates. Some have reported a positive effect of introcerebroventricular (ICV) administration of OT on dominance behavior and grooming in squirrel monkeys (Winslow & Insel, 1991). Others have found effects of ICV-OT on males’ tolerance towards food begging from infants in a biparental species of marmoset (Saito et al., 2011), and IN-OT has been shown to increase social contact in pair-bonded marmosets (Smith et al., 2010). Finally, IN-OT has been shown to increase vicarious reinforcement in rhesus monkeys (Chang et al., 2012). This study also confirmed the efficacy of intranasal OT in crossing the blood brain barrier in rhesus monkeys (Chang et al., 2012; see Born et al., 2002). No studies to date have examined the effect of IN-OT on social perception in monkeys. Therefore, it is the goal of this study to examine the effect of IN-OT on attention to faces and facial expressions in rhesus monkeys to determine whether the behavioral and neurobiological systems underlying social perception and cognition in monkeys are also modulated by oxytocin. We hypothesized that IN-OT would reduce monkeys’ attention to negative facial expressions, but not neutral faces or nonsocial stimuli, consistent with reduced amygdala activation (Domes et al., 2007b; Kirsch et al., 2005). We also predicted that IN-OT would increase attention to direct compared to averted gaze faces. These results will be important for the development of a preclinical model for evaluating the neurobehavioral effects of IN-OT on social cognition and emotional behavior.

Methods

Subjects

Six rhesus monkeys were used in these studies. All were mother-reared in large social groups for the first three years of life. Four (2 males and 2 females, ~12 yrs) had been used in numerous computerized studies of face processing (see Parr, 2011), while the remaining 2 males (~3 yrs) were experimentally naïve. All subjects were housed in same-sex pairs in the same colony room and received food and water ad libitum. None of the subjects had ever performed the dot-probe task or received any pharmacological manipulations prior to these studies.

Testing Procedure & Stimuli

Subjects were tested in their home cage using a dot-probe task presented on a touchscreen computer. Each trial was initiated when the subject touched a central fixation cross on the screen. This was followed immediately by a brief (500 ms) presentation of two images on either side of the monitor. One image was emotionally salient, e.g., a facial expression, while the other was neutral, e.g., neutral face or nonsocial image. After this, a target appeared in a location that was congruent with one of the images. Reaction time to contact the target was the dependent variable (MacLeod et al., 1986). After touching the target, the subject received a small food reward and a 5 s ITI before the fixation cross appeared to initiate the next trial. In the dot-probe task (see Figure 1), response time is associated with image salience such that faster reaction times are expected in the emotionally congruent versus incongruent conditions (Bar-Haim et al., 2007; Koster et al., 2004; Mather & Carstensen, 2003).

Figure 1.

An example of the dot-probe task. From left to right, a) subjects must first contact a fixation cross located centrally on a touchscreen monitor. After this they are presented with two images for 500 ms (b), followed by a rectangular target that is congruent with the location of one of the two images. In panel c, the target is shown in a location congruent with the emotional expression. Reaction time to touch the target is the dependent variable.

Four categories of stimuli were presented, neutral faces, facial expressions, direct and averted gaze faces, and clip art images. These were combined into two tasks to minimize the number of trials to be presented in a testing session. Task 1 presented faces and facial expressions. The latter category combined two types of facial expressions, bared-teeth displays and open mouth threats. Task 2 presented the direct and averted gaze faces and clip art images. Figure 2 illustrates each category of image used in the two tasks. For each task, subjects received a single 100 trial session that balanced pseudorandomly the number of trials in each of the four possible configurations- congruent and incongruent trials for each of the two stimulus categories (Task 1, neutral faces and facial expressions and Task 2, gaze faces and clip art). It should be noted that the custom software used to present the images prioritized the full counterbalancing of congruent and incongruent trials (50 of each for the 100 trials shown), not the complete counterbalancing of congruency and stimulus category. The later procedure would have produced exactly 25 trials in each of the four configurations. Instead, the data produced consisted of approximately 25 in each configuration, but exactly 50 trials in each congruency condition. In Task 1, for example, approximately 25 trials showed neutral faces with the target congruent with the face, approximately 25 trials showed neutral faces with the target incongruent with the face (congruent with the scrambled face), approximately twenty-five trials showed facial expressions with the target congruent with the expression, and approximately 25 trials showed facial expressions in which the target was incongruent with the expression (congruent with the scrambled expression). The same procedures were applied to Task 2.

Figure 2.

An example of images from each stimulus category in the two tasks. Task 1 showed neutral faces and facial expressions of unfamiliar conspecifics paired with their scrambled equivalents. Two expressions were combined in this category, bared-teeth displays and open mouth threats. Task 2 presented two neutral faces of the same individual monkey with direct and averted gaze, or clip art images paired with their scrambled equivalents.

