Abstract

The Drosophila Eyes Absent Homologue 1 (EYA1) is a component of the retinal determination gene network (RDGN) and serves as an H2AX phosphatase. The cyclin D1 gene encodes the regulatory subunits of a holoenzyme that phosphorylates and inactivates the pRb protein. Herein, comparison with normal breast demonstrated EYA1 is overexpressed with cyclin D1 in luminal B breast cancer subtype. EYA1 enhanced breast tumor growth in mice in vivo requiring the phosphatase domain. EYA1 enhanced cellular proliferation, inhibited apoptosis, and induced contact-independent growth and cyclin D1 abundance. The induction of cellular proliferation and cyclin D1 abundance, but not apoptosis, was dependent upon the EYA1 phosphatase domain. The EYA1-mediated transcriptional induction of cyclin D1 occurred via the AP-1 binding site at −953 and required the EYA1 phosphatase function. The AP-1 mutation did not affect SIX1-dependent activation of cyclin D1. EYA1 was recruited in the context of local chromatin to the cyclin D1 AP-1 site. The EYA1 phosphatase function determined the recruitment of CBP, RNA polymerase II and acetylation of H3K9 at the cyclin D1 gene AP-1 site regulatory region in the context of local chromatin. The EYA1 phosphatase regulates cell cycle control via transcriptional complex formation at the cyclin D1 promoter.

Introduction

The Drosophila Eyes Absent Homologue 1 (EYA1) is a component of the retinal determination gene network (RDGN) involved in organismal development (1, 2). The cell fate determination gene network includes the dachshund (dac), twin-of-eyeless (toy), eye absent (eya), teashirt (tsh) and sine oculis (So). In Drosophila, mutations of the RDGN leads to failure of eye formation, whereas, forced expression induces ectopic eye formation. EYA functions as a transcriptional co-activator being recruited in the context of local chromatin, but lacking intrinsic DNA binding activity. EYA family members EYA 1–4 are defined by a 275 amino acid carboxyl-terminal motif that is conserved between species, referred to as the EYA domain (ED). The human homologs EYA 1–4 are highly conserved in their EYA domain and amino termini, with the exception of a small tyrosine rich residue region named EYA domain II (3).

Altered expression or functional activity of the RDGN has been documented in a variety of malignancies. DACH1 expression is reduced in breast, prostate, endometrial and brain cancer (4–6). EYA2 is up regulated in ovarian cancer, promoting tumor growth (7). EYA1 and EYA2 enhanced survival in response to DNA damage producing agents in HEK293 cells (8). Eya2 was required for Six1/TGFβ signals that govern a prometastatic phenotype and epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) (9). Although EYA proteins are expressed in human breast cancer, the relationship to molecular genetic subtype, prognosis and the molecular mechanisms governing contact-independent growth are not known.

Previous studies have demonstrated functional interactions between the RDGN and cell-cycle control proteins (2, 6). The DACH1 protein inhibits breast cancer cellular metastasis via the transcriptional repression of IL-8 (10). Breast tumor initiating cells (BTIC) are inhibited by endogenous DACH1 expression through binding to the promoter-regulatory regions of the Nanog and SOX2 genes (11). DACH1 was also shown to inhibit breast cancer cell proliferation via repression of cyclin D1 (6). The cyclin D1 gene encodes the regulatory subunit of a holoenzyme that phosphorylates and inactivates the pRb protein, thereby promoting the DNA synthetic phase of the cell-cycle. The maintenance of HER2 positive breast cancer tumor growth by HER2 positive cells requires cyclin D1 (12).

The current studies were conducted to determine the molecular mechanisms by which EYA1 promotes breast tumor cellular growth. Herein, EYA1 expression in 2,154 breast cancer samples, showed enrichment with cyclin D1 in luminal B breast cancer expression. EYA1 induced contact-independent growth of breast cancer cell lines requiring its phosphatase function. EYA1 induced cyclin D1 expression via its phosphatase function and was recruited to the cyclin D1 promoter AP-1 site. The EYA1 phosphatase function determined the induction of cyclin D1 transcription and local histone acetylation and co-activator recruitment at the cyclin D1 promoter regulatory region.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK 293T) and breast cancer cell lines were maintained in SKBR3 (McCoy’s 5A), BT-474 and T47D (RPMI1640), and MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-453, HBL100, HS578T, and MCF-7 (DMEM) containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin and supplemented with 10% FBS.

Plasmids and shRNA

The mouse cDNA of EYA1 WT and EYA1 D327A phosphatase (EYA1 D327A) mutant, were cloned into the p3×FLAG-CMV-10 (Sigma-Aldrich) vector for transient transfection assays and into the pCDF lentivirus expression vector to establish stable cell lines. The human cyclin D1 promotor luciferase reporter was previously described (13). The shRNAs for EYA1 were purchased from Open biosystem, using the targeted sequences CCCACAAAGAATATAGATGAT and CGACGGGTCTTTAAACAATTT.

Transfections, Gene Reporter Assays and EYA1 Stable Cell Lines

DNA transfection and luciferase assays were performed as previously described. Briefly, cells were seeded at 25% confluence in 24-well plates the day before transfection. Cells were transiently transfected with the appropriate combination of the reporter (0.5 μg per well), expression vectors (calculated as molar concentration equal to 300 ng of control vector), and control vector (300 ng per well) via calcium phosphate precipitation for HEK293T or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for the remaining cell lines, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty four hours after the transfection, luciferase assays were performed at room temperature using an Autolumat LB 953 (EG&G Berthold) as previously described. Lentiviruses were prepared by transient co-transfections of plasmid DNA expressing EYA1 or EYA1 D327A or the vector and packaging plasmids using calcium phosphate precipitation. The Lentiviral supernatants were harvested 48 hours after transfection and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter. Human breast cancer cell line cells were incubated with the lentiviral supernatants in the presence of 8 mg/ml polybrene for 24 hours, cultured for a further 48 hours and subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (FACStar Plus; BD Biosciences) to select for cells expressing GFP. GFP-positive cells were used for subsequent analysis. The cyclin D1 promoter mutant luciferase reporter genes were previously described (14). The cyclin D1 AP-1 site at −953 TGACTCAT TTT was mutated to TGgCgCAT TTT.

Western Blot

For Western blot analyses, cells were pelleted and lysed in buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X100) supplemented with a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics). Antibodies used for immunoprecipitation and Western blot are as follows: anti-FLAG (M2 clone, Sigma), anti-EYA1 (ab85009, Abcam), and antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology were cyclin D1(sc-20044), cyclin E1 (sc-481), CDC25B (sc-5619), β-catenin (sc-7963), p27 (sc-7767), β -actin (sc-47778) and β-tubulin (sc-9104). For cyclin D1 degradation assays, EYA1 wt or mutant stable cell lines (SKBR3 or MDA-MB-453) were treated with 50 ug/ml cycloheximide (CHX) and total protein was collected at sequential time points (15, 30, 60, 90, 120 minutes) for Western blot analysis.

