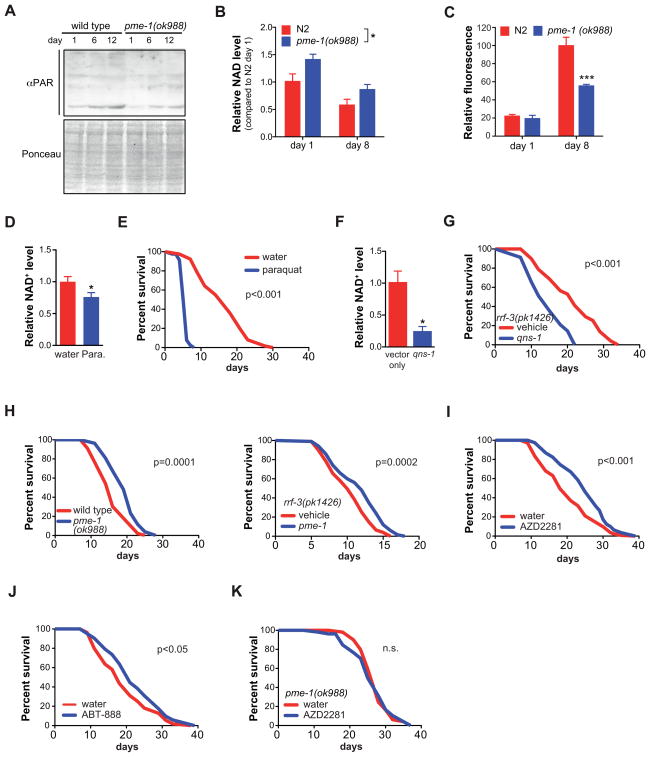

Figure 1. NAD+ is causally involved in aging.

(A) Aged C. elegans displayed higher total protein PARylation levels, which were largely attenuated in pme-1 mutants. Ponceau staining is used as a loading control.

(B) Aging decreased worm NAD+ levels, in both wildtype and in pme-1 mutant worms, with a higher level of NAD+ in the pme-1 mutant during aging. Two-way ANOVA indicated significant difference with age (p<0.008) and genotype (p=0.02).

(C) pme-1 mutant worms accumulated less of the aging pigment lipofuscin compared to wild type worms.

(D–E) Supplementation of N2 wild type worms with 4 mM paraquat depletes NAD+ levels (D) and shortens lifespan (E).

(F–G) RNAi against qns-1, encoding NAD+ synthase, depletes NAD+ levels (F) and shortens lifespan in worms (G)

(H) pme-1(ok988) mutant worms show a 29% mean lifespan extension (left panel) while pme-1 RNAi in the rrf-3(pk1426) strain extends lifespan by 20% (right panel).

(I–J) PARP inhibition by either AZD2281 (100 nM) or ABT-888 (100 nM) extended worm lifespan respectively by 22.9% (I) and 15% (J).

(K) The lifespan extension of AZD2281 is pme-1-dependent.

Bar graphs are expressed as mean±SEM, * p≤0.05; ** p≤0.01; *** p≤0.001. For lifespan curves, p-values are shown in the graph (n.s. = not significant).

See also Figure S1 and S2A–B. See Table S1 and S2 for additional detail on the lifespan experiments.