Abstract

Cystic dilatations of the bile ducts may be found along the extrahepatic biliary tree, within the liver, or in both of these locations simultaneously. Presentation in adults is often associated with complications. The therapeutic possibilities have changed considerably over the last few decades. If possible, complete resection of the cyst(s) can cure the symptoms and avoid the risk of malignancy. According to the type of bile duct cyst, surgical procedures include the Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy and variable types of hepatic resection. However, the diffuse forms of Todani type V cysts (Caroli disease and Caroli syndrome) in particular remain a therapeutic problem, and liver transplantation has become an important option. The mainstay of interventional treatment for Todani type III bile duct cysts is via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. The diagnostic term “bile duct cyst” comprises quite different pathological and clinical entities. Interventional therapy, hepatic resection, and liver transplantation all have their place in the treatment of this heterogeneous disease group. They should not be seen as competitive treatment modalities, but as complementary options. Each patient should receive individualized treatment after all of the clinical findings have been considered by an interdisciplinary team.

Keywords: Bile duct cyst, Caroli syndrome, Caroli disease, Hepatic resection, Liver transplantation, Interventional treatment

Core tip: This is an invited editorial on the role of different treatment options for patients with bile duct cysts. It is not meant to be a thorough review on the numerous aspects of this disease, but instead intends to provide critical insights into current developments in interventional and surgical therapies, defining their potential and indicating that they should not be seen as competitive but as complementary options. The diagnostic term “bile duct cyst” comprises quite different pathological and clinical entities. Interventional therapy, hepatic resection, and liver transplantation all have their place in the treatment of this heterogeneous disease group.

INTRODUCTION

The modified Todani[1,2] classification that is widely used for bile duct cysts has several drawbacks. In particular, it combines different disease processes and does not account for the risk of malignant transformation or differences in epidemiology, pathogenesis, complications, and treatment. As a result, its clinical significance has been the subject of critical discussion and further modifications have been proposed. Moreover, there is uncertainty on the categorization of some variants.

Type I bile duct cysts comprise the subtypes IA (cystic dilatation of the common bile duct), IB (segmental dilatation of the common bile duct), and IC (fusiform dilatation extending to the common hepatic duct). Type II is a true diverticulum in the extrahepatic duct (supraduodenal). Type III is a choledochocele confined to the common bile duct within the duodenal wall. An important differential diagnosis for a type III cyst is a juxtapapillary duodenal diverticulum. Type IV is divided into type IVa (multiple intra- and extrahepatic bile duct cysts) and type IVb (multiple extrahepatic bile duct cysts, which are less common than type IVa). Finally, type V corresponds to Caroli disease (single or multiple intrahepatic bile duct cysts). When associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis, type V is termed Caroli syndrome and is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait[3-5].

Caroli disease (CD) and Caroli syndrome (CS) are part of a broader spectrum of diseases with ductal plate malformations. These diseases have a close relationship with congenital kidney disorders, notably autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease[6]. Generally, Caroli syndrome is characterized by early onset, with rapid disease progression due to the combination of cholangitis and portal hypertension[7-9]. Ductal plate malformations affect different levels of the intrahepatic biliary tree, including the large and proximal ducts in CD, the smaller ducts in CS and congenital hepatic fibrosis, and the more peripheral interlobular ducts in polycystic liver disease and von Meyenburg complexes[10,11]. Type V cysts can be considered as a distinct disease entity from types I-IV, and type III might be an anatomical variation rather than a true dilatation of the common bile duct[12]. Indeed, Ziegler et al[13] suggested that the classification of bile duct cysts should not include choledochoceles (type III), as they differ from choledochal cysts with respect to age, gender, presentation, pancreatic duct anatomy, and their management.

Michaelides et al[14] described a dilatation of the central portion of the cystic duct apart from the dilatation of the common hepatic and common bile duct, giving the cyst a bicornal configuration. They suggested classifying this finding as a further subtype of Todani I cysts, namely Todani ID. However, Calvo-Ponce et al[15] have already proposed Todani ID as a cyst above the junction of the common hepatic duct and the cystic duct.

Okada et al[16] described a “common channel syndrome” and Lilly et al[17] used the term “forme fruste choledochal cyst” for a long common channel secondary to a proximal junction of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct with stenosis of the distal common bile duct, combined with cholecystitis and the classical pathological features of a choledochal cyst in the wall of the common bile duct. Forme fruste choledochal cysts are associated with only minimal or no dilatation of the extrahepatic bile duct, pancreaticobiliary maljunction, and protein plugs or debris in the common channel[18-20]. The cut-off diameter of the extrahepatic bile duct above which the diagnosis of a forme fruste is unacceptable has been arbitrarily described as 10 mm[20].