ChIP Assay

ChIP analysis was performed following a previously described protocol (15). MDA-MB-453 cells stably expressing 3xFLAG-EYA1 or EYA1 D327A or control vector were prepared using a ChIP assay kit (Upstate Chemicon) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Chromatin solutions were precipitated overnight with agitation at 4°C using 30 μL of agars with specific antibodies. For a negative control, mouse IgG was immunoprecipitated by incubating the supernatant fraction for 1 h at 4°C with rotation. Precipitated DNAs were analyzed by PCR. The human cyclin D1 promoter specific primers used were as follows: AP-1 site: 5′-GGCAGAGGGGACTAATATTTCCAGCA-3′ and 5′-GAATGGAAAGCTGAGAAACAGTGATCTCC-3′. Primers as negative control site were 5′-TTTCGGAAGCGTTTTCCC-3′and 5′-AGCGCGTTCATTCAGGAA-3′. Antibodies used for IP were: anti-FLAG (M2 clone, Sigma), anti-CBP (sc-369, Santa Cruz), anti-acetyl Histone H3K9 (07–352, Millipore), and anti-Pol II (sc-9001, Santa Cruz).

RT-PCR and Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was prepared using TriZol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Five micrograms of total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA using the SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen). A 25 μL volume reaction consisted of 1 μL reverse transcription product and 10 pM of each primer. The primers used for RT-PCR of the EYA1 which are isoform specific corresponding to exon 9–11 (16) were: 5′-GTTCATCTGGGACTTGGA -3′ and 5′-GCTTAGGTCCTGTCCGTT -3′, primers for cyclin D1 were: 5′-GTGCTGCGAAGTGGAAACC -3′ and 5′-ATCCAGGTGGCGACGATCT-3′, primers for GAPDH: 5′-ATCTTCCAGGAGCGAGACCCC-3′ and 5′-TCCACAATGCCAAAGTTGTCATGG-3′.

Mammosphere Formation and Animal Studies

Mammosphere formation assays were conducted as described previously (17). 5–6 weeks female NOD-SCID mice were purchased from NCI-Frederick and maintained in the transgenic mouse facility. 10 mice in each group were subcutaneously injected with 3 × 106 MDA-MB-453 cells in 0.1 ml PBS with 10% matrigel. Tumor size was monitored twice a week for 8 weeks and tumor weight was measured at the end of the experiment.

Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis Assays

For the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT) assay, cells infected with PCDF, PCDF-Flag-EYA1, or PCDF-Flag-EYA1 D327A were seeded into 96-well plates in normal growth medium, and cell growth was measured every day by MTT assay. To measure the growth curve, cells were seeded into 12-well plates and serially counted for 6 to 7 days. Tritiated thymidine incorporation was conducted as previously described as an assay of cell proliferation (6). For BrdU staining, cells were labeled with 100 uM BrdU for 1 hour in regular culture medium, then washed 3 times with PBS, fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde/PBS for 10 minutes, treated with 4N HCL/1% Triton-X100 for 10 minutes, washed 3 times with 0.1% NP-40/PBS; incubated with mouse anti-BrdU (B8434, Sigma) at 1:1000 for 2 hours at RT and stained with goat anti-mouse AlexaFluor 568 at 1:1000 after washing. 10,000 cells were analyzed by BD FACScan. Apoptotic cells were measured using BD Pharmingen PE Annexin V apoptosis Kit following standard protocol.

Colony Formation Assay

For contact-independent growth (soft agar), cells (4.0 × 103) were plated in triplicate in 2 ml of 0.3% agarose (sea plaque) in complete growth medium overlaid on a 0.5% agarose base, also in complete growth medium. Two weeks after incubation, colonies >50 μm in diameter were counted using an Omnicom 3600 image analysis system. For contact-dependent growth, 2.0 × 103 cells were plated in 6-well plates in triplicate in 2 ml of complete growth medium for 2 weeks. The medium was changed every 4 days. The colonies were visualized after staining with 0.04% crystal violet in methanol for 1–2 h.

Analysis of Public Breast Cancer Microarray Datasets

A breast cancer microarray dataset that was previously compiled from the public repositories Gene Expression Omnibus and ArrayExpress was used to evaluate co-expression of cyclin D1 and EYA1. This microarray dataset includes 102 healthy breast and 2152 breast tumor samples, and tumor samples were classified into five molecular subtypes as previously described (15, 18).

The relationship between CCND1 and EYA1 was explored within each of the five subtypes by comparing EYA1 expression against CCND1 RNA expression using 2D-scatter plots with four quadrants. EYA1 expression was centered around its median expression in healthy breast, while CCND1 expression was centered around its median expression across all breast samples. Within each subtype, the distribution of samples among the four quadrants around x=0 and y=0 was quantified and significance was assessed using a chi-square test. Kaplan-Meier curves and the Log-rank test p-value were used to evaluate survival differences for co-expression profiles among the four quadrants.

Results

Endogenous EYA maintains Cyclin D1 Levels in Breast Cancer Cells

The molecular genetic subtypes of human breast cancer cell lines also include Luminal A, Luminal B, Basal, ErbB2 and claudin-low (19, 20). In order to determine the relative abundance of EYA1 in breast cancer cell lines, a series of breast cancer cell lines including representative examples of these subtypes were examined. qRT-PCR primers were deployed that are specific for the EYA1 isoform. The relative abundance of EYA1 compared with the loading control GAPDH was higher in claudin-low (MDA-MB-231 and HS578T), luminal B (BT-474) and ErbB2 positive (MDA-MB-453 and SKBR3) cells (Fig. 1A). The gene expression profile of the MDA-MB-231 cells are considered a claudin-low subtype, the MDA-MB-453 and SKBR3 as a Her2 subtype and BT-474 are considered luminal B subtype in expression profile (20, 21). Western blot analysis demonstrated similar trends in protein relative abundance as found with the mRNA level in each cell line (insert, Fig. 1A) (Supplemental Fig. 1).