Ten unique examples of images from each stimulus category were available for presentation. These images were drawn randomly by the software. So within a 100 trial session subjects were not ensured to be presented with the exact same number of images, rather they were presented with an equivalent number of images from each category. As stated above, the software prioritized the congruency of trials, so each 100 trial session showed exactly 50 congruent and 50 incongruent trials. Of those 50 congruent trials, for example, 23 may have been expression trials and 27 may have been faces. The 23 expressions would have been drawn randomly from the 10 possible unique examples described above.

In the first task, the unfamiliar conspecific faces and facial expressions were presented along with their scrambled equivalent, e.g., face versus scrambled face or expression versus scrambled expression. Therefore, the two images in a trial contained the same visual information, but only one was veridical (see Figure 2). The neutral faces showed unfamiliar adult conspecific females. Five examples of two species-typical facial expressions were presented in the facial expression category, e.g, the bared-teeth display, an appeasing, dominance-related signal (de Waal & Luttrell, 1986; Waller et al., 2005), and the open mouth threat, an aggressive, threatening facial expression. These are commonly occurring expressions that communicate important socio-emotional information and monkeys readily discriminate between them (Parr & Heintz, 2009). The scrambling was performed using in Matlab using a script that divided each image into 10 × 10 pixel squares and then randomly reassigned the location of these squares within the image space.

In the second task, subjects were presented with 10 novel examples of unfamiliar neutral faces and clip art images. These were drawn randomly by the software as described above for trials in Task 1. In the face trials, the two images in the pair showed the same individual, but in one picture the face had direct gaze while in the other the gaze was averted. For the analyses (see below), the direct gaze faces were designated as the emotional image within the pair. For the clip art trials, each image was paired with its scrambled equivalent, as described above. Clip art images did not include faces or face-like patterns. Image size was standardized prior to presentation. Order of image presentation, side of target in congruent trials, and side of each image type in a pair was randomized within a testing session. All images were shown in color.

Oxytocin Administration Procedure

Prior to testing, subjects were administered either a 48IU1 dose of OT (Sigma #06379,1.71 µg/IU in a 2ml volume) or saline placebo (2ml) in aerosol form using a pediatric nebulizer (www.pari.com). This method has been proven effective in delivering OT to the central nervous system in rhesus monkeys (Chang et al., 2012; Modi et al., submitted). To train monkeys for this procedure, they were placed in a specially designed cage that contained a clear Plexiglas panel to which the nebulizer was attached (Figure 3). Also inserted into this panel was a small tube through which a slow stream (9 ml/min) of fluid reward (diluted yogurt) was delivered. This encouraged subjects to maintain their face in a position over the nebulizer and breathe through their nose. Subjects were required to sip on this tube for 4 cumulative minutes, within a 5 minute window, while aerosolized saline was delivered just below the nose of the subject through the nebulizer tube. Once subjects reached this criterion, the experimental testing began. Given the broad range of doses and administration routes used in previous animal and human studies, no attempt was made to correct the dose for subjects’ body weight.

Figure 3.

The procedure panel for administering IN-OT or IN-placebo to monkeys using a nebulizer. The nebulizer attaches to an opening in the panel that contains a juice delivery tube. Subjects were required to sip a slow rate of juice for 4 cumulative minutes while the aerosolized compound was delivered below the subject’s nose.

For each task, the order of treatment condition (placebo vs OT) was counterbalanced across subjects. Half of the subjects were first tested in Placebo condition while the other half received the OT condition. The order of treatment condition was reversed for task 2, so a subject that first received Placebo in Task 1 received OT in Task 2. Testing on each task/treatment condition was separated by a minimum of 7 days. If subjects did not achieve a cumulative 4 minutes of sipping during the dosing procedure for either treatment condition, the experiment was aborted and attempted the following week. Testing began 60 minutes after dosing, comparable to the peak uptake of OT in CSF (Chang et al., 2012; Modi et al., submitted). During this time, subjects rested in their home cage. After 60 minutes, a custom designed touchscreen panel was attached to the subject’s home cage to administer the task. Subjects remained separated from their social partners during testing and both monkeys in a pair were tested simultaneously. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University and were in compliance with regulations governing the ethical treatment of animals.