Kaneyama et al[21] reported variants with a type II diverticulum arising from a type IC bile duct cyst, resulting in “mixed type I and II” cysts. Visser et al[22] argued that all varieties of type I bile duct cysts have some element of intrahepatic dilatation. They concluded that type I and IVa cysts only differ in terms of the extent of intrahepatic dilation, which makes discriminating between these two types rather arbitrary. Furthermore, an additional category, termed type VI, has been used for cystic malformations of the cystic duct[23,24]. However, these cysts could also be classified as a subtype of type II[25]. Loke et al[26] described diverticular cysts of the cystic duct, whereas Wang et al[27] reported a patient with type I and type III choledochal cysts that occurred simultaneously.

Notwithstanding these drawbacks, the crucial advantages of the Todani classification are its widespread use and reproducibility, which allow comparisons among the various published studies that have been built upon it. Therefore, its further use is to be advocated, despite its shortcomings. For this reason, the Todani system is also used in this editorial as a background for the therapeutic considerations.

INTERVENTIONAL TREATMENT

For type III bile duct cysts, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is an important diagnostic tool, and interventional therapy via ERCP is the mainstay of treatment. For the diagnosis of the other types, the less-invasive magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) has widely replaced ERCP and represents the “gold standard” approach. However, ERCP remains the imaging modality of choice for type III cysts because it also enables a simultaneous therapeutic sphincterotomy to be performed. Originally, type III cysts were treated by transduodenal excision and sphincteroplasty; however, endoscopic sphincterotomy is now considered to be sufficient. Ohtsuka et al[28] reported malignancies in 3 out of 11 patients with type III cysts. Therefore, endoscopic surveillance is recommended. Interventional therapy with ERC and shock-wave lithotripsy, in addition to antibiotics and bile acid treatment (ursodeoxycholic acid, UDCA)[29], is also used for type V cysts, but cannot be expected to be curative. Its success is usually only temporary, and recurrent episodes of cholangitis cannot be prevented[30]. Internal biliary stents have also been described as a therapeutic option in anecdotal case reports[31,32].

A crucial argument against long-term treatment with interventional techniques and for removal of the cyst is the increased risk of malignancy. About 2.5%-17.5% of patients with bile duct cysts develop malignancies, and this incidence increases with age[33]. In a series of 38 adult patients published by Visser et al[22], 21% developed malignancies. The underlying mechanisms that cause carcinogenesis may be complex, as a consequence of chronic inflammation, cell regeneration, and DNA breaks leading to dysplasia. Pancreatic reflux might also play a role in causing K-ras mutations, cellular atypia, and the overexpression of p53[34]. Malignancy in Caroli disease has been reported to occur in 7%-15% of patients[33], underlining the need for surgery and surveillance.

RESECTION

Complete resection of cysts and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (RYHJ) is the procedure of choice for type I and IVb bile duct cysts. The success rate of this approach has been reported as 92%[35]. If adequate, the procedure may be performed laparoscopically. The benefits of the laparoscopic approach are also underlined in the reports by Gander et al[36] and by Palanivelu et al[37]. Potential complications of RYHJ include cholangitis, pancreatitis, biliary calculi, and, rarely, malignancy. Watanabe et al[38] reported that malignancy occurred in less than 1% of patients after a previous cyst excision, but higher incidences have been observed that may be due to incomplete cyst removal. Postoperative complications are usually seen in patients with inflammation and fibrosis at the time of surgery.

For forme fruste choledochal cysts, excision of the malformed ductal tissue with biliary reconstruction is required, as cholecystectomy alone is an inadequate treatment[39].

In all cases, complete removal of the cyst makes a decisive difference. With incomplete removal, Liu et al[40] reported a malignancy rate of 33.3%, compared to 6% after complete resection. Simple excision may be feasible for type II cysts, with ligation at the neck and without the need for biliary reconstruction. If possible, a laparoscopic approach may be advantageous[41].

For type IVa cysts, a tailored approach is necessary. Visser et al[22] suggested that excision of the extrahepatic component with hepaticojejunostomy should be performed; however, in cases with symptomatic intrahepatic affections (with stones, cholangitis, or biliary cirrhosis), treatment should correspond to that used for type V cysts, with hepatic resection for localized disease and transplantation for diffuse forms.