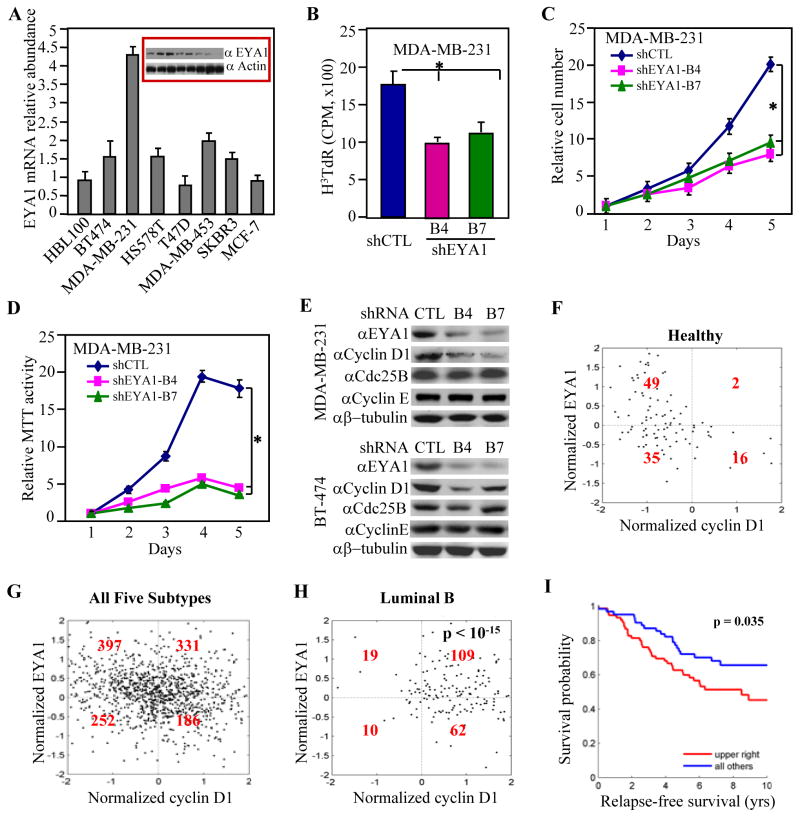

Figure 1. Endogenous EYA maintains breast tumor cellular growth and cyclin D1 abundance.

A) qRT-PCR analysis for EYA1 mRNA levels normalized to GAPDH in a series of breast cancer cell lines. Inset is a corresponding Western blot of the breast cancer cell lines, with the protein loading control β-actin. B) Tritiated thymidine incorporation of EYA1 shRNA transduced MDA-MB-231 cells with data shown as mean ±SEM of 3 separate experiments. C) Cellular proliferation assays of MDA-MB-231 cell transduced with two distinct shRNAs to EYA1, demonstrate either cell number or D) MTT activity, with the data shown as mean ±SEM for N equals 5 separate experiments. E) MDA-MB-231 and BT-474 cells transduced with EYA1 shRNA, were subjected to Western blot analysis for the relative abundance of cell cycle control proteins using antibodies as indicated. F) Normalized expression of EYA1 and cyclin D1 in 102 healthy breast tissues. G) Relative expression of EYA1 and cyclin D1 in all five type breast cancer or (H) Luminal B subtype. I) Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis comparing high cyclin D1/high EYA1 (upper right) with all other breast cancers. Outcome by relapse free survival is worse for high EYA1/high cyclin D1 breast cancers.

The increased abundance of EYA1 in MDA-MB-231 cells provided an opportunity to determine the function of EYA1 using shRNA. DNA synthesis evaluated by tritiated thymidine incorporation was reduced 40% using two separate shRNA (Fig. 1B). Cellular proliferation, assessed by either cell counting, or MTT activity, was reduced ~80% (Fig. 1C, D). We examined the role of endogenous EYA1 in maintaining the abundance of endogenous cell cycle related protein expression. EYA1 shRNA reduced EYA1 abundance ~90%, without altering the cyclin E levels in both MDA-MB-231 and BT-474 (Fig. 1E). CDC25B abundance was reduced ~25%. However, cyclin D1 abundance was reduced by ~70% (Fig. 1E). EYA1 shRNA reduced EYA1 and cyclin D1 mRNA levels ~90% (supplemental Fig. 2). The reduction in cyclin D1 abundance and subsequent reduction in cell proliferation is in agreement with the previous report that the G1/S cell cycle transition and proliferation of human breast cancer cells is dependent upon the abundance of cyclin D1 (22). To analyze the co-expression of cyclin D1 and EYA1 in human breast cancer, we used a collection of 2152 breast tumor samples (15). We stratified the samples into five molecular subtypes, including Luminal A, Luminal B, Basal, Normal-like, and Her2-overexpressing. Compared with normal breast tissue (Fig. 1F) and all breast cancers (Fig. 1G), significant enrichment for cyclin D1 and EYA1 co-expression was identified in the luminal B subtype (P < 1 × 10−15; Fig. 1H). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that co-expression of cyclin D1 and EYA1 have a negative impact on recurrence-free survival time (p = 0.035; Fig. 1I). There was no significant independent relapse-free survival significance of either Cyclin D1 or EYA1 alone in luminal B breast cancer patients.

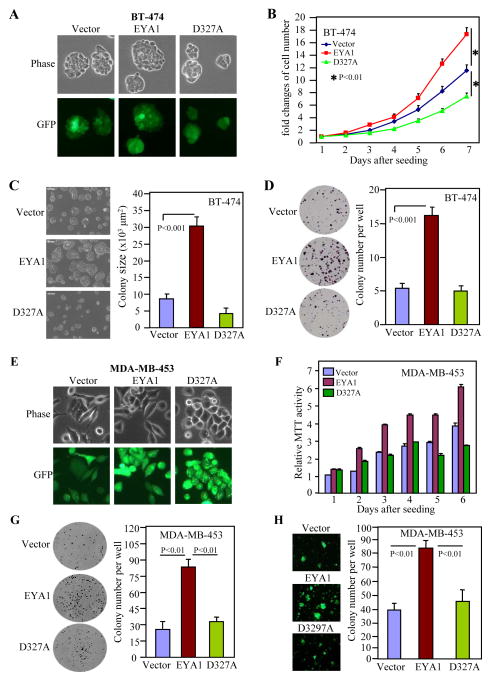

The EYA1 phosphatase domain is required for the induction of breast cancer cell contact-independent growth

In order to examine further the functional significance of EYA1 in breast cancer cellular proliferation, the human BT-474, MDA-MB-453 and SKBR3 breast cancer cell lines were transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding either EYA1 or a phosphatase-defective mutant (EYA1 D327A). Lentiviral transduction of the BT-474 cells with the expression vector resulted in green fluorescence of the transduced cells (Fig. 2A). Cellular proliferation assessed by cell counting showed a 40% increase in proliferation by EYA1 (Fig. 2B). No proliferative advantage was observed in phosphatase defective EYA1 D327A transduced cells, which reduced cell number compared to vector control (Fig. 2B). Colony formation assays in contact-dependent growth demonstrated a 3-fold increase in the number of colonies that was dependent upon the EYA1 phosphatase activity (Fig. 2C). Contact independent growth in soft agar showed a similar 3-fold induction in colony number by EYA1 that was dependent on the phosphatase domain (Fig. 2D). The human MDA-MB-453 breast cancer cell line showed a similar increase in proliferation assessed by MTT assay and increase in colony formation in the presence of EYA1 that was reduced by mutation of the EYA1 phosphatase domain (Fig. 2E–H). In addition, phosphatase-dependent stimulation of cellular growth and colony formation was also observed in the SKBR3 breast cancer cell line (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 2. The phosphatase function of EYA1 is required for the induction of contact-independent breast tumor growth.