Data Analysis

The RT data (in seconds) were averaged for the congruent and incongruent trials for each subject and stimulus category and then converted to an ‘attentional bias’ score by subtracting the mean RT in the incongruent stimulus condition from the congruent stimulus condition. Thus, positive values indicated faster overall RT in the congruent stimulus condition (Ellenbogen et al., 2012; Mather & Carstensen, 2003). The task was programmed to time out and advance to the next trial if the subject did not respond within 5 s. Additionally, trials were excluded if a subject’s response time exceeded 1.5 s. Data were analyzed only if subjects completed 80% of the trials in a session2.

An initial analysis was performed to determine whether treatment condition affected overall RT by comparing the mean RT for contacting all targets in each task, regardless of the location/congruency of the stimulus, using a paired t-test (two-tailed). Second, a 2 × 4 repeated measures ANOVA was used to analyze the attentional bias scores using two levels of treatment condition (P vs OT) and 4-levels of image category (faces, expressions, gaze direction and clip art) as the within-subject factors. Follow-up analyses were performed where appropriate. Prior to running the ANOVAs, we analyzed whether the attentional bias scores violated a normal distribution using Shapiro-Wilks tests. This confirmed that the data from each stimulus category did not deviate from the normal distribution.

Results

In the initial analysis, paired t-tests confirmed that there were no significant differences in mean RT between treatment conditions for any stimulus category. Therefore, OT had no overall effect on response times. Table 1 shows the mean (+sem) RT data for responses to each stimulus type in each treatment condition.

Table 1.

Mean overall RT to contact the target in placebo and OT conditions for each stimulus type.

| Trial Type | Condition | Mean RT (+sem) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faces | Placebo | 0.482 (0.03) | 0.66 |