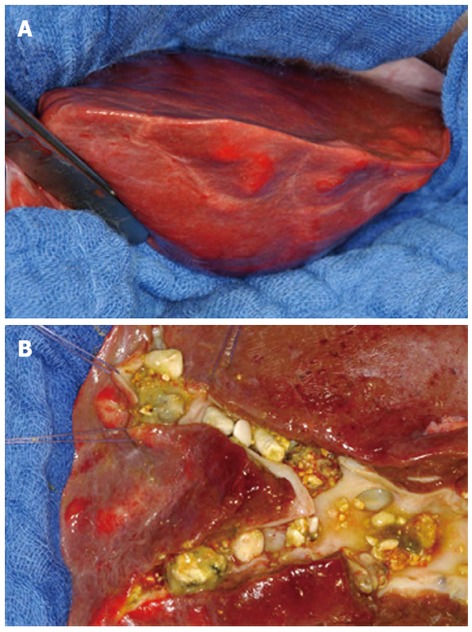

Although reported numbers in the literature are low, there is broad consensus that hepatic resection is the therapy of choice in patients with localized forms of type V cysts (Figure 1). If patients with monolobar disease remain asymptomatic, they will only require supportive dissolution therapy and surveillance; however, the risk of malignancy also has to be considered. For example, Kassahun et al[42] determined a cholangiocarcinoma incidence of 9.7%, whereas Ulrich et al[30] reported 9.1% and Bockhorn et al[43] reported 25%.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative picture (A) and a detailed view (B) of the operative specimen (left hepatic lobe) in a patient with Todani type V bile duct cysts.

In symptomatic patients with acute cholangitis, a variable symptom-free interval may be achieved by using antibiotic treatment with or without endoscopic sphincterotomy and calculi removal or lithotripsy. However, most of these patients will develop recurrent cholangitis, chronic inflammation, and an increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma. These patients are best treated by liver resection if their hepatic function is preserved and there are no contraindications to liver surgery.

In earlier publications, a rather small proportion of monolobar disease (20%-25%) was described, with almost 90% of these cases located in the left hepatic lobe. Due to small patient numbers, the prevalence of localized CD may have been underestimated. Recent studies indicate higher percentages (80%) of patients with localized disease[30,42] and a more variable distribution of disease between the left and right lobes.

TRANSPLANTATION

Diffuse forms of type V cysts (CD and CS) remain a therapeutic problem. In patients with these cysts, combined procedures with partial hepatectomy and biliodigestive anastomoses[44,45] have been described, but transplantation offers the only curative option. The progression of congenital hepatic fibrosis in CS and the development of secondary biliary cirrhosis in patients with CD may also lead to portal hypertension that is not treatable by conservative means. De Kerckhove et al[46] reported congenital hepatic fibrosis in 27% of their patients and the primary indication for orthotopic liver transplantation was recurrent cholangitis (90%).

An important argument for liver transplantation is the avoidance of cholangiocarcinoma development[47]. Concerns include the choice of an appropriate time point for transplantation, procedural risks, and the use of immunosuppression in young and otherwise healthy individuals. Potential postoperative complications include rejection and vascular thrombosis[46]. Pre-transplant workup of these patients for occult cholangiocarcinoma is crucial. In patients with associated polycystic kidneys and renal failure, immunosuppression after kidney transplantation may predispose to severe cholangitis, and therefore, combined liver/kidney transplantation should be considered. The results of liver transplantation for diffuse forms of type V cysts compare favorably with those of transplantations for other indications. In the review carried out by Millwala et al[48], the overall graft and patient survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 79.9%, 72.4% and 72.4%, and 86.3%, 78.4% and 77%, respectively; living donor transplantation was performed in 3.8% of cases. In the single-center study by Habib et al[49], overall graft and patient survival rates at 1, 5, and, 10 years were reported as 73%, 62%, and 53%, and 76%, 65% and 56%, respectively.