BT-474 cells transduced with an expression vector encoding either EYA1 or a phosphatase dead mutant (EYA1 D327A) with an IRES-GFP were assessed by phase contrast microscopy or B) cellular proliferation by counting, C) growth in soft agar or D) colony formation assays of contact-dependent growth in tissue culture where the data shown is colony number per well, as mean ±SEM for five separate experiments. MDA-MB-453 cells expressing EYA1 or EYA1 D327A were assessed by E) phase contrast microscopy, F) cell proliferation using the MTT assay, G) colony number in contact-dependent culture or H) the number of colonies in soft agar. The data are shown as mean ±SEM for five separate experiments.

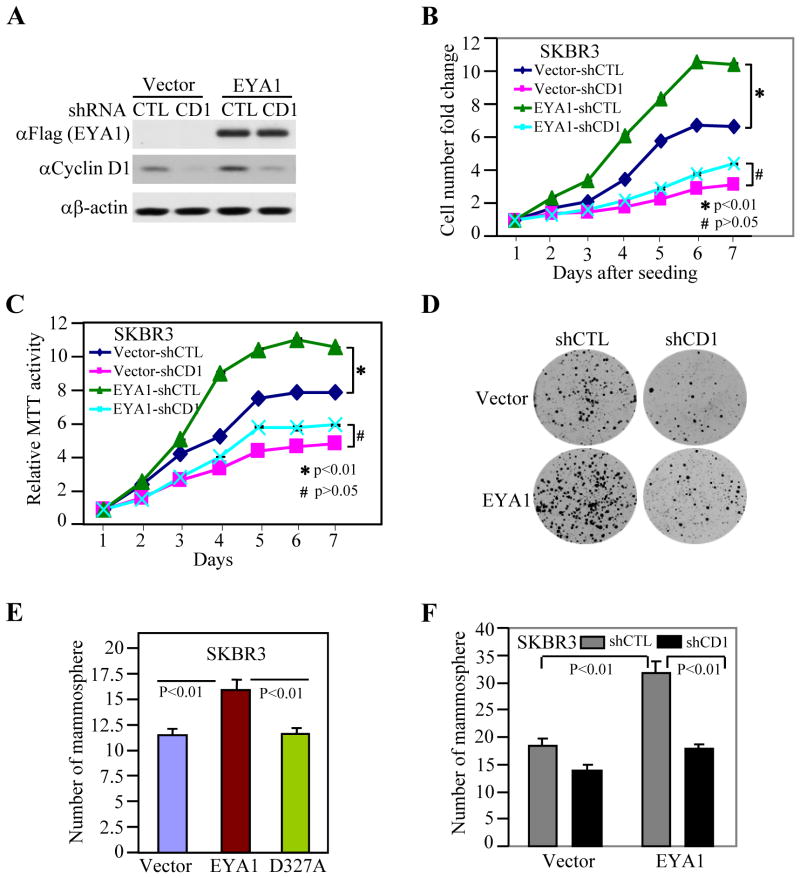

Cyclin D1 is required by EYA1-induced breast tumor colony formation, cellular proliferation and mammosphere formation

In order to determine whether cyclin D1 was required for proliferation induced by EYA1, cells were transduced with the EYA1 expression vector and shRNA to cyclin D1, or a control shRNA. Cyclin D1 levels were reduced by cyclin D1 shRNA (Fig. 3A), associated with a reduction in EYA1-dependent cellular proliferation from 10-to 4-fold (Fig. 3B, C). In addition, the EYA1-mediated induction of colony formation was abrogated by cyclin D1 shRNA (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. EYA1-dependent induction of breast cancer cell proliferation and mammosphere formation is cyclin D1-dependent.

A) Western blot of SKBR3 cells transduced with either on EYA1 expression vector and/or shRNA to cyclin D1. Antibodies were directed either to the FLAG epitope of EYA1 or to endogenous cyclin D1. B) Cellular proliferation determined by cell counting of SKBR3 cells expressing EYA1, with or without, shRNA to cyclin D1. Analysis was also conducted by C) MTT assay as a surrogate measure of cellular proliferation or D) colony formation assays. E) Mammosphere assays were conducted with cells transduced with either EYA1 or the EYA1 D327A. The numbers of mammospheres are shown. F) Cells transduced with shRNA to cyclin D1 demonstrate a reduction in the number of mammospheres in EYA1 overexpressing cells.

As SKBR3 colony number and size were increased by EYA1, we considered the possibility that EYA1 may contribute to enhancing BTIC. As a surrogate of BTIC, we conducted mammosphere assays as previously described (10, 23), assessing the number and size of the mammospheres. Expression of EYA1 enhanced mammosphere number, which was abrogated by mutation of the EYA1 phosphatase domain (Fig. 3E). Cyclin D1 shRNA reduced the number of mammospheres formed in the basal state (Fig. 3F), and completely abrogated EYA1-mediated induction of mammosphere formation (Fig. 3F).

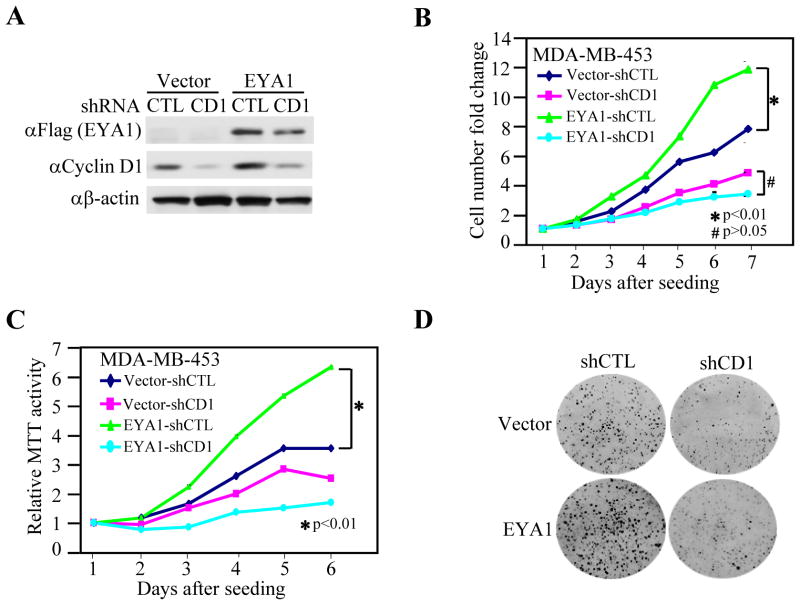

In MDA-MB-453 cells, cyclin D1 shRNA reduced cyclin D1 abundance induced by EYA1 (Fig. 4A) and reduced cellular proliferation as assessed by growth curve, MTT assay or colony formation assays (Fig. 4B–D).