| Faces | Oxytocin | 0.489 (0.03) | |

| Expressions | Placebo | 0.500 (0.04) | 1.00 |

| Expressions | Oxytocin | 0.500 (0.04) | |

| Clip art | placebo | 0.476 (0.03) | 0.46 |

| Clip art | Oxytocin | 0.456 (0.03) | |

| Direct/averted gaze | Placebo | 0.469 (0.03) | 0.24 |

| Direct/averted gaze | Oxytocin | 0.450 (0.03) |

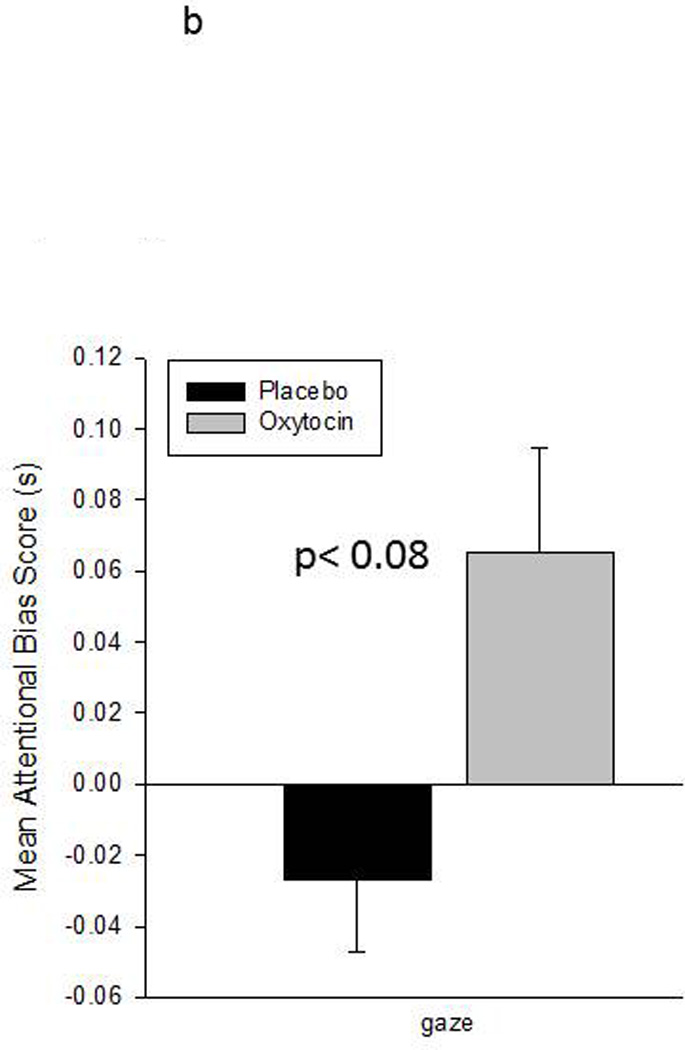

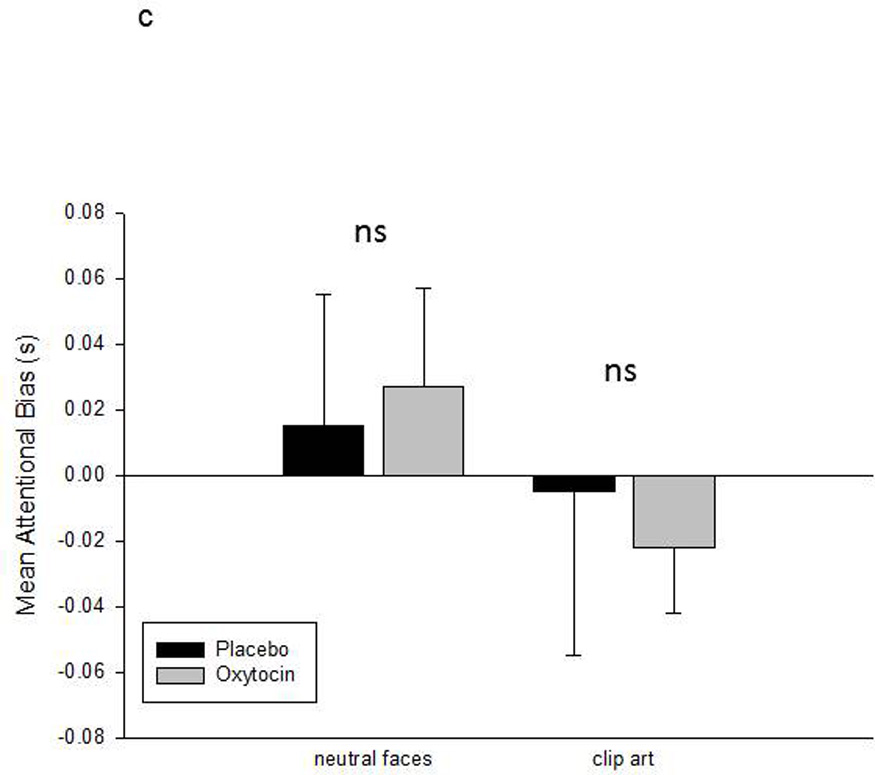

A second analysis used a 2 × 4 repeated measures ANOVA to compare the attentional bias scores across treatment condition (P vs OT) and stimulus category (faces, expressions, gaze direction and clip art). This revealed a significant interaction between treatment condition and stimulus category, F(3,15) = 5.93, p< 0.007, eta2 = 0.54. Follow-up ANOVAs were then used to examine the effect of treatment condition on attentional bias scores within each stimulus category. These revealed a significant effect of treatment on attention to facial expressions, F(1,5) = 14.05, p< 0.02, eta2 = 0.74, and a near significant effect of treatment on attention to the direct vs averted gaze faces, F(1,5) = 5.03, p= 0.075, eta2 = 0.50. Monkeys were slower to respond to the congruent facial expression targets and faster to respond to the direct gaze faces in the IN-OT compared to IN-placebo conditions. No significant effect of treatment condition was observed for either neutral faces or clip art images. Figure 4 shows the mean attentional bias scores (+sem) for each stimulus category in each treatment condition.

Figure 4.

Mean attentional bias scores (+sem) for each of the four stimulus categories in each treatment condition. Attentional bias is calculated as the RT on incongruent trials minus the RT on congruent trials. Positive scores indicate faster RT in the emotionally congruent condition, e.g., neutral faces, facial expressions, direct gaze faces, and clip art. Negative scores indicate faster RT in the incongruent condition, e.g., scrambled images. Asterisks mark significant differences (p< 0.05) in attentional bias scores between the two treatment conditions.

a. Mean attentional bias scores (+sem) for the facial expression trials. This includes a breakdown of the two expression types (bared-teeth and open mouth threat faces) used in this category.

b. Mean attentional bias scores (+sem) for the direct and averted gaze trials. Negative scores indicate faster RT in the incongruent condition, e.g., averted gaze faces.

c. Mean attentional bias scores (+sem) for the neutral faces and clip art images.

To further evaluate the significant decrease in attentional bias to facial expressions in the OT condition, the attentional bias scores were calculated separately for each expression type that was included in the category, e.g., bared-teeth and open mouth threat faces. A paired t-test then compared differences in these scores between treatment conditions. This revealed a significant difference for the open mouth threat faces, t(5) = 2.58, p< 0.05, and a near significant difference for the bared-teeth displays, t(5) = 2.46, p= 0.06. Response times for both expressions categories were reduced after IN-OT administration (see Figure 4).