In conclusion, the diagnostic term “bile duct cyst” comprises quite different pathological and clinical entities. Interventional therapy, hepatic resection, and transplantation all have their place in the treatment of this heterogeneous disease group. They should not be seen as competitive, but complementary options. In spite of several shortcomings, the modified Todani classification offers a basis for treatment planning and for comparing results reported in the literature. Each patient, however, should receive tailored individual treatment after all findings have been discussed by an interdisciplinary team.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Cucchetti A, Kim DG S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor Rutherford A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: Classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty-seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg. 1977;134:263–269. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todani T, Watanabe Y, Toki A, Morotomi Y. Classification of congenital biliary cystic disease: special reference to type Ic and IVA cysts with primary ductal stricture. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:340–344. doi: 10.1007/s00534-002-0733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caroli J, Couinaud C, Soupault R, Porcher P, Eteve J. [A new disease, undoubtedly congenital, of the bile ducts: unilobar cystic dilation of the hepatic ducts] Sem Hop. 1958;34:496–502/SP. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caroli J, Soupault R, Kossakowski J, Plocker L. [Congenital polycystic dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts; attempt at classification] Sem Hop. 1958;34:488–95/SP. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caroli J, Corcos V. [Congenital dilatation of the intrahepatic bile ducts] Rev Med Chir Mal Foie. 1964;39:1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lefere M, Thijs M, De Hertogh G, Verslype C, Laleman W, Vanbeckevoort D, Van Steenbergen W, Claus F. Caroli disease: review of eight cases with emphasis on magnetic resonance imaging features. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:578–585. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283470fcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keramidas DC, Kapouleas GP, Sakellaris G. Isolated Caroli’s disease presenting as an exophytic mass in the liver. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;13:177–179. doi: 10.1007/s003830050281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harjai MM, Bal RK. Caroli syndrome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2000;16:431–432. doi: 10.1007/s003839900323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sylvestre PB, El-Youssef M, Freese DK, Ishitani MB. Caroli’s syndrome in a 1-year-old child. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:59. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desmet VJ. Ludwig symposium on biliary disorders--part I. Pathogenesis of ductal plate abnormalities. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:80–89. doi: 10.4065/73.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato Y, Harada K, Kizawa K, Sanzen T, Furubo S, Yasoshima M, Ozaki S, Ishibashi M, Nakanuma Y. Activation of the MEK5/ERK5 cascade is responsible for biliary dysgenesis in a rat model of Caroli’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:49–60. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62231-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arenas-Jiménez JJ, Gómez-Fernández-Montes J, Mas-Estellés F, Cortina-Orts H. Large choledochocoele: difficulties in radiological diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29:807–810. doi: 10.1007/s002470050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziegler KM, Pitt HA, Zyromski NJ, Chauhan A, Sherman S, Moffatt D, Lehman GA, Lillemoe KD, Rescorla FJ, West KW, et al. Choledochoceles: are they choledochal cysts? Ann Surg. 2010;252:683–690. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181f6931f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michaelides M, Dimarelos V, Kostantinou D, Bintoudi A, Tzikos F, Kyriakou V, Rodokalakis G, Tsitouridis I. A new variant of Todani type I choledochal cyst. Imaging evaluation. Hippokratia. 2011;15:174–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvo-Ponce JA, Reyes-Richa RV, Rodríguez Zentner HA. Cyst of the common hepatic duct: treatment and proposal for a modification of Todani’s classification. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okada A, Nagaoka M, Kamata S, Oguchi Y, Kawashima Y, Saito R. “Common channel syndrome”--anomalous junction of the pancreatico-biliary ductal system. Z Kinderchir. 1981;32:144–151. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1063249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lilly JR, Stellin GP, Karrer FM. Forme fruste choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 1985;20:449–451. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(85)80239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyano T, Ando K, Yamataka A, Lane G, Segawa O, Kohno S, Fujiwara T. Pancreaticobiliary maljunction associated with nondilatation or minimal dilatation of the common bile duct in children: diagnosis and treatment. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1996;6:334–337. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas S, Sen S, Zachariah N, Chacko J, Thomas G. Choledochal cyst sans cyst--experience with six “forme fruste” cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:247–251. doi: 10.1007/s003830100675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimotakahara A, Yamataka A, Kobayashi H, Okada Y, Yanai T, Lane GJ, Miyano T. Forme fruste choledochal cyst: long-term follow-up with special reference to surgical technique. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1833–1836. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaneyama K, Yamataka A, Kobayashi H, Lane GJ, Miyano T. Mixed type I and II choledochal cyst: a new clinical subtype? Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:911–913. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visser BC, Suh I, Way LW, Kang SM. Congenital choledochal cysts in adults. Arch Surg. 2004;139:855–860; discussion 860-862. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.8.