Figure 4. EYA induced MDA-MB-453 cell growth is cyclin D1-dependent.

A Western blot of MDA-MB-453 cells overexpressing EYA1 with either control or cyclin D1 shRNA. B) Cellular growth assays determined by cellular counting or by C) MTT assay. D) Representative examples of MDA-MB-453 colony formation in cells stably expressing EYA1 with either control or shCyclin D1.

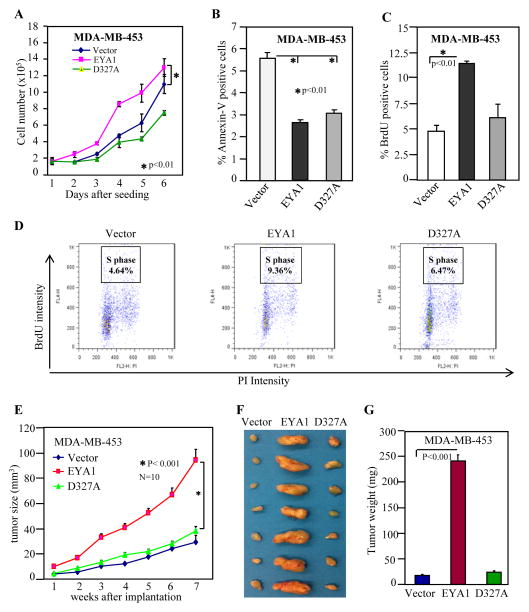

EYA1 Induced DNA Synthesis But Not Apoptosis, is Dependent Upon the EYA1 Phosphatase Domain Determined Growth Ability

Cell growth, evaluated by counting cell number daily, demonstrated EYA1 enhanced proliferation. The EYA1 phosphatase defective mutant failed to induce cell proliferation and showed reduced cell proliferation (Fig. 5A). To further distinguish the effect of EYA1 on apoptosis and proliferation, Annexin V staining and BrdU incorporation were performed. Both EYA1 wt and the phosphatase mutant significantly inhibited apoptosis (Fig. 5B); however, stimulation of DNA synthesis by EYA1 depended on its phosphatase activity (Fig. 5C, D). To measure the in vivo growth promoting function of EYA1, MDA-MB-453 cells stably expressing EYA1 were injected subcutaneously into immune-deficient mouse. MDA-MB-453 tumor growth was dramatically increased by EYA1 as determined by tumor volume (Fig. 5E) and tumor weight (Fig. 5 F, G). The stable expression of the EYA1 phosphatase defective mutant showed reduced cell growth in vivo by volume and tumor weight (Fig. 5E, F).

Figure 5. Enhanced DNA synthesis and tumor growth depend upon the phosphatase domain.

A) A growth curve of MDA-MB-453 cells expressing either EYA1 or the phosphatase mutant D327A shown as days after plating with B) percentage of cells positive for Annexin V or C) BrdU staining shown as mean ±SEM. D) Example of FACS illustrating the proportion of cells in the S-phase. Comparison is shown of cells expressing EYA1 of the EYA1 D327A mutant. E) The size of the breast tumors in nude mice with F) examples of extirpated tumors comparing vector vs. EYA1 or EYA1 D327A expression vector. G) Tumor weight shown as mean ±SEM for N = 10 separate tumors for each genotype (vector, EYA1, EYA1 D237A).

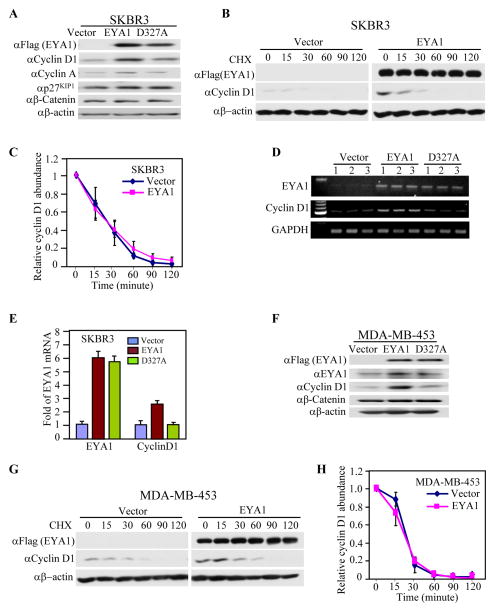

EYA1 Induction of Cyclin D1 Requires The Eya Phosphatase Activity

Given the requirement for cyclin D1 in EYA1-mediated growth, we determined the mechanism by which EYA1 induced cyclin D1 abundance. Western blot analysis was conducted. The amino terminal epitope of the EYA1 protein (Fig. 6A) was recognized by the FLAG antibody, showing similar levels of expression for EYA1 and EYA1 D327A (Fig. 6A). The relative abundance of cyclin D1 was induced 5-fold by EYA1, which was reduced (60%) by mutation of the phosphatase domain after normalization for the relative abundance of EYA1 protein by Western blot. The relative abundance of cyclin D1 was induced without changes in the relative abundance of cyclin A, p27KIP1 or β-catenin protein (Fig. 6A). In order to determine the mechanisms by which EYA1 induced cyclin D1 abundance, analysis was conducted of cyclin D1 protein levels in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (Fig. 6B). Confirmed by quantitative analysis of multiple experiments, no significant change in the relative abundance of cyclin D1 mRNA stability occurred when EYA1 and the control empty vector were compared (Fig. 6C). Cyclin D1 mRNA abundance determined by quantitative RT-PCR was increased 5-fold by EYA1 (Fig. 6D). The induction of cyclin D1 mRNA by EYA1 was dependent upon the EYA1 phosphatase function (Fig. 6E). Similar results were observed in MDA-MB-453 cells (Fig. 6F–H).

Figure 6. EYA1 induces cyclin D1 protein and mRNA abundance.

A) Western blot of SKBR3 cells transduced with vectors encoding either EYA1 or EYA1 D327A. B) Western blot of EYA or vector control SKBR3 cells treated with cycloheximide showing cyclin D1 abundance is increased by EYA1. C) Changes in cyclin D1 protein levels after cycloheximide treatment. Data are mean ±SEM of N=3. D) mRNA levels of EYA1 or cyclin D1 determined by QT-PCR in SKBR3 stable lines. E) Quantization of mRNA shown as mean ±SEM of N = 3 separate experiments). F) Western blot of MDA-MB-453 cells expressing either EYA1 or EYA1 D327A, shows the induction of cyclin D1 abundance is dependent upon the EYA phosphatase domain. G) Cyclin D1 protein levels upon cycloheximide treatment with the quantization shown in H) as mean ± SEM of N > 3 separate experiments.