Several additional hypotheses are possible that evaluate different questions related to the effects of OT on the perception of social and emotional stimuli. Two additional analyses were performed that compared specifically the effect of OT on the emotion quality of visual stimuli, and the social quality of these stimuli. To address the first question, a repeated measures ANOVA compared the effect of treatment condition (OT vs P) on the emotion quality of the stimuli (neutral faces vs facial expressions). This revealed a significant interaction between treatment condition and emotion quality, F(1,5) = 12.72, p< 0.02, eta2 = 0.72. Oxytocin reduced the attentional bias for facial expressions, t(5) = 3.5, p< 0.02, not neutral faces, t(5) = 0.6, p=0.6. To address the second question, a repeated measures ANOVA compared the effect of treatment condition (OT vs P) on the social quality of the stimuli (neutral faces vs clip art). This revealed no significant effects (see Figure 4c). Therefore, the effect of OT on social perception appears to be selective for emotional stimuli, e.g., negative facial expressions, not social stimuli overall.

Finally, the effect of treatment condition on the facial expression trials reported above appears to be inconsistent with the perceptual salience hypothesis. Instead of increasing attentional biases to facial expressions, IN-OT selectively reduced it, resulting in slower response times on the congruent compared to incongruent trials. Figure 5a shows the mean RT for responses to congruent and incongruent facial expression trials in each treatment condition. Interestingly, this figure reveals that after IN-OT treatment, subjects were not only slower to respond to the emotionally congruent targets, but they were faster to respond to the emotionally incongruent targets (scrambled expressions). A repeated measures ANOVA confirmed this effect, finding a significant interaction between the within-subject factors of treatment condition (P vs OT) and trial congruency (congruent vs incongruent) for the facial expression condition, F(1,5) = 12.93, p< 0.02, eta2 = 0.72. This suggests that subjects were actively avoiding facial expressions, slowing their responses on the congruent trials while also speeding up their responses on the incongruent trials. In contrast, Figures 5b and 5c illustrate the mean RT for responding on the congruent and incongruent trials involving neutral faces and clip art, respectively. Repeated measures ANOVAs comparing treatment condition (P vs OT) versus trial congruency (congruent vs incongruent) failed to reveal any significant effects for mean RT on either the neutral face trials or the clip art trials.

Figure 5.

a. Mean RT (+sem) to touch the target on the congruent and incongruent trials in the facial expression condition after placebo or OT administration.

b. Mean RT (+sem) to touch the target on the congruent and incongruent trials in the neutral face condition after placebo or OT administration.

c. Mean RT (+sem) to touch the target on the congruent and incongruent trials in the clip art condition after placebo or OT administration.

Discussion

The present study evaluated the effects of IN-OT and IN-Placebo on social perception in rhesus monkeys using a well-known attention task, the dot-probe task (King et al., 2012; MacLeod et al., 1986). Two interesting findings emerged. First, IN-OT selectively attenuated monkeys’ attention to negative facial expressions, but not neutral faces or nonsocial images, e.g., clip art. This result was not due to an overall reduction in RT performance after OT compared to placebo administration, but was influenced by the congruency between the location of the stimulus image and the target in a treatment-dependent manner. The same pattern of attenuation was found for each individual subject, regardless of age or gender, and irrespective of the magnitude or direction of their overall attentional bias to facial expressions in the placebo condition (see Supplementary Material, Figure S1). It should be noted that these attentional bias scores were as large, or larger, than those reported in human studies (King et al., 2012; Mather & Carstensen, 2003). Additionally, there was a strong trend for IN-OT to reverse subjects’ bias towards attending to averted gaze faces, which are associated with high levels of autonomic arousal in monkeys (Hoffman et al., 2007) and instead increase attention to direct gaze faces depicting the same individual monkey. These results are consistent with several reports in humans showing that IN-OT reduces the aversive, arousing quality of emotional images (Ellenbogen et al., 2012; Normal et al., 2010), increases attention to the eyes in faces (Andari et al., 2010; Guastella et al., 2008), and reduces the amygdala’s response to emotional images (Domes et al., 2007b; Kirsch et al., 2005; Petrovic et al., 2008; Striepens et al., 2012).

The second interesting finding was that the reduced attention to facial expressions after IN-OT treatment was due to both a slowing of RT on the emotionally congruent trials, e.g., when the target was in the same location as the facial expression, and faster RT on the emotionally incongruent trials, e.g., when the target was in the same location as the scrambled image. This suggests that IN-OT was not acting to simply reduce the salience of these important social stimuli, as this explanation would predict reduced attention to facial expressions on the congruent trials, but no differences on attention for the incongruent trials. Instead, these results suggest that subjects actively avoided attending to the facial expressions after IN-OT compared to IN-placebo administration on both types of trials. In contrast, no dissociation was found between RT and treatment condition for the neutral faces or clip art images.