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maheshwari P. Cystic malformation of cystic duct: 10 cases and review of literature. World J Radiol. 2012;4:413–417. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i9.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De U, Das S, Sarkar S. Type VI choledochal cyst revisited. Singapore Med J. 2011;52:e91–e93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dumitrascu T, Lupescu I, Ionescu M. The Todani classification for bile duct cysts: an overview. Acta Chir Belg. 2012;112:340–345. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2012.11680849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loke TK, Lam SH, Chan CS. Choledochal cyst: an unusual type of cystic dilatation of the cystic duct. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:619–620. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.3.10470889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang QG, Zhang ST. A rare case of bile duct cyst. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2550–2551. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohtsuka T, Inoue K, Ohuchida J, Nabae T, Takahata S, Niiyama H, Yokohata K, Ogawa Y, Yamaguchi K, Chijiiwa K, et al. Carcinoma arising in choledochocele. Endoscopy. 2001;33:614–619. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-15324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caroli-Bosc FX, Demarquay JF, Conio M, Peten EP, Buckley MJ, Paolini O, Armengol-Miro JR, Delmont JP, Dumas R. The role of therapeutic endoscopy associated with extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy and bile acid treatment in the management of Caroli’s disease. Endoscopy. 1998;30:559–563. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ulrich F, Pratschke J, Pascher A, Neumann UP, Lopez-Hänninen E, Jonas S, Neuhaus P. Long-term outcome of liver resection and transplantation for Caroli disease and syndrome. Ann Surg. 2008;247:357–364. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815cca88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciambotti GF, Ravi J, Abrol RP, Arya V. Right-sided monolobar Caroli’s disease with intrahepatic stones: nonsurgical management with ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:761–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold DM, Stark B, Pettei MJ, Levine JJ. Successful use of an internal biliary stent in Caroli’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:589–592. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhavsar MS, Vora HB, Giriyappa VH. Choledochal cysts: a review of literature. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:230–236. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.98425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwasaki Y, Shimoda M, Furihata T, Rokkaku K, Sakuma A, Ichikawa K, Fujimori T, Kubota K. Biliary papillomatosis arising in a congenital choledochal cyst: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:1019–1022. doi: 10.1007/s005950200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tao KS, Lu YG, Wang T, Dou KF. Procedures for congenital choledochal cysts and curative effect analysis in adults. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2002;1:442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gander JW, Cowles RA, Gross ER, Reichstein AR, Chin A, Zitsman JL, Middlesworth W, Rothenberg SS. Laparoscopic excision of choledochal cysts with total intracorporeal reconstruction. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:877–881. doi: 10.1089/lap.2010.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Parthasarathi R, Amar V, Senthilnathan P. Laparoscopic management of choledochal cysts: technique and outcomes--a retrospective study of 35 patients from a tertiary center. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe Y, Toki A, Todani T. Bile duct cancer developed after cyst excision for choledochal cyst. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6:207–212. doi: 10.1007/s005340050108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyano G, Yamataka A, Shimotakahara A, Kobayashi H, Lane GJ, Miyano T. Cholecystectomy alone is inadequate for treating forme fruste choledochal cyst: evidence from a rare but important case report. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:61–63. doi: 10.1007/s00383-004-1266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu YB, Wang JW, Devkota KR, Ji ZL, Li JT, Wang XA, Ma XM, Cai WL, Kong Y, Cao LP, et al. Congenital choledochal cysts in adults: twenty-five-year experience. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120:1404–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang DC, Liu ZP, Li ZH, Li DJ, Chen J, Zheng SG, He Y, Bie P, Wang SG. Surgical treatment of congenital biliary duct cyst. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kassahun WT, Kahn T, Wittekind C, Mössner J, Caca K, Hauss J, Lamesch P. Caroli’s disease: liver resection and liver transplantation. Experience in 33 patients. Surgery. 2005;138:888–898. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bockhorn M, Malagó M, Lang H, Nadalin S, Paul A, Saner F, Frilling A, Broelsch CE. The role of surgery in Caroli’s disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:928–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barker EM, Kallideen JM. Caroli’s disease: successful management using permanent-access hepaticojejunostomy. Br J Surg. 1985;72:641–643. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aeberhard P. Surgical management of Caroli’s disease involving both lobes of the liver. Br J Surg. 1985;72:651–652. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Kerckhove L, De Meyer M, Verbaandert C, Mourad M, Sokal E, Goffette P, Geubel A, Karam V, Adam R, Lerut J. The place of liver transplantation in Caroli’s disease and syndrome. Transpl Int. 2006;19:381–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang ZX, Yan LN, Li B, Zeng Y, Wen TF, Wang WT. Orthotopic liver transplantation for patients with Caroli’s disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Millwala F, Segev DL, Thuluvath PJ. Caroli’s disease and outcomes after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:11–17. doi: 10.1002/lt.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Habib S, Shaikh OS. Caroli’s disease and liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:2–3. doi: 10.1002/lt.21379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]