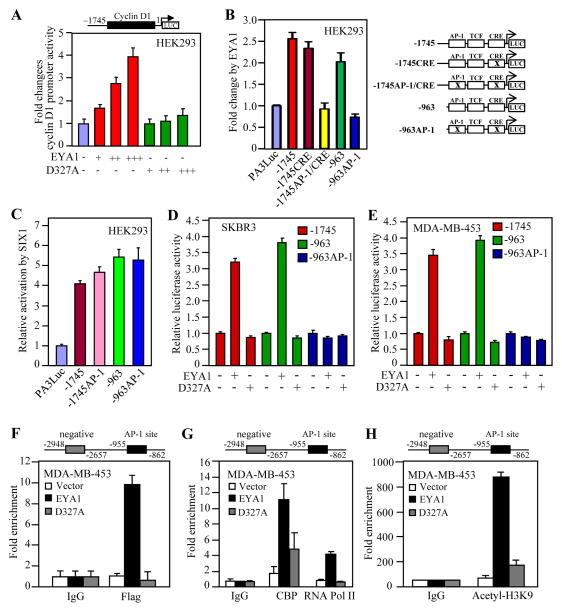

EYA1 Induces the Cyclin D1 Promoter via the AP-1 site at −953, Recruiting Co-integrators in a Phosphatase-Dependent Manner

In order to determine whether EYA1 directly activated the cyclin D1 promoter, luciferase reporter assays were conducted (Fig. 7A). The cyclin D1 promoter was induced 4-fold by EYA1 in a phosphatase-dependent manner. Point mutation of the AP-1 site at −953 reduced EYA1-dependent induction (Fig. 7B). In Drosophila, eya and so form part of a common signaling pathway. Six1 is known to induce the cyclin D1 promoter (28). In order to determine whether SIX1 regulates the cyclin D1 promoter through the EYA1 cis-response element, co-transfection experiments were conducted in several cell types (Fig. 7C–E). In HEK293 cells, SIX1 induced the cyclin D1 promoter; however, mutation of the EYA1-responsive AP-1 site at −953 did not affect SIX1-dependent activation (Fig. 7C). Phosphatase dependent activation of the cyclin D1 promoter by EYA1 at the AP-1 site were also observed in SKBR3 and MDA-MB-453 cell lines (Fig. 7D, E). This finding indicates that EYA1 and SIX1 regulate the cyclin D1 promoter through distinct elements. These findings do not however exclude a potential role for Six1 in EYA1-dependent induction of cellular proliferation. Chromatin Immuno-Precipitation assays (ChIP) demonstrated the recruitment of EYA1 to the CRE/AP-1 site of the cyclin D1 promoter at −953. Recruitment of EYA1 occurred in a phosphatase-dependent manner (Fig. 7F). In contrast, there was no recruitment of EYA1 to negative control sequences located at −1500 (data not shown). Next, we examined the potential role of EYA1 in regulating the recruitment of transcriptional co-regulators in the context of local chromatin. Expression of EYA1 enhanced the recruitment of CBP and RNA polymerase II (Fig. 7G), and increased the acetylation of Histone3 [H3K9] (Fig. 7H), consistent with transcriptionally active chromatin (Fig. 7G).

Figure 7. EYA1 induction of cyclin D1 promoter activity via the AP-1 site requires the EYA1 phosphatase function.

A) Cyclin D1 promoter reporter activity in cells transfected with either EYA1 or the EYA1 D327A mutant with B) relative induction of the mutant reporters shown as mean ±SEM of N > 5 separate experiments. (C-E) Luciferase reporter assays of cyclin D1 promoter fragments, assessed in the presence of co-transfected expression vectors for SIX1 in HEK293, (C) for EYA1 or EYA1 D327A in SKBR3 (D) and MDA-MB-453 (E). The data are mean ± SEM of N=5 separate transfection. (F–H) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIP) of MDA-MB-453 cells transduced with either EYA1 or EYA1 D327A. Recruitment of EYA1 (FLAG), CBP, RNA polymerase II, or acetyl-H3K9 is shown as mean ±SEM for 3 separate experiments. The -fold change in recruitment of proteins to the cyclin D1 AP-1 site is shown.

DISCUSSION

The current studies demonstrate that EYA1 enhances breast cancer cellular proliferation both in tissue culture and in vivo. EYA1 enhanced growth via increased cellular proliferation and DNA synthesis. The induction of cellular proliferation by EYA1 in BT-474, SKBR3 and MDA-MB-453 cells was dependent upon the phosphatase function and the induction of breast tumor growth in vivo required the phosphatase domain. EYA1 also reduced apoptosis as determined by Annexin V positive cells; however the inhibition of apoptosis by EYA1 was independent of the phosphatase domain. These findings suggest EYA1 promotes breast tumor growth through both phosphatase-dependent and phosphatase-independent mechanisms. These studies contrast with the findings in the developing kidney of Eya−/− mouse embryos in which increased apoptosis correlated with increased H2AX Ser139 phosphorylation (8). Tyrosine dephosphorylation of H2AX is thought to modulate apoptosis, through dephosphorylation of an H2AX carboxyl-terminal tyrosine phosphate (Y142), under hypoxic conditions or under circumstances of DNA damage. The EYA1 effect was dependent upon increased ATM/ATR activity. It is likely that the ability of the EYA1 phosphatase function to regulate apoptosis may depend upon the ATM/ATR activity and relative tumor hypoxia.

In order to determine the mechanism by which EYA1 enhanced breast cancer cellular proliferation, we considered the cyclin genes as potential targets of EYA1-induced breast tumor cellular proliferation. We considered targets of the cell cycle, in which the induction of the gene expression was dependent upon the EYA1 phosphatase domain. The abundance of cyclin D1, but not cyclin E or CBC25A, was induced by EYA1, suggesting cyclin D1 was a target of EYA1 induced cellular proliferation. Cyclin D1 shRNA demonstrated the requirement for cyclin D1 in EYA1-dependent breast cancer cellular proliferation. These findings are consistent with evidence that cyclin D1 anti-sense reduces ErbB2-induced mammary tumorigenesis in mice (24) and findings that breast tumor progression of MMTV-Ras or MMTV-ErbB2 transgenics is reduced in cyclin D1−/− mice (25). Cyclin D1 however is not required for the induction of mammary tumors induced by either the activated β-catenin or c-Myc oncogenic pathways in vivo (25, 26), demonstrating oncogene-specific roles for cyclin D1 in mammary tumorigenesis. The current studies extend our understanding of the requirement for cyclin D1 in breast tumor proliferation by demonstrating that cyclin D1 is required for EYA1 induced breast tumor growth. The studies do not exclude the possibility that other genes may be induced by EYA1, which may also contribute to EYA1-induced breast tumor growth. Furthermore, the ability of EYA1 to induce proliferation of breast cancer cells may depend upon the oncogenic drivers or the breast cell lines or tumor. In this regard, the EYA1 phosphatase function was not required for the induction of cell proliferation assessed using the WST assays in MCF-7 cells, a cell type in which the cyclin D1 gene product is overexpressed through amplification (27).

