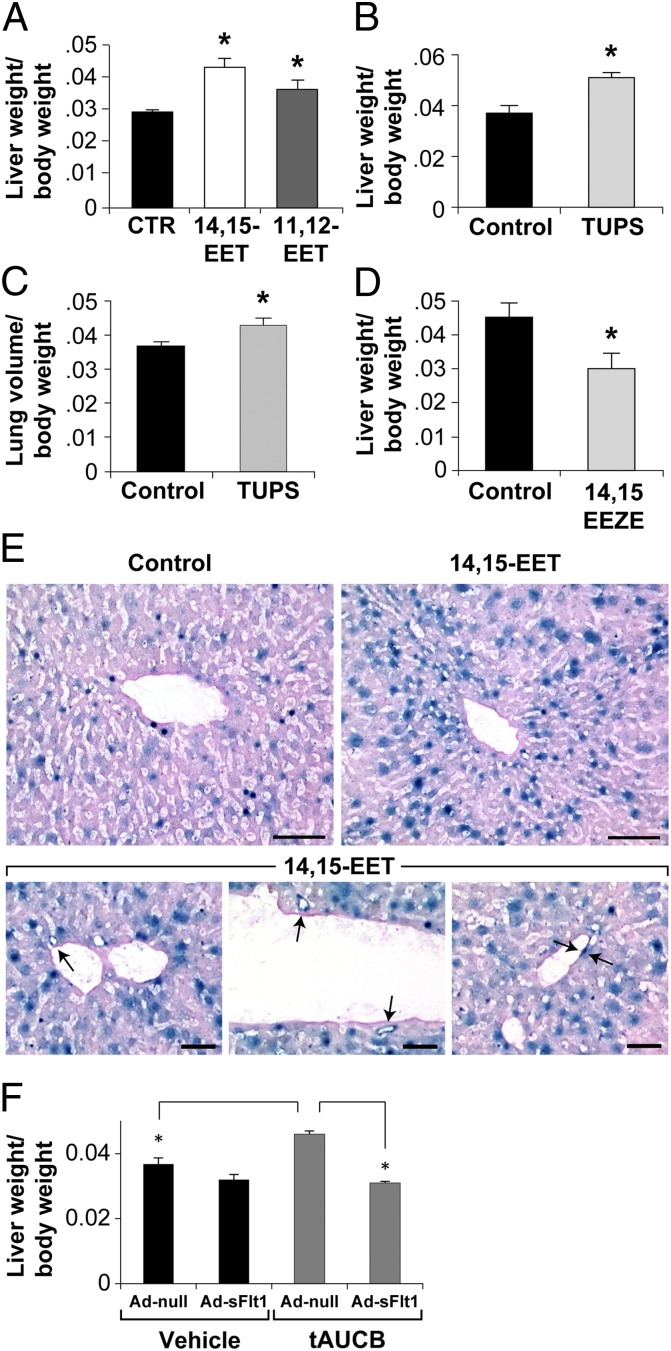

Fig. 2.

Pharmacological manipulation of EETs and their action in organ regeneration. (A) Systemic administration of 14,15- or 11,12-EET (15 μg⋅kg−1⋅d−1) via minipump stimulates liver regeneration on day 4 after partial hepatectomy compared with vehicle-treated mice. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle. (B) The sEHi TUPS increases liver regeneration at day 4 after partial hepatectomy. TUPS was given at a dose of 10 mg⋅kg−1⋅d−1. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. control. (C) The sEHi TUPS increases lung regeneration at day 4 after partial pneumonectomy. TUPS was given at a dose of 10 mg⋅kg−1⋅d−1. n = 5 or 6 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. control. (D) Systemic administration of the EET antagonist 14,15-EEZE (0.21 mg per mouse) inhibits liver regeneration on day 7 after partial hepatectomy. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. control. (E) Regenerating livers in VEGF–LacZ-Tr mice treated with 14,15-EET (15 μg⋅kg−1⋅d−1) show β-galactosidase staining (marker of VEGF production) in sinusoidal and venous ECs (arrows) and hepatocytes. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (F) VEGF depletion with Ad-sFlt suppresses EET-induced liver regeneration by the sEHi tAUCB but has no effect on vehicle-treated liver regeneration. n = 5 mice per group. *P < 0.05.