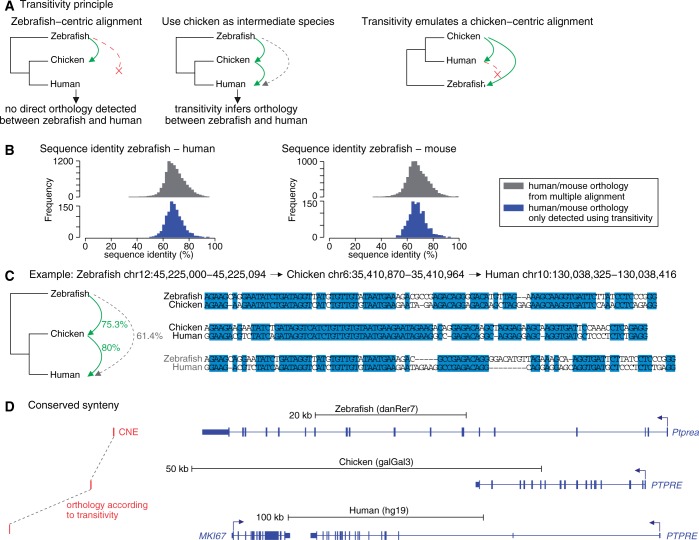

Figure 3.

Transitivity can reveal orthology between distant genomes that is not directly visible. (A) Illustration of the transitivity principle. A zebrafish locus aligns to chicken but not directly to human. However, the chicken locus does align to human, allowing us to infer orthology and anchor an alignment between zebrafish and human. Conceptually, transitivity mimics a multiple alignment using the intermediate species as the reference species. (B) Sequence identity of zebrafish—human/mouse alignments, separating those alignments found only using transitivity (blue) and those directly aligning in the syntenic multiple alignments (gray), suggests that transitivity-inferred alignments also evolve under clear purifying selection. (C) An example where zebrafish has a weaker alignment to human that is not detected in the genome-wide pipeline. However, an anchored alignment using chicken as an intermediate species shows clear orthology between the diverged zebrafish and human sequence. (D) The CNE shown in (C) is in synteny with the PTPRE gene in all three species.