The abundance of cyclin D1 is regulated through distinct mechanisms, including post translational modification by phosphorylation and the induction of mRNA and/or gene transcription. In the current studies EYA1 induced cyclin D1 mRNA transcription, as demonstrated by cycloheximide mRNA stability studies. The induction of cyclin D1 mRNA and promotor activity by EYA1 was dependent upon the EYA1 phosphatase function. Mutational analysis demonstrated a requirement for the AP-1/CRE transcription-factor binding sites and point mutation at the AP-1 site abrogated EYA1 induced transcriptional induction of the cyclin D1 promotor. The mutation of the AP-1 site of the cyclin D1 promotor −953, does not affect the SIX1 binding sites, located 3′ at −919 and −614 of the murine cyclin D1 promoter (28) and did not affect transactivation by SIX1 expression in reporter genes assays (Fig. 7C). These findings suggest the SIX1 and EYA1 components of the RDGN function to induce a common gene target through distinct cis elements. Using c-fos−/−/fos B−/−, the AP-1 site was shown to serve as a site of convergence between serum stimulation and cell-cycle progression (29) and the AP-1 site was previously identified as a key site involved in the gene induction of cyclin D1 expression by oncogenic Ras (14).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays demonstrated the recruitment of EYA1 to the cyclin D1 AP-1 site and no recruitment of EYA1 to distinct cyclin D1 sequences unrelated to the AP-1 site. The combinational patterns of histone modification at active genes are complex (30), however we chose H3K9 acetylation (H3K9), as regions enriched with H3 acetylation are often found to be enhancers (31). Measurements of transcriptionally active chromatin, in particular acetylated H3K9, demonstrated increased H3K9 acetylation in the presence of EYA1. A significant reduction in recruitment of the phosphatase-defective EYA1 mutant was associated with the reduced recruitment of H3K9 to the cyclin D1 AP-1 site. The defect in recruitment to local chromatin of the EYA1 phosphatase mutant suggests EYA1 dephosphorylation contributes actively to the chromatin interaction. Other phosphatases are known to interact with and regulate local chromatin structures including PP4, PP2A, PP6, Wip1, GLC7 (PP1 homology in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae) and Rep-Man-PP1. Repo-Man-PP1 is a phosphatase complex that regulates histone H3 Thr3, Ser10, Ser28 dephosphorylation which is essential for the reestablishment of heterochromatin in post-mitotic cells (32).

RNA polymerase II (RNA PII) is required for transcription of protein coding genes (33) and reduced recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the site is consistent with the reduced transcriptional activity of the EYA1-D327A mutant. The cyclin D1 AP-1 site is known to recruit the AP-1 transcription factors c-Jun, c-Fos, FRA1, FRA2 (29) and reduced recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the AP-1 site is consistent with a mechanism by which EYA1 determines the induction of cyclin D1 gene expression.

Mammospheres reflect the combination of both symmetrical and asymmetrical divisions (34). The number of mammospheres may serve as a surrogate of breast tumor stem cell expansion (BTSC). The current studies demonstrate that EYA1 enhanced the number of mammospheres formed. Several lines of evidence support the importance of BTSC or tumor initiating cells in the onset and progression of breast cancer (34, 35). Herein, the induction of mammosphere formation by EYA1 was dependent upon the phosphatase domain. The mechanism by which EYA1 promotes BTSC expansion may include the ability of EYA1 to be recruited to AP-1 sites as the AP-1 transcription factor, c-Jun, is known to promote BTSC expansion (17). Alternately, previous studies had identified physical interaction between DACH1 and EYA1. DACH1 is known to occupy the promotors of several stem cell regulatory genes including Sox, Oct, and Nanog (10). The current studies raise the possibility that EYA1 may be recruited by a DACH/EYA1 complex to the genes associated with the induction of tumor initiating cells that may in turn contribute to the progression of tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part, by the National Institutes of Health Grants RO1CA132115, R01CA70896, R01CA75503 and R01CA86072 (R.G.P.) and grant P30CA56036 (Kimmel Cancer Center Core Grant to R.G.P.). This work was also supported by a grant for Dr. Ralph and Marian C. Falk Medical Research Trust (to R.G.P.), Margaret Q. Landenberger Research Foundation (to K.W.), the Department of Defense Concept Award W81XWH-11-1-0303 (K.W.) and support in part from National Natural Science Foundation of China; 81072169 and 81261120395 (K.W.).

Footnotes

For reprints: director@kimmelcancercenter.org or kmwu2005@gmail.com

Conflicts of Interest: R.G.P. holds minor (< $10,000) ownership interests in, and serves as CSO/Founder of the biopharmaceutical companies ProstaGene, LLC and AAA Phoenix, Inc. R.G.P. additionally holds ownership interests (value unknown) for several submitted patent applications.