Interestingly, a pattern of results similar to these has been reported previously in a study of age-related changes in emotional perception in healthy humans (Mather & Carstensen, 2003). Using a dot-probe task that paired positive and negative facial expressions, these authors reported reduced attentional biases towards negative facial expressions and faster attentional biases towards positive facial expressions in healthy aged humans compared to young adults. This suggests that the aged subjects were actively avoiding the negative expressions while also seeking out the positive ones. Importantly, these authors demonstrated that this effect was not due to a reduced perceptual salience of the negative images, but rather an active coping strategy by aged individuals to avoid attending to negative or aversive images when encountered (Knight et al., 2007). Moreover, this shift in attentional focus was associated with reduced activation of the amygdala in response to negative stimuli and increased activity in prefrontal cortex, consistent with an active, emotion-regulation strategy (Mather & Carstensen, 2005; Nashiro et al., 2012). The present data suggests that IN-OT may be inducing a similar emotion-regulation strategy in the monkeys, resulting in an active avoidance of the negative facial expressions and averted gaze faces presented in these tasks.

Importantly, the present study does not support an indiscriminant effect of IN-OT on the perception of social stimuli in rhesus monkeys, as the social salience hypothesis suggests. Our studies, for example, did not find any differences in the effect of IN-OT on attention to neutral conspecific faces or the nonsocial clip art images. Thus, OT does not appear to be acting on all social compared to nonsocial images. Instead, the current data suggest that IN-OT acts selectively to modulate subjects’ attentional resources to avoid interacting with negative, aversive, or potentially threatening stimuli in their environment, consistent with numerous studies in humans. Therefore, it may be that IN-OT only affects the perception of the most arousing categories of stimuli, those being the most salient like aversive or threatening images, particularly if the threat is unexpected (Grillon et al., 2012). The present findings are also consistent with predictions of the perceptual salience hypothesis in that IN-OT affects early stages of information processing. Affecting early stages of attentional processing towards negative or arousing information could have profound effects on an individual’s subsequent behavior by freeing valuable attentional and cognitive resources and enabling them to engage instead in prosocial behaviors, including more complex, higher-level socio-cognitive behaviors, like enhanced recall of threatening images, and even enhanced trust and empathy (Bartz et al., 2011; Ellenbogen et al., 2012; Panksepp, 2009; Striepens et al., 2012). Although these results imply that OT is having a strong influence at the level of the amygdala, the distribution of selective OT receptors in the primate brain is unknown (Young et al., 1999). Moreover, a reduction in amygdala activity does not imply an overall reduction in neural responsiveness, but could instead enable enhanced information processing in other interconnected brain regions (Striepens et al., 2012). Among species studied thus far, OT receptor distribution varies broadly and can account for many of the species-typical effects of OT on social behavior (Ross & Young, 2009). So, while OT may have evolved broadly to modulate social information processing and social cognition in many species, the precise manner by which this manifests is presumed to be uniquely adapted to the evolutionary history of each species, and specializations in the interconnectivity between their associated neural networks.

Limitations of this study include the small and heterogeneous sample size (however see Supplementary material), and the ambiguity of the effective dose delivered by the IN nebulizer method. Despite these limitations, together with previous reports in nonhuman primates (Chang et al., 2012), this study confirms the usefulness of an awake intranasal administration protocol for studying the effects of OT on social perception in rhesus monkeys, arguably an ideal model species in which to explore the development of novel pharmacotherapies for treating humans with social impairments, such as ASD. Not only have studies shown that IN-OT can penetrate the CNS in monkeys, but using simple tasks, IN-OT appears to have robust effects on basic cognitive and perceptual processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by MHR01068791 to L.A. Parr, a Neuroscience Initiatives Award from Emory University to L.J. Young, and the Center for Translational Social Neuroscience, Emory University. Additional support was provided by the National Center for Research Resources P51RR000165 to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, currently the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs / OD P51OD011132. Special thanks to Christopher Kanan for providing the scrambling script, Marie Goddette for photographic assistance, and the comments of two anonymous reviewers.

Role of Funding Source

This project was funded by the National Institutes of Health, MHR01068791 to L.A. Parr, a Neuroscience Initiatives Award from Emory University to L.J. Young, and the Center for Translational Social Neuroscience, Emory University. Additional support was provided by the National Center for Research Resources P51RR000165 to the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, currently the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs / OD P51OD011132.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Although the 48IU dose is higher 24IU dose of Syntocinon nasal spray (Novartis, Switzerland) typical of many human studies, much of the aerosol evaporates. So a higher dose was selected for these studies. It should be noted that the reported doses of OT given in primate studies vary widely.

In only one testing session did a subject (Cw) fail to respond on more than 80% of the trials, so she was tested a 2nd time several weeks after the initial session and these data were included in the analysis.

Financial Disclosures

All authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Contributions

LAP conceived of and designed the project, conducted all data analyses, and wrote the paper. MM assisted with the preparation and administration of treatment conditions. MM and LJY contributed to the discussion and assisted with data interpretation. ES collected the data. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Andari E, Duhamel J, Zalla T, Herbrecht E, Leboyer M, Sirigu A. Promoting social behavior with oxytocin in high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. PNAS. 2010;107:4389–4394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910249107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychonom Bull. 2007;133:1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartz JA, Zaki J, Bolger N, Ochsner KN. Social effects of oxytocin in humans: context and person matter. TICS. 2011;15:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner T, Heinrichs M, Vonlanthen A, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin shapes the neural circuitry of trust and trust adaptation in humans. Neuron. 2008;58:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born J, Lange T, Kern W, McGregor GP, Bickel U, Fehm HL. Sniffing neuropeptides: A transnasal approach to the human brain. Nature neurosci. 2002;5:514–516. doi: 10.1038/nn849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SW, Barter JW, Ebitz RB, Watson KK, Platt ML. Inhaled oxytocin amplifies both vicarious reinforcement and self-reinforcement in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) PNAS. 2012;109:959–964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114621109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchland PS, Winkielman P. Modulating social behavior with oxytocin: How does it work? What does it mean? Horm & Behav. 2012;61:392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu CK, Greer LL, Handgraaf MJ, Shalvi S, Van Kleef GA, Bass M, Ten Velden FS, Van Dijk E, Feith SW. The neuropeptide oxytocin regulates parochial altruism in intergroup conflict among humans. Science. 2010;328:1408–1411. doi: 10.1126/science.1189047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FBM, Luttrell LM. The similarity principle underlying social bonding among female rhesus monkeys. Folia Primatol. 1986;46:215–234. doi: 10.1159/000156255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domes G, Heinrichs M, Michel A, Berger C, Herpertz SC. Oxytocin improves “mind-reading” in humans. Biol Psychiat. 2007a;61:731–733. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domes G, Heinrichs M, Glascher J, Buchel C, Braus DF, Herpertz S. Oxytocin attenuates amygdala responses to emotional faces regardless of valence. Biol Psychiat. 2007b;62:1187–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbogen MA, Linnen A, Grumet R, Cardoso C, Joober R. The acute effects of intranasal oxytocin on automatic and effortful attentional shifting to emotional faces. Psychophysiol. 2012;49:128–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer-Shofty M, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Harari H, Levkovitz Y. The effect of intranasal administration of oxytocin on fear recognition. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamer M, Zurowski B, Buchel C. Different amygdala subregions mediate valence-related and attentional effects of oxytocin in humans. PNAS. 2010;107:9400–9405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000985107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Krimsky M, Charney Dr, Vytal K, Ernst M, Cornwell B. Oxytocin increases anxiety to unpredictable threat. 2012:1–2. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.156. Mol. Psychiat. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella AJ, Mitchell PB, Dadds MR. Oxytocin increases gaze to the eye region of human faces. Biol Psychiat. 2008;63:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella AJ, Einfeld SL, Gray KM, Rinehart NJ, Tonge BJ, Lamber tTJ, Hickie IB. Intranasal oxytocin improves emotion recognition for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:692–694. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Gothard KM, Schmid MC, Logothetis NK. Facial-expression and gaze-selective responses in the monkey amygdala. Curr Biol. 2007;17:766–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Novotny S, Hanratty M, Yaffe R, DeCaria CM, Aronowitz BR, Mosovich S. Oxytocin infusion reduces repetitive behaviors in adults with autistic and Asperger’s disorders. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;28:193–198. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlemann R, Patin A, Onur OA, Cohen MX, Baumgartner T, Metzler S, Dziobek I, Gallinat J, Wagner M, Maier W, Kendrick KM. Oxytocin enhances amygdala-dependent, socially reinforced learning and emotional empathy in humans. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4999–5007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5538-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito TA, Larsen JT, Smith NK, Cacioppo JT. Negative information weighs more heavily on the brain: the negativity bias in evaluative categorizations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;75:887–900. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.4.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King HM, Kurdziel LB, Meyer JS, Lacreuse A. Effects of testosterone on attention and memory for emotional stimuli in male rhesus monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2012;37:396–409. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch P, Esslinger C, Chen Q, Mier D, Lis S, Siddhanti S, Gruppe H, Mattay VS, Gallhofer B, Meyer-Lindenberg A. Oxytocin modulates neural circuitry for social cognition and fear in humans. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11489–11493. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3984-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M, Seymour TL, Gaunt JT, Baker C, Nesmith K, Mather M. Aging and goal-directed emotional attention: distraction reverses emotional biases. Emotion. 2007;7:705–714. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.4.