References

- 1.Voas MG, Rebay I. Signal integration during development: insights from the Drosophila eye. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:162–175. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popov VM, Wu K, Zhou J, Powell MJ, Mardon G, Wang C, Pestell RG. The Dachshund gene in development and hormone-responsive tumorigenesis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silver SJ, Davies EL, Doyon L, Rebay I. Functional dissection of eyes absent reveals new modes of regulation within the retinal determination gene network. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5989–5999. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.17.5989-5999.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popov VM, Zhou J, Shirley LA, Quong J, Yeow WS, Wright JA, Wu K, Rui H, Vadlamudi RK, Jiang J, Kumar R, Wang C, Pestell RG. The cell fate determination factor DACH1 is expressed in estrogen receptor-alpha-positive breast cancer and represses estrogen receptor-alpha signaling. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5752–5760. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu K, Katiyar S, Witkiewicz A, Li A, McCue P, Song LN, Tian L, Jin M, Pestell RG. The cell fate determination factor dachshund inhibits androgen receptor signaling and prostate cancer cellular growth. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3347–3355. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu K, Li A, Rao M, Liu M, Dailey V, Yang Y, Di Vizio D, Wang C, Lisanti MP, Sauter G, Russell RG, Cvekl A, Pestell RG. DACH1 is a cell fate determination factor that inhibits cyclin D1 and breast tumor growth. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:7116–7129. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00268-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L, Yang N, Huang J, Buckanovich RJ, Liang S, Barchetti A, Vezzani C, O’Brien-Jenkins A, Wang J, Ward MR, Courreges MC, Fracchioli S, Medina A, Katsaros D, Weber BL, Coukos G. Transcriptional coactivator Drosophila eyes absent homologue 2 is up-regulated in epithelial ovarian cancer and promotes tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2005;65:925–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook PJ, Ju BG, Telese F, Wang X, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Tyrosine dephosphorylation of H2AX modulates apoptosis and survival decisions. Nature. 2009;458:591–596. doi: 10.1038/nature07849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farabaugh SM, Micalizzi DS, Jedlicka P, Zhao R, Ford HL. Eya2 is required to mediate the pro-metastatic functions of Six1 via the induction of TGF-beta signaling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and cancer stem cell properties. Oncogene. 2011 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu K, Jiao X, Li Z, Katiyar S, Casimiro MC, Yang W, Zhang Q, Willmarth NE, Chepelev I, Crosariol M, Wei Z, Hu J, Zhao K, Pestell RG. Cell fate determination factor Dachshund reprograms breast cancer stem cell function. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:2132–2142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.148395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu K, Katiyar S, Li A, Liu M, Ju X, Popov VM, Jiao X, Lisanti MP, Casola A, Pestell RG. Dachshund inhibits oncogene-induced breast cancer cellular migration and invasion through suppression of interleukin-8. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6924–6929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802085105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee RJ, Albanese C, Fu M, D’Amico M, Lin B, Watanabe G, Haines GK, 3rd, Siegel PM, Hung MC, Yarden Y, Horowitz JM, Muller WJ, Pestell RG. Cyclin D1 is required for transformation by activated Neu and is induced through an E2F-dependent signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:672–683. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.672-683.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albanese C, D’Amico M, Reutens AT, Fu M, Watanabe G, Lee RJ, Kitsis RN, Henglein B, Avantaggiati M, Somasundaram K, Thimmapaya B, Pestell RG. Activation of the cyclin D1 gene by the E1A-associated protein p300 through AP-1 inhibits cellular apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34186–34195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albanese C, Johnson J, Watanabe G, Eklund N, Vu D, Arnold A, Pestell RG. Transforming p21ras mutants and c-Ets-2 activate the cyclin D1 promoter through distinguishable regions. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23589–23597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casimiro MC, Crosariol M, Loro E, Ertel A, Yu Z, Dampier W, Saria EA, Papanikolaou A, Stanek TJ, Li Z, Wang C, Fortina P, Addya S, Tozeren A, Knudsen ES, Arnold A, Pestell RG. ChIP sequencing of cyclin D1 reveals a transcriptional role in chromosomal instability in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:833–843. doi: 10.1172/JCI60256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okada M, Fujimaru R, Morimoto N, Satomura K, Kaku Y, Tsuzuki K, Nozu K, Okuyama T, Iijima K. EYA1 and SIX1 gene mutations in Japanese patients with branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome and related conditions. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:475–481. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiao X, Katiyar S, Willmarth NE, Liu M, Ma X, Flomenberg N, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG. c-Jun induces mammary epithelial cellular invasion and breast cancer stem cell expansion. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8218–8226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.100792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Velasco-Velazquez M, Jiao X, De La Fuente M, Pestell TG, Ertel A, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG. CCR5 antagonist blocks metastasis of basal breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3839–3850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holliday DL, Speirs V. Choosing the right cell line for breast cancer research. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:215. doi: 10.1186/bcr2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollestelle A, Nagel JH, Smid M, Lam S, Elstrodt F, Wasielewski M, Ng SS, French PJ, Peeters JK, Rozendaal MJ, Riaz M, Koopman DG, Ten Hagen TL, de Leeuw BH, Zwarthoff EC, Teunisse A, van der Spek PJ, Klijn JG, Dinjens WN, Ethier SP, Clevers H, Jochemsen AG, den Bakker MA, Foekens JA, Martens JW, Schutte M. Distinct gene mutation profiles among luminal-type and basal-type breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:53–64. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prall OW, Rogan EM, Musgrove EA, Watts CK, Sutherland RL. c-Myc or cyclin D1 mimics estrogen effects on cyclin E-Cdk2 activation and cell cycle reentry. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4499–4508. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, Jackson KW, Clarke MF, Kawamura MJ, Wicha MS. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee RJ, Albanese C, Fu M, D’Amico M, Lin B, Watanabe G, Haines GK, 3rd, Siegel PM, Hung MC, Yarden Y, Horowitz JM, Muller WJ, Pestell RG. Cyclin D1 is required for transformation by activated Neu and is induced through an E2F-dependent signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:672–683. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.672-683.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu Q, Geng Y, Sicinski P. Specific protection against breast cancers by cyclin D1 ablation. Nature. 2001;411:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/35082500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowlands TM, Pechenkina IV, Hatsell SJ, Pestell RG, Cowin P. Dissecting the roles of beta-catenin and cyclin D1 during mammary development and neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11400–11405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1534601100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandey RN, Rani R, Yeo EJ, Spencer M, Hu S, Lang RA, Hegde RS. The Eyes Absent phosphatase-transactivator proteins promote proliferation, transformation, migration, and invasion of tumor cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:3715–3722. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu Y, Davicioni E, Triche TJ, Merlino G. The homeoprotein six1 transcriptionally activates multiple protumorigenic genes but requires ezrin to promote metastasis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1982–1989. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown JR, Nigh E, Lee RJ, Ye H, Thompson MA, Saudou F, Pestell RG, Greenberg ME. Fos family members induce cell cycle entry by activating cyclin D1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5609–5619. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Zang C, Rosenfeld JA, Schones DE, Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Peng W, Zhang MQ, Zhao K. Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2008;40:897–903. doi: 10.1038/ng.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roh TY, Wei G, Farrell CM, Zhao K. Genome-wide prediction of conserved and nonconserved enhancers by histone acetylation patterns. Genome Res. 2007;17:74–81. doi: 10.1101/gr.5767907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vagnarelli P, Earnshaw WC. Repo-Man-PP1: a link between chromatin remodelling and nuclear envelope reassembly. Nucleus. 2012;3:138–142. doi: 10.4161/nucl.19267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadonaga JT. Regulation of RNA polymerase II transcription by sequence-specific DNA binding factors. Cell. 2004;116:247–257. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu Z, Pestell TG, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG. Cancer stem cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:2144–2151. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jamieson CH, Ailles LE, Dylla SJ, Muijtjens M, Jones C, Zehnder JL, Gotlib J, Li K, Manz MG, Keating A, Sawyers CL, Weissman IL. Granulocyte-macrophage progenitors as candidate leukemic stem cells in blast-crisis CML. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:657–667. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.