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosfeld M, Heinrichs M, Zak PJ, Fischbacher U, Fehr E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature. 2005;435:673–676. doi: 10.1038/nature03701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster EHW, Crombez G, Verschuere B, De Houwer J. Selective attention to threat in the dot probe paradigm: differentiating vigilance and difficulty to disengage. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:1183–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod C, Mathews A, Tata P. Attentional bias in emotional disorders. J Ab Psychol. 1986;95:15–20. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and attentional bias to emotional faces. Psychol Sci. 2003;14:409–415. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.01455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Carstensen LL. Aging and motivated cognition: the positivity effect in attention and memory. TICS. 2005;9:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi ME, Young LJ. The oxytocin system in drug discovery for autism: Animal models and novel therapeutic strategies. Horm & Behav. 2012;61:340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi ME, Connor-Stroud F, Landgraf R, Young LJ, Parr LA. Penetrance of peripheral oxytocin into the lumbar cerebrospinal fluid of rhesus monkeys via multiple routes of administration. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Nashiro K, Sakaki M, Mather M. Age differences in brain activity during emotional processing: reflections of age-related decline or increased emotion regulation? Gerontol. 2012;58:156–163. doi: 10.1159/000328465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann ID. Brain oxytocin: A key regulator of emotional and social behaviours in both females and males. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:858–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GJ, Cacioppo JT, Morris JS, Karelina K, Malarkey WB, DeVries AC, Berntson GG. Selective influences of oxytocin on the evaluative processing of social stimuli. J Psychopharm. 2011;25:1313–1319. doi: 10.1177/0269881110367452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohman A, Lundqvist D, Esteves F. The face in the crowd revisited: a threat advantage with schematic stimuli. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;80:381–396. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.80.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. Primary process affects and brain oxytocin. Biological Psychiat. 2009;65:725–727. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr LA, Heintz M. Facial expression recognition in rhesus monkeys. Anim Behav. 2009;77:1507–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr LA. The evolution of face processing in primates. Phil Trans R Soc London, B. 2011;366:1764–1777. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic P, Kalisch R, Singer T, Dolan RJ. Oxytocin attenuates affective evaluations of conditioned faces and amygdala activity. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6607–6615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4572-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmele U, Hediger K, Heinrichs M, Klaver P. Oxytocin makes a face in memory familiar. J Neurosci. 2009;29:38–42. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4260-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HE, Young LJ. Oxytocin and the neural mechanisms regulating social cognition and affiliative behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:534–547. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito A, Nakamura K. Oxytocin changes primate paternal tolerance to offspring in food transfer. J Comp Physiol. 2011;197:329–337. doi: 10.1007/s00359-010-0617-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaskan E, Ehrhardt R, Schulz A, Walter M, Schachinger H. Post-learning intranasal oxytocin modulates human memory for facial identity. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2008;33:368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheele D, Striepens N, Gunturkun 0, Deutschlander S, Maier W, Kendrick KM, Hurlemann R. Oxytocin modulates social distance between males and females. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:16074–16079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2755-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Snozzi R, Bird G, Petrovic P, Silani G, Heinrichs M, Dolan RJ. Effects of oxytocin and prosocial behavior on brain responses to direct and vicariously experienced pain. Emotion. 2008;8:781–791. doi: 10.1037/a0014195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AS, Agmo A, Birnie AK, French JA. Manipulation of the oxytocin system alters social behavior and attraction in pair-bonding prmates, Callithrix penicillata. Horm & Behav. 2010;57:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striepens N, Scheele D, Kendrick KM, Becker B, Schafer L, Schwalba K, Reul J, Maier W, Hurlemann R. Oxytocin facilitates protective responses to aversive social stimuli in males. PNAS. 2012;109:18144–18149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208852109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodoridou A, Rowe AC, Penton-Voak IS, Rogers PJ. Oxytocin and social perception: Oxytocin increases perceived facial trustworthiness and attractiveness. Horm & Behav. 2009;56:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller BM, Dunbar RIM. Differential behavioural effects of silent bared teeth display and relaxed open mouth display in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Ethology. 2005;111:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Winslow JT, Insel TR. Social status in pairs of male squirrel monkeys determines the behavioral response to central oxytocin administration. J Neurosci. 1991;11:2032–2038. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-07-02032.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ, Toloczko D, Insel TR. Localization of vasopressin (V1a) receptor binding and mRNA in the rhesus monkey. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:291